Venue: Carriageworks (Eveleigh NSW), Jan 10 – 15, 2026

Playwright: Daley Rangi

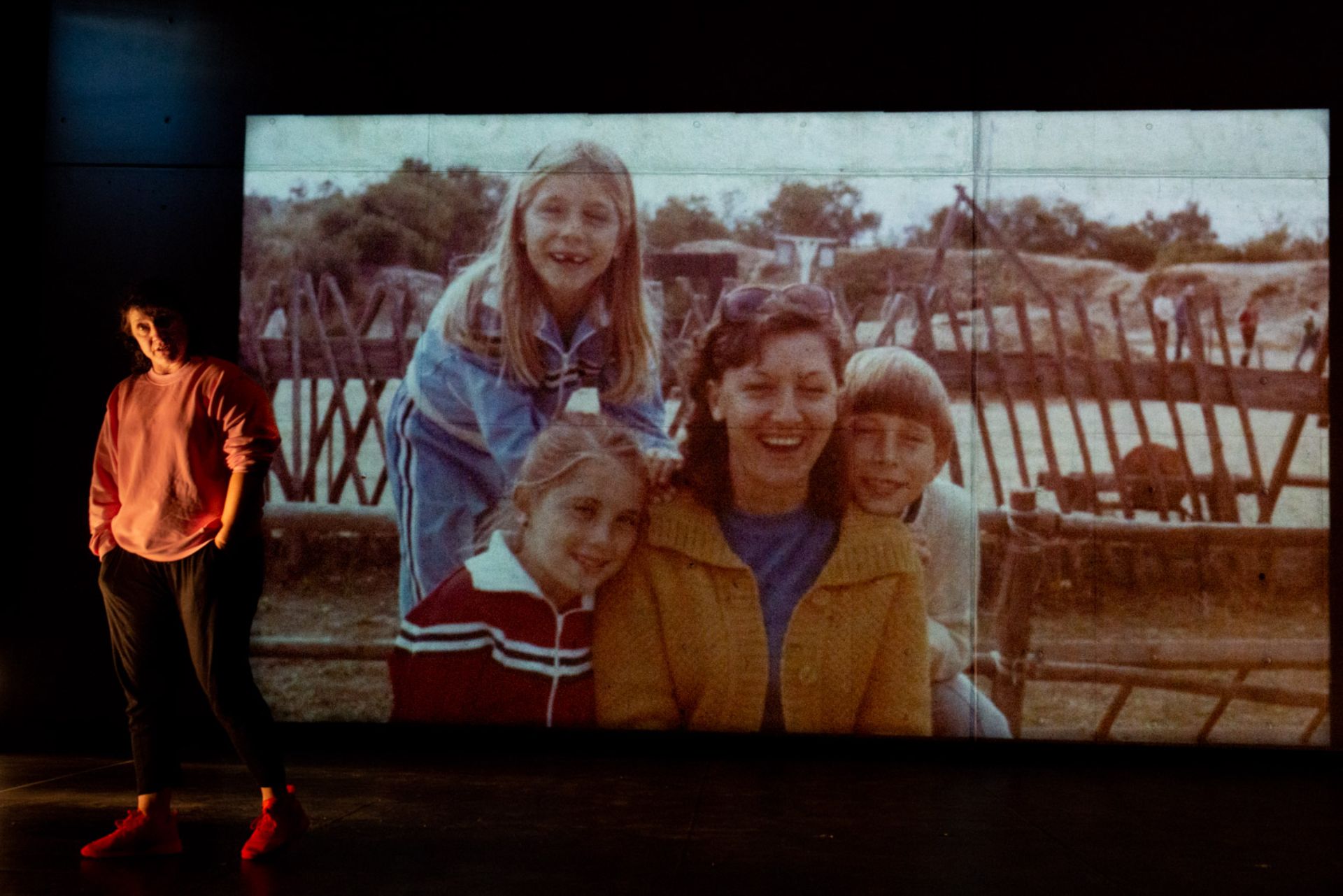

