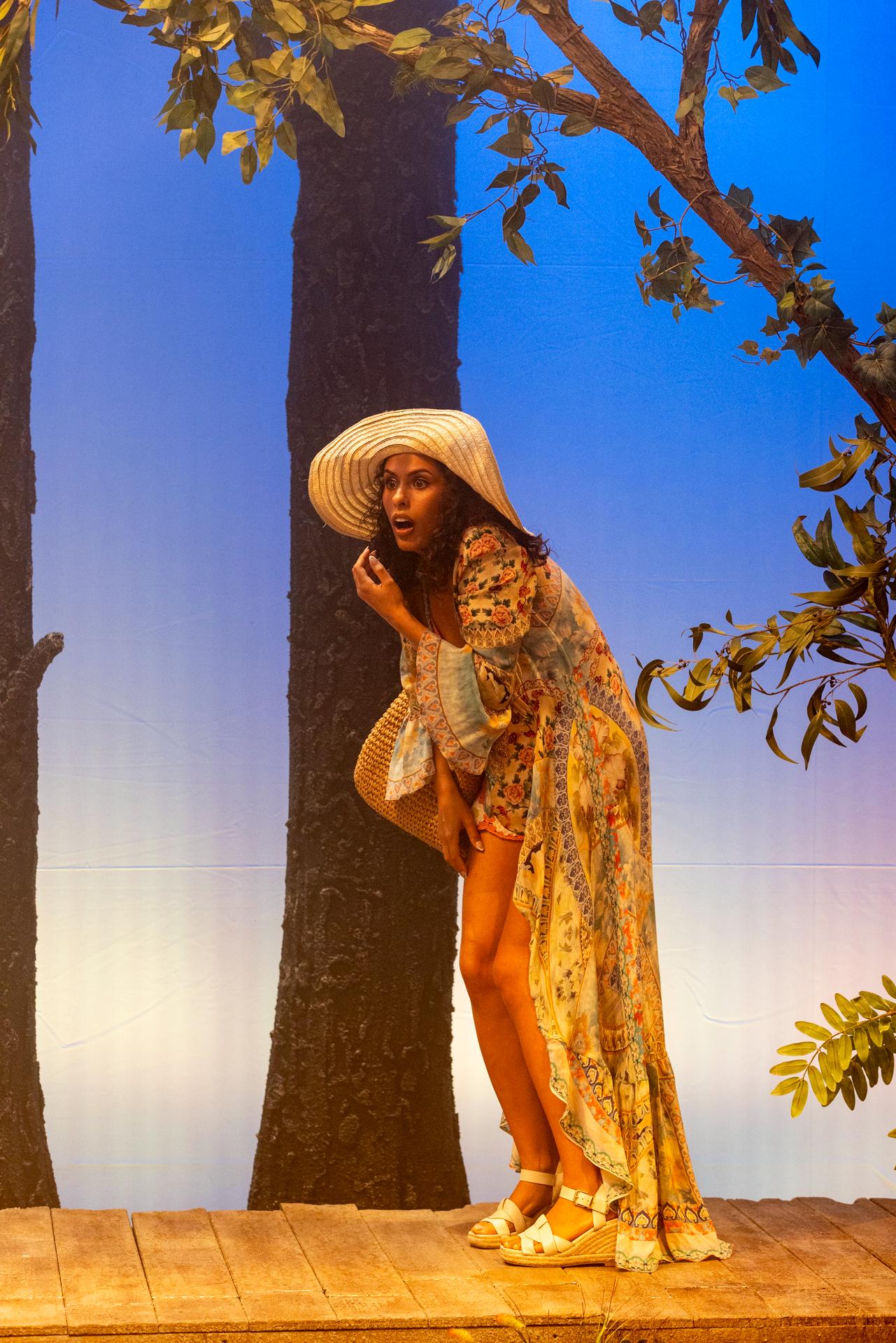

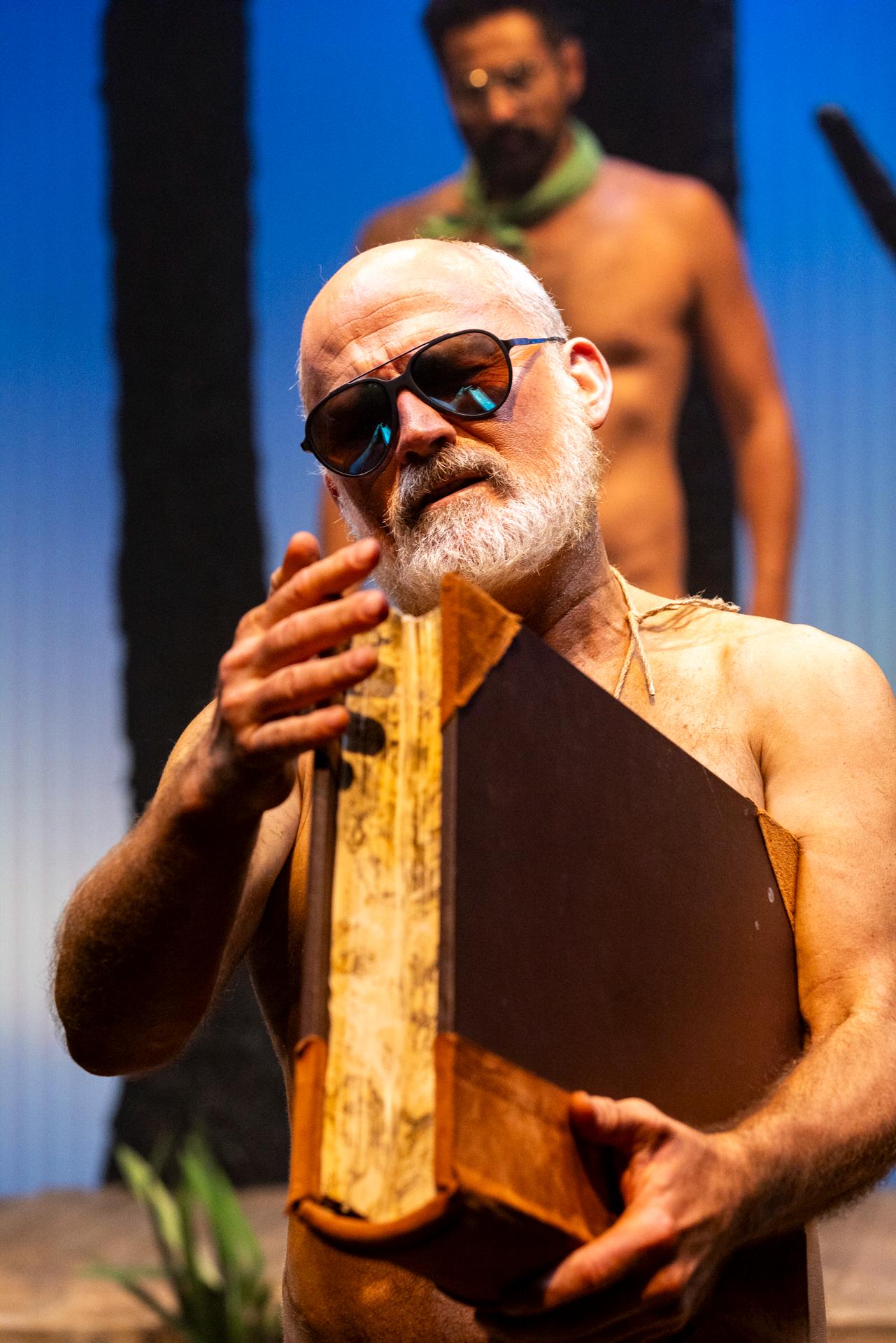

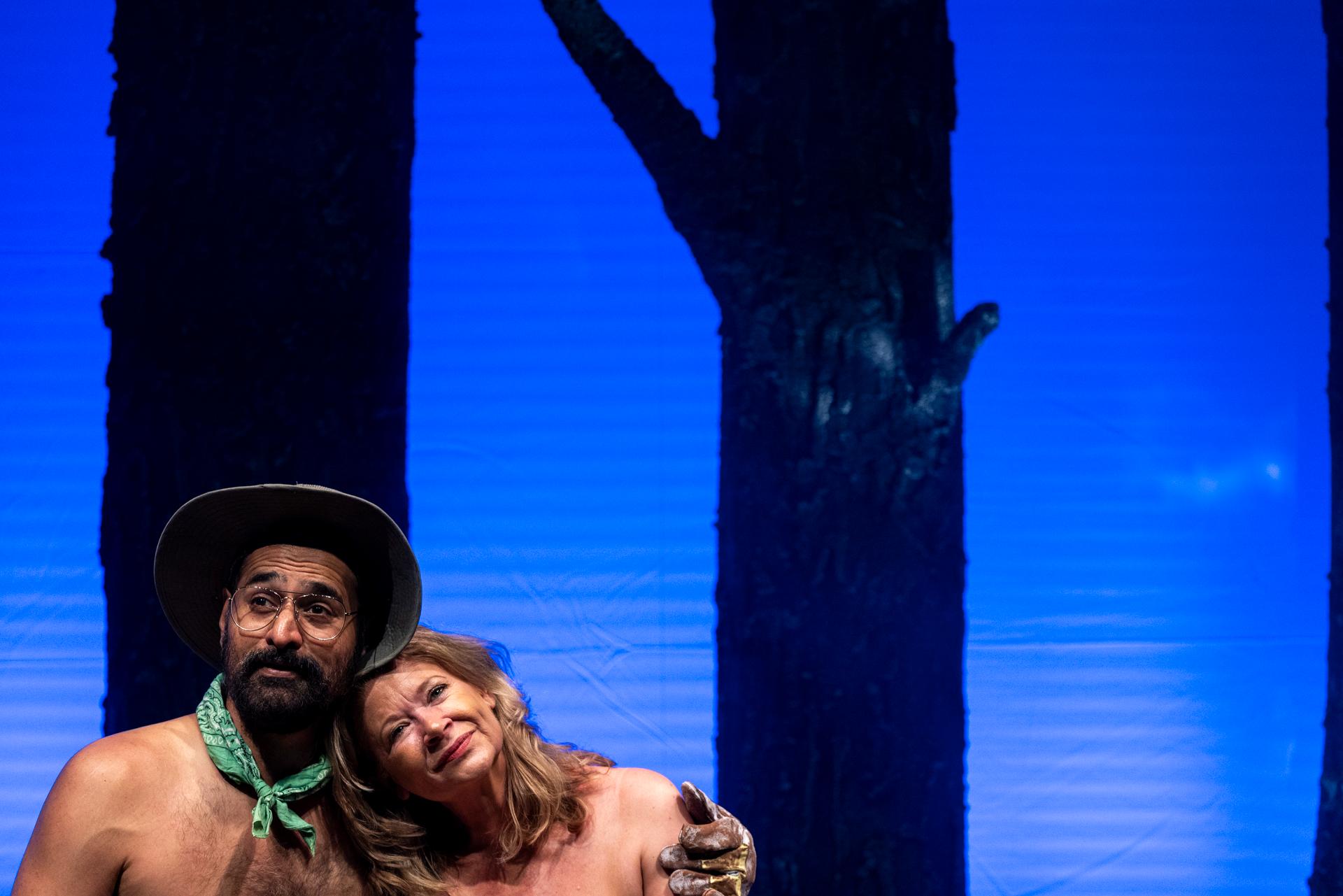

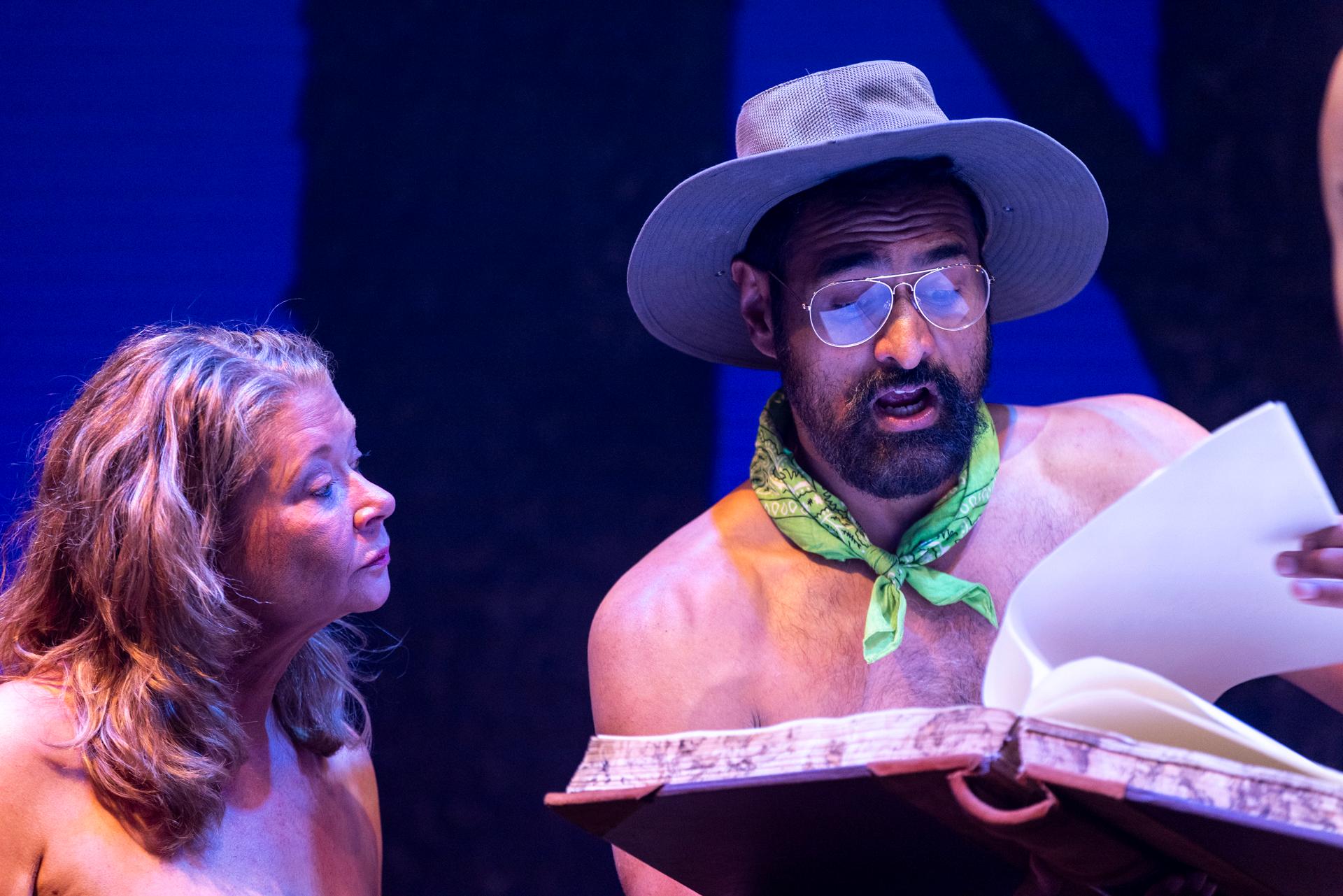

Venue: Old Fitzroy Theatre (Woolloomooloo NSW), Nov 7 – 22, 2025

Playwright: Douglas Maxwell

Director: Sam O’Sullivan

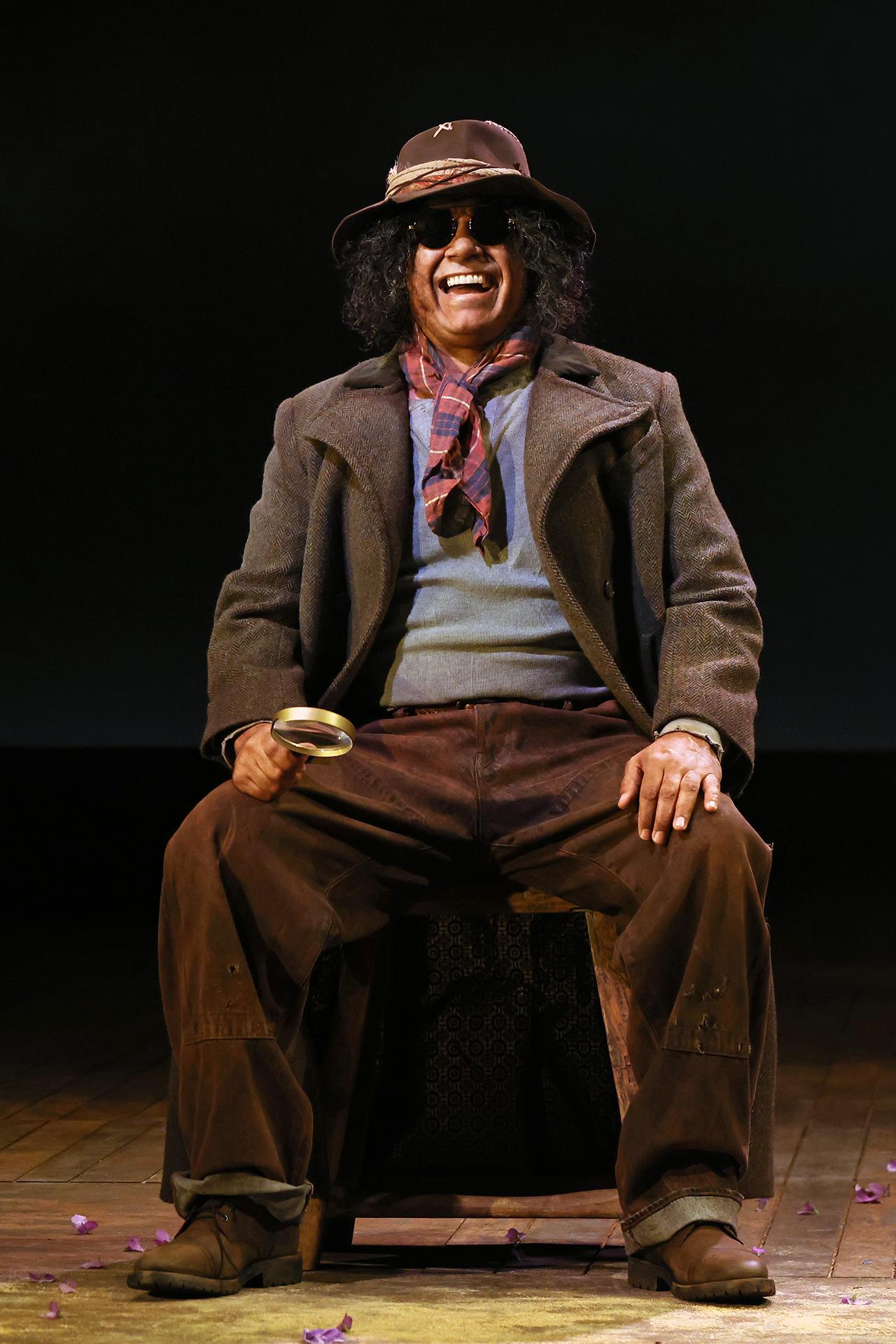

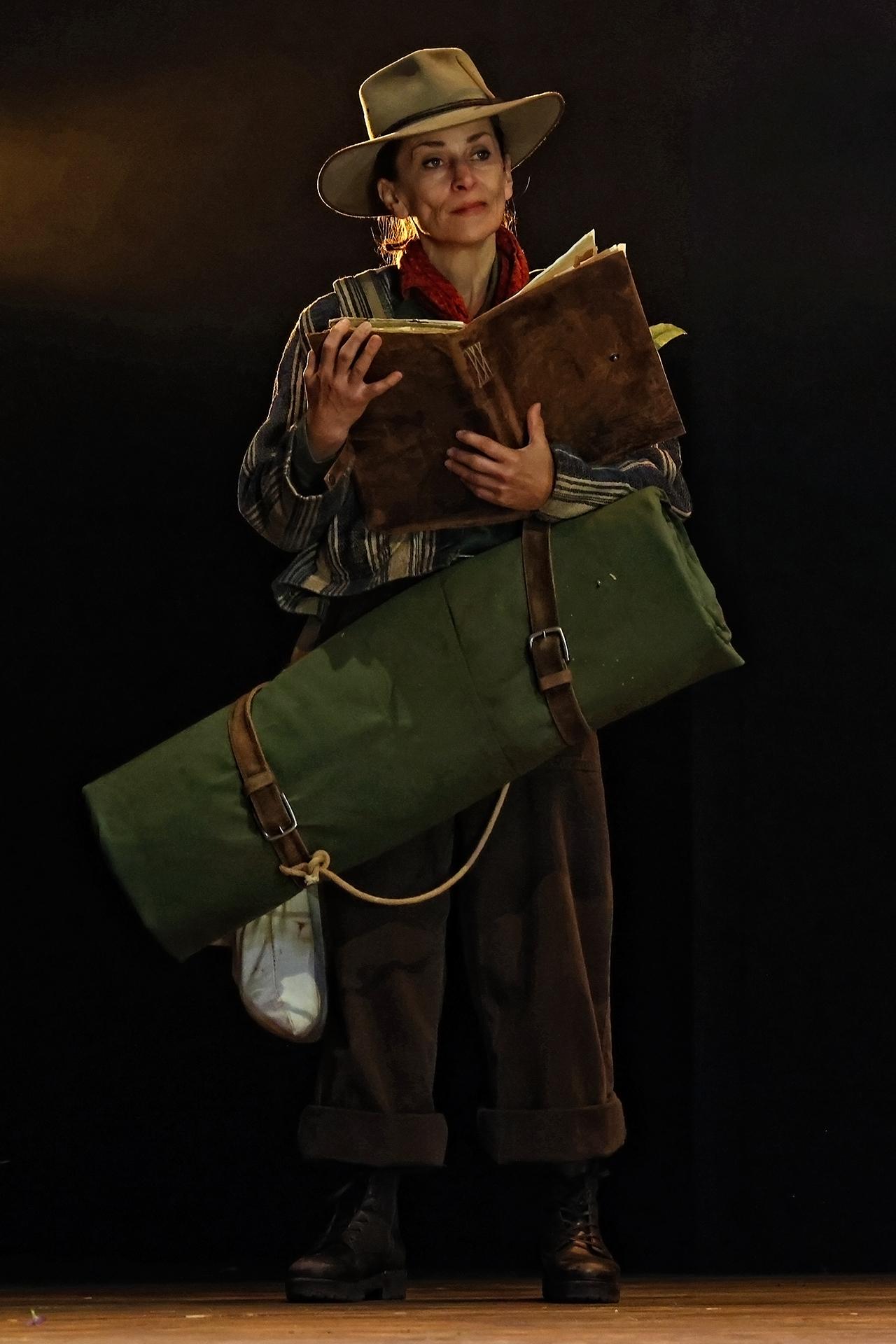

