Venue: Old Fitzroy Theatre (Woolloomooloo NSW), Feb 13 – 28, 2026

Playwright: Jennifer Lunn

Director: Emma Canalese

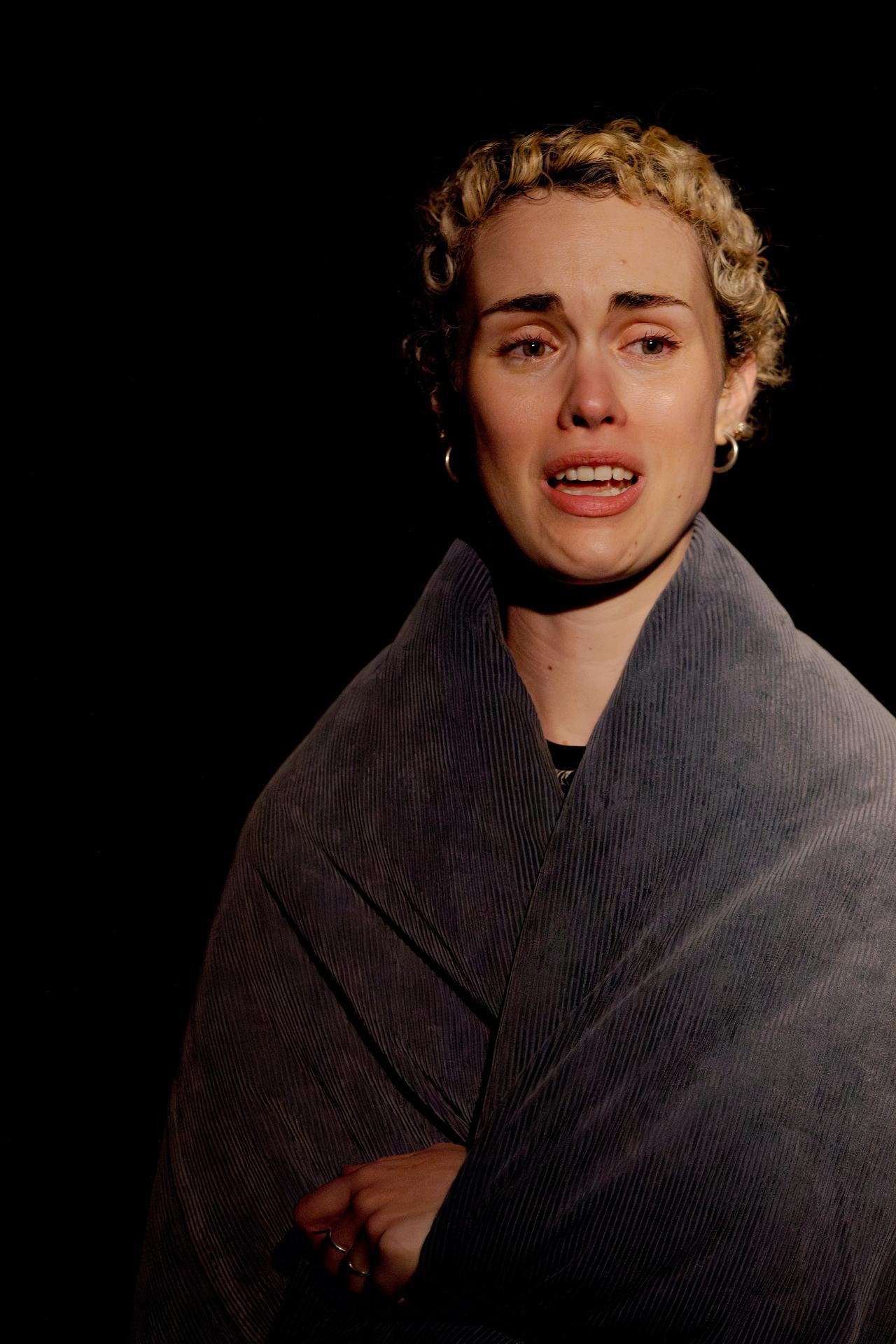

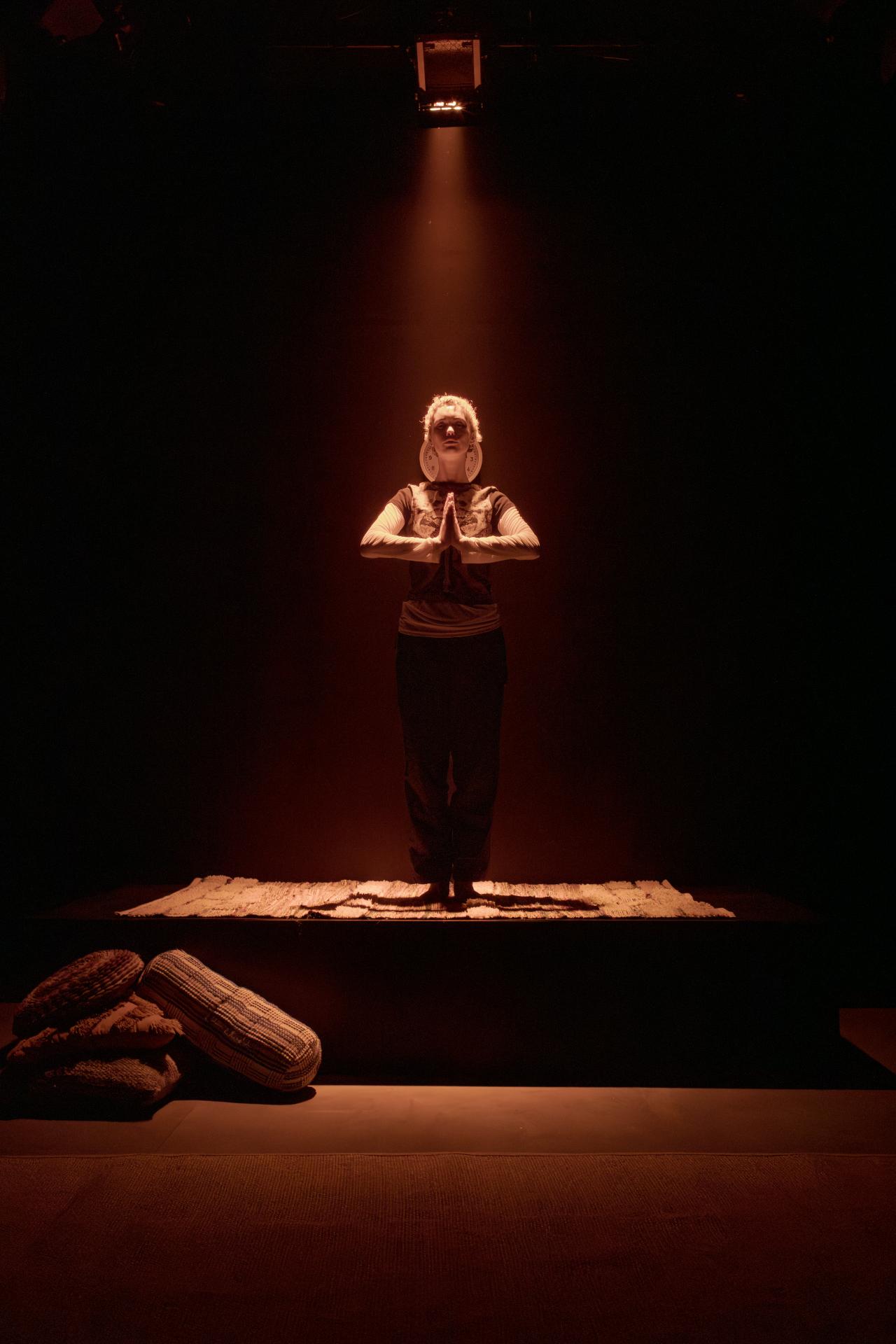

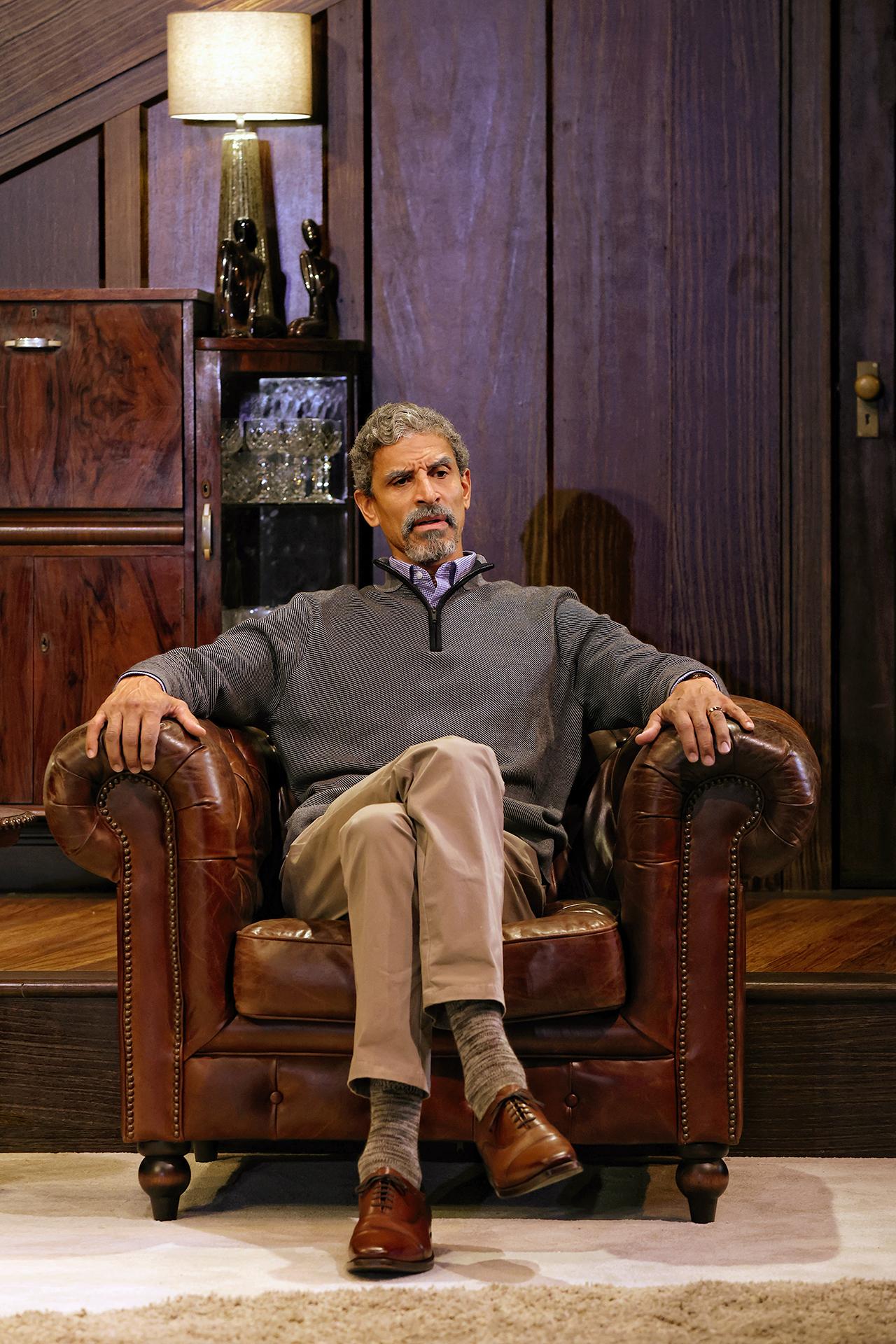