Cast: Daley Rangi

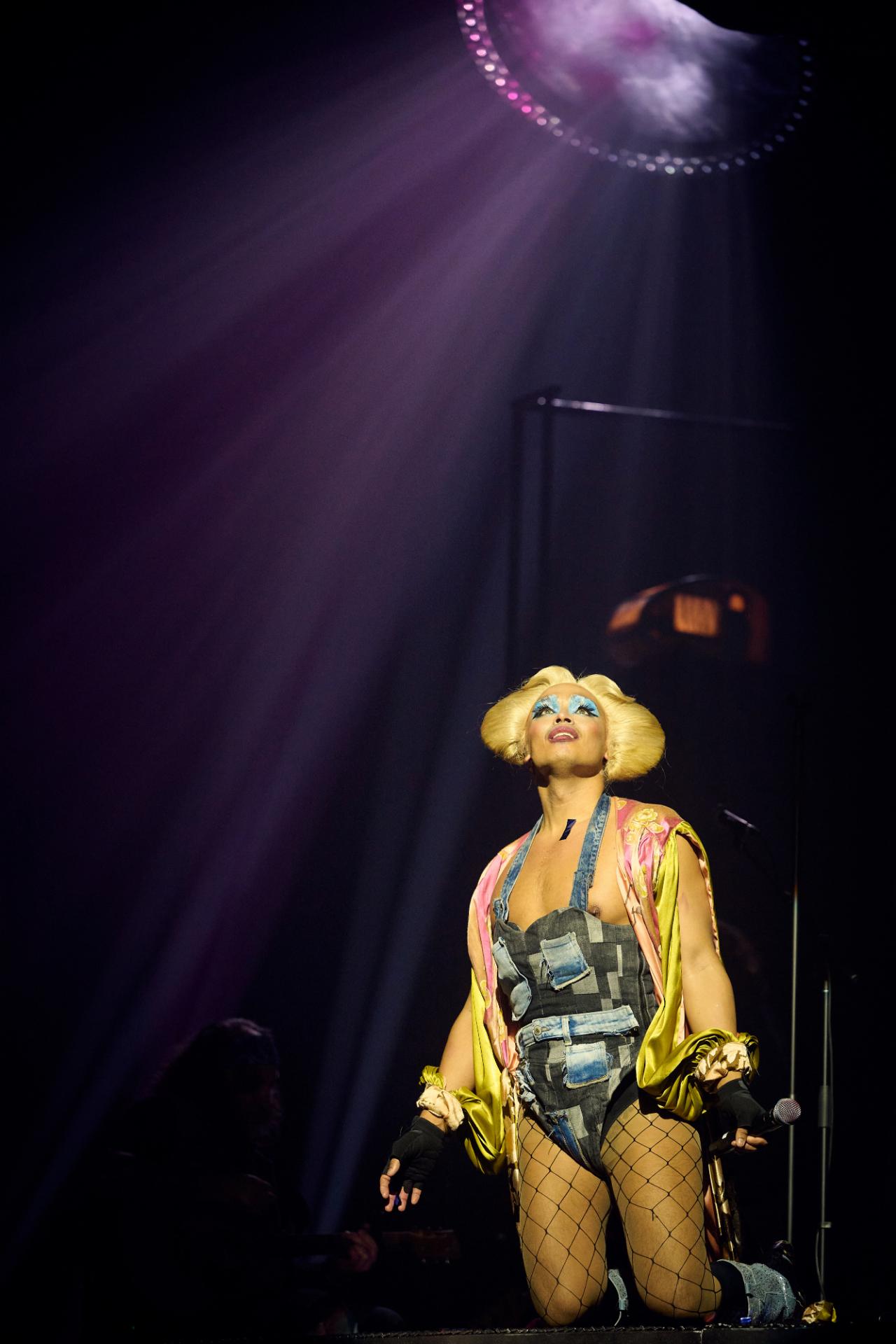

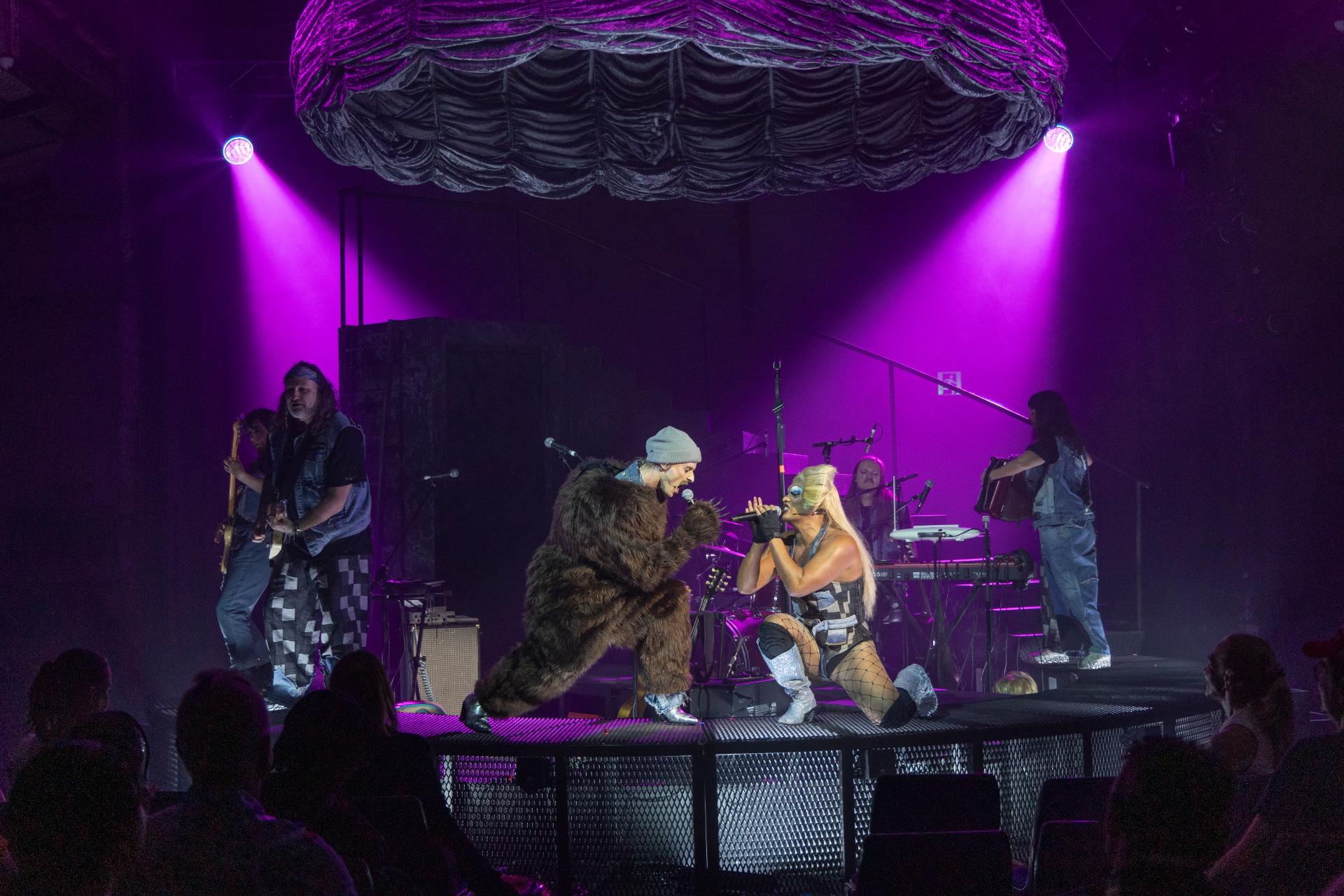