Cast: Aisha Aidara, Ainslie McGlynn, Henry Nixon, Jeremy Waters

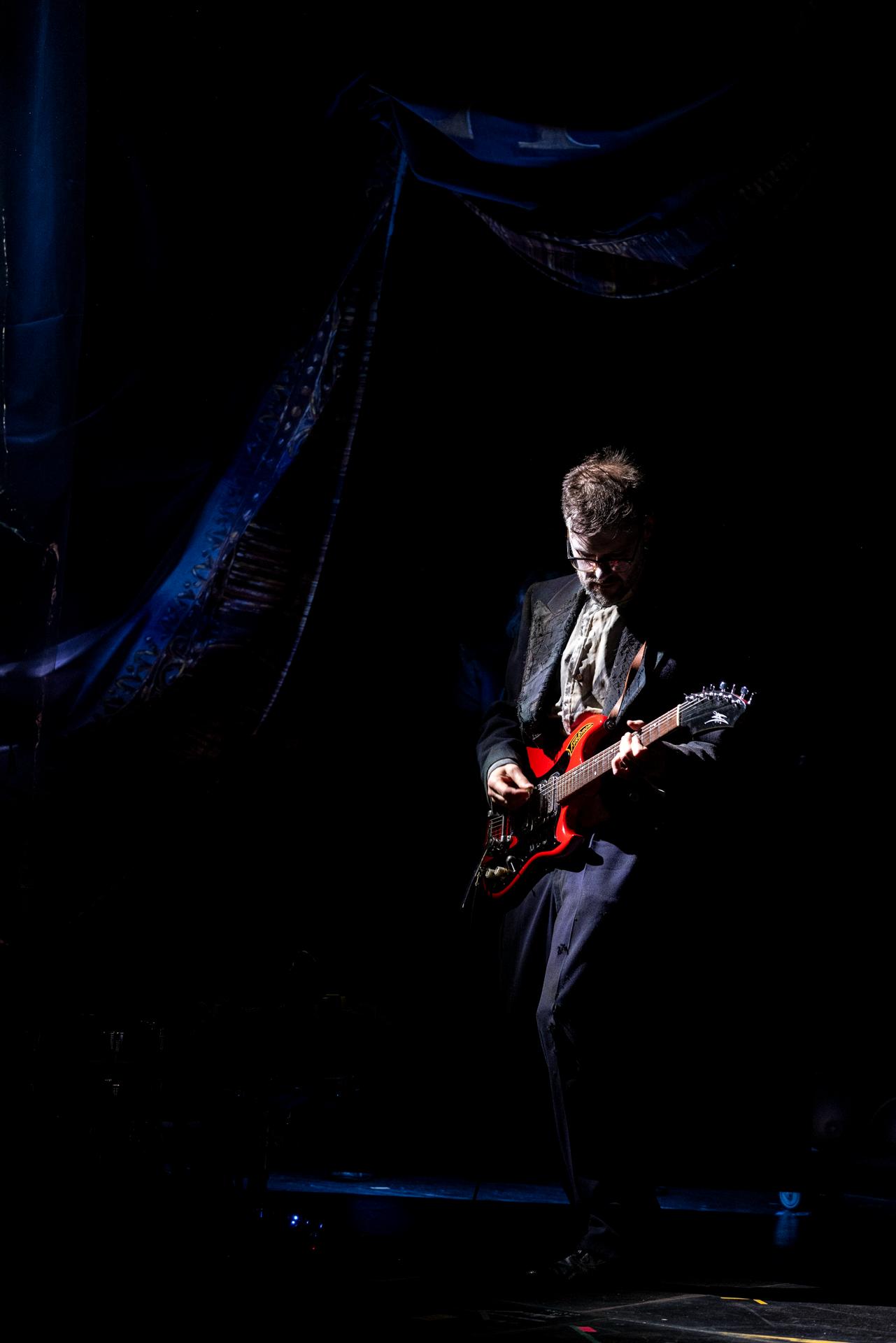

Images by Richard Farland

Theatre review

Just three months after Helen’s death, her husband Milo finds himself in love again—with Greta. When Helen’s best friend Liane learns the truth over dinner, her fury is as sharp as it is justified. In So Young, Douglas