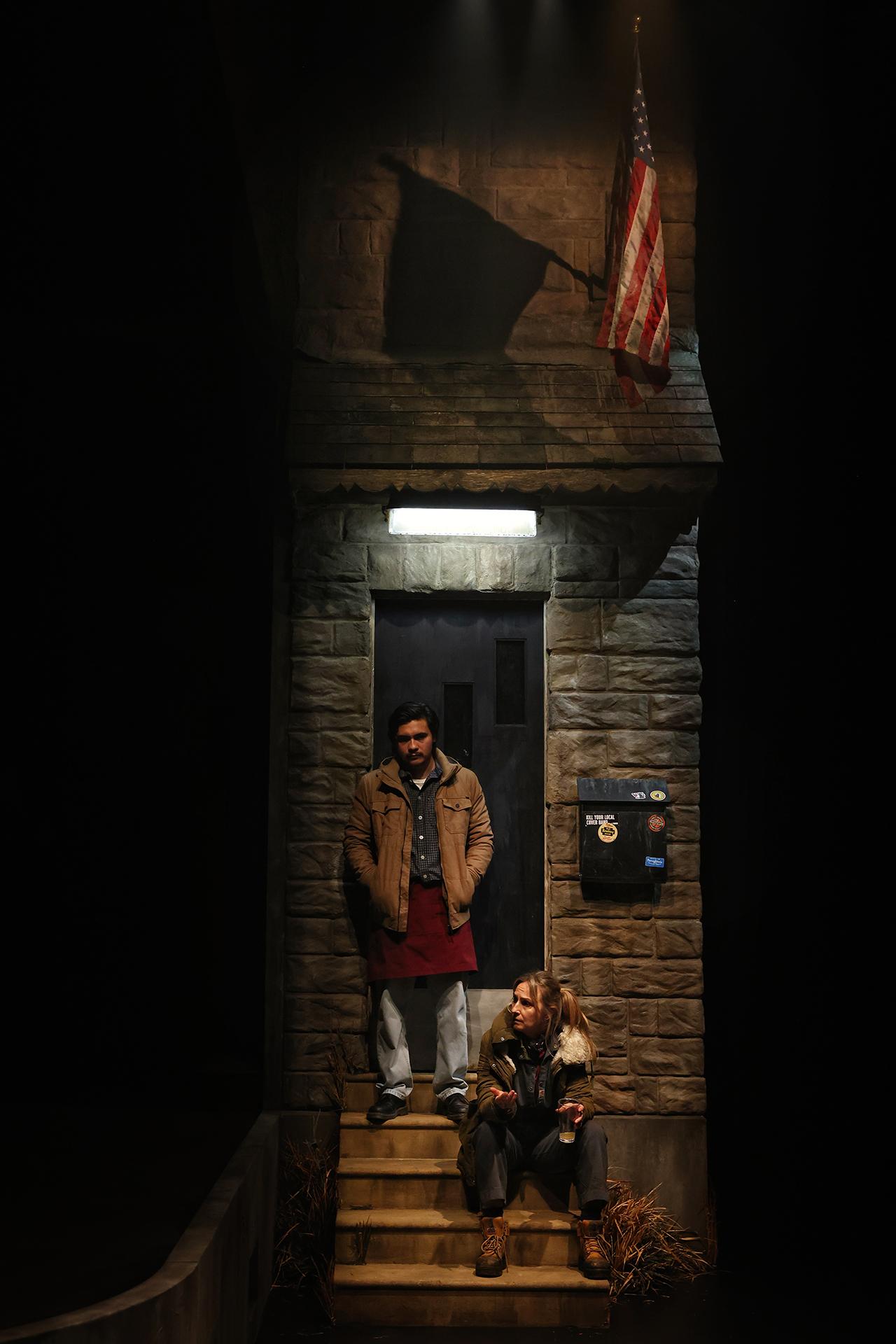

Venue: Wharf 1 Sydney Theatre Company (Walsh Bay NSW), Feb 2 – Mar 22, 2026

Playwright: Branden Jacobs-Jenkins

Director: Zindzi Okenyo

Cast: Grace Bentley-Tsibuah, Deni Gordon, Markus Hamilton, Tinashe Mangwana, Maurice Marvel Meredith, Sisi Stringer

Images by Prudence Upton

Theatre review

The Jaspers of Chicago are a prominent family, with patriarch Solomon having left an indelible mark on American history as a luminary of the Civil Rights movement and a pillar of his community, counting Dr Martin Luther King Jr. among his many friends. Yet, at some point, things began to unravel.

In Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ Purpose, we witness how a legacy can be tarnished, in a story that explores broken dreams, misplaced faith, and the quiet dangers of human complacency. As we discover that the Jaspers are not who they are believed to be, we are confronted with the illusory nature of celebrity and reputation, and reminded that true democratic agency — and personal destiny — ultimately demands individual vigilance and control.

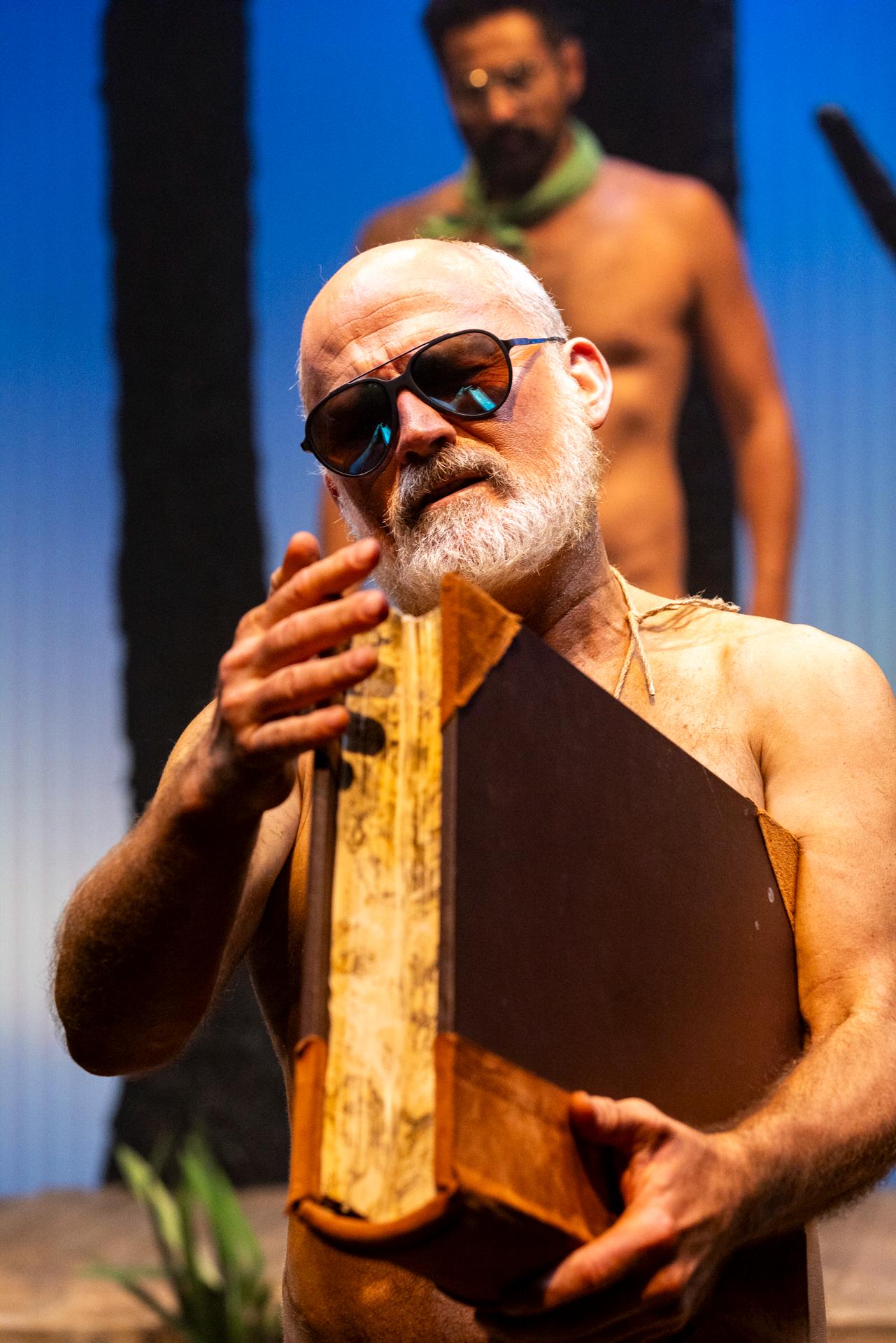

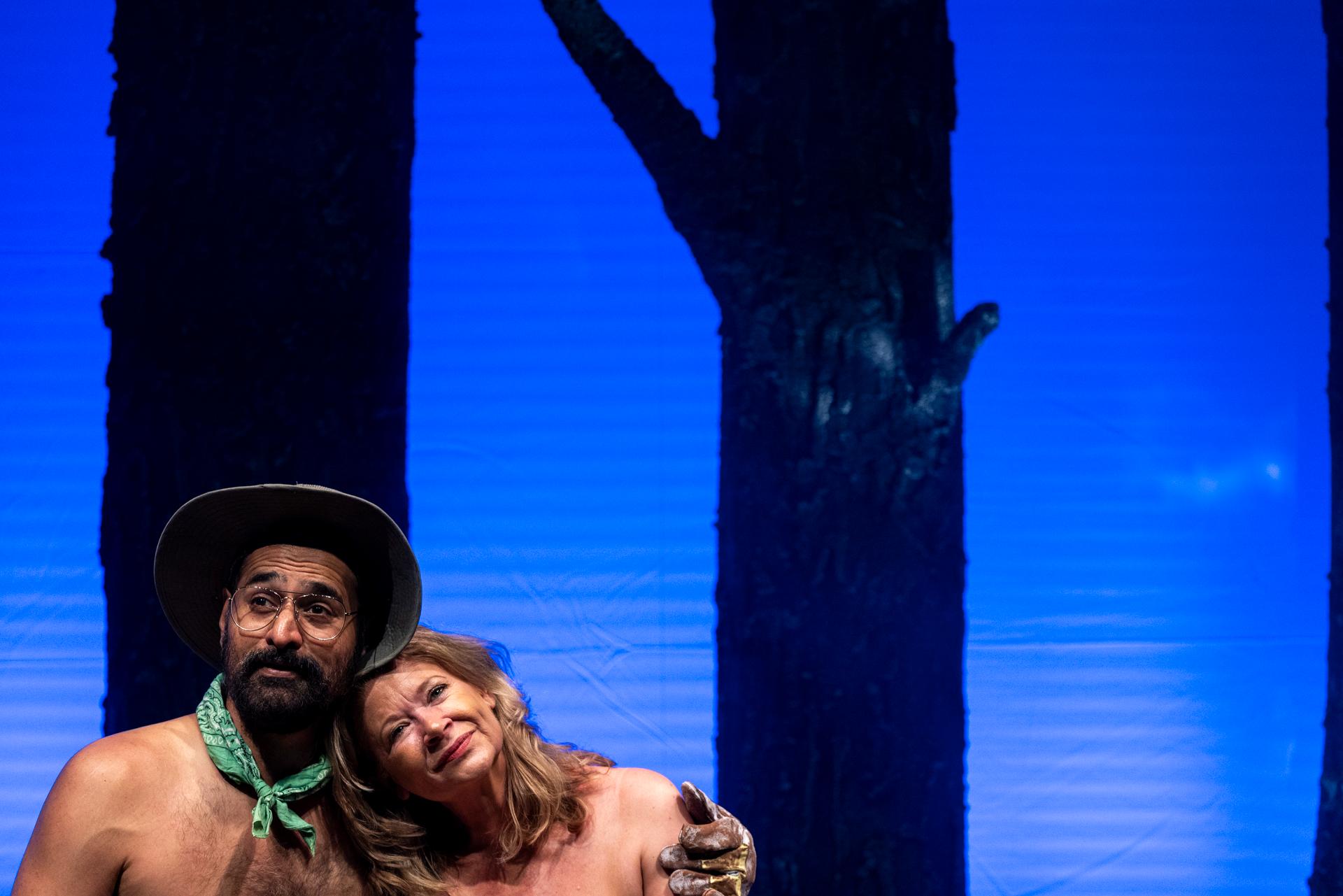

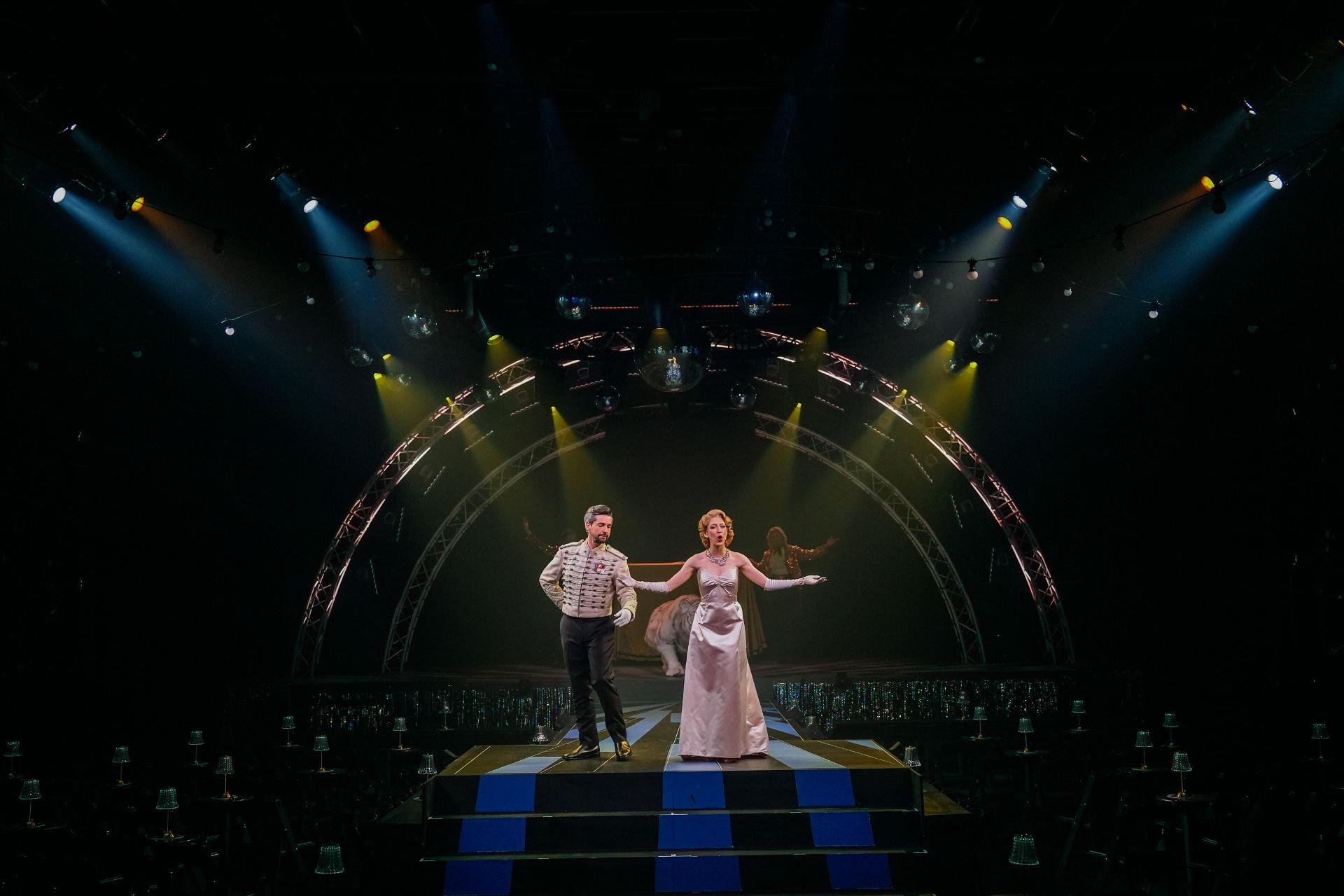

It is a sensational piece of writing, rich with humour and sharp insight, and driven by a plot that is thrillingly unpredictable. Zindzi Okenyo’s direction keeps the audience riveted as each dramatic surprise unfolds with sustained force. Under her guidance, the relationships feel fully realised and believable, allowing us to invest deeply in the complex dynamics at play.