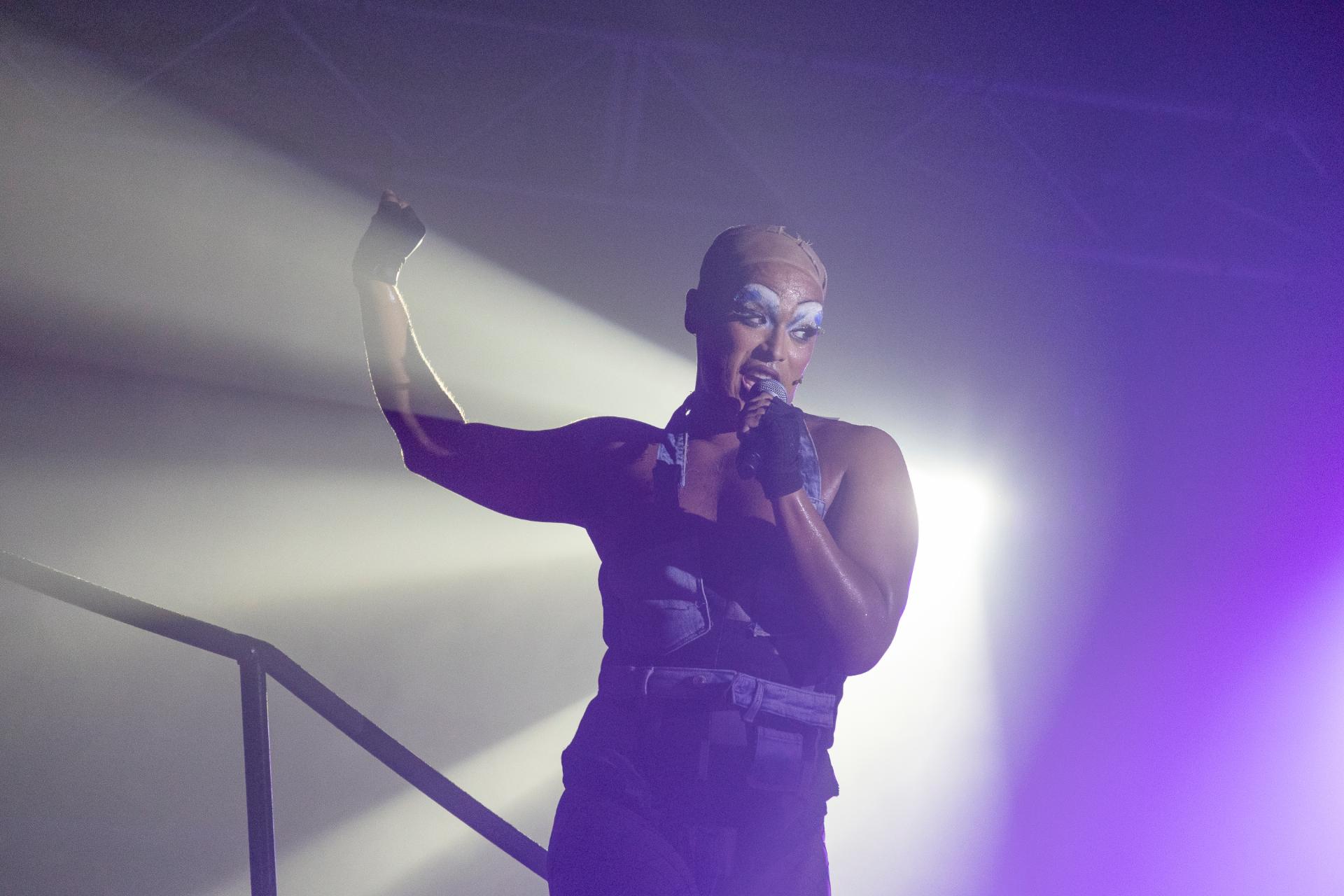

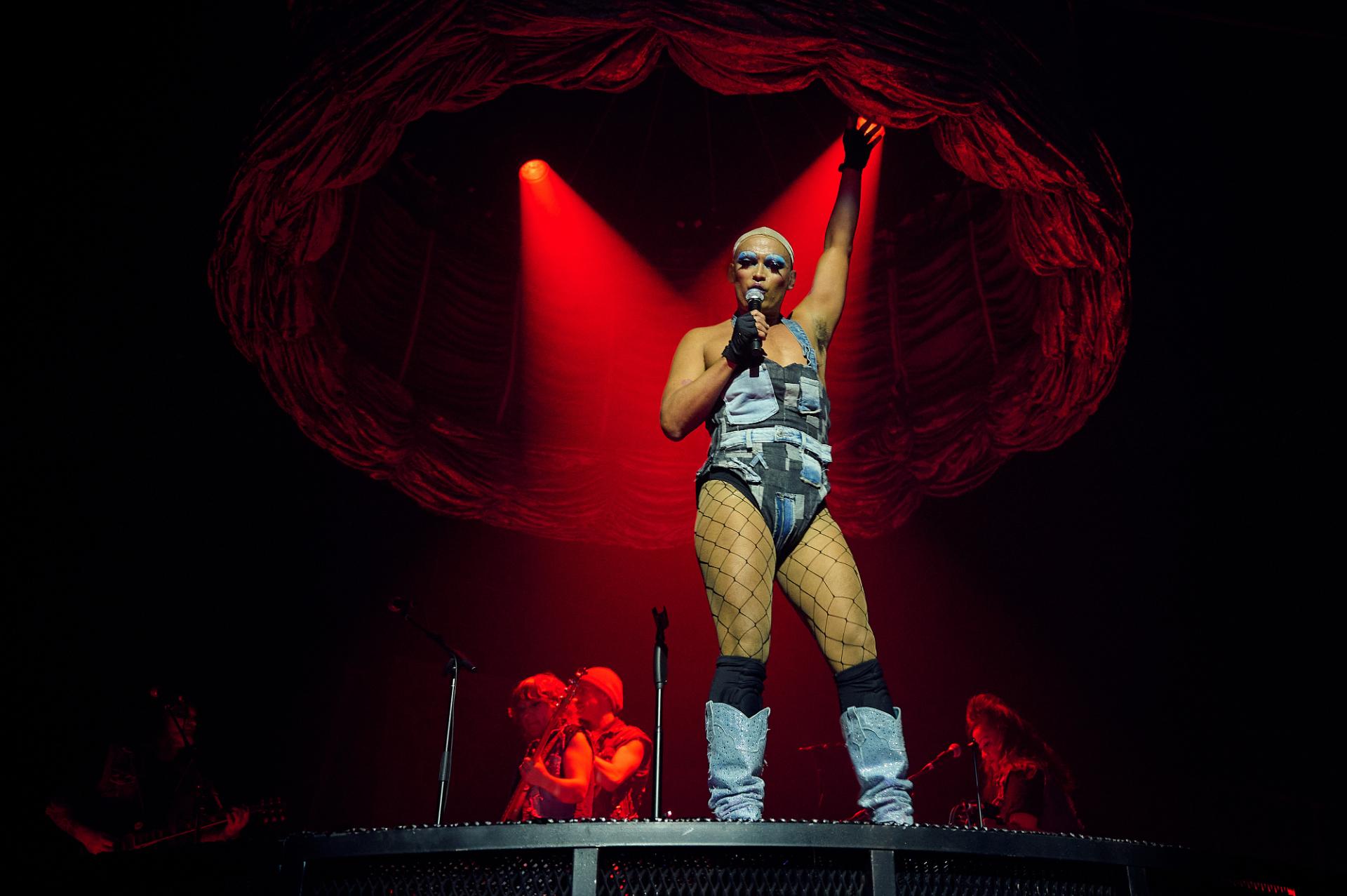

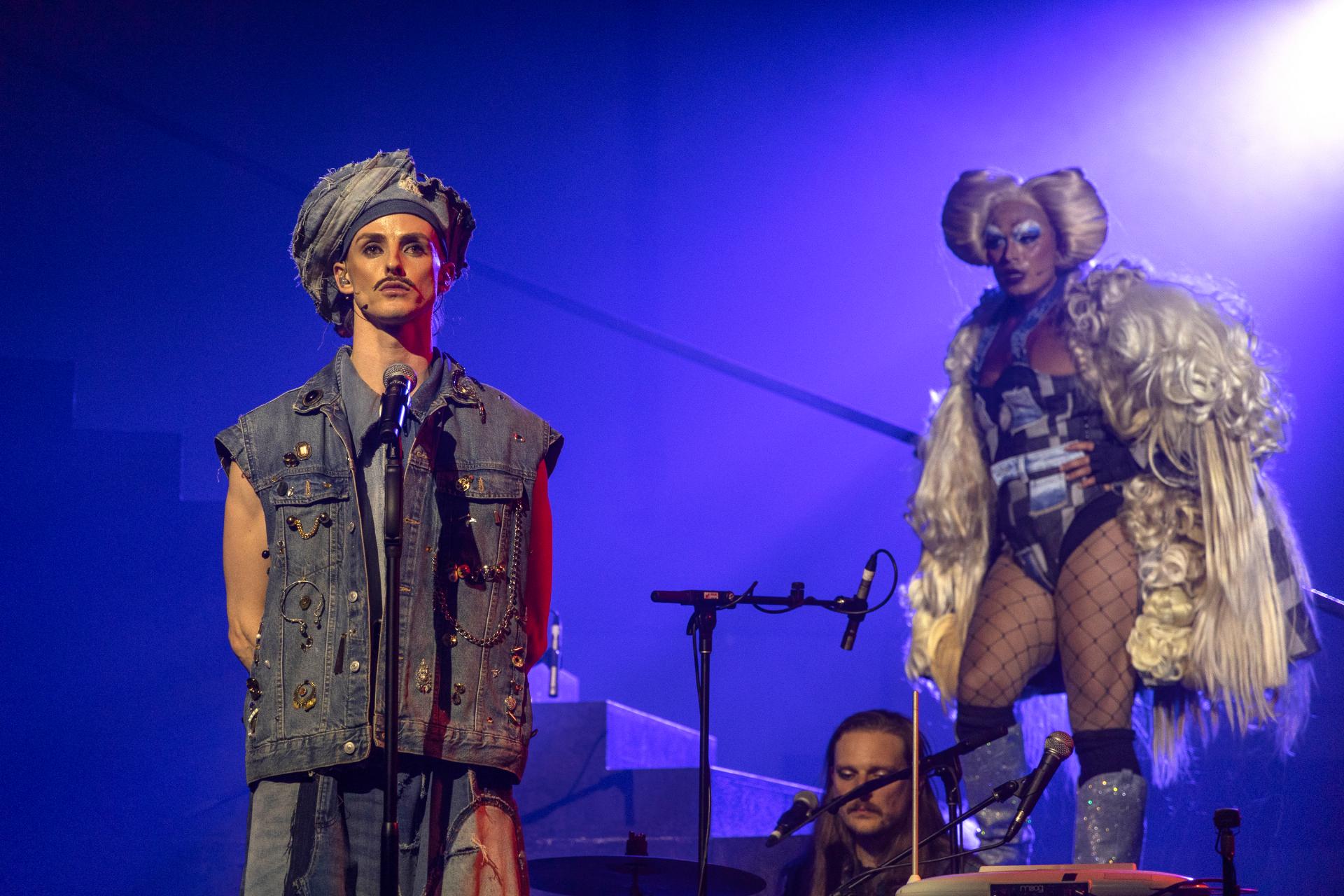

