Venue: Ensemble Theatre (Kirribilli NSW), Jan 4 – Feb 8, 2020 | Riverside Theatres (Parramatta NSW), Feb 18 – 22, 2020

Venue: Ensemble Theatre (Kirribilli NSW), Jan 4 – Feb 8, 2020 | Riverside Theatres (Parramatta NSW), Feb 18 – 22, 2020

Playwright: Geoffrey Atherden

Director: Wesley Enoch

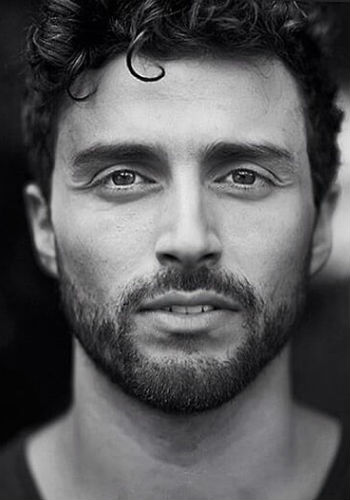

Cast: Joseph Althouse, Luke Carroll, Chenoa Deemal, Aaron McGrath, Colin Smith, Dubs Yunupingu

Images by Prudence Upton

Theatre review

When Johnny ‘Unaarrimin’ Mullagh went to England in 1868 as part of Australia’s ‘First XI’, he probably never expected to become our first international cricket star. A century and a half later, his descendants probably never expected that the legend would today be so easily forgotten. Black Cockatoo by Geoffrey Atherden reintroduces the historical figure as a true Indigenous trailblazer, an Aboriginal example of black excellence that the white patriarchy of our sporting arenas seems so determined to wipe away from memory. The play has a tendency to feel overly wholesome, as though sanitised for public consumption, but its importance as cultural emblem cannot be understated.

Directed by Wesley Enoch, the show is a sincere and tender proclamation, paying tribute to Indigenous identities past and present. The complexity of black experiences as colonised peoples, is meaningfully, albeit politely, portrayed in Black Cockatoo. We see our protagonist in a state of conflict, able to recognise his privilege as star on the field, but never ignorant of injustices that befall himself and those he considers his community.

Set design by Richard Roberts establishes elegance for the production’s overall visual aesthetic, but requires greater versatility to help us imagine dramatic shifts in time and place. Lights by Trent Suidgeest and music by Steve Francis are sensitively rendered, both proving effective in conveying poignancy for the piece.

Actor Aaron McGrath is full of charm as Mullagh, dignified and beautifully nuanced in his depiction of a true blue hero. Black Cockatoo‘s narrative does not offer very much that is emotional or surprising, but McGrath makes us fall for the central character effortlessly. In the role of Lady Bardwell is the noteworthy Chenoa Deemal, who brings to the stage an august presence. Also impressive is Colin Smith as coach of the team, remarkably convincing as an ethically dubious Charles Lawrence.

Our Indigenous continue to have to navigate the absurdity of being seen as exotic on their own land. The ‘First XI’ went to England to play cricket, but often found themselves perceived as a circus act, a curiosity that robbed them of their humanity, a persisting strategy that provides legitimacy to mistreatment at the hands of colonisers. We need to hear the voices of minorities, because an understanding of their autonomy is fundamental to the betterment of all our lives. We no longer want our stories told by others. We want the right to talk about ourselves, whether or not the others are willing to listen.

Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Jan 23 – 27, 2019

Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Jan 23 – 27, 2019

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Jan 23 – 26, 2019 | Dunstan Playhouse (Adelaide Festival Centre, South Australia), Mar 8 – 11, 2019

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Jan 23 – 26, 2019 | Dunstan Playhouse (Adelaide Festival Centre, South Australia), Mar 8 – 11, 2019

Venue: Carriageworks (Eveleigh NSW), Jan 18 – 23, 2019

Venue: Carriageworks (Eveleigh NSW), Jan 18 – 23, 2019

Venue: Carriageworks (Eveleigh NSW), Jan 16 – 20, 2019

Venue: Carriageworks (Eveleigh NSW), Jan 16 – 20, 2019

Venue: Sydney Town Hall (Sydney NSW), Jan 11 – Feb 2, 2019 | Ridley Centre (Adelaide Showgrounds, South Australia) Mar 2 – 9, 2019

Venue: Sydney Town Hall (Sydney NSW), Jan 11 – Feb 2, 2019 | Ridley Centre (Adelaide Showgrounds, South Australia) Mar 2 – 9, 2019

Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Jan 19 – Feb 4, 2018

Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Jan 19 – Feb 4, 2018 Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Jan 5 – 21, 2018

Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Jan 5 – 21, 2018