Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Mar 7 – Apr 5, 2026 | Canberra Theatre Centre, Apr 10 – 18, 2026 | Arts Centre Melbourne, Apr 23 – May 10, 2026

Playwright: William Shakespeare

Director: Peter Evans

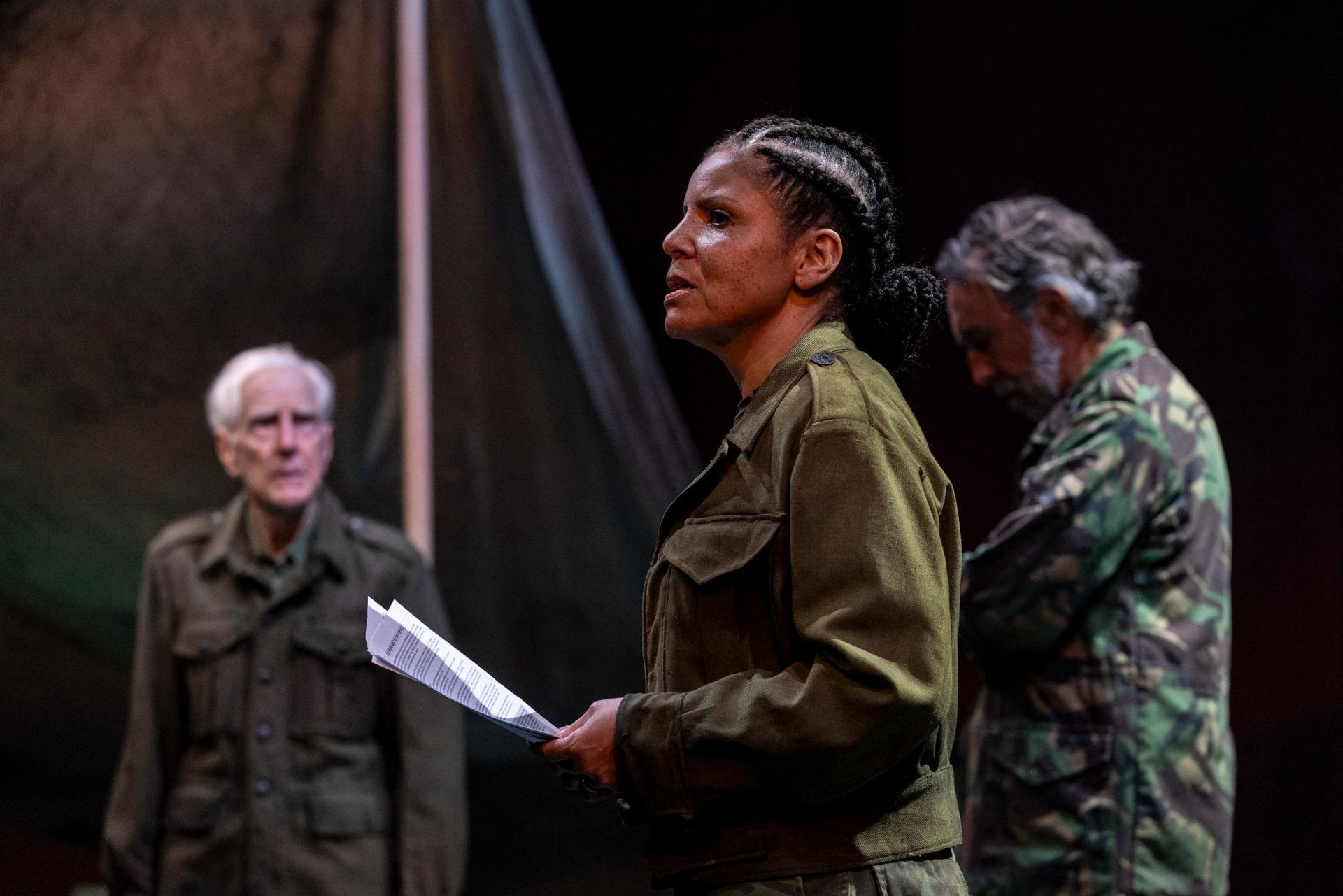

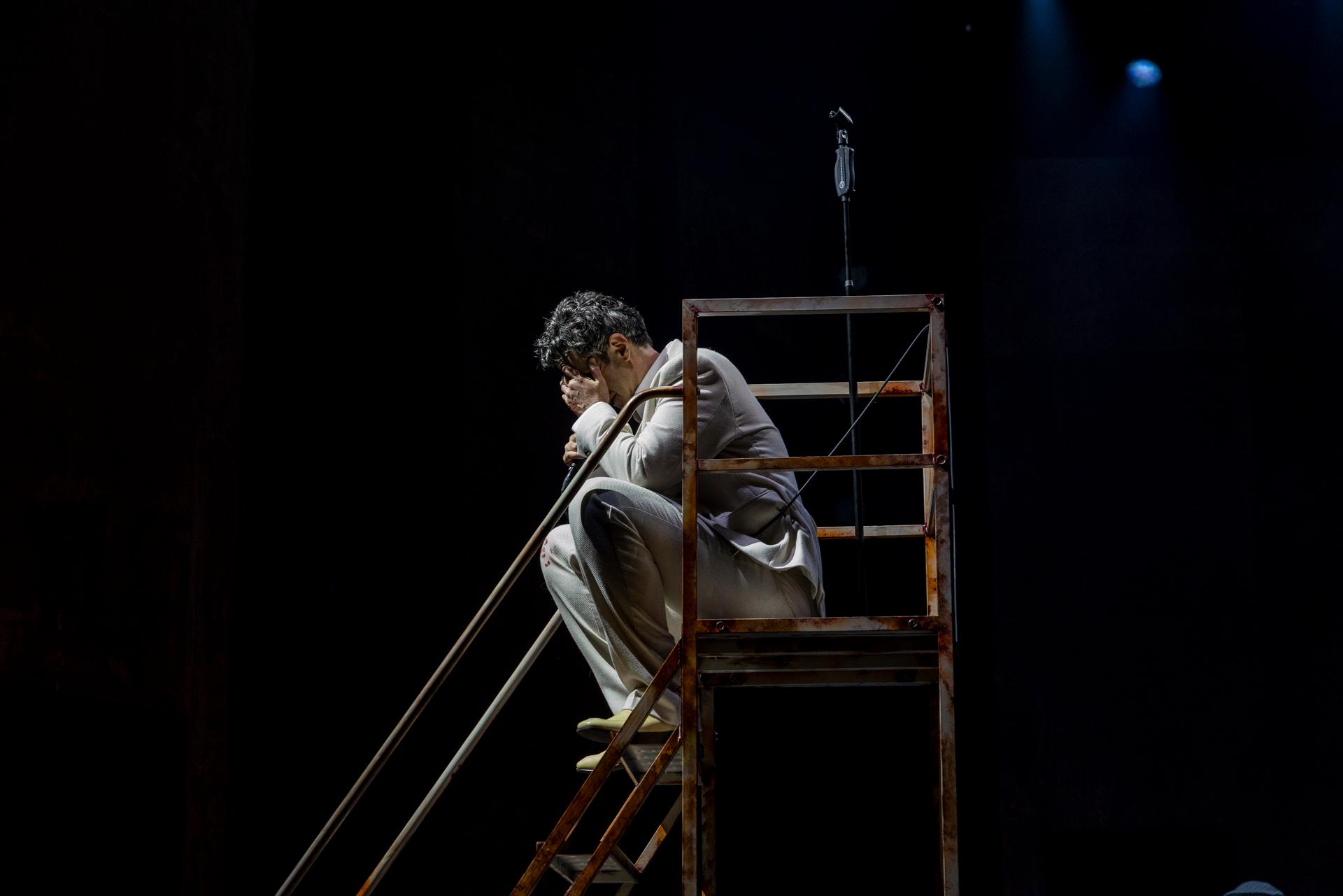

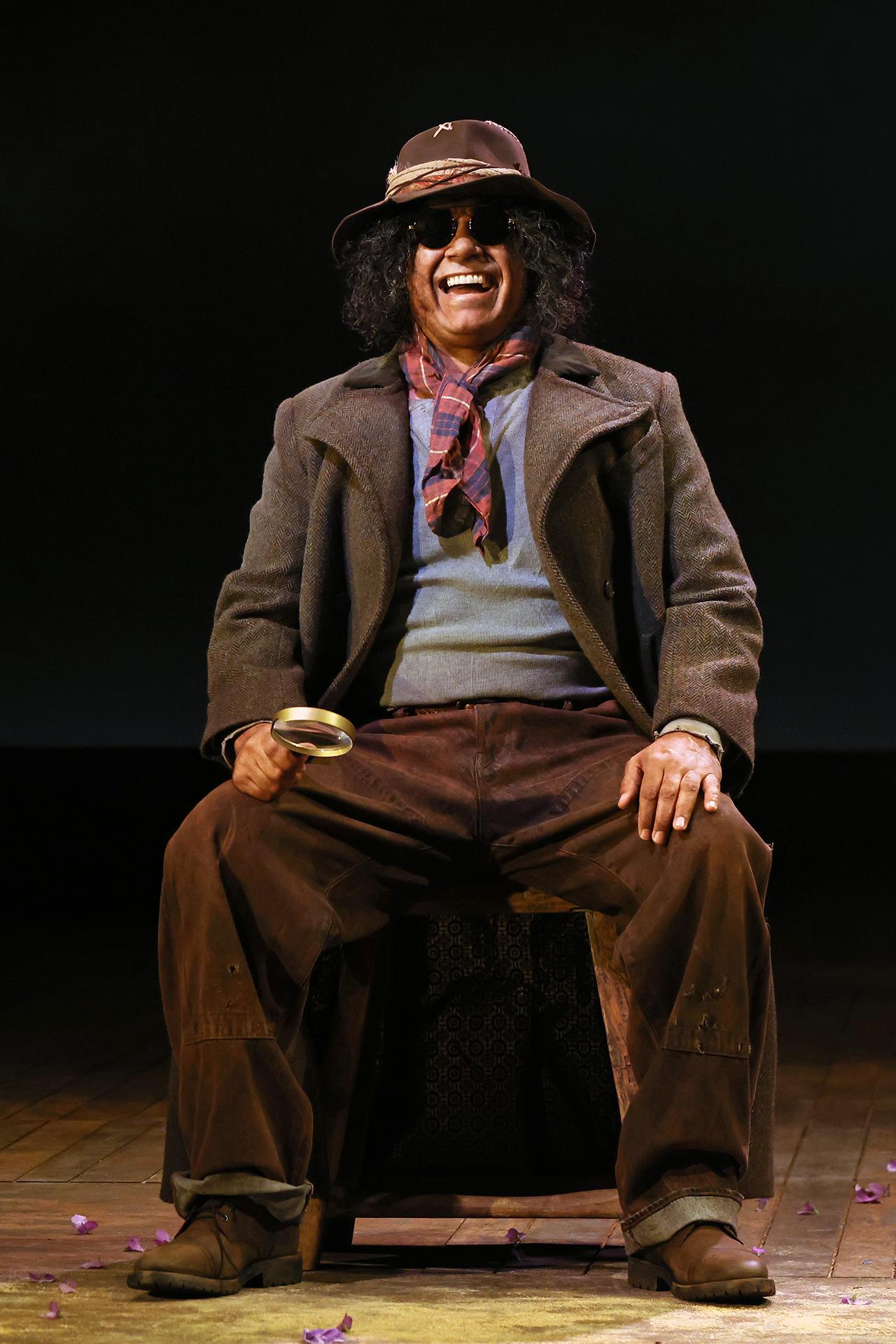