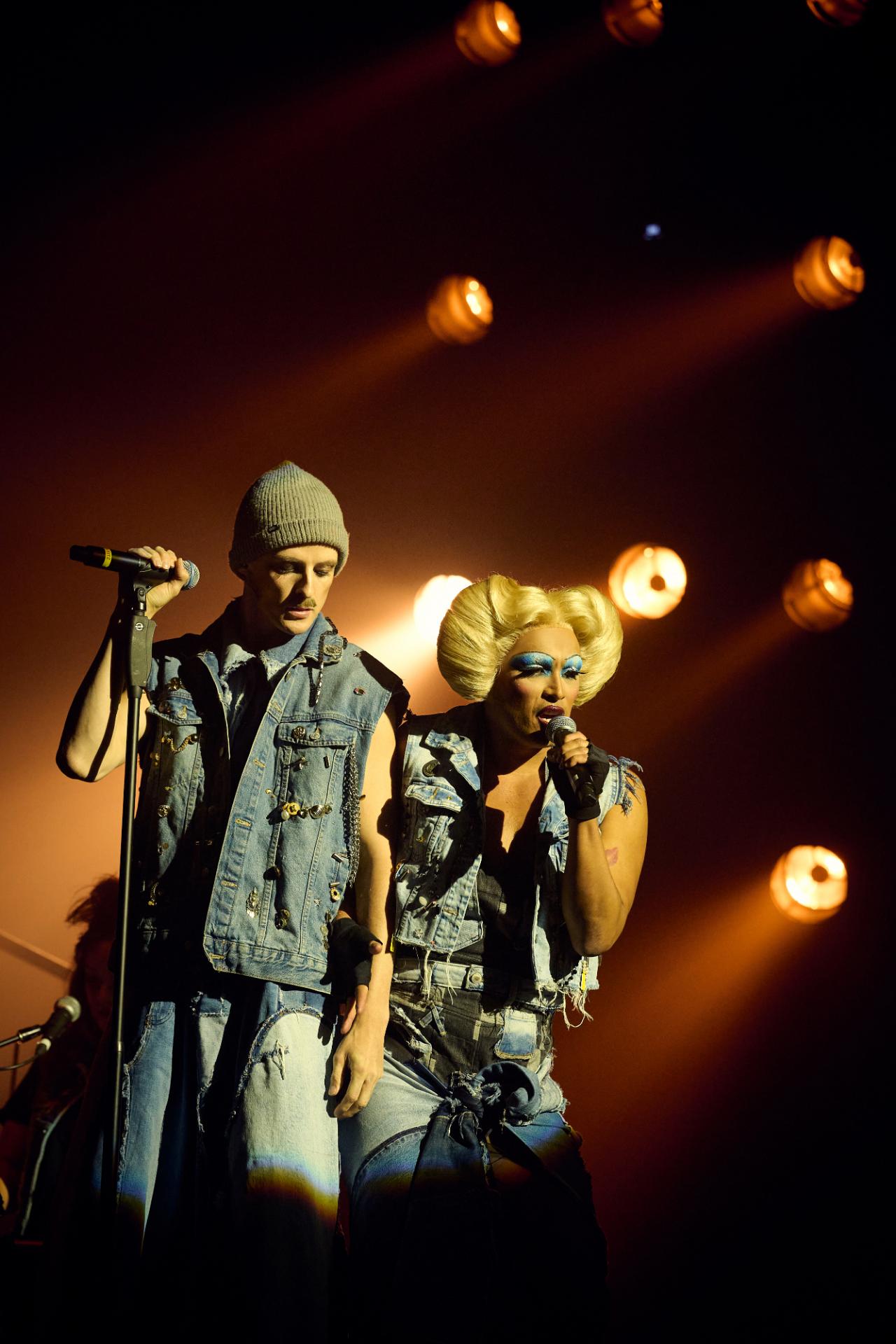

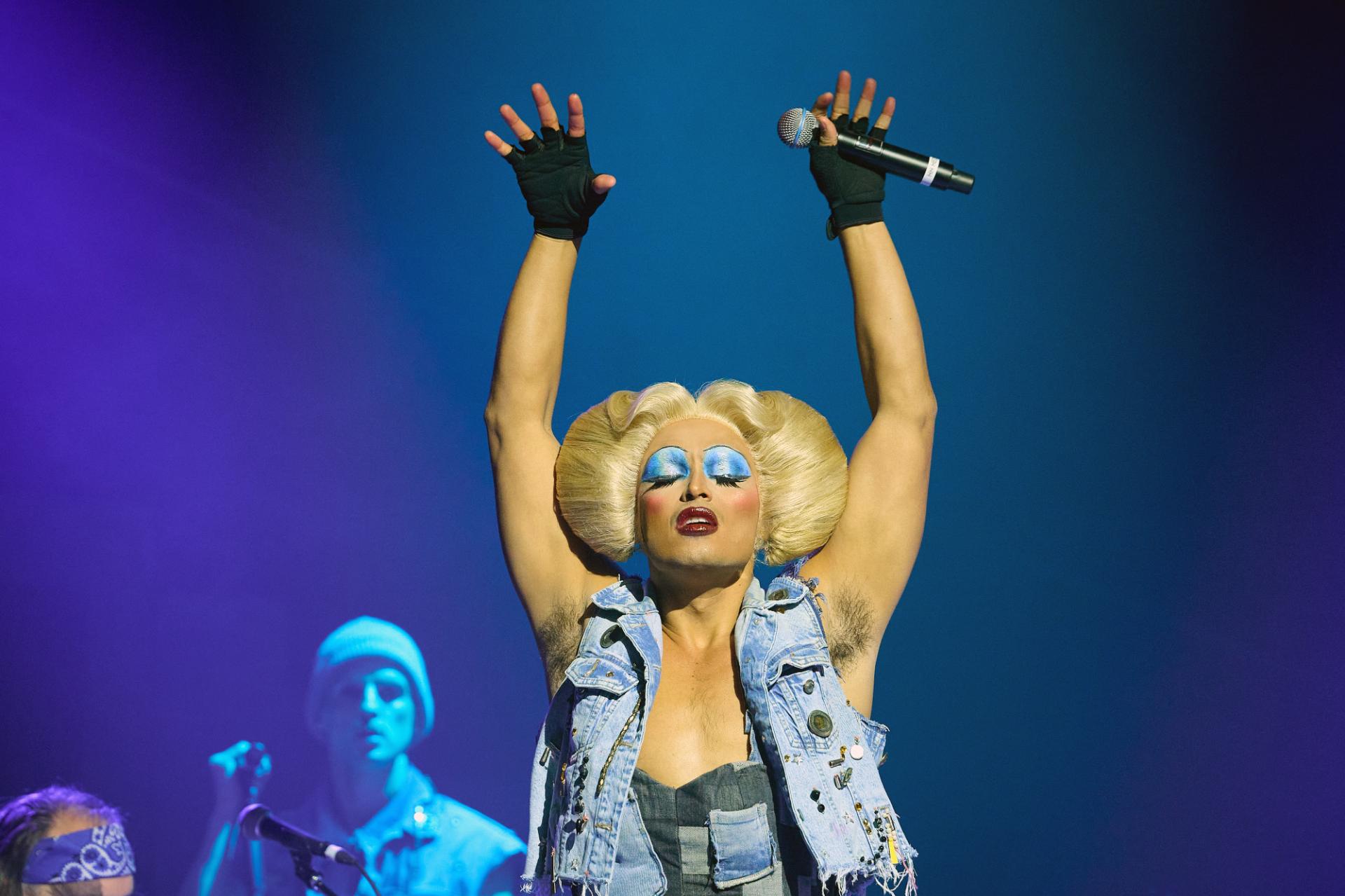