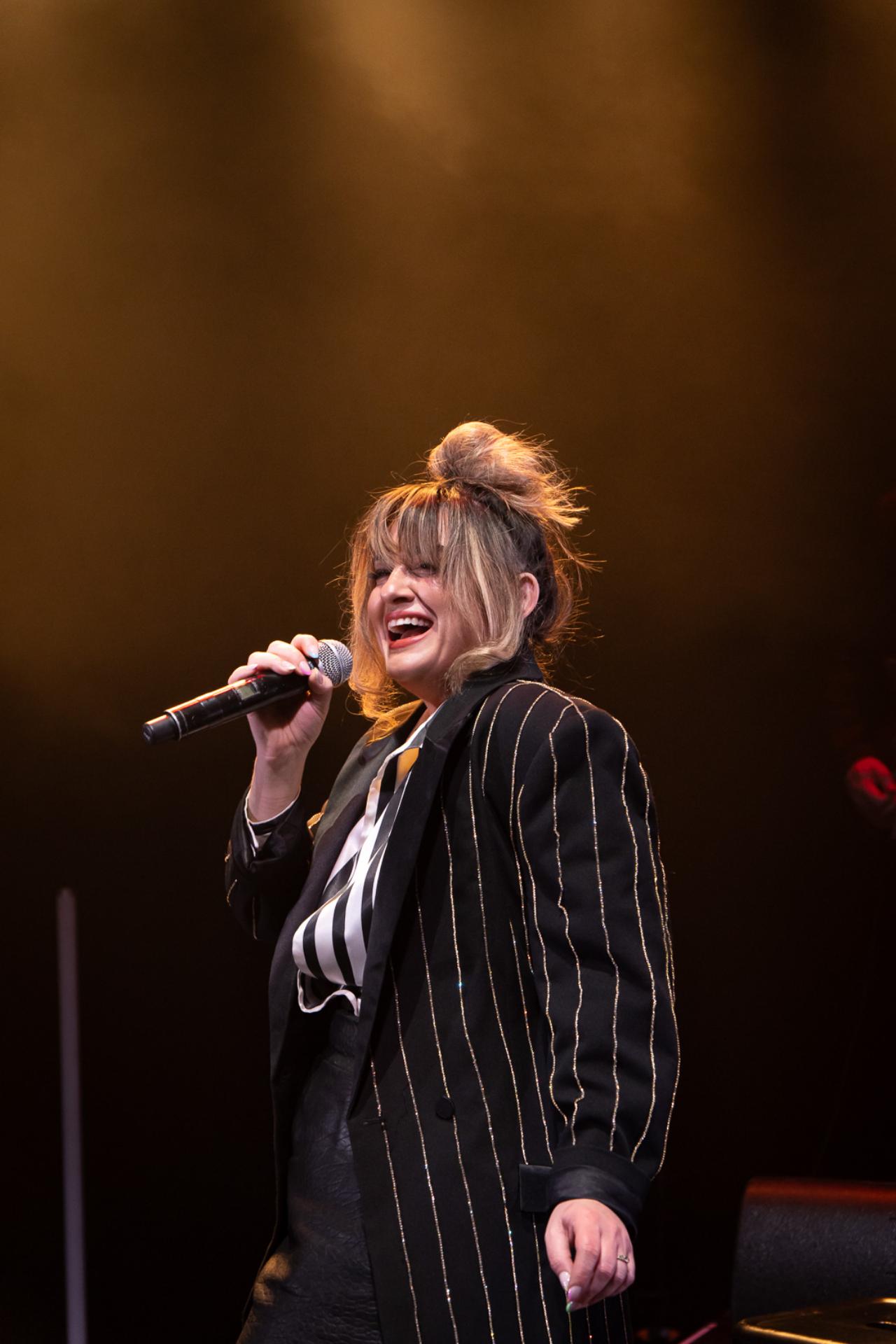

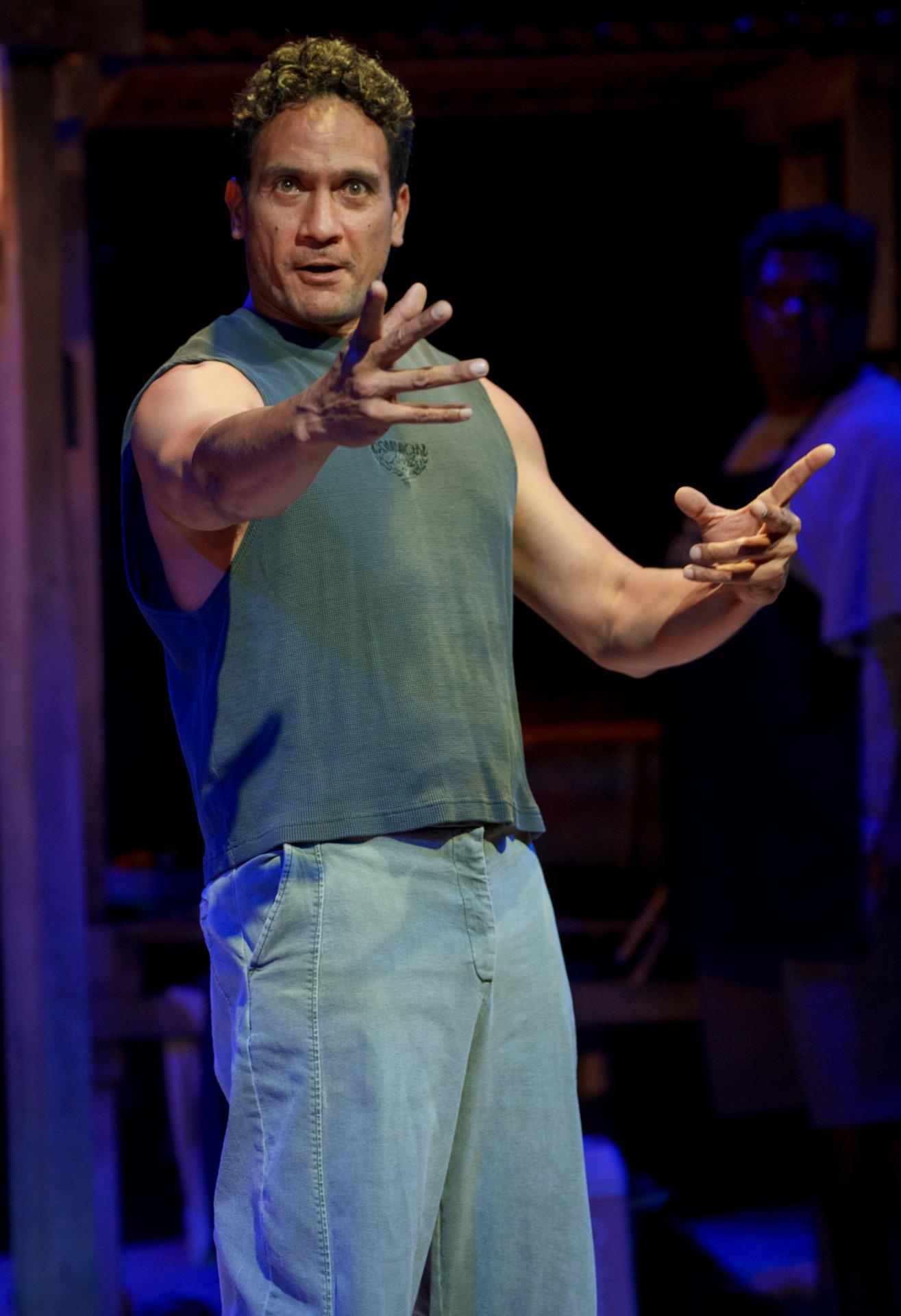

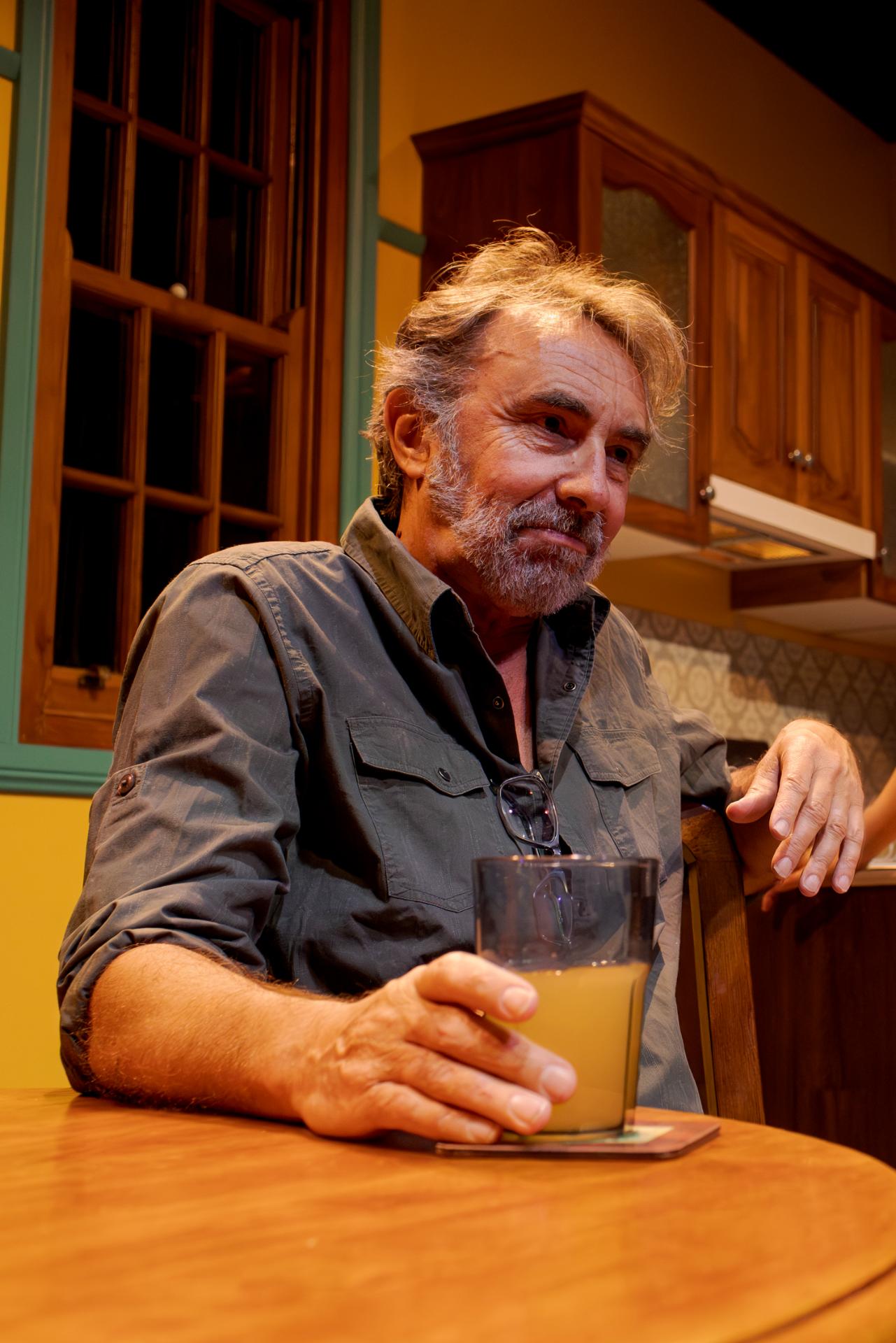

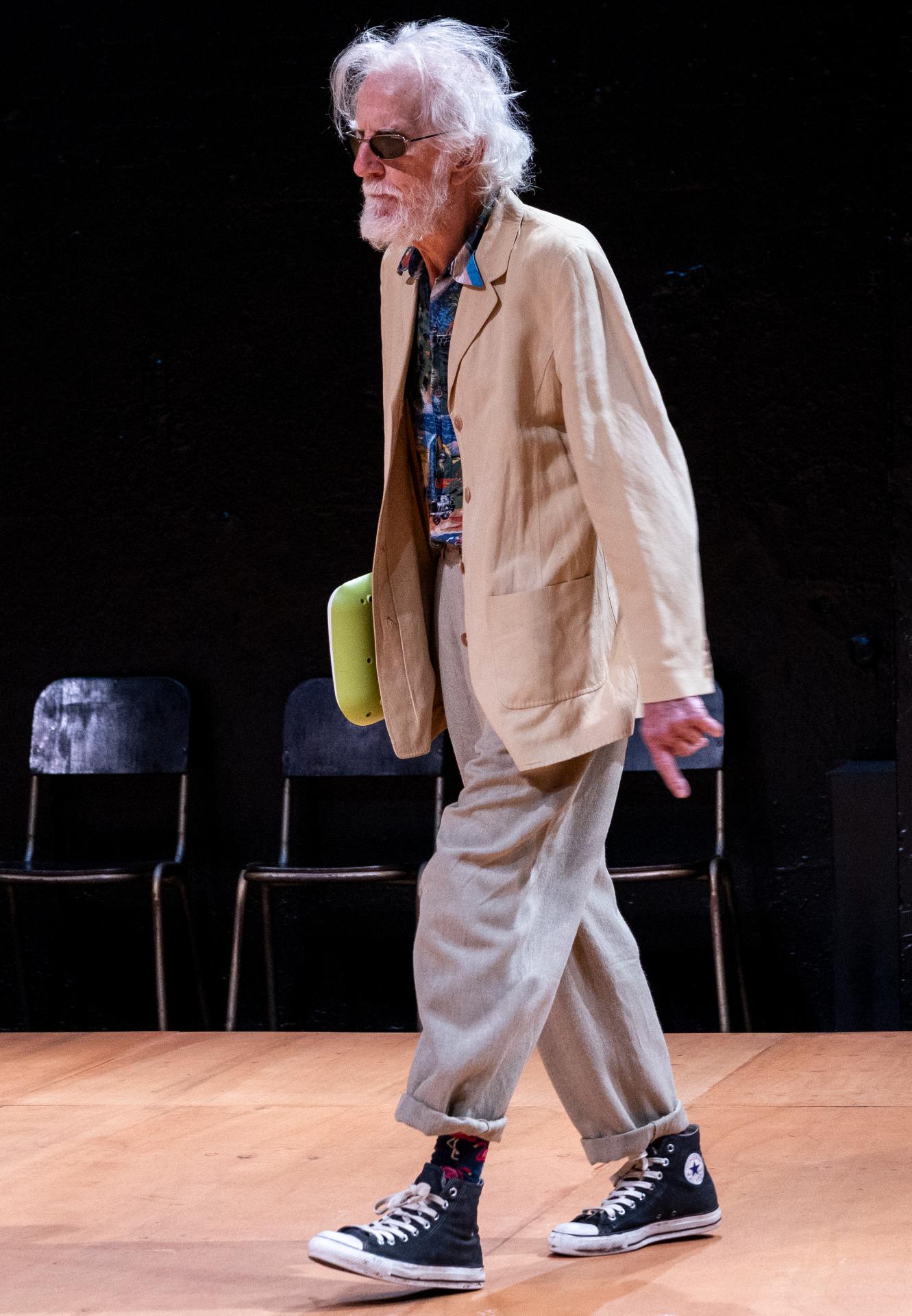

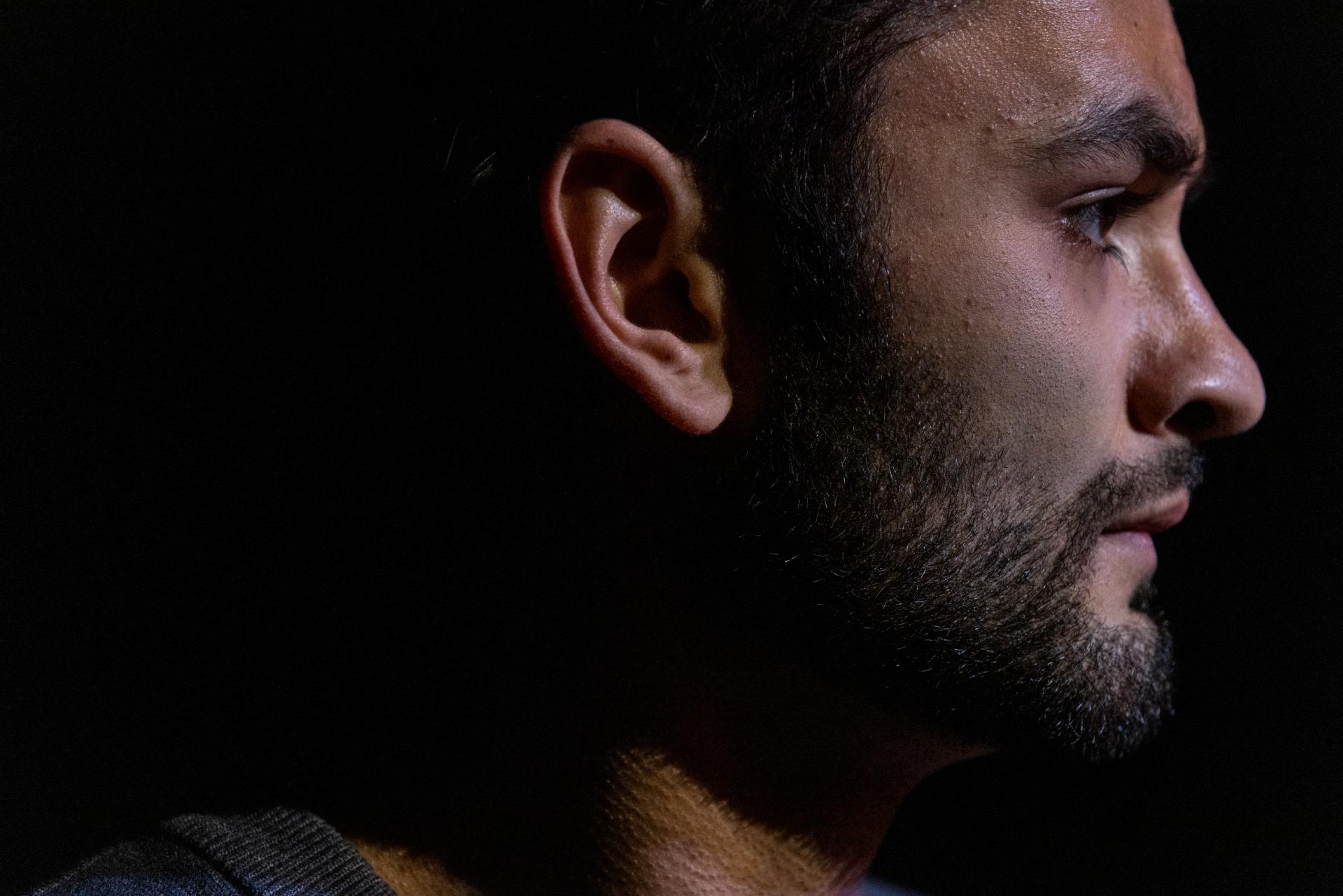

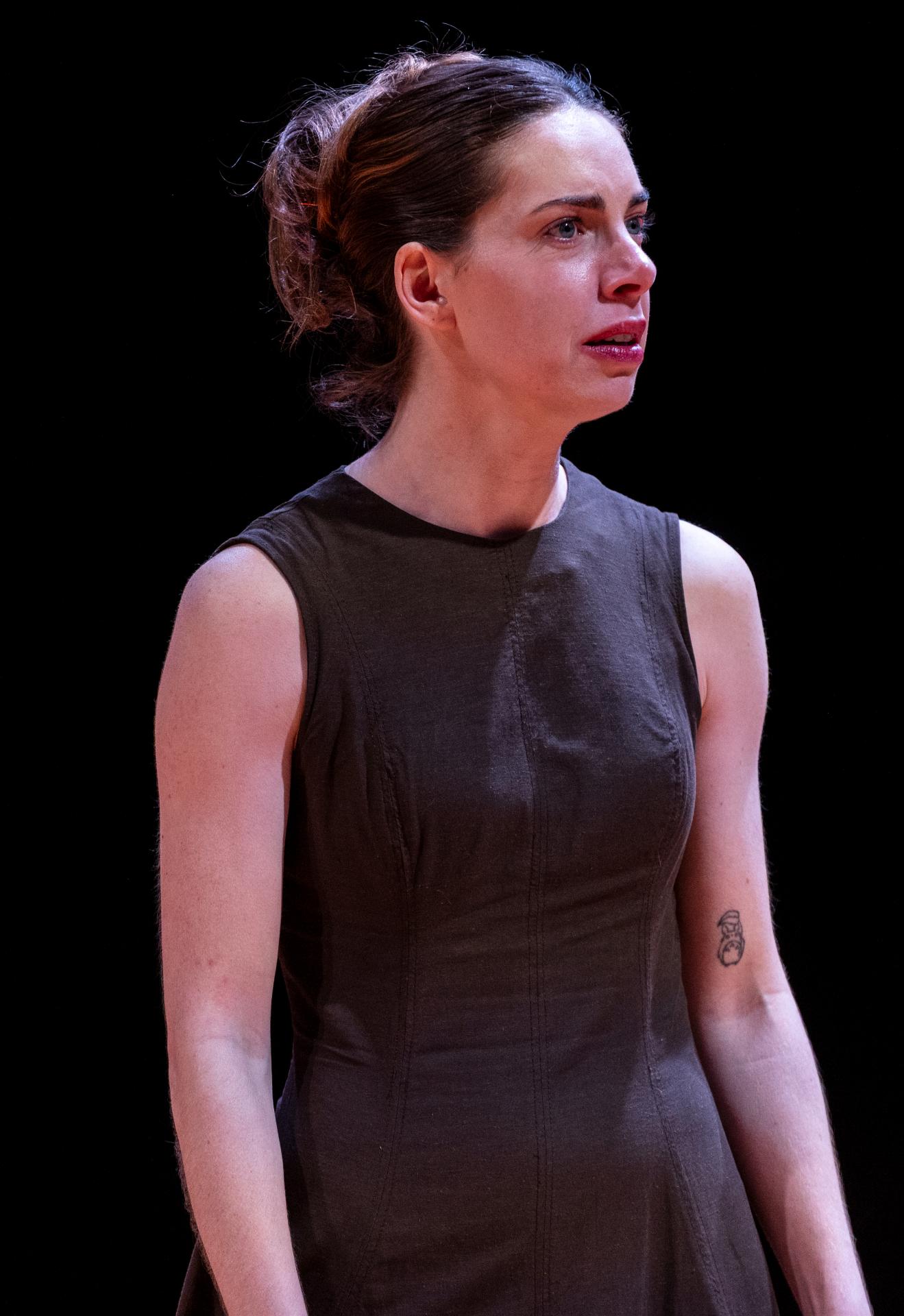