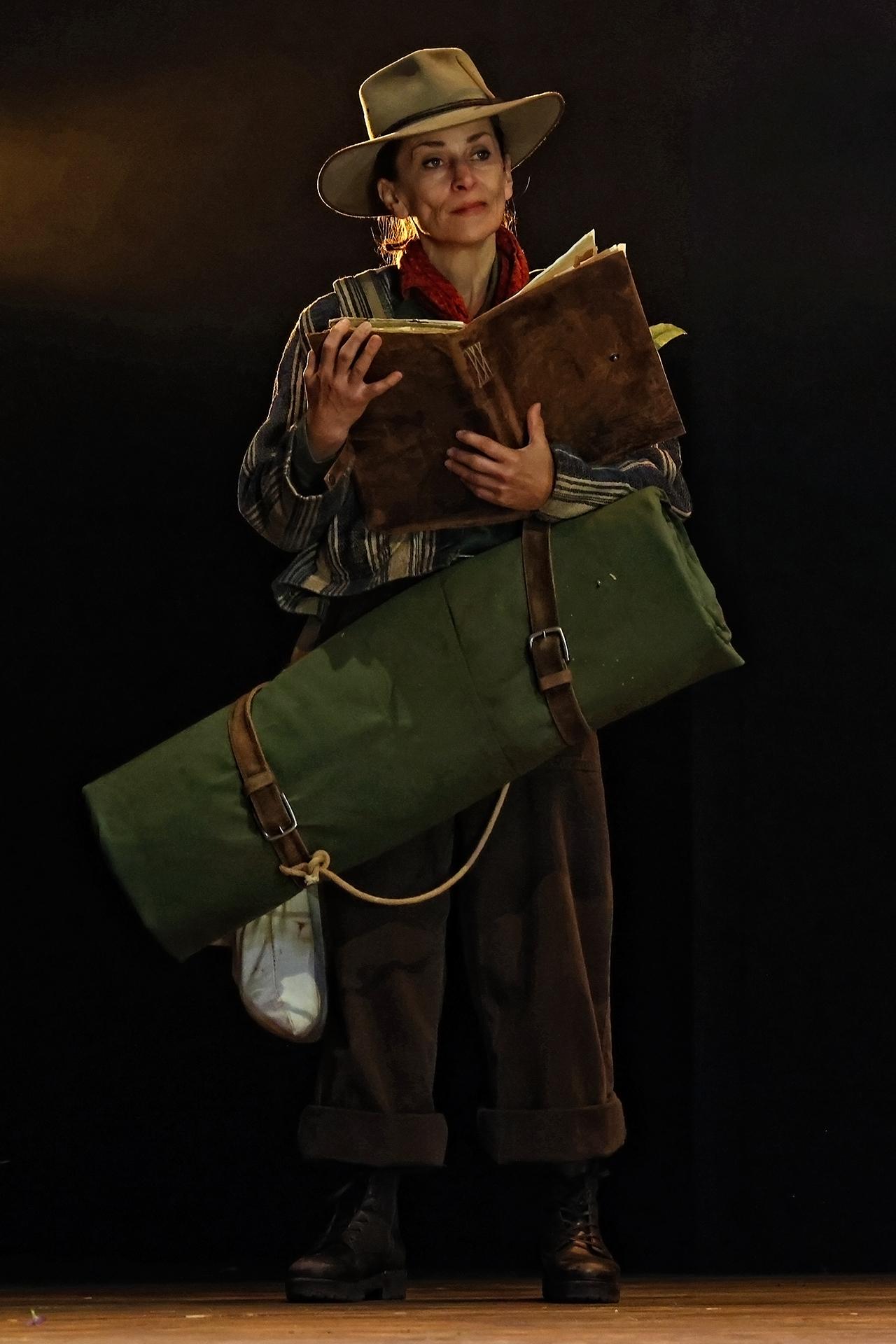

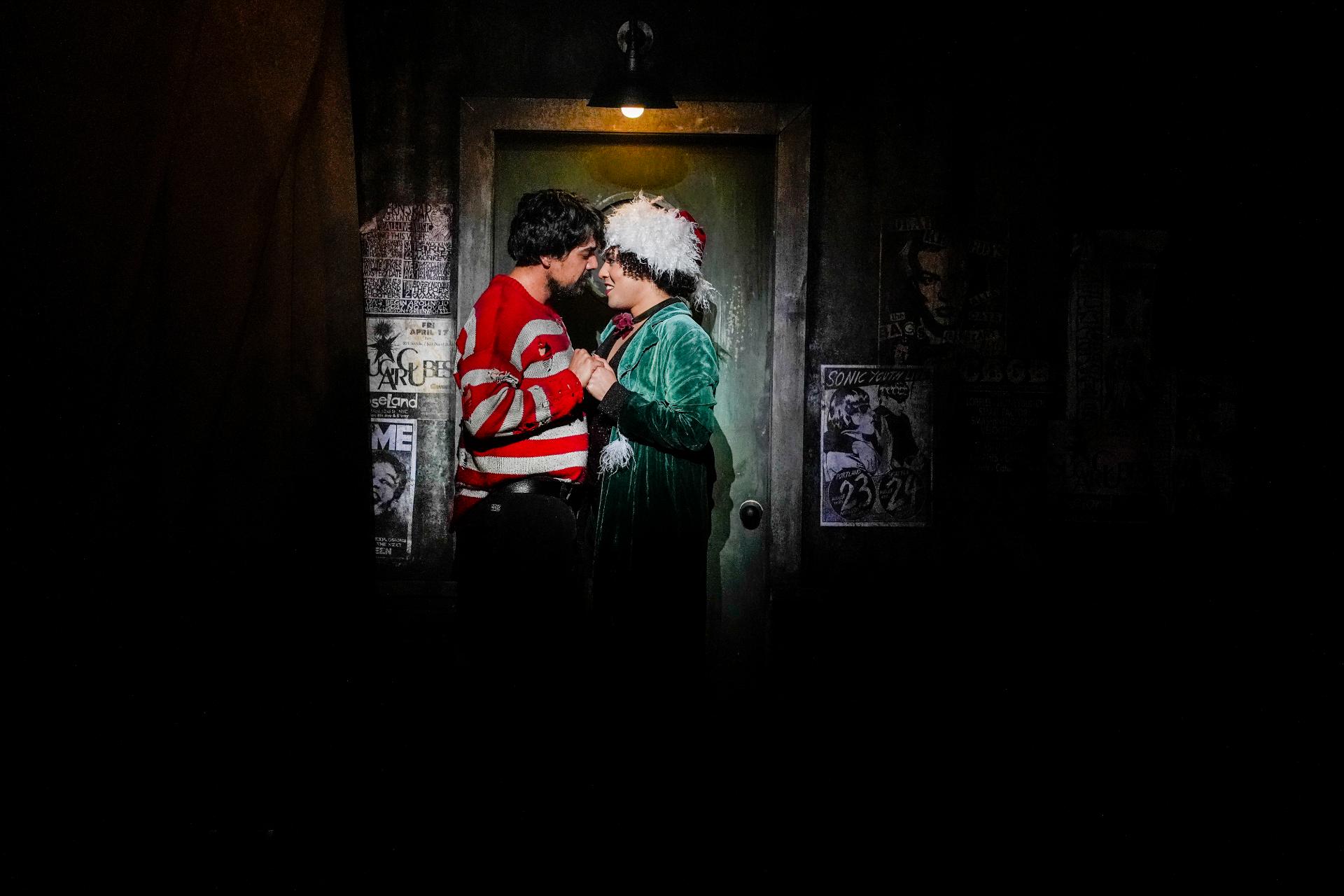

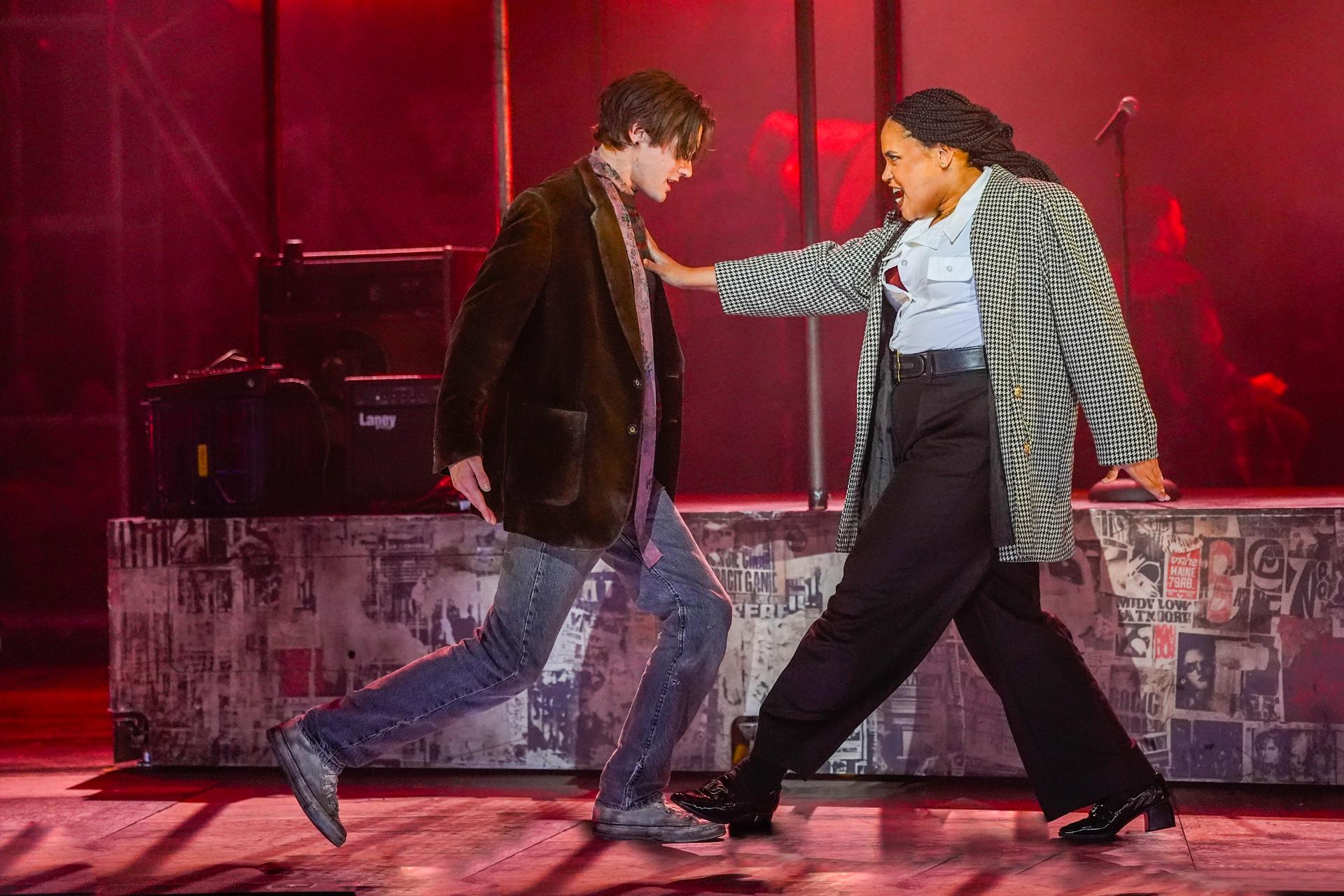

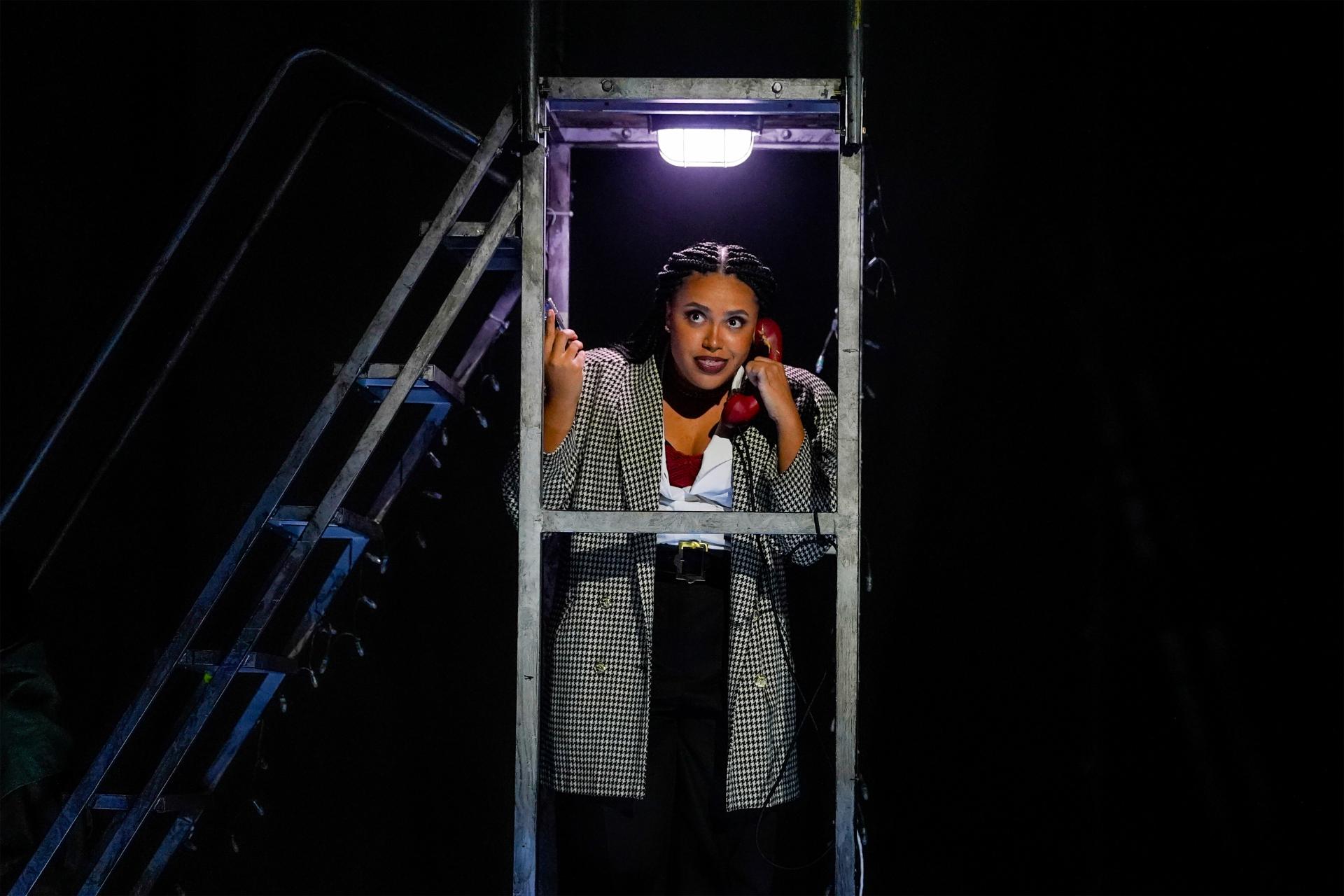