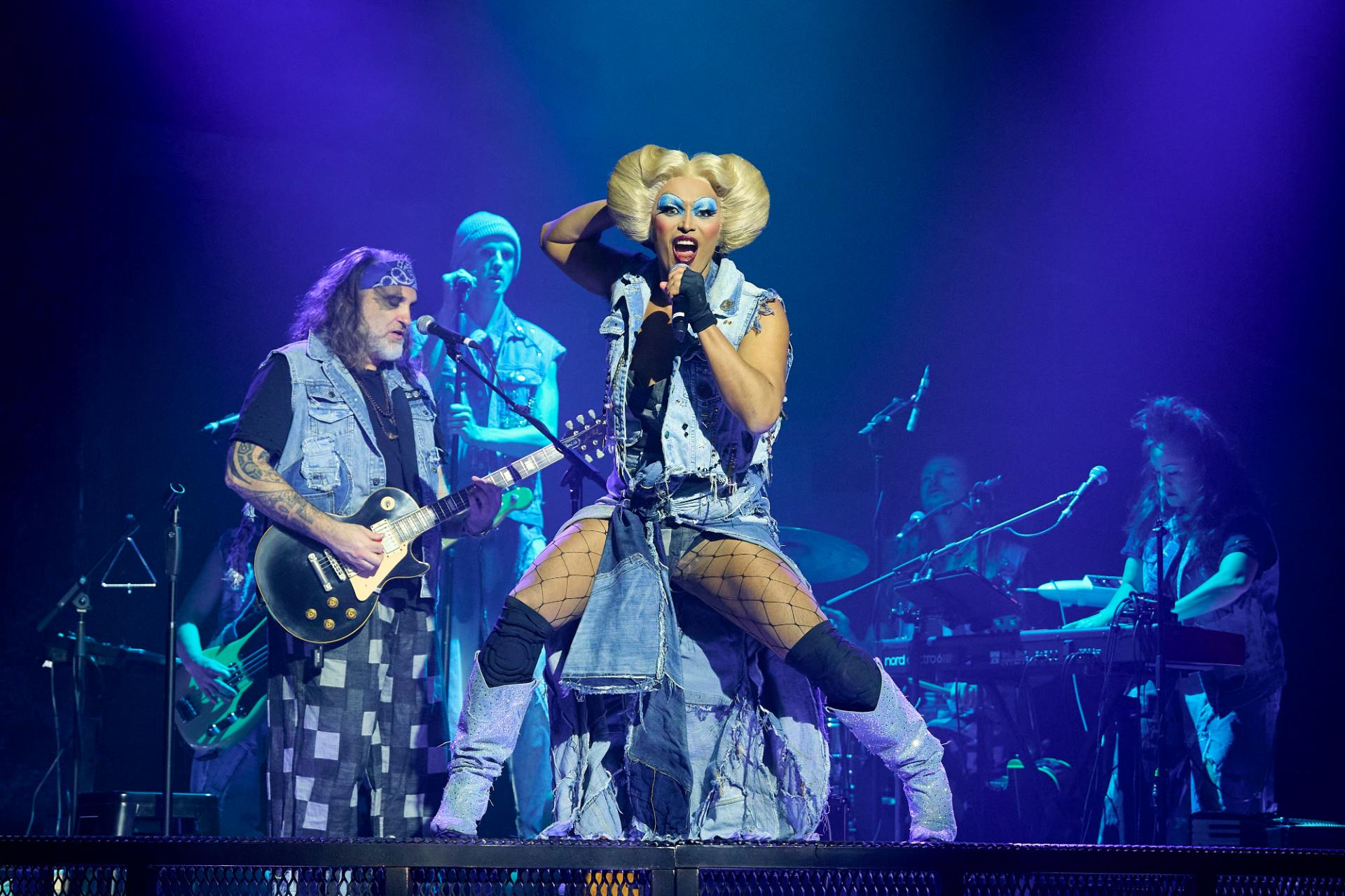

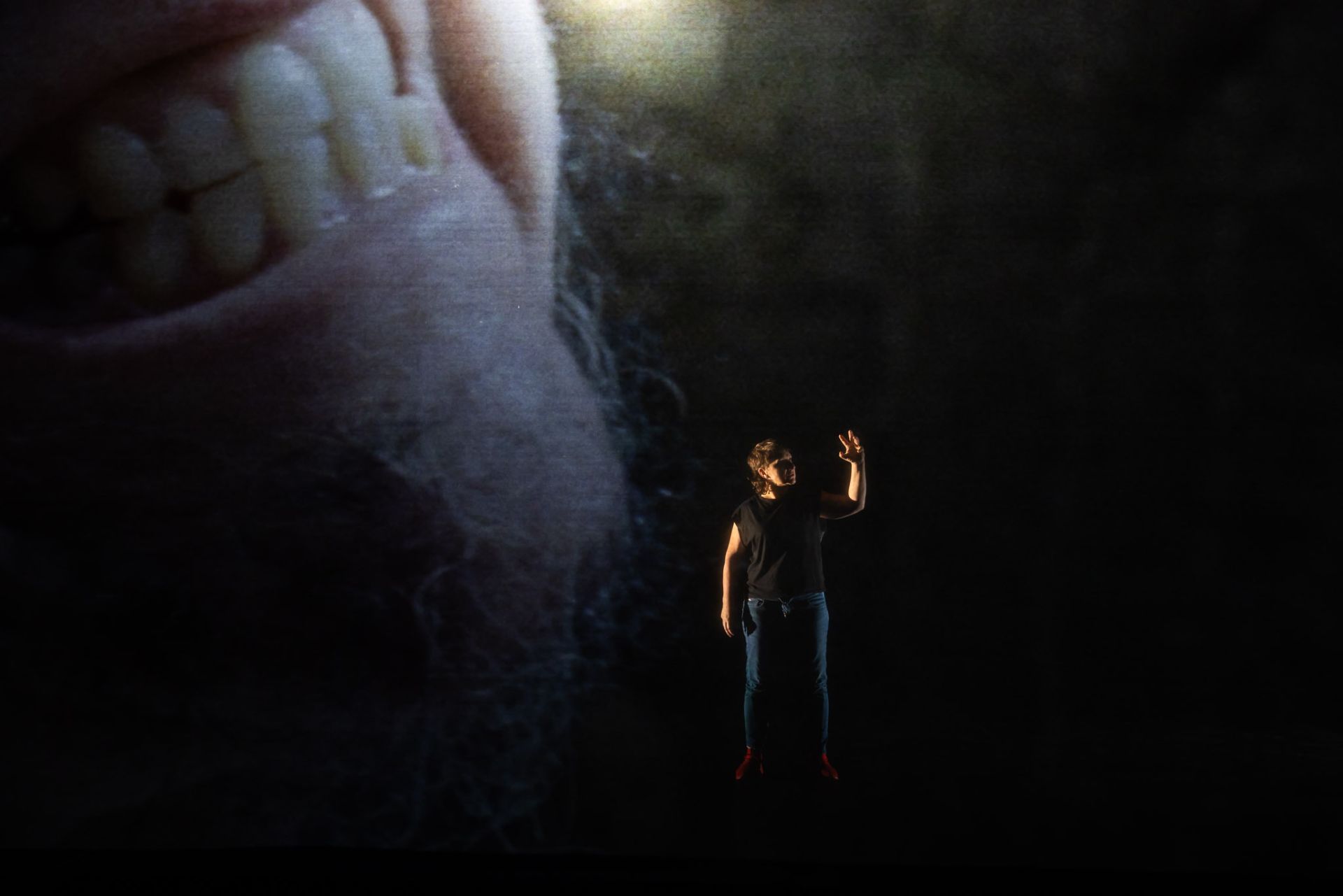

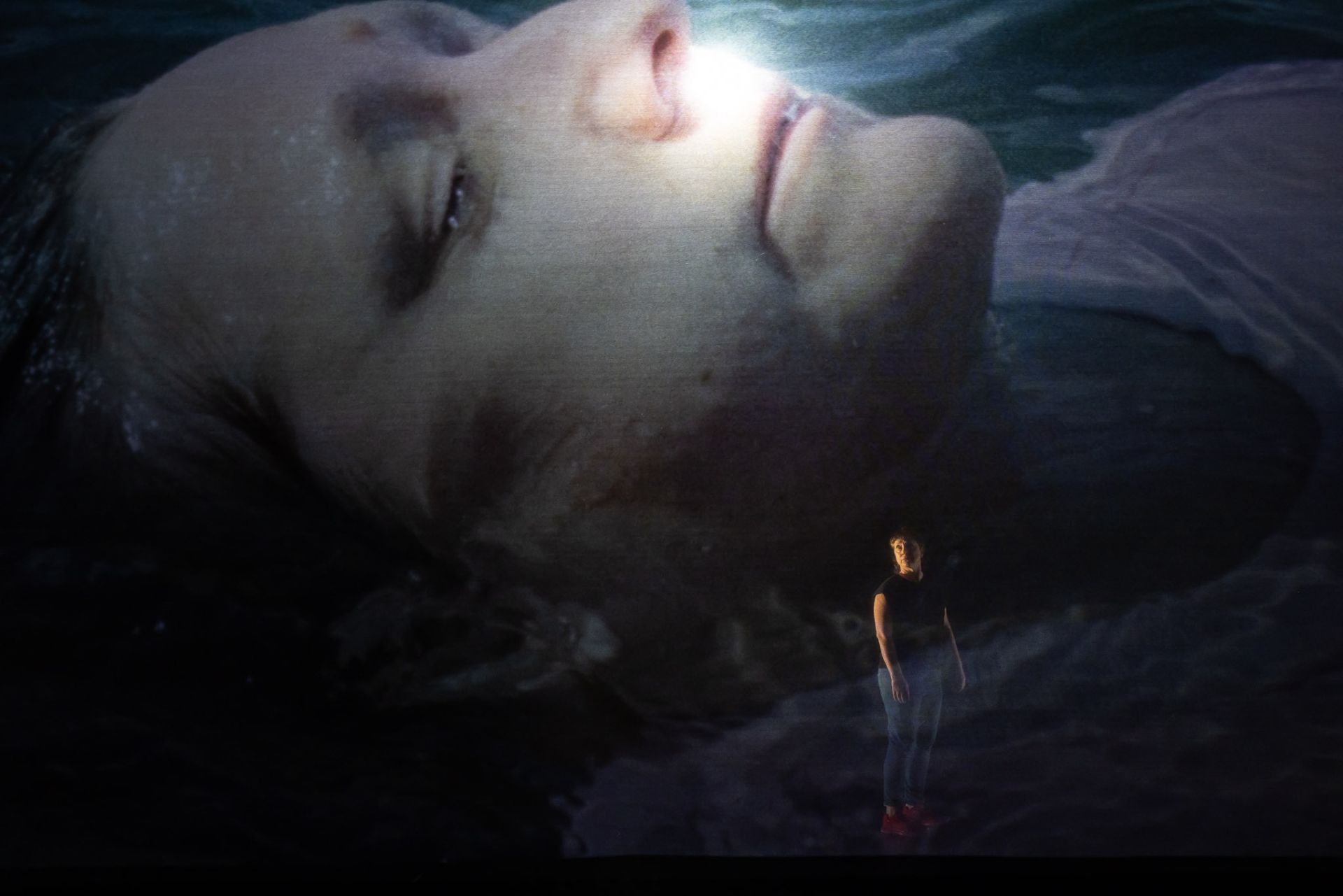