Cast: Annie Byron, Eloise Snape, Fay Du Chateau, Erika Ndibe, Charlotte Salusinszky

Images by Robert Catto

Theatre review

Esme has turned seventy-one, and the encroachment of dementia is becoming unmistakable. Her de facto partner of thirty-six years, Flo, remains steadfast in her commitment to care for Esme at home. Yet Esme’s son, asserting familial authority, is equally resolved to relocate her to an aged care facility. In Es & Flo, Jennifer Lunn examines a predicament all too familiar to many same-sex couples of a certain generation: the systematic erasure of their relationships by both kin and legal institutions, stripping them of companionship and patrimony precisely when bodily decline renders them most vulnerable.

It is a deeply affecting work, one that, under Emma Canalese’s astute direction, strikes precisely the right register to resonate with its audience, delivering a theatrical experience at once moving and meaningful. Annie Byron is particularly compelling as Esme, capturing with remarkable subtlety the complex metamorphoses that accompany the advance of age. Her portrayal of authentic tenderness toward her partner does much to render their bond credible, thereby securing the audience’s emotional investment in the narrative. Fay Du Chateau’s Flo truly comes into her own as the drama intensifies, revealing layers of fortitude and vulnerability. The supporting ensemble—Eloise Snape, Erika Ndibe, and Charlotte Salusinszky—likewise distinguishes itself, bringing thoughtfulness and nuance to every moment.