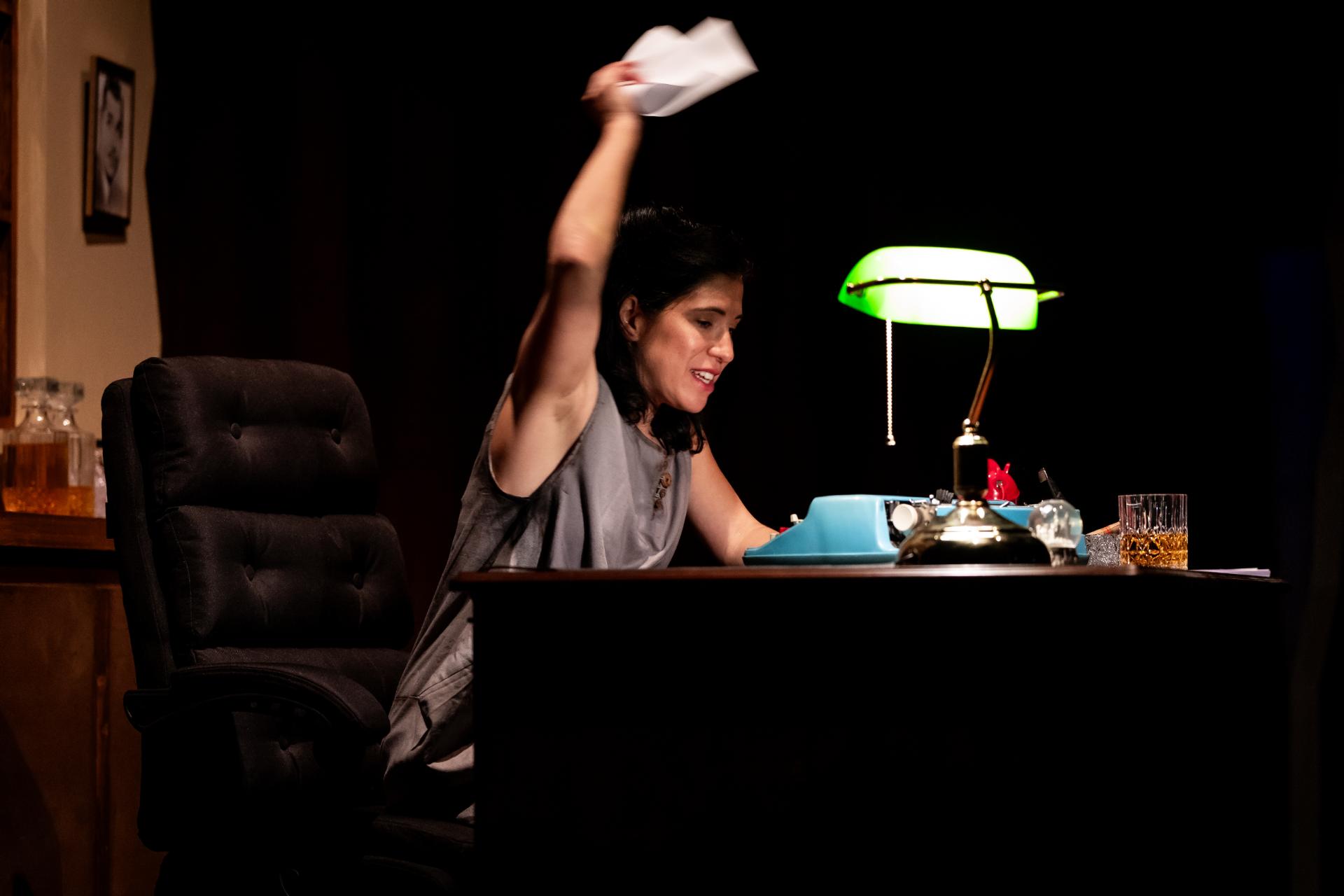

Cast: Jules Billington, Peter Carroll, Septimus Caton, Ray Chong Nee, Leon Ford, Mark Leonard, James Lugton, Ava Madon, Ruby Maishman, Brigid Zengeni