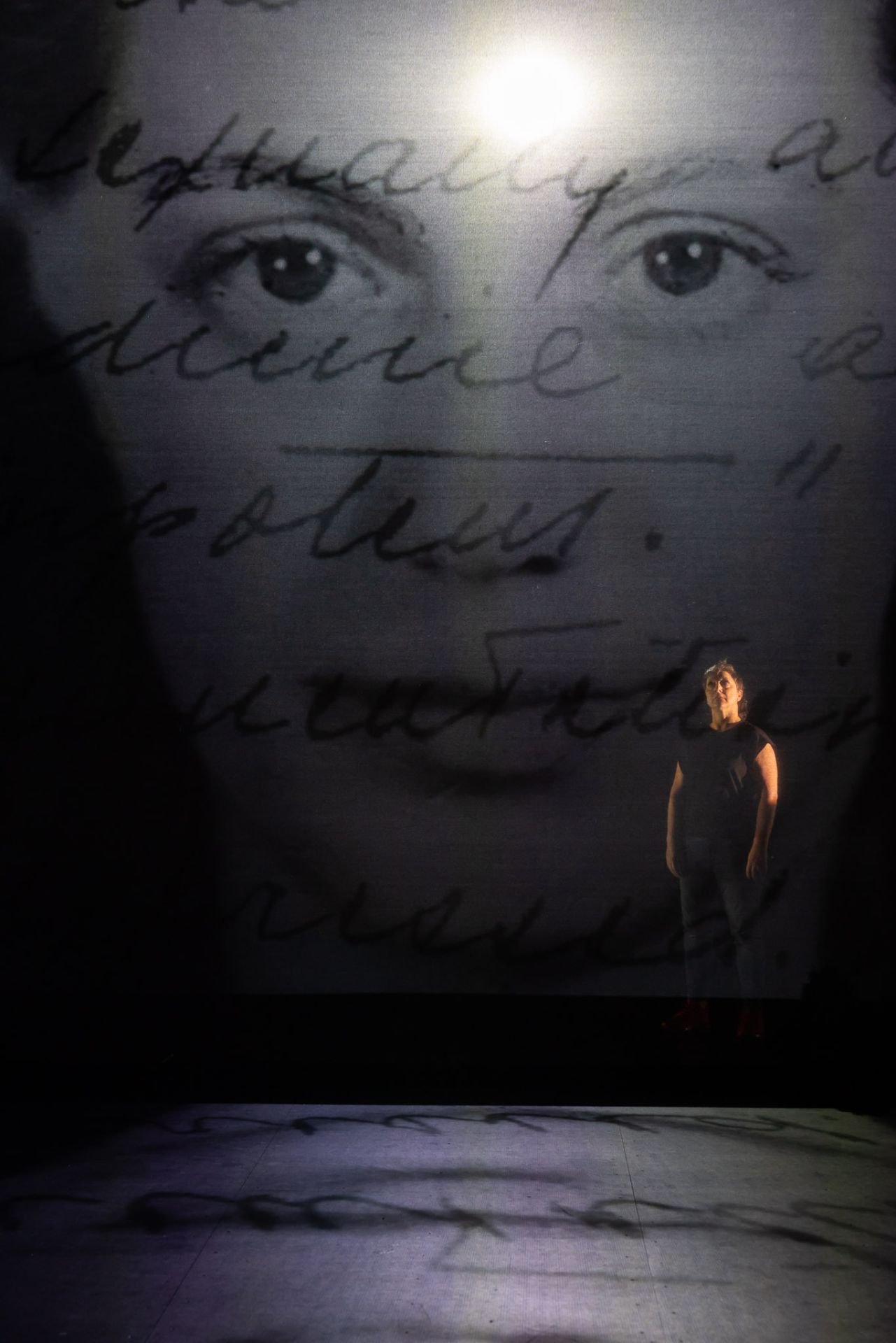

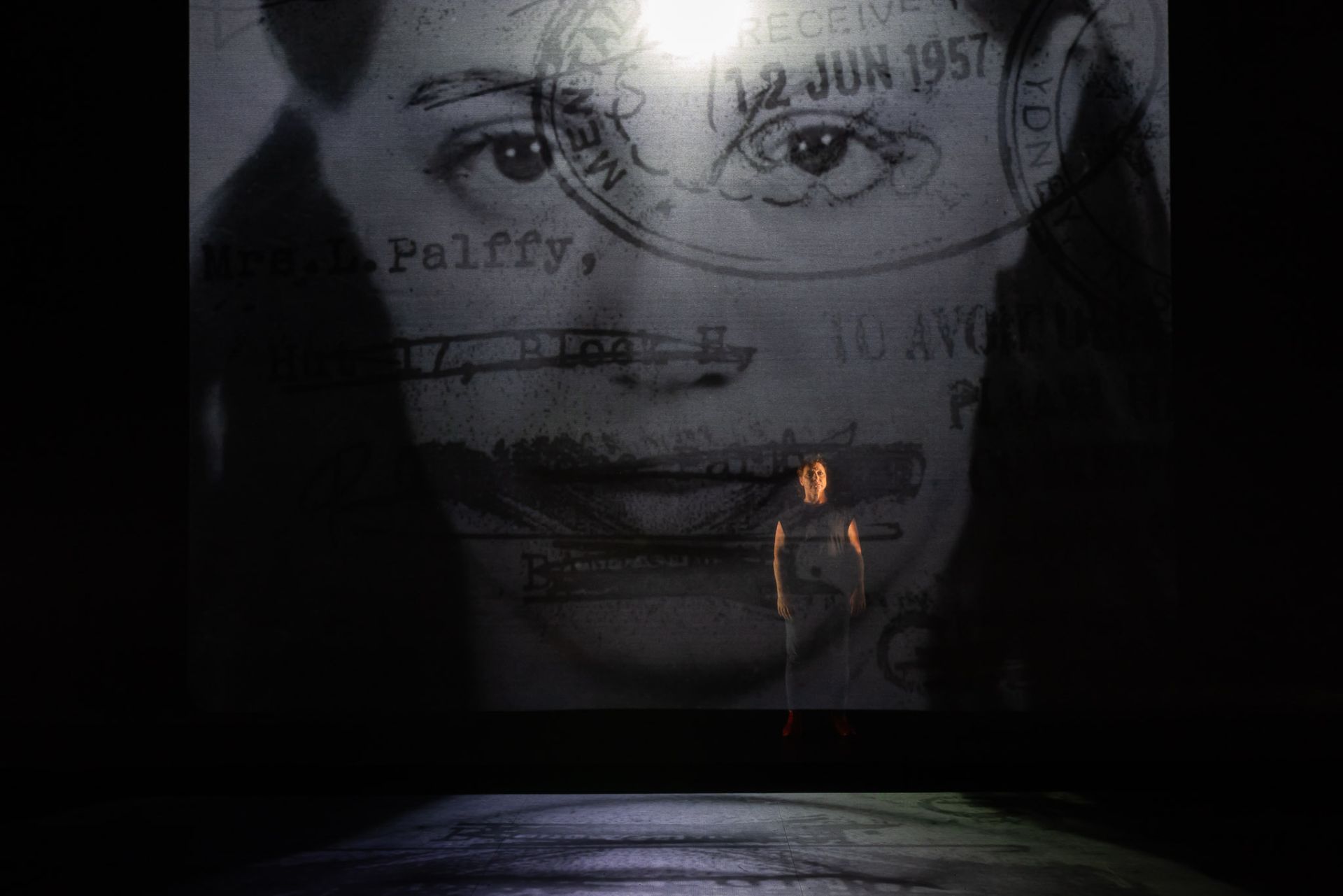

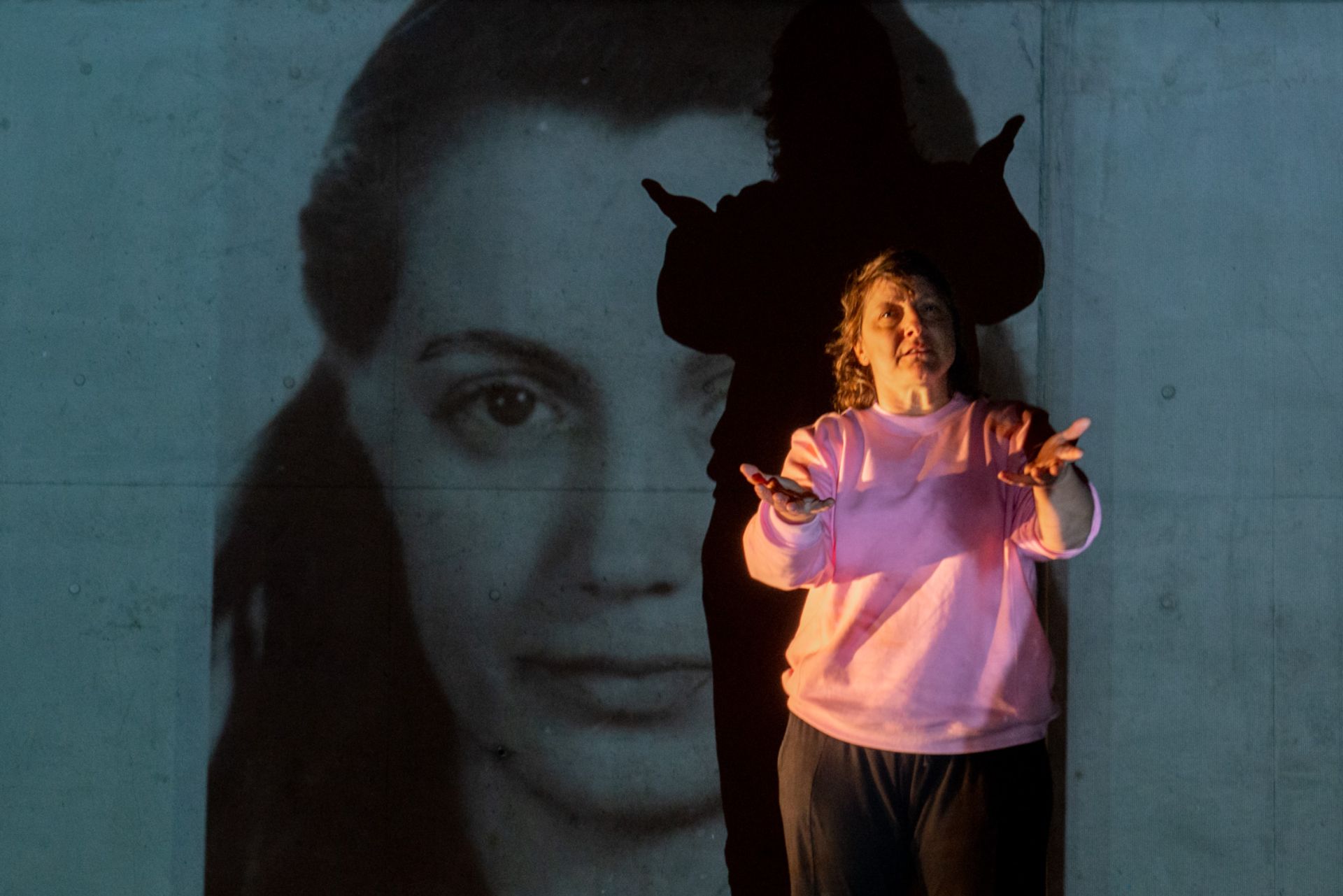