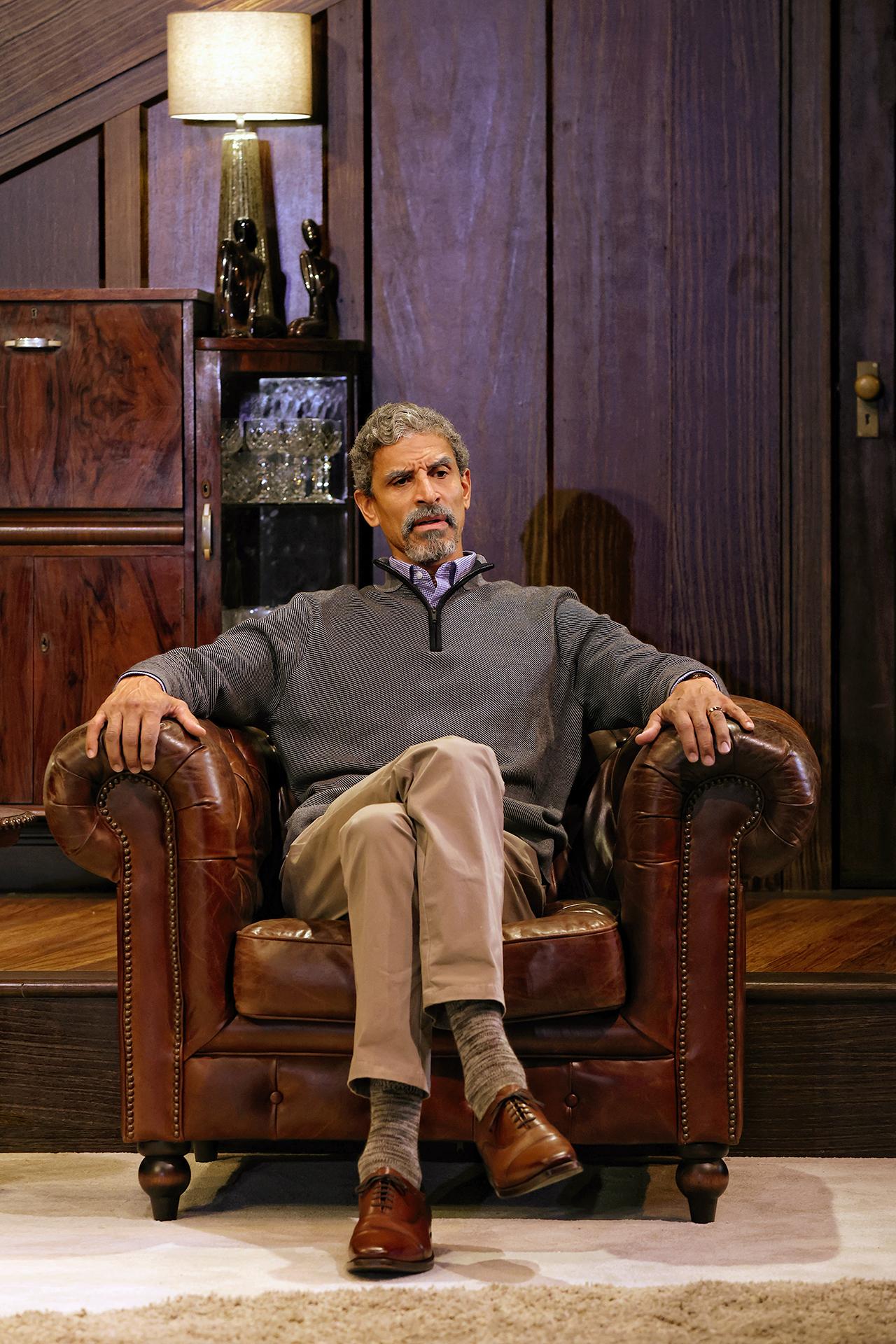

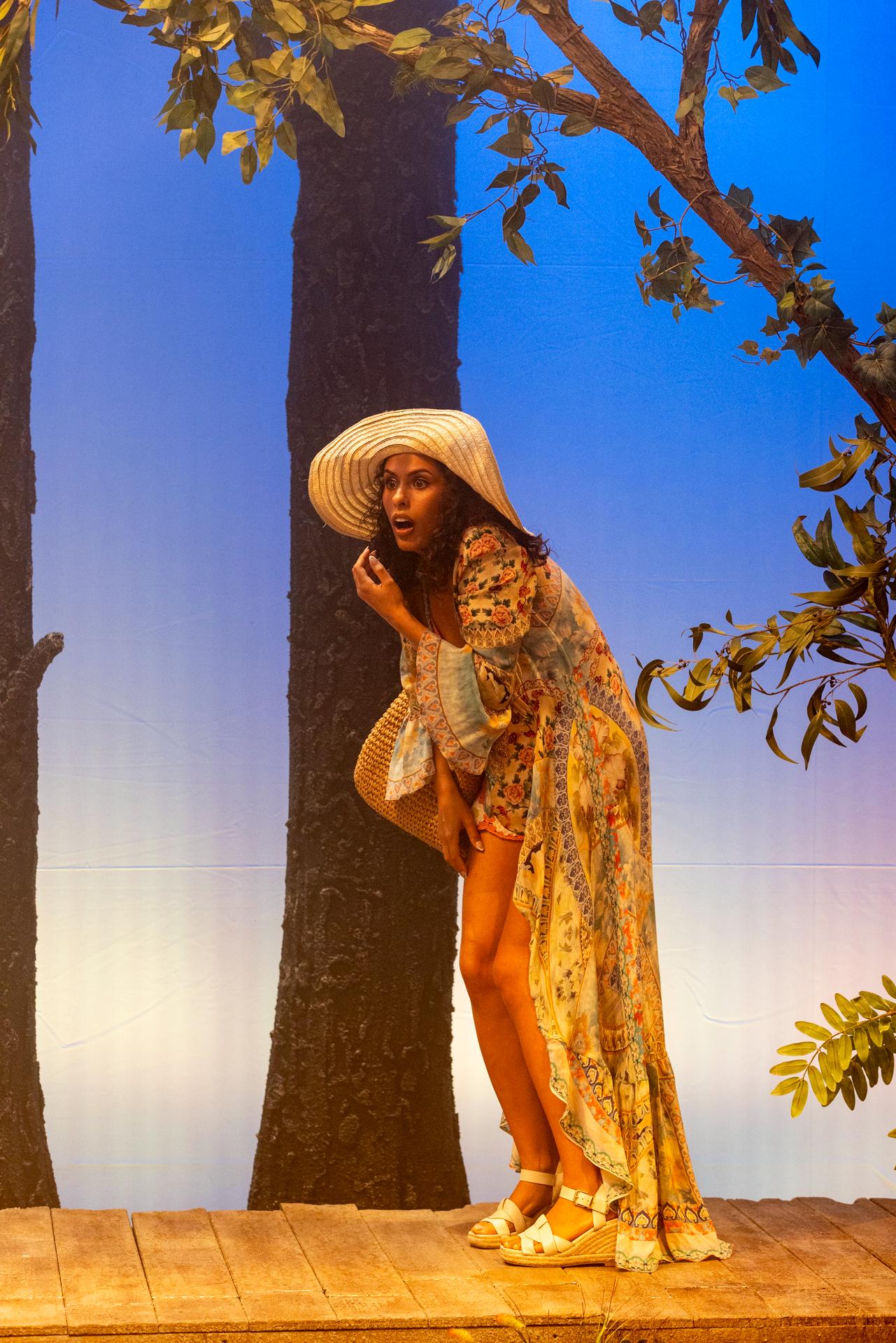

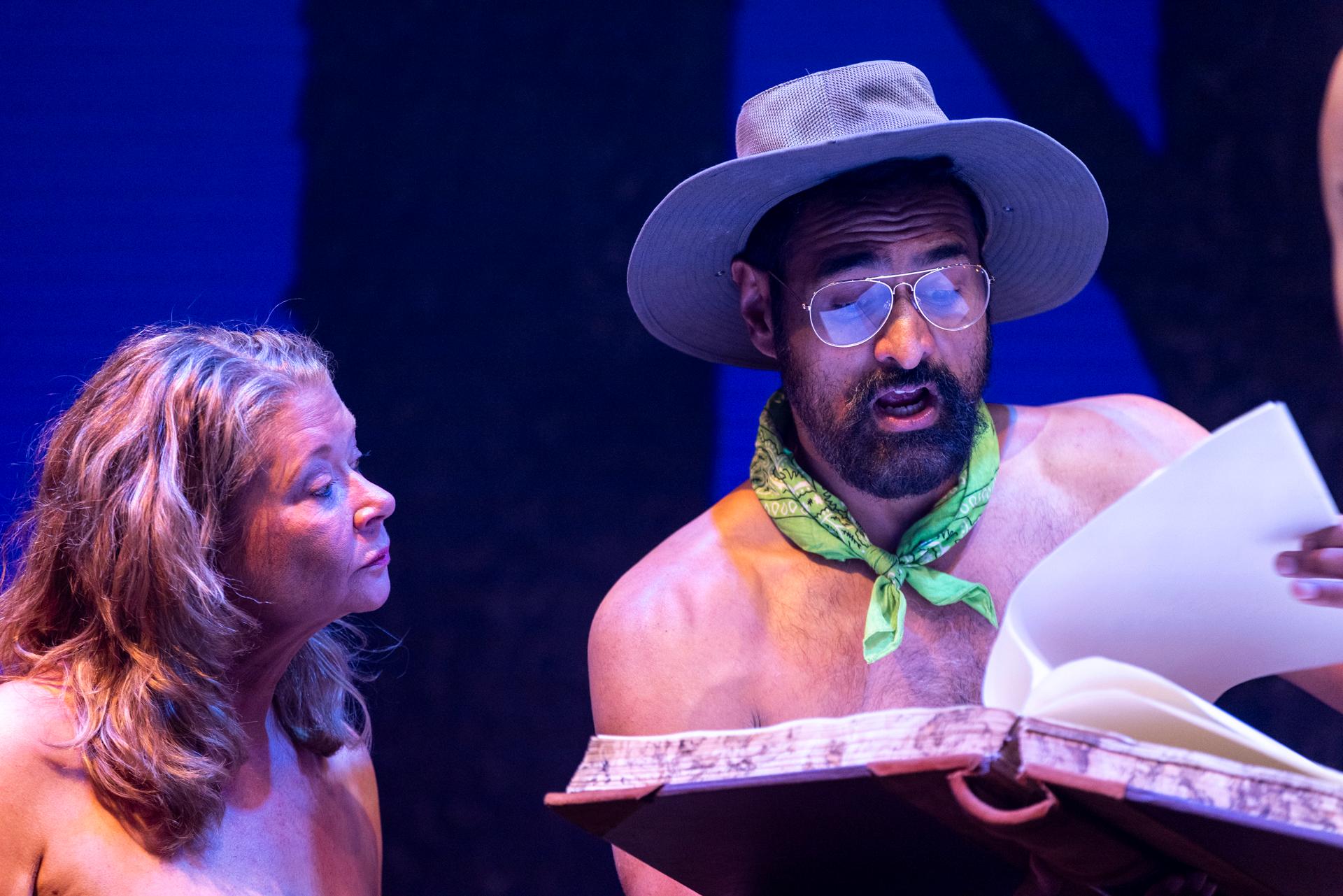

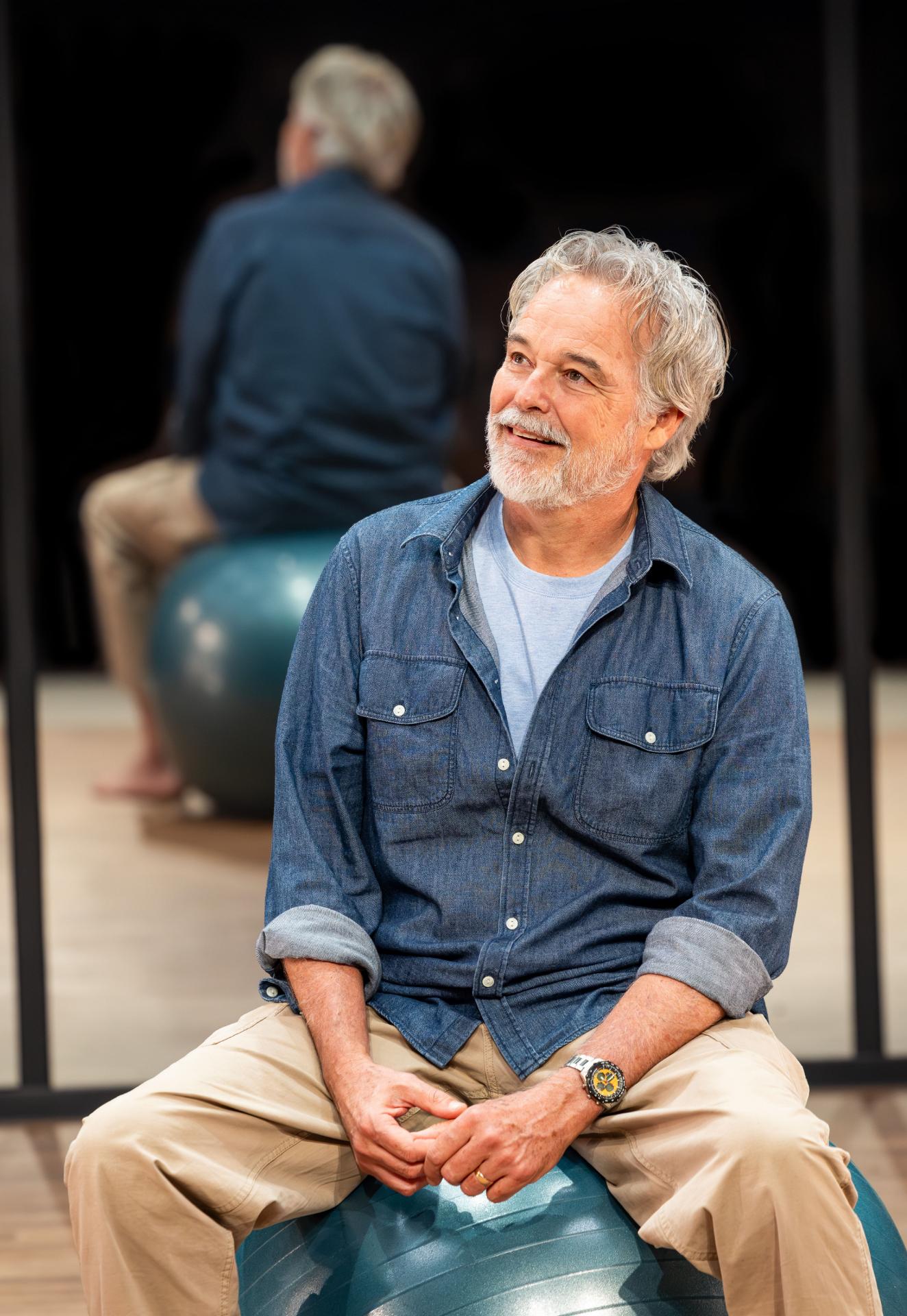

The cast is broadly likeable, if somewhat uneven, with Markus Hamilton leaving the strongest impression, delivering a mesmerisingly profound performance as Solomon. His daughter-in-law Morgan is brought to life by a remarkable Grace Bentley-Tsibuah, who is magnificent in her intensity, inhabiting a role brimming with resentment, rage, and defiance.

Production design by Jeremy Allen creates a Jasper residence that feels suitably traditional and respectable, its windows looking out onto heavy, persistent snowfall that quietly reinforces the play’s sense of place. Lighting by Kelsey Lee shifts in subtle gradations to mirror changes in mood, while consistently flattering and revealing the nuances of each character.

James Peter Brown’s score enters sparingly, transporting us into something more ethereal between the very grounded disputes that form the scintillating emotional core of Purpose. The effect is to create moments of distance and reflection, as though inviting us to consider these deeply human interactions with greater objectivity.

It is natural to have political heroes, but they should serve as sources of inspiration rather than saintly figures upon whom we pin all our hopes and dreams. Solomon may have achieved a great deal in his lifetime, yet we must remember that political projects are never truly complete; they are ongoing, unfinished, and constantly contested.

The systems in which we operate are often made to feel beyond our control, with power appearing distant and elusive. In truth, these structures are bendable and mutable, if only we push harder to exercise our democratic rights and restore faith in the power of collective action — especially in an age marked by the rise of reprehensible authoritarianism and heinous oligarchic influence.