Images by Brett Boardman

Theatre review

It is a testament to the unsettling prescience of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar” that it resonates with such urgency today. In an era marked by the rise of authoritarian figures across the globe—from the United States to West Asia, and from Russia to Africa—the play gives dramatic form to a pervasive and dangerous fantasy: the assassination of a monstrous leader. Yet the true sophistication of the work lies not in its depiction of the killing, but in its unflinching interrogation of the aftermath. It indulges our visceral desire for a tyrant’s fall, only to force us to confront the sobering question of what comes next.

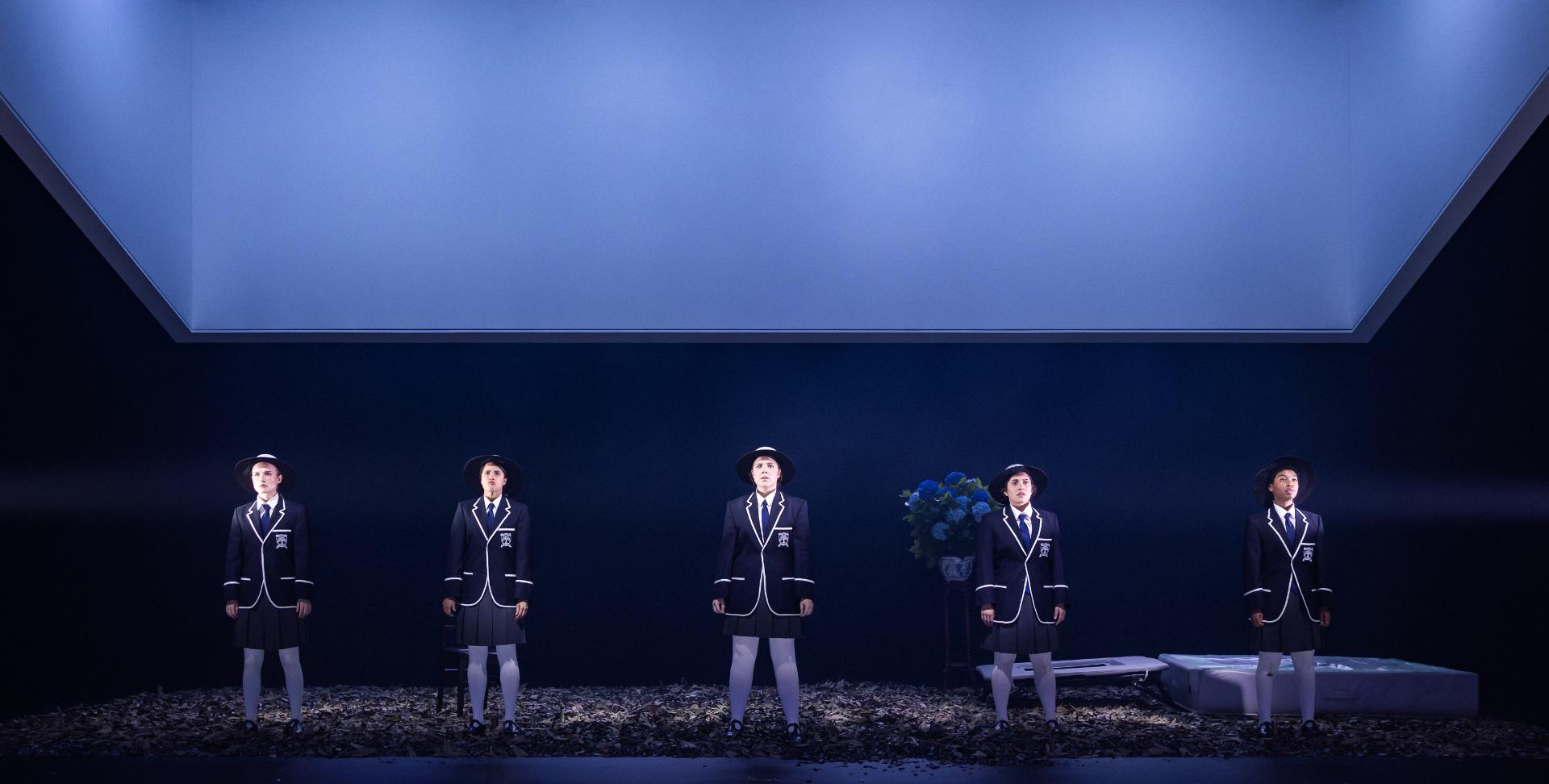

Perhaps it is a testament to the enduring power of Shakespeare’s narrative that director Peter Evans approaches the material with such restrained deference, seemingly content to let the text speak for itself. While one might wish for a staging with greater interpretative audacity—something to jolt the senses and cater to the abbreviated attention spans that define the 21st-century spectator—the production ultimately finds its strength in a kind of quiet integrity. It resists the temptation to embellish, trusting instead in the story’s inherent moral gravity. The result, though at times dramatically inert and emotionally remote, nevertheless ensures that the play’s central thesis lands with unadorned clarity.