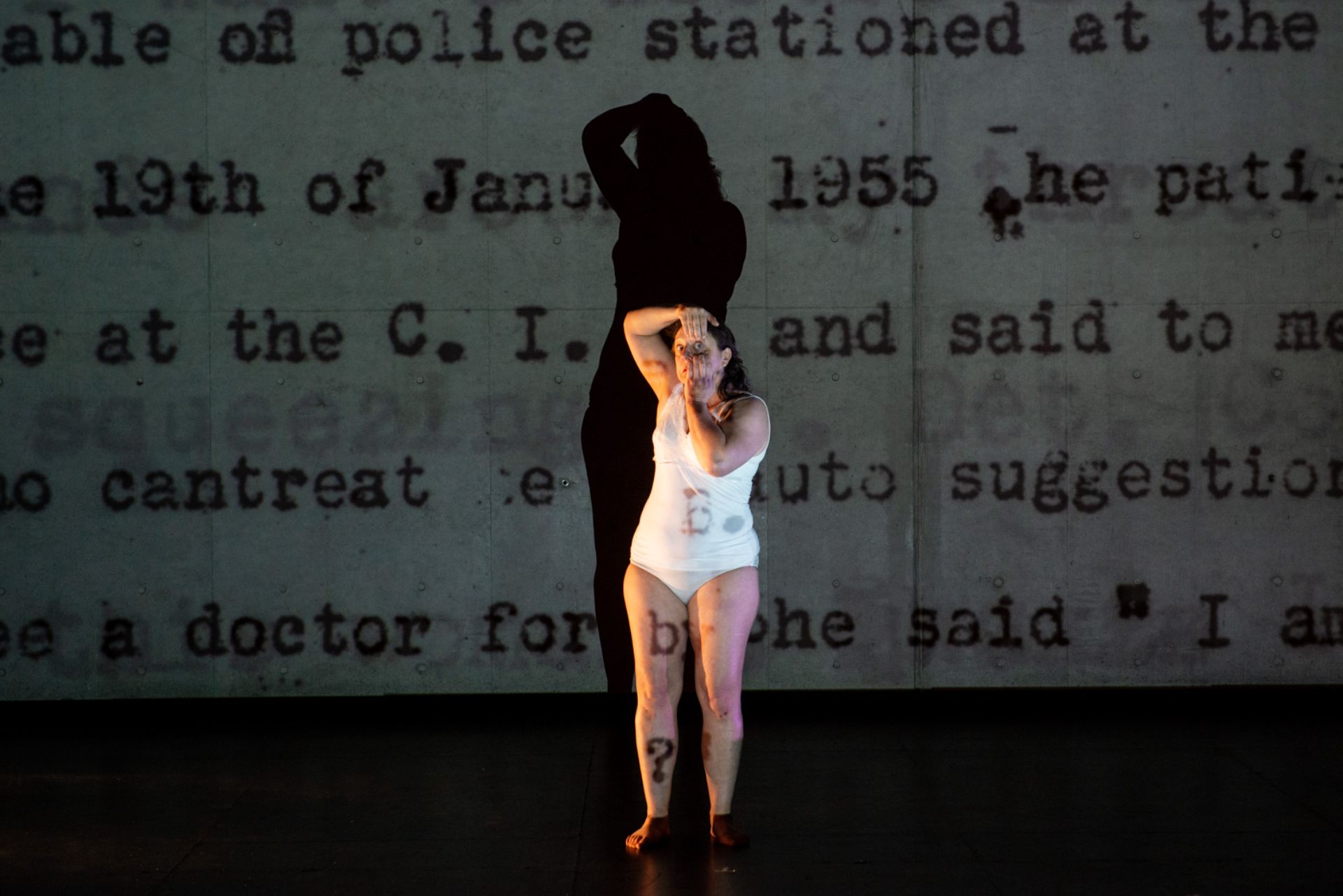

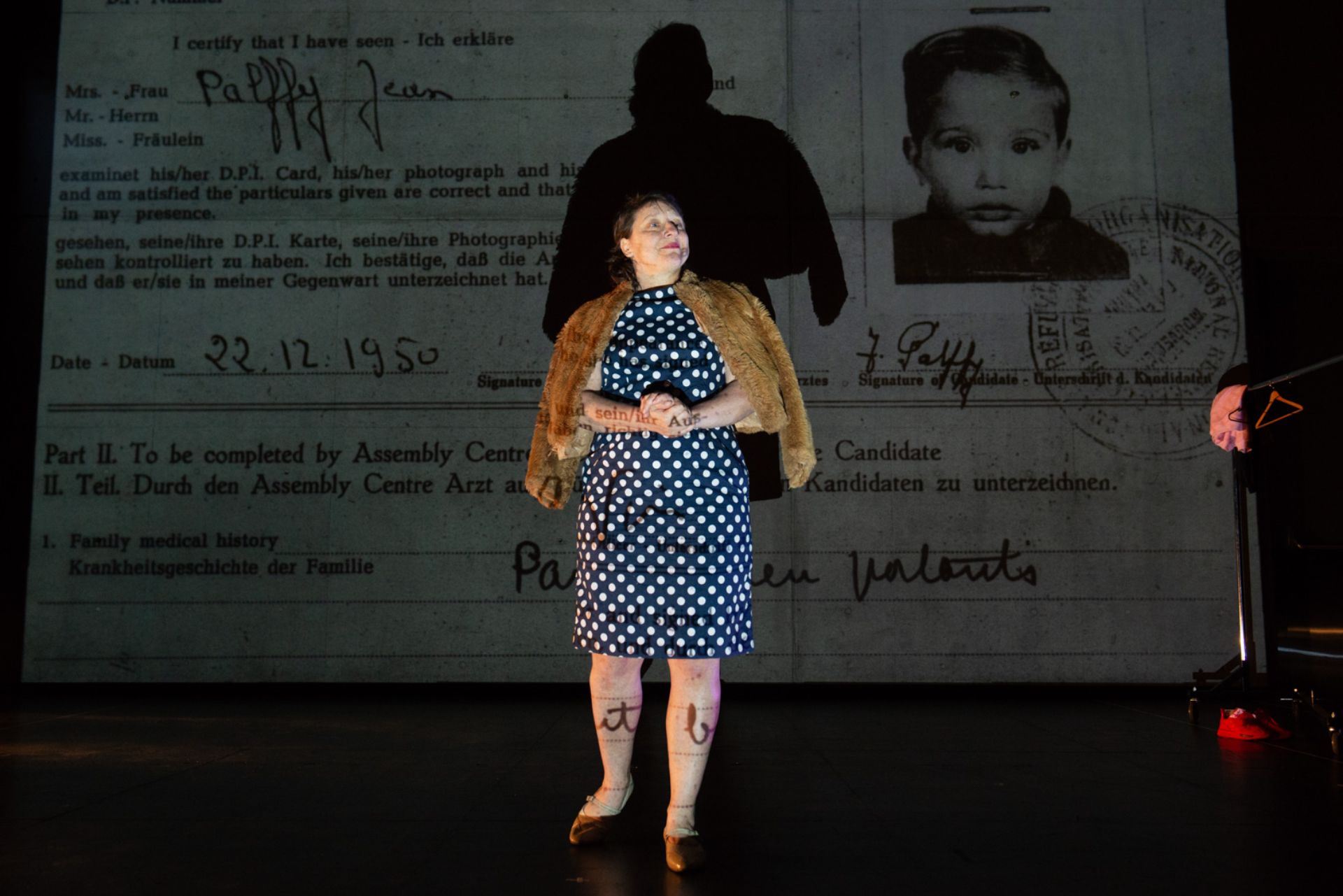

