Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Jan 8 – 25, 2026

Playwrights: Isaac Drandic, John Harvey (adapted from the anthology by Thomas Mayo)

Director: Isaac Drandic

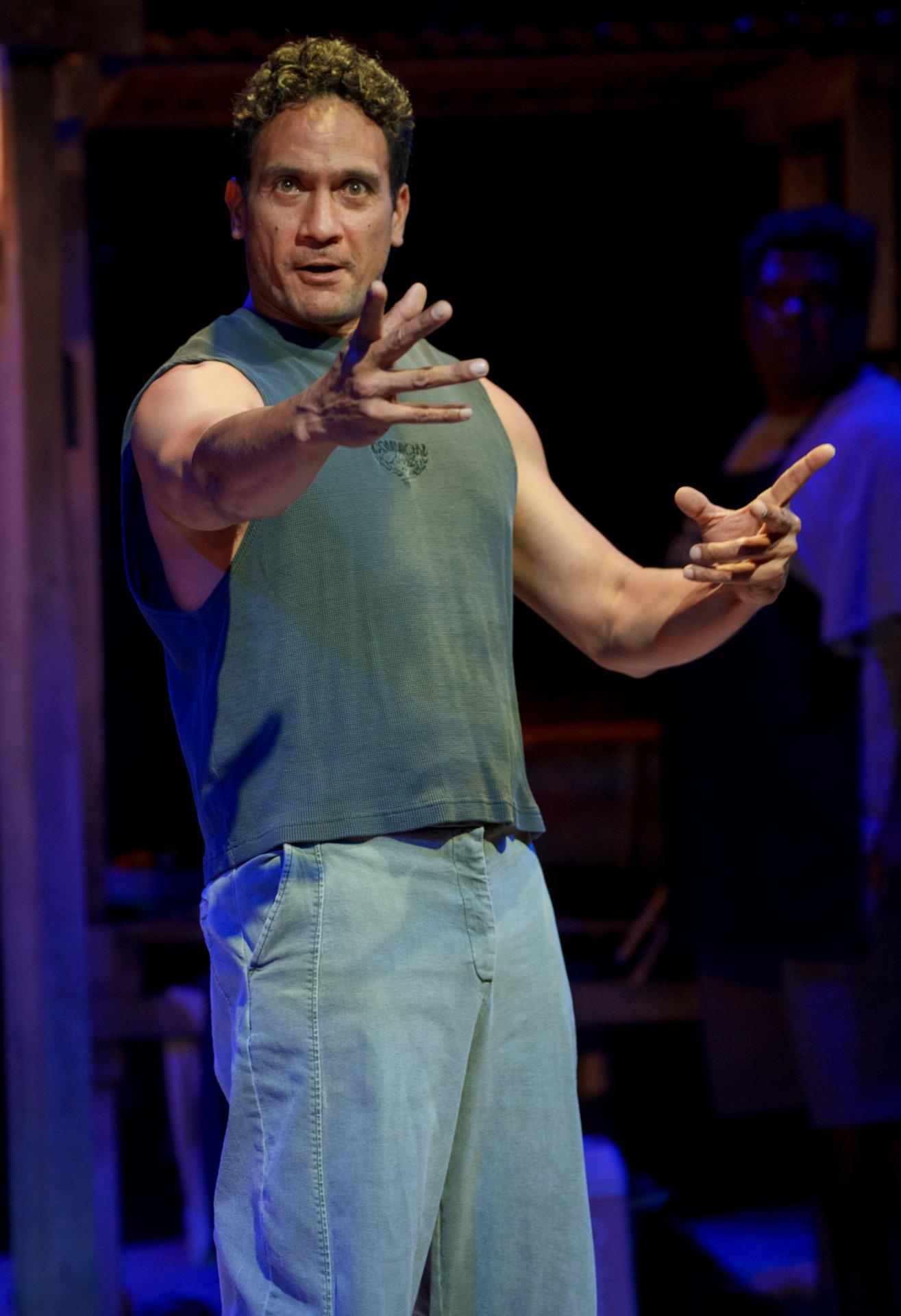

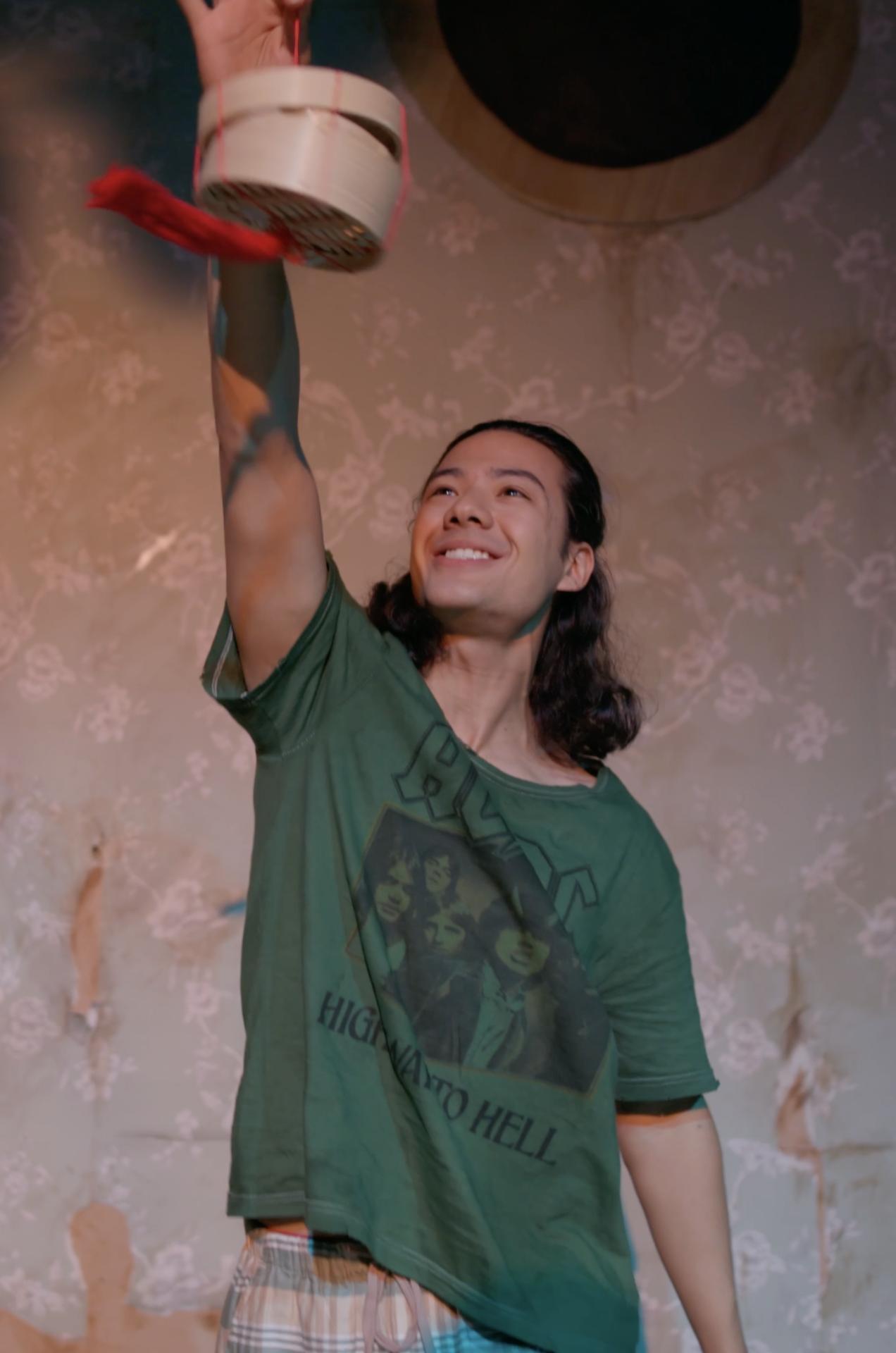

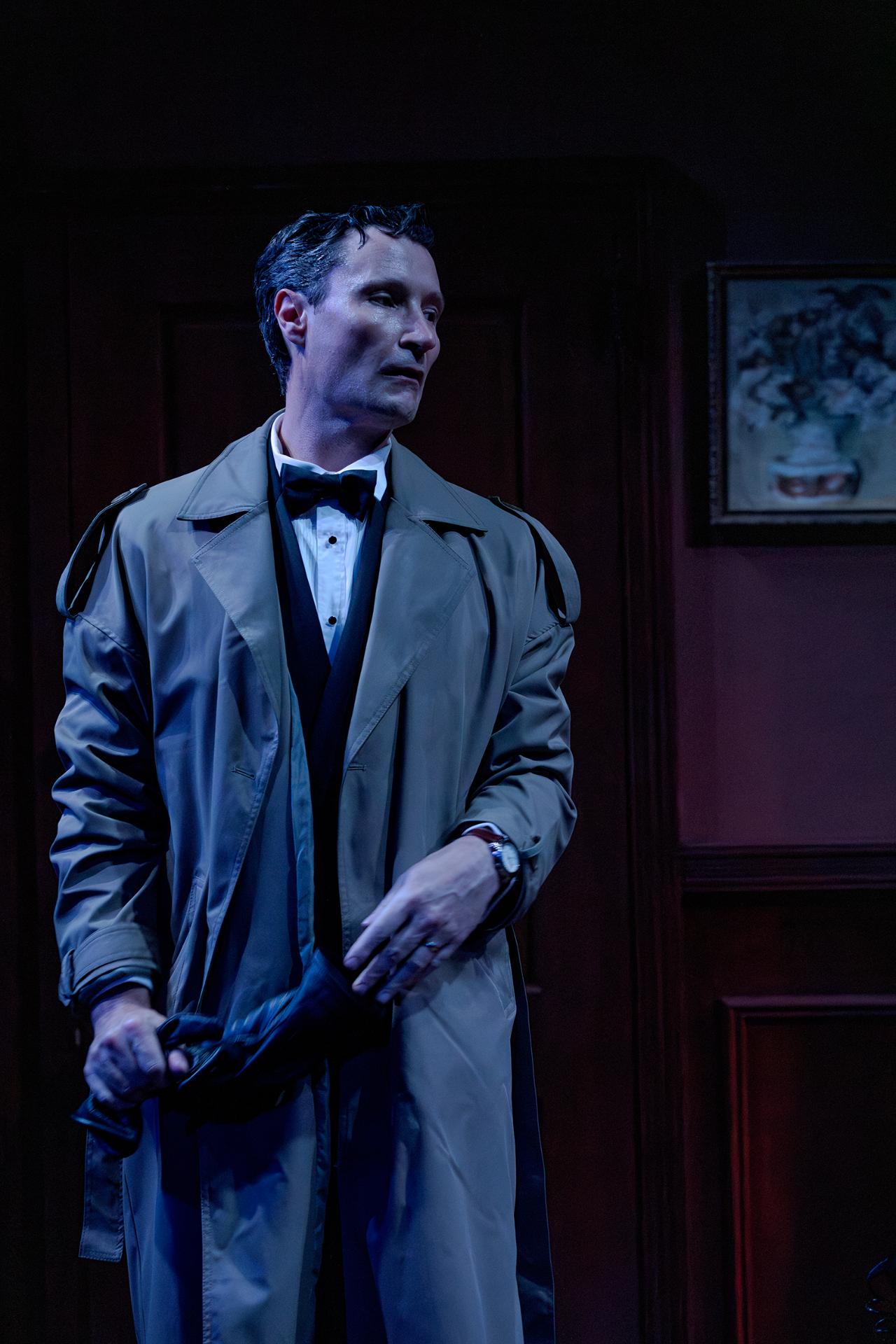

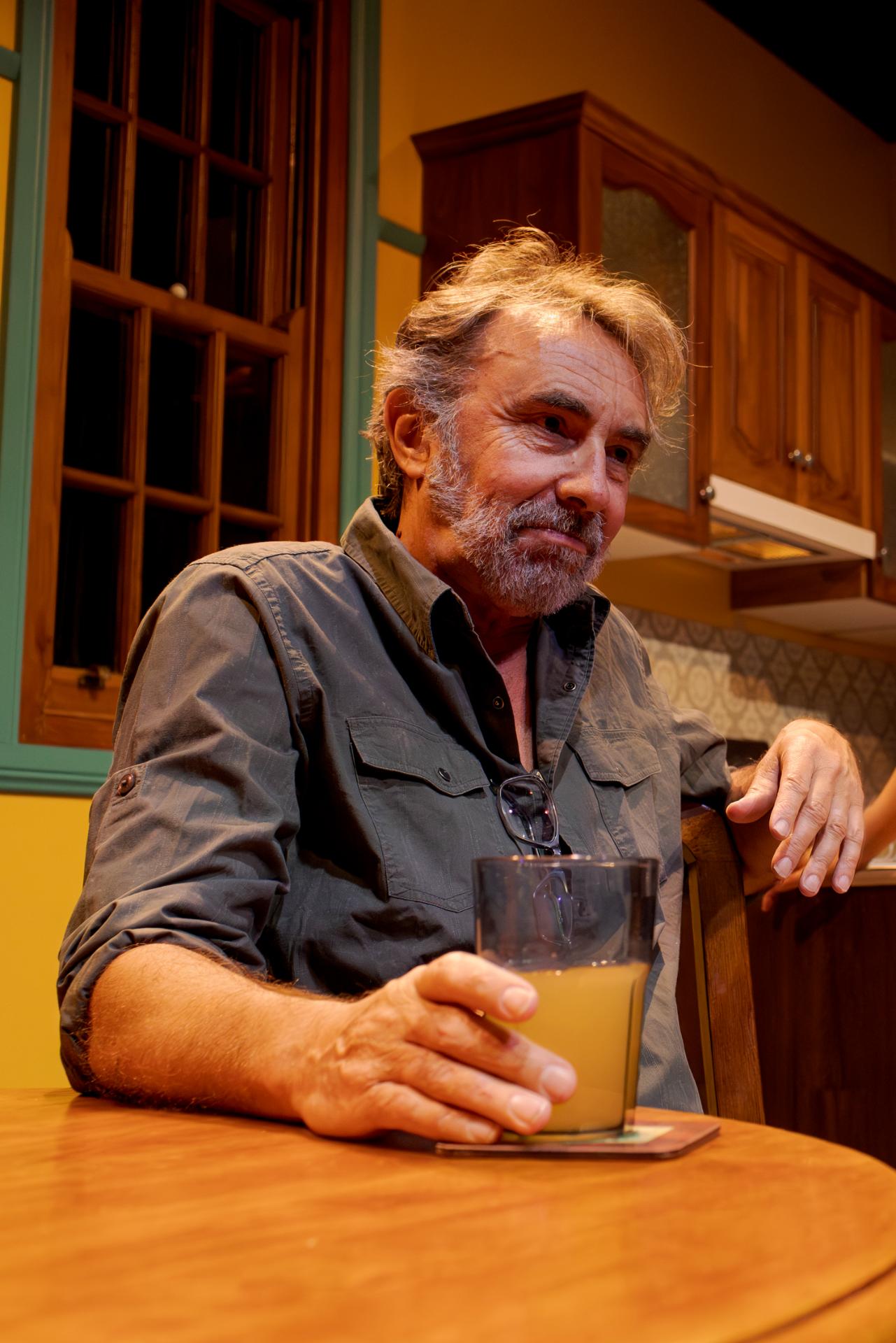

Cast: Jimi Bani, Waangenga Blanco, Isaac Drandic, Kirk Page, Tibian Wyles

Images by Stephen Wilson Barker

Theatre review

Based on Thomas Mayo’s 2021 book of the same name, this stage adaptation of Dear Son brings to life twelve letters written by Indigenous men to their sons and fathers. Adapted by Isaac Drandic and John Harvey, the work translates Mayo’s exploration of love and vulnerability into theatrical form, extending his interrogation of modern masculinity beyond the page. In doing so, it reimagines how men on these lands might speak to one another—seeking to dismantle the harmful and toxic norms that have too often underpinned traditional models of male behaviour.

Framed as a men’s group gathered around a campfire, with the letters spoken into lived, embodied presence, Drandic’s direction of Dear Son foregrounds the intimacy that can exist between men. The production reveals the depth of emotional support made possible when fear, shame, and embarrassment are set aside, allowing connection and care to take their place.

Kevin O’Brien’s set design anchors the production in an earthy, grounded sensibility, while Delvene Cockatoo-Collins’s costumes lend each character a sense of everyday authenticity. David Walters’s lighting is emotionally resonant throughout, shaping each moment with care, and Wil Hughes’s sound design infuses the work with a quiet tenderness that gently guides and deepens our empathetic response.

Jimi Bani, Waangenga Blanco, Isaac Drandic, Kirk Page and Tibian Wyles comprise an ensemble representing First Nations men from across the continent. Each performer brings dignity and clarity of intention, and together their easy chemistry renders these portrayals of aspirational masculinity wholly convincing—models grounded in care, accountability, and a shared commitment to healing, both personal and communal. In their hands, healing is not an abstract ideal but a lived, generous practice—one that reaches outward, inviting audiences to imagine its possibilities for themselves.