Maxwell turns his attention to grief, and to the bewildering variety of ways we try to survive it. His writing glimmers with wit and tenderness, and though he captures the ache of love and loss with real conviction, the story’s moral crescendo feels a shade too emphatic—leaving us moved, yet faintly smothered by its sincerity.

Sam O’Sullivan directs with a keen psychological instinct, guiding each confrontation with an honesty that keeps us firmly inside the characters’ heads. The production might benefit from sharper attention to its comedic undercurrents, but it never loses momentum, even as emotions flare and settle in quick succession. Kate Beere’s set design grounds the story in familiar domestic realism, while Aron Murray’s lighting is finely tuned to our shifting emotional responses. Johnny Yang’s understated sound work offers just enough texture to sustain our focus without distraction.

Aisha Aidara, Ainslie McGlynn, Henry Nixon, and Jeremy Waters are evenly matched in their performances, each as compelling as the next. Their portrayals are strikingly authentic, revealing with clarity and empathy the distinct emotional truths that collide within the play’s central argument. Through their efforts, we discover a touching immediacy, revealing how grief seeps into every connection, reshaping love and loyalty in its wake.

Time is the slow balm that touches every wound, even if it never truly restores what was lost. Sorrow and anguish are woven into the fabric of being alive, as constant as breath itself. The yearning to escape pain is ancient and human, yet in watching ourselves grieve, we learn what it means to endure. To see how we break is to see how we love—and how we might heal without hurting more. However impossible it feels, the truth endures: the living must matter more than the dead.