Image by Alec Council

Theatre review

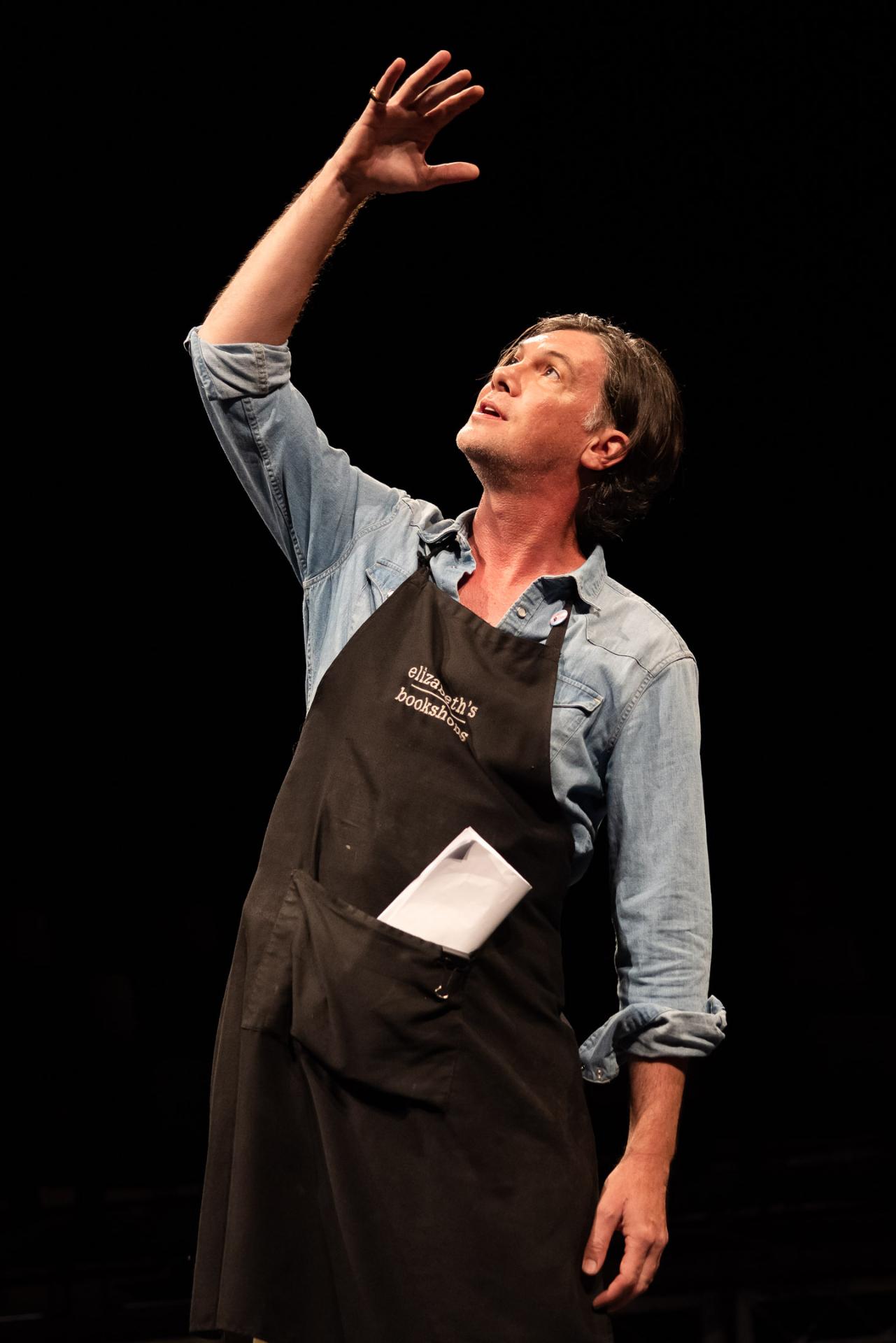

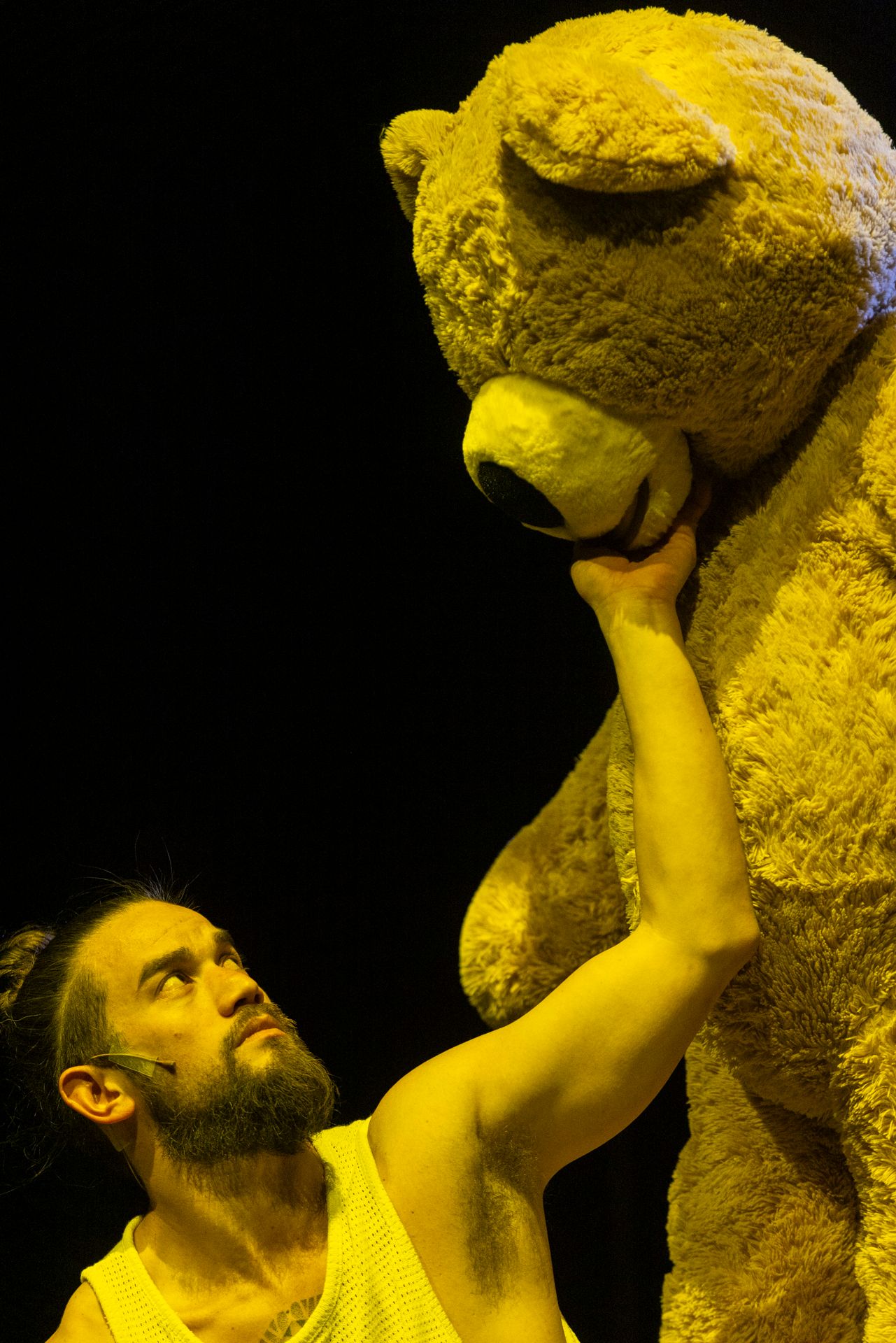