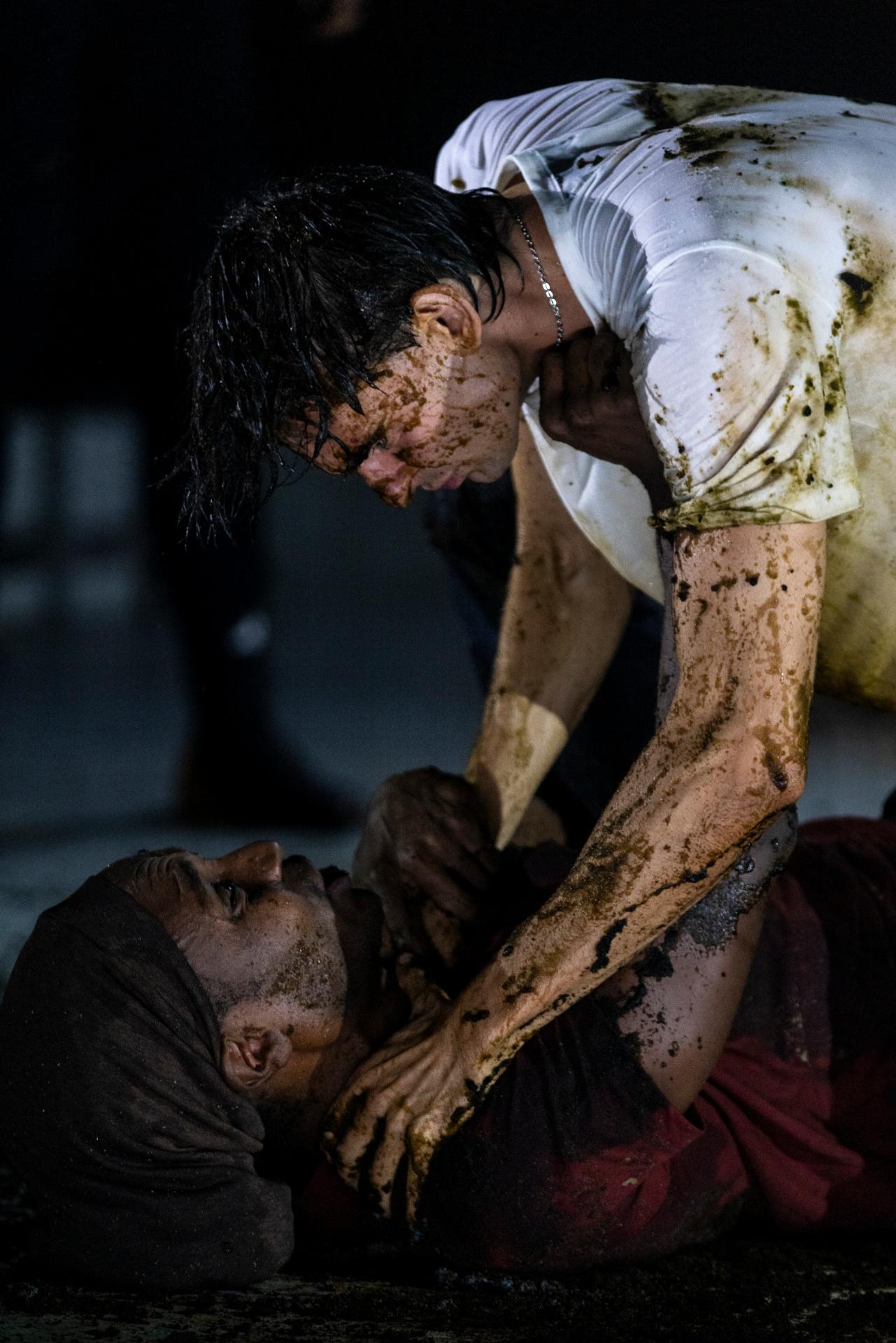

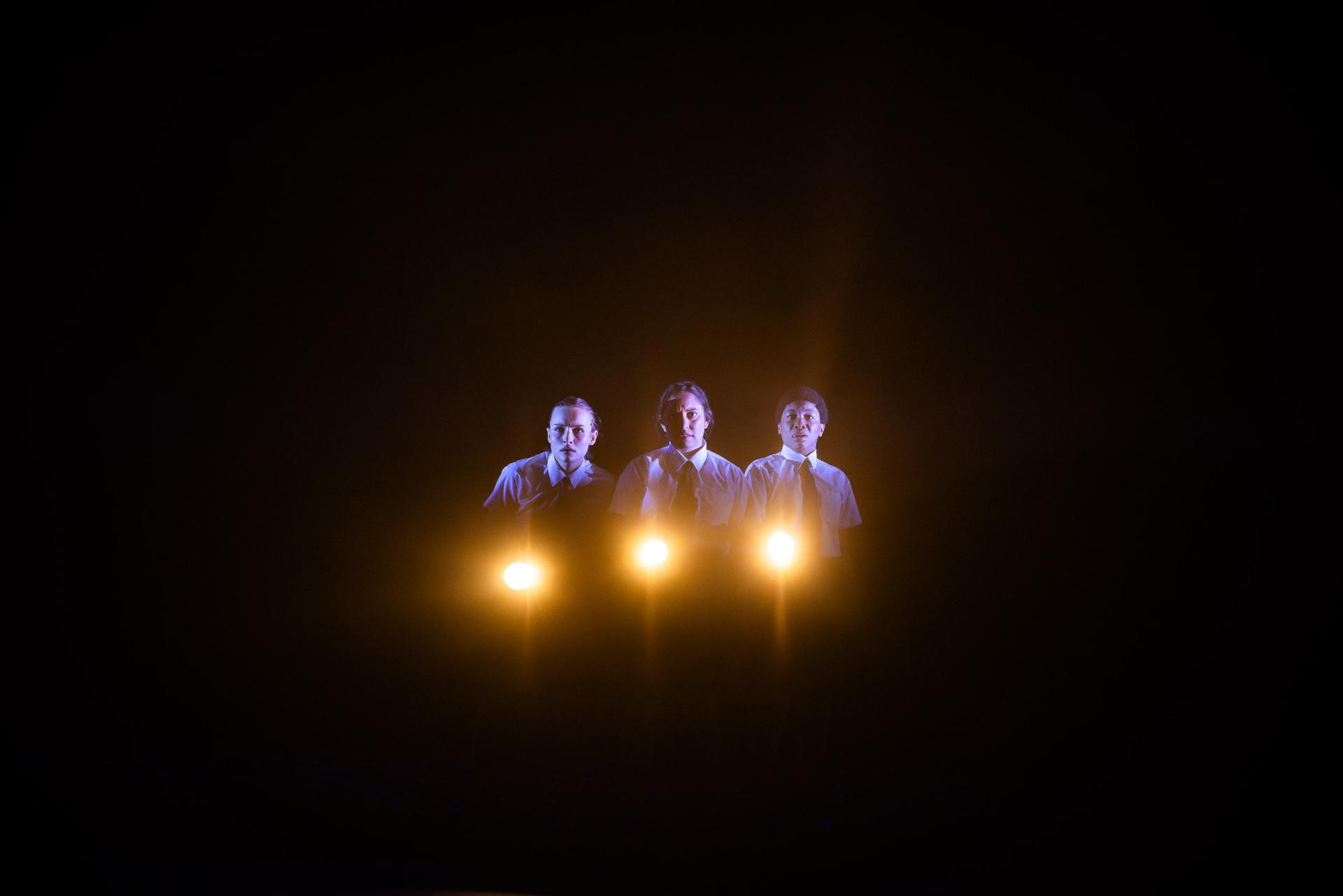

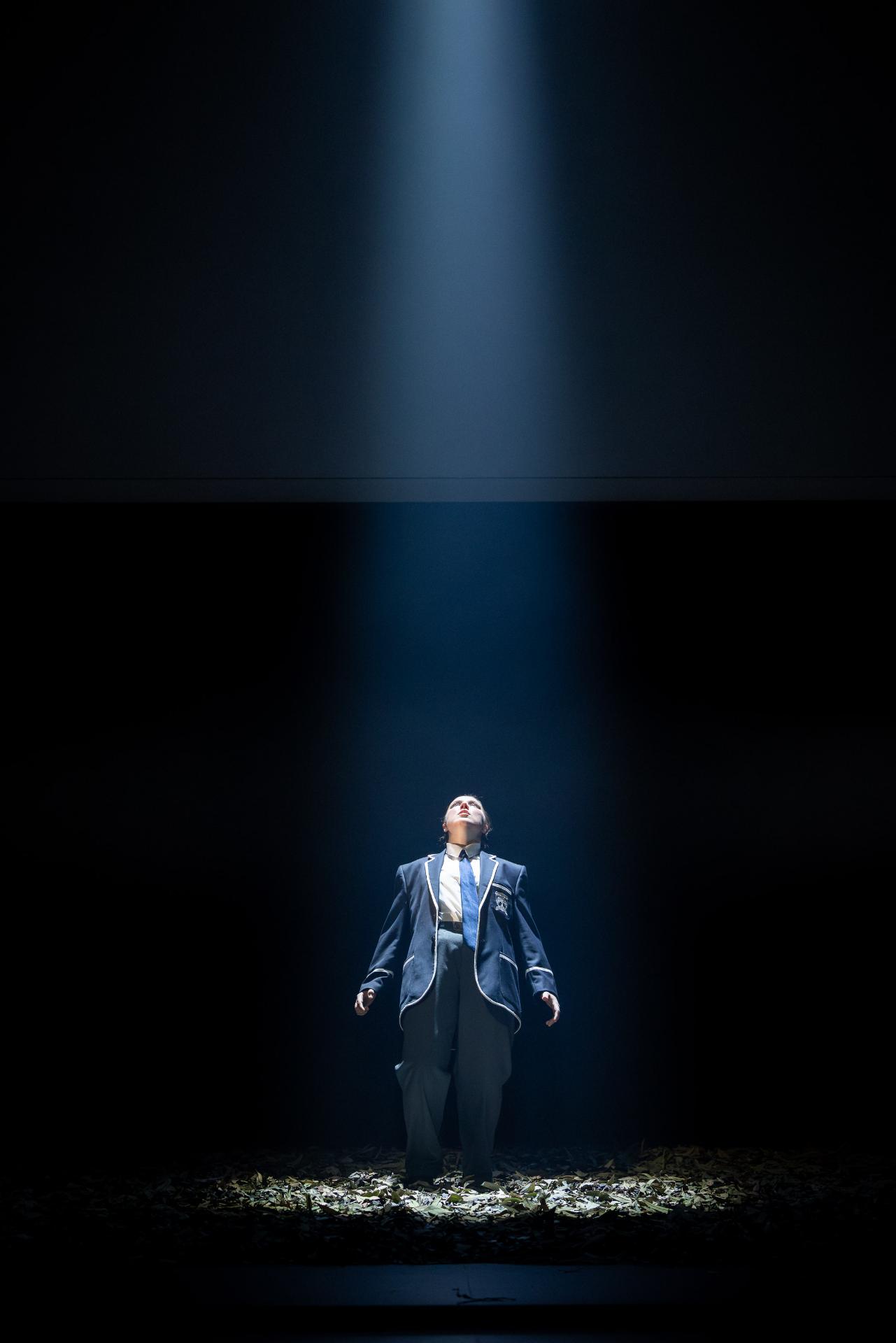

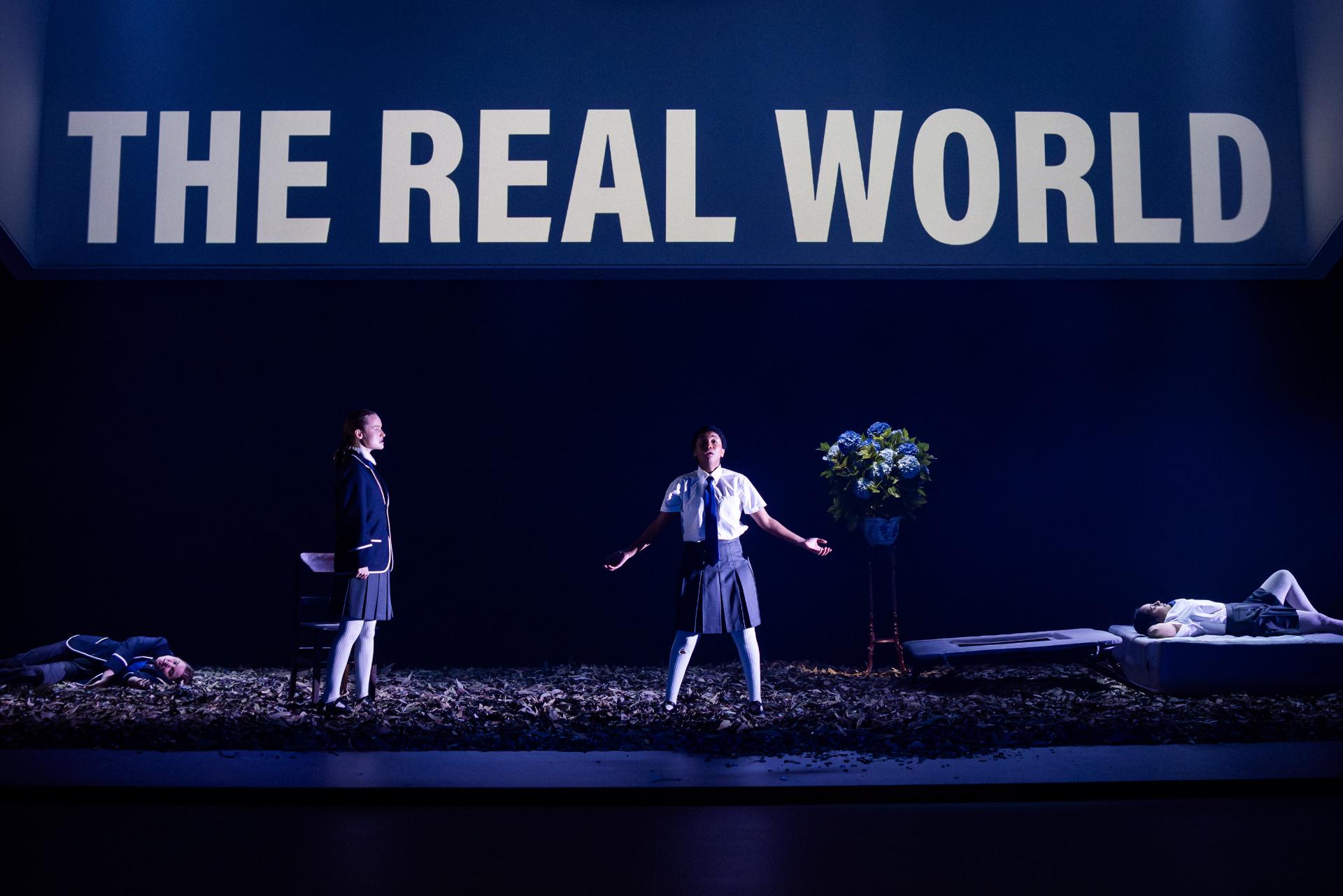

Amelia Lever-Davidson’s lighting design and Madeleine Picard’s sonic composition each begin with subtlety, only to swell into heightened theatricality as the production careens toward its conclusion—a gradual unshackling of atmosphere that mirrors the play’s unravelling order. Simone Romaniuk’s costumes chart a more subtle arc of descent: pristine shades of white give way to the muted austerity of military fatigues, signalling a visual erosion of civility. All of this unfolds against Peter Evans’ scenography, which is marked by a carefully calibrated functionality—spare, yet not without its own quiet appeal.

