Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Oct 7 – 26, 2025

Playwright: Gabrielle Scawthorn

Director: Gabrielle Scawthorn

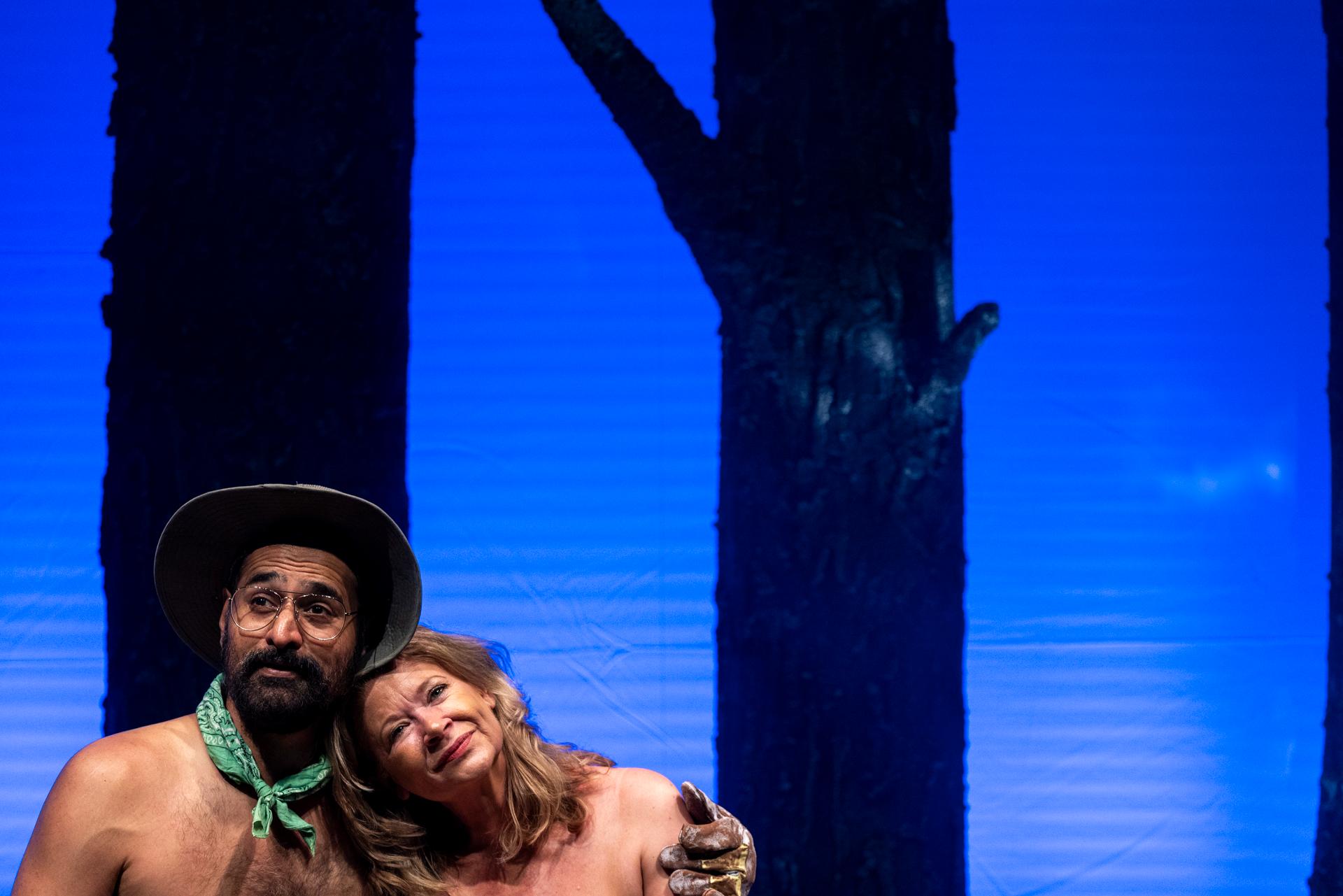

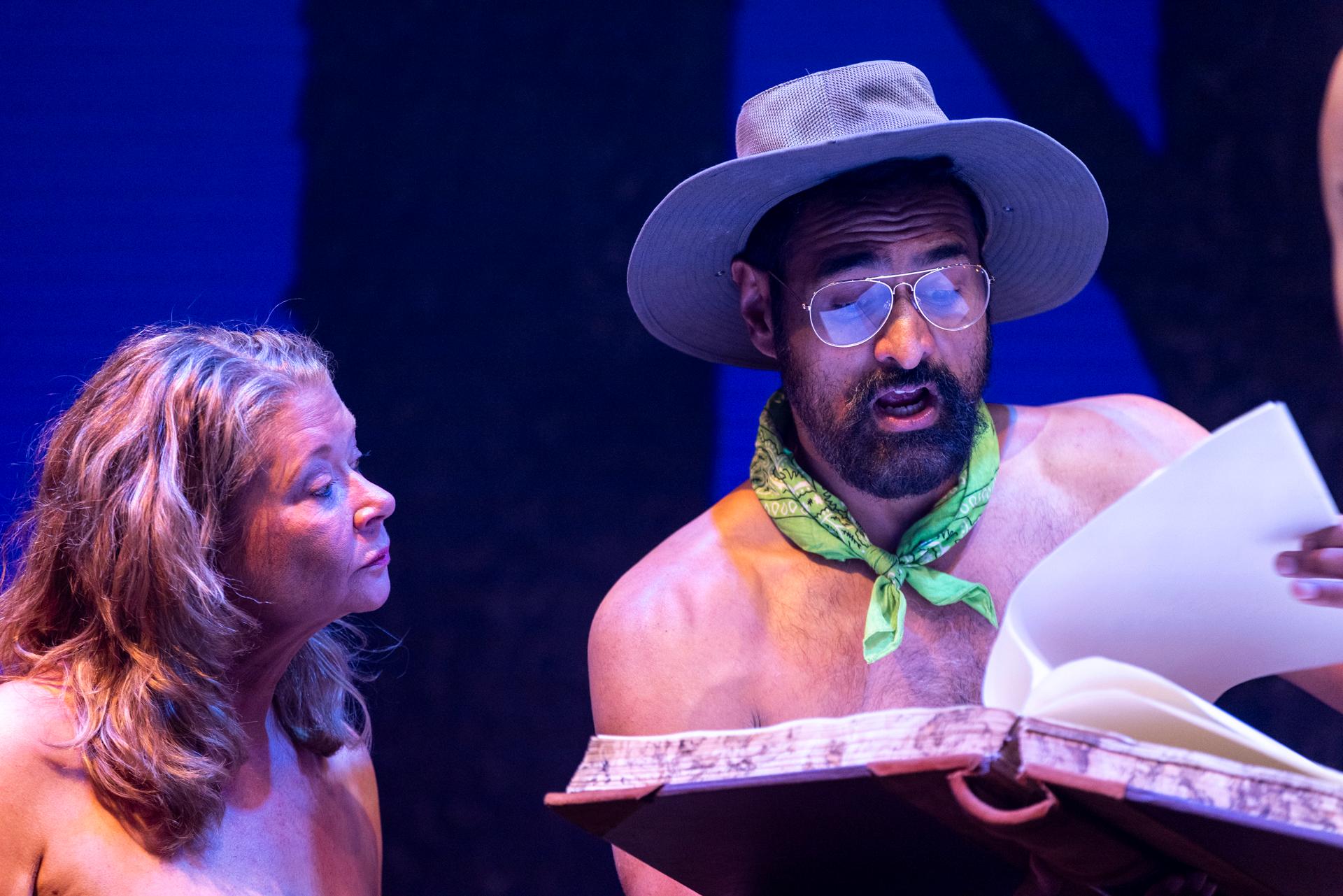

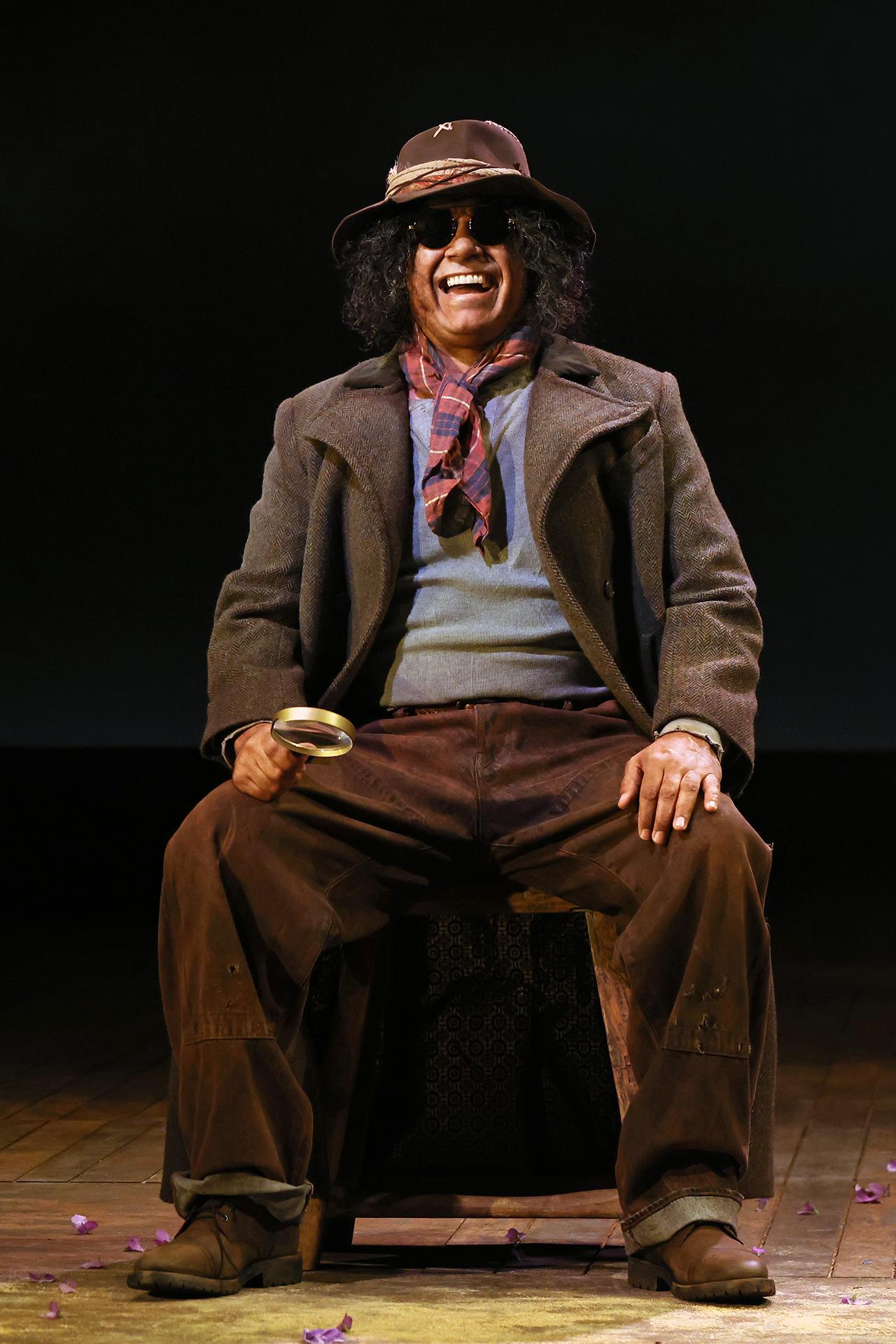

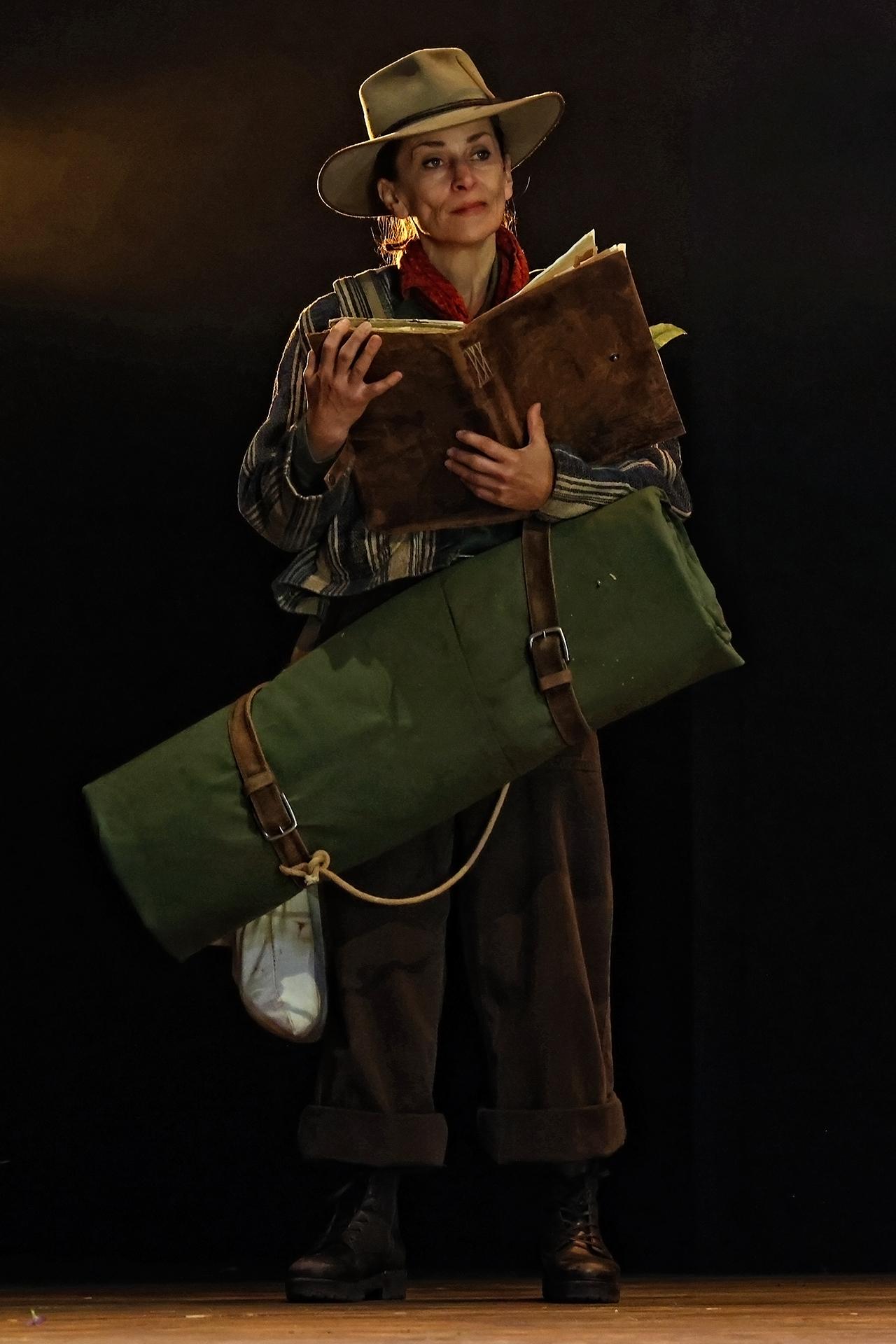

Cast: Iolanthe, Matilda Ridgway

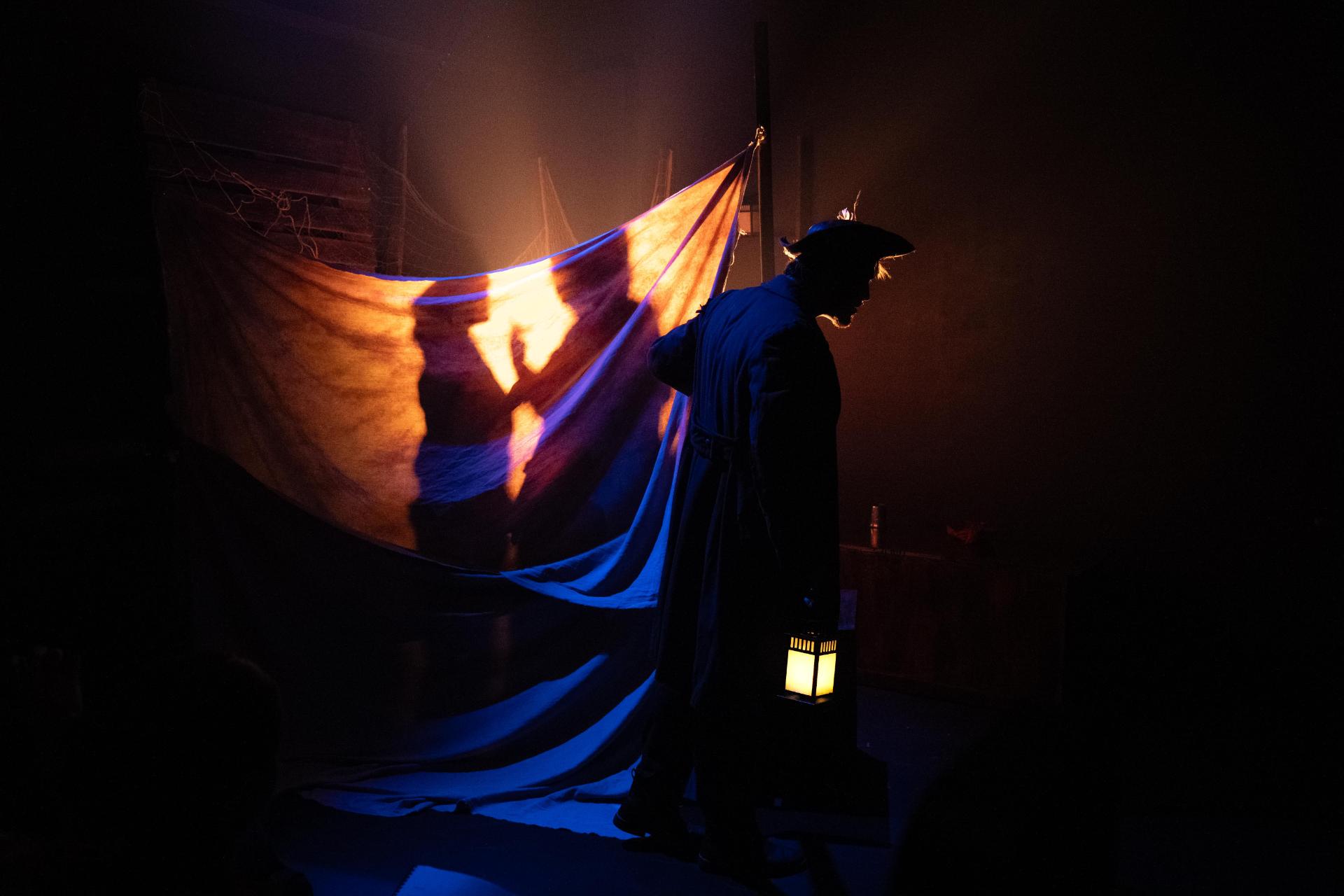

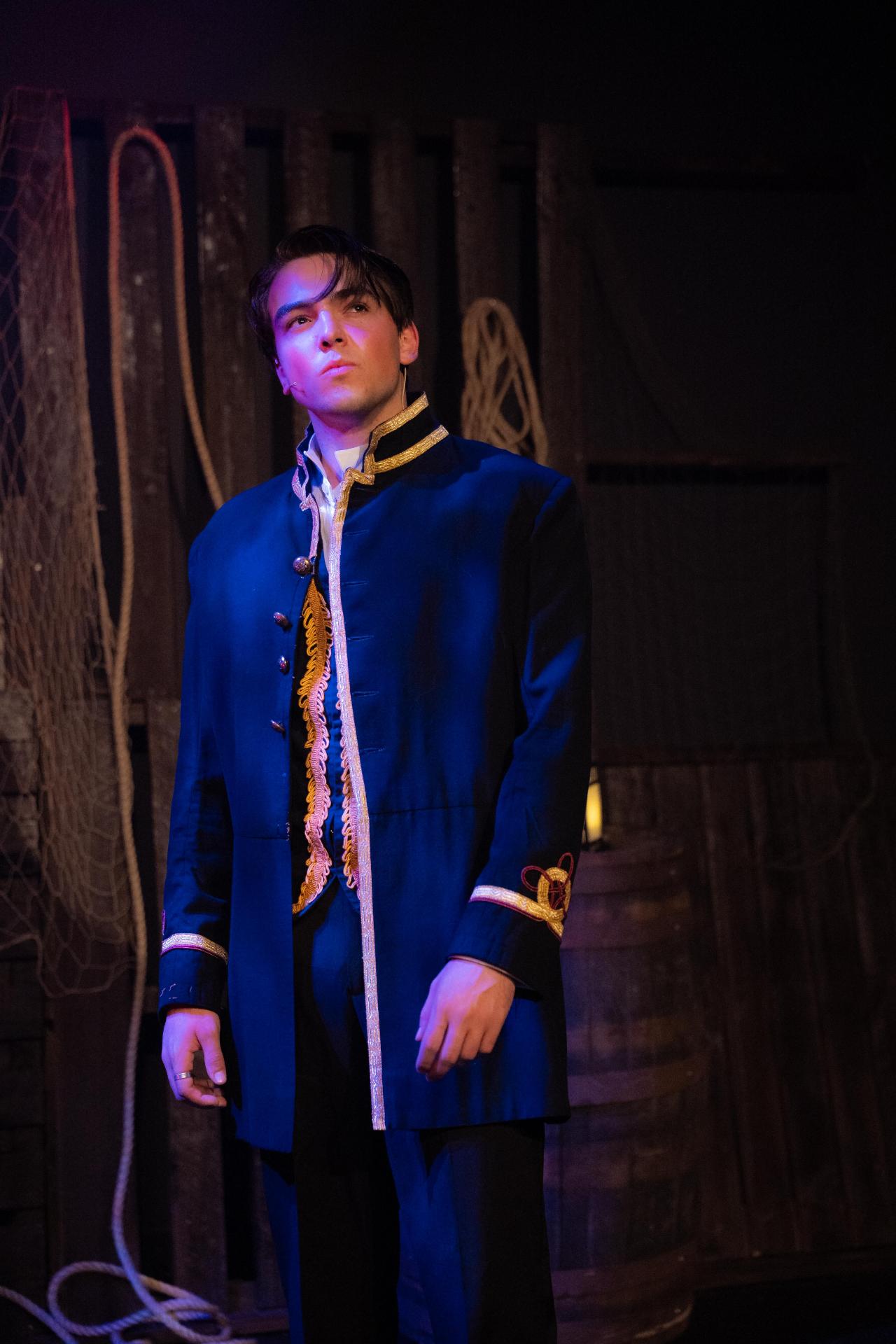

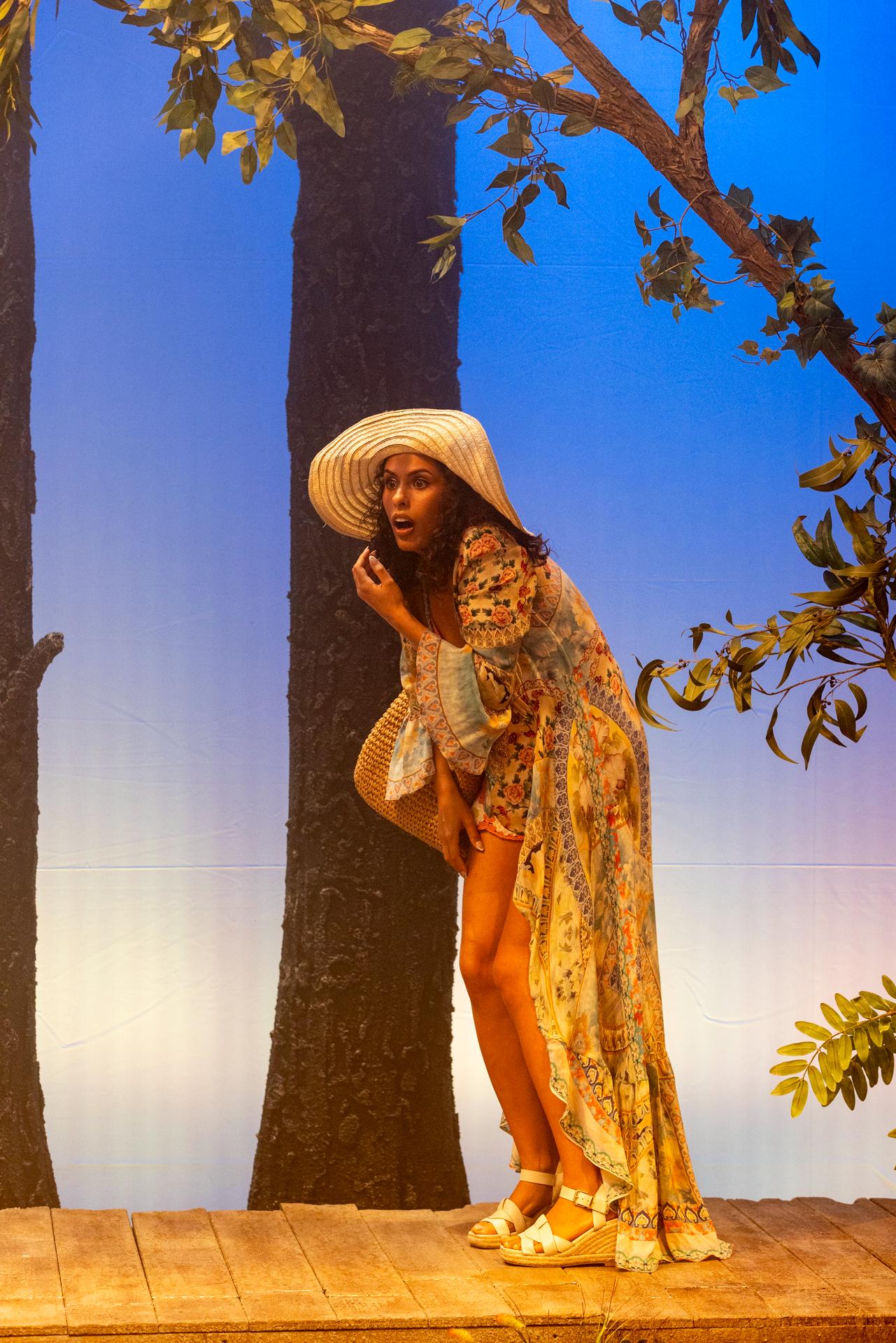

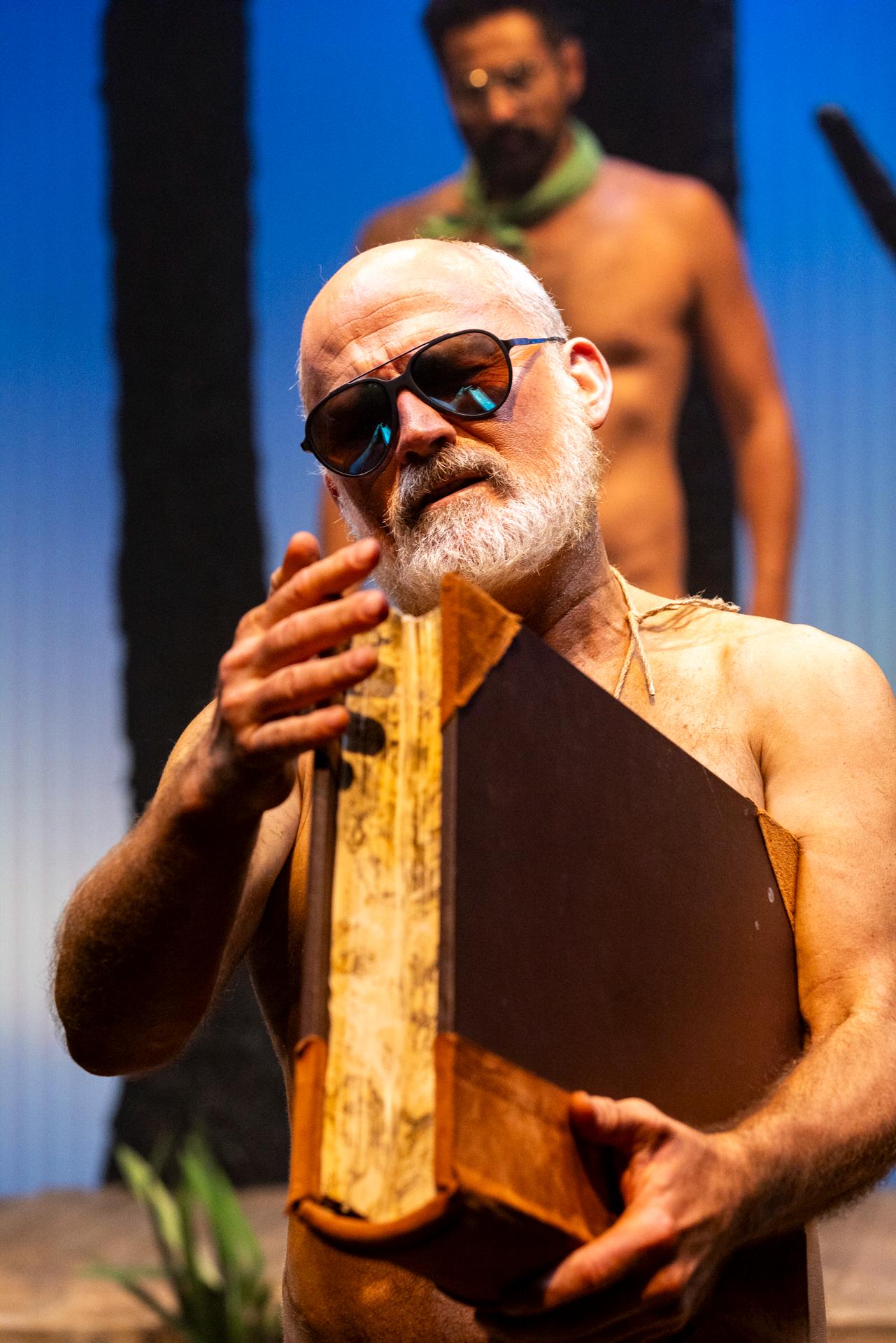

Images by Robert Catto

Theatre review