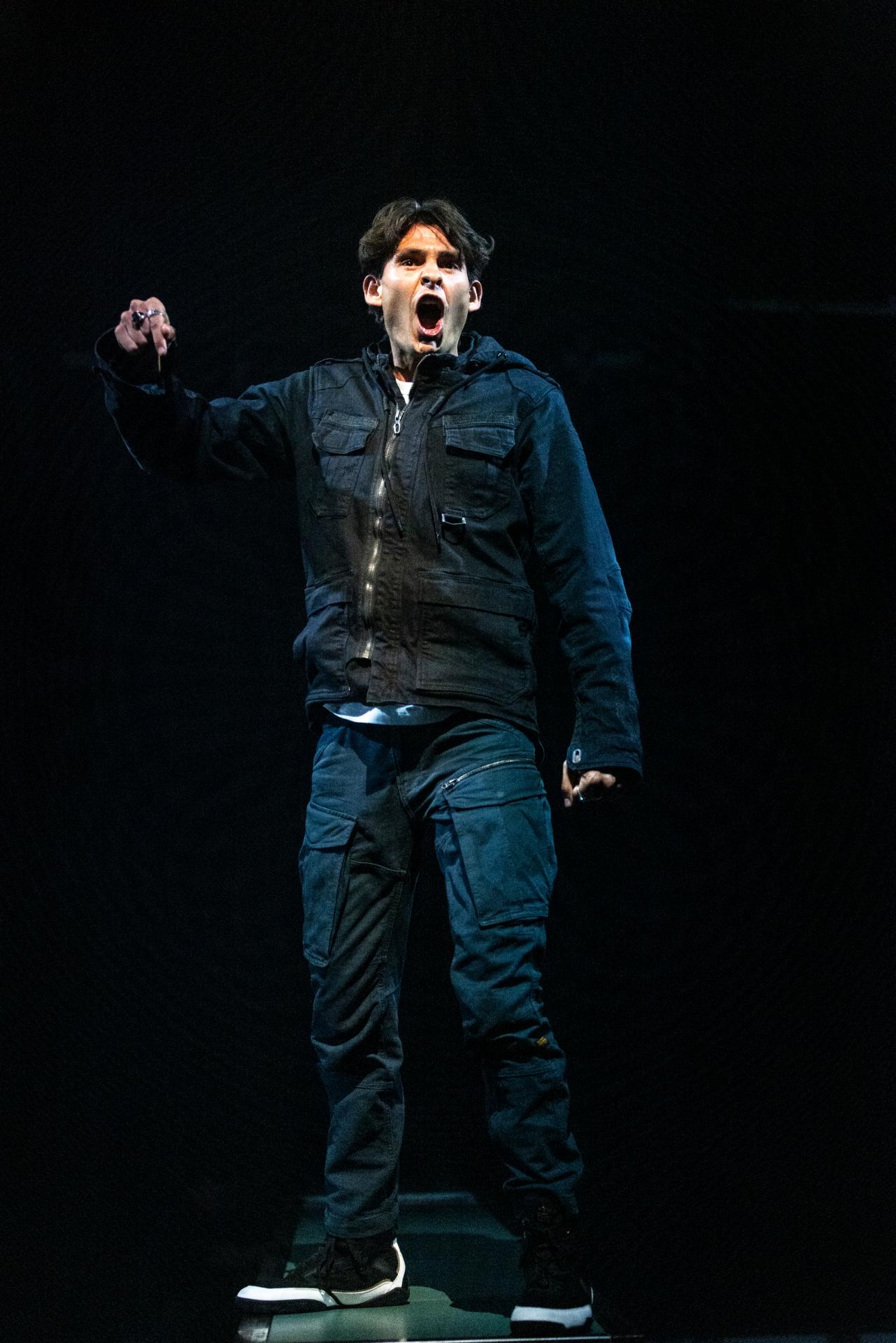

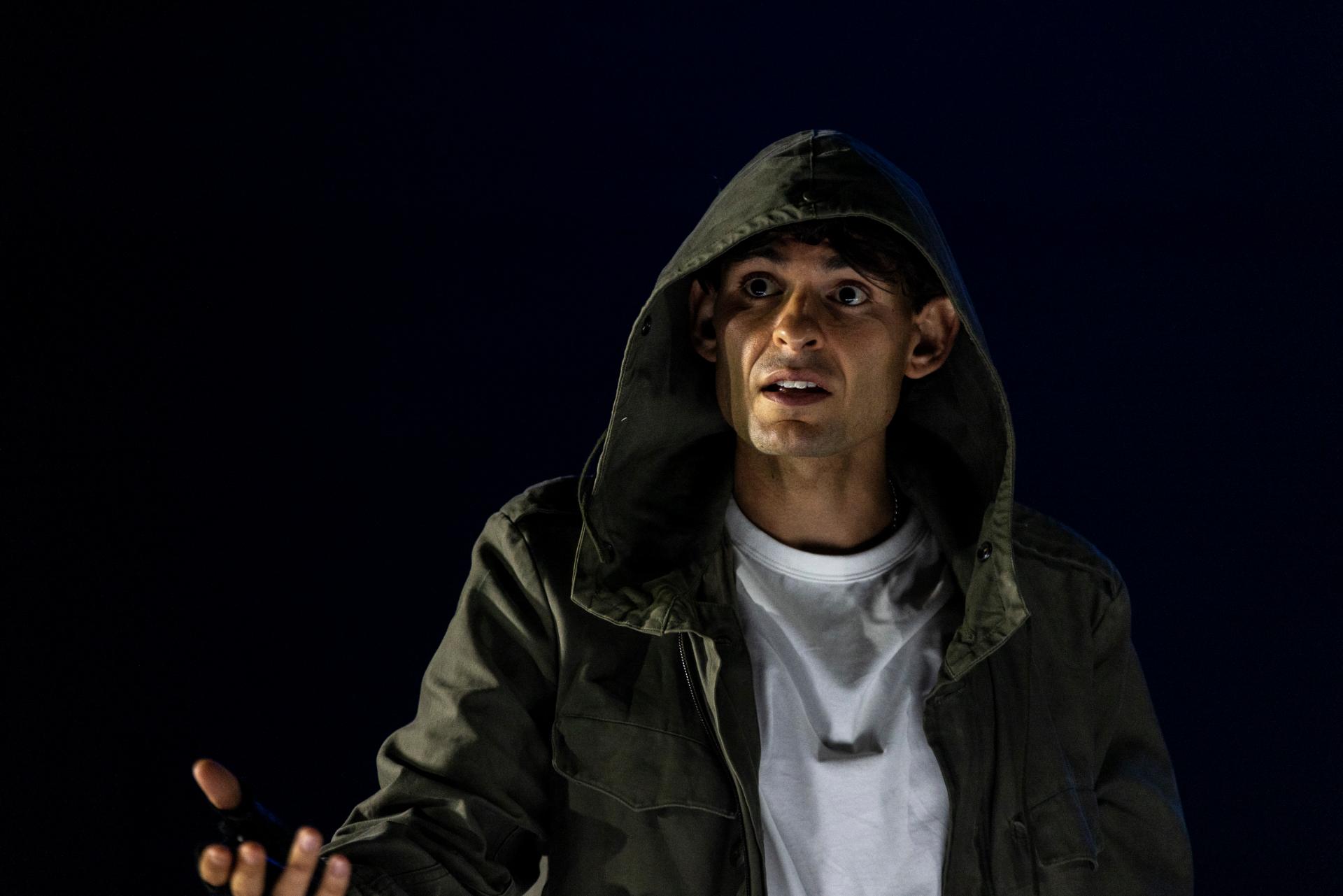

Leon Ford’s Cassius and Brigid Zengeni’s Brutus anchor the production with a taut, combustible intensity, their charged exchanges lending the drama an urgent, propulsive rhythm. Yet it is Mark Leonard Winter who emerges as the production’s most indelible presence. His Mark Antony is a study in delicious flamboyance—magnetic, audacious, and unsettlingly modern. In his hands, the role acquires a dramatic sensibility that feels both distinctly contemporary and strangely singular, drawing us into the gravitational pull of a performance that refuses to be forgotten.

It is entirely understandable—perhaps even inevitable—that we indulge in fantasies of political assassination, so relentlessly are we barraged with images of despots and the devastation they wreak across continents. Yet we must not lose sight of a more sobering truth: these figures did not materialize from the ether. They ascended through systems meticulously engineered for their rise, buoyed by social forces that will persist, unperturbed, long after their removal. Decapitate the serpent, and the body slithers on.