Nia signs up for a reality dating show, while producer Jess hovers nearby to ensure the illusion of love unfolds without a hitch. But when the pair are caught up in a devastating incident, what surfaces isn’t the expected solidarity between women, but a betrayal so stark it throws everything into question. Gabrielle Scawthorn’s The Edit is a piercing look at the stranglehold of late capitalism on contemporary womanhood — and how easily we can slip into exploiting one another in pursuit of success. Rather than rallying against the forces that divide and commodify, we too often become willing participants in our own undoing.

Scawthorn’s writing is incisive and richly layered, full of surprising twists and morally complex characters that keep us alert and uneasy. As director, she delivers the work with unrelenting intensity and passion, sustaining a charged atmosphere from start to finish. The Edit is intellectually rigorous and emotionally fraught, most rewarding when it allows us fleeting glimpses into who these women truly are beneath the spectacle.

As Nia, Iolanthe offers an intriguing study of ambition under late capitalism, portraying with disarming authenticity the moral dissonance required for success. Her performance captures a young woman’s conviction that intelligence and charm can transcend systemic exploitation, a belief that we observe to be both seductive and self-defeating. Matilda Ridgway’s interpretation of Jess is marked by remarkable psychological acuity; her disingenuousness feels neither exaggerated nor opaque, but grounded in a credible logic of survival. As the play unfolds, Jess becomes increasingly reprehensible, yet Ridgway’s depictions remain resolutely authentic, allowing us to perceive the structural and emotional pressures that shape such behaviour.

Set design by Ruby Jenkins cleverly frames the action with visual cues that expose the hidden machinery of television production, and the layers of deceit that sustain its manufactured fantasies. The stage becomes both a workplace and a trap — a reminder that behind every glossy image lies manipulation at work. Phoebe Pilcher’s lighting design is striking in its chill and precision, evoking the emotional coldness that governs human behaviour in a system built on economic cannibalism. Music and sound by Alyx Dennison heighten the drama with an organic subtlety; their contributions are seamlessly integrated yet undeniably potent in shaping the production’s tension and mood.

The pursuit of success feels almost instinctive, a shared ambition ingrained from an early age, yet its meaning remains troublingly mutable. What we come to define as “success” is so often shaped by external forces, by market logics and cultural expectations that reward ambition only when it conforms to the existing order. For the young, particularly those taking their first tentative steps into professional life, this pursuit can be both intoxicating and perilous. The world teaches its lessons harshly, and every triumph seems to come at the expense of something quietly vital.

We are endlessly seduced by the shimmer of promise, by images of prosperity, relevance, and acclaim, and in our hunger, we mistake the surface for substance. The capitalist dream markets itself as empowerment, yet its currency is exploitation. Still, we continue to invest in the system, not solely out of necessity but from an almost devotional belief that perseverance will one day grant transcendence. The tragedy, of course, is that such faith is misplaced. The machine does not elevate; it consumes. It extracts our labour, our time, our spirit, and gives back only a fleeting sense of validation before demanding more. In the end, the system does not nurture our aspirations; it feeds on them, leaving us diminished, yet still reaching, still convinced that the next victory will finally make us whole.

www.belvoir.com.au | www.legittheatreco.com | www.unlikelyproductions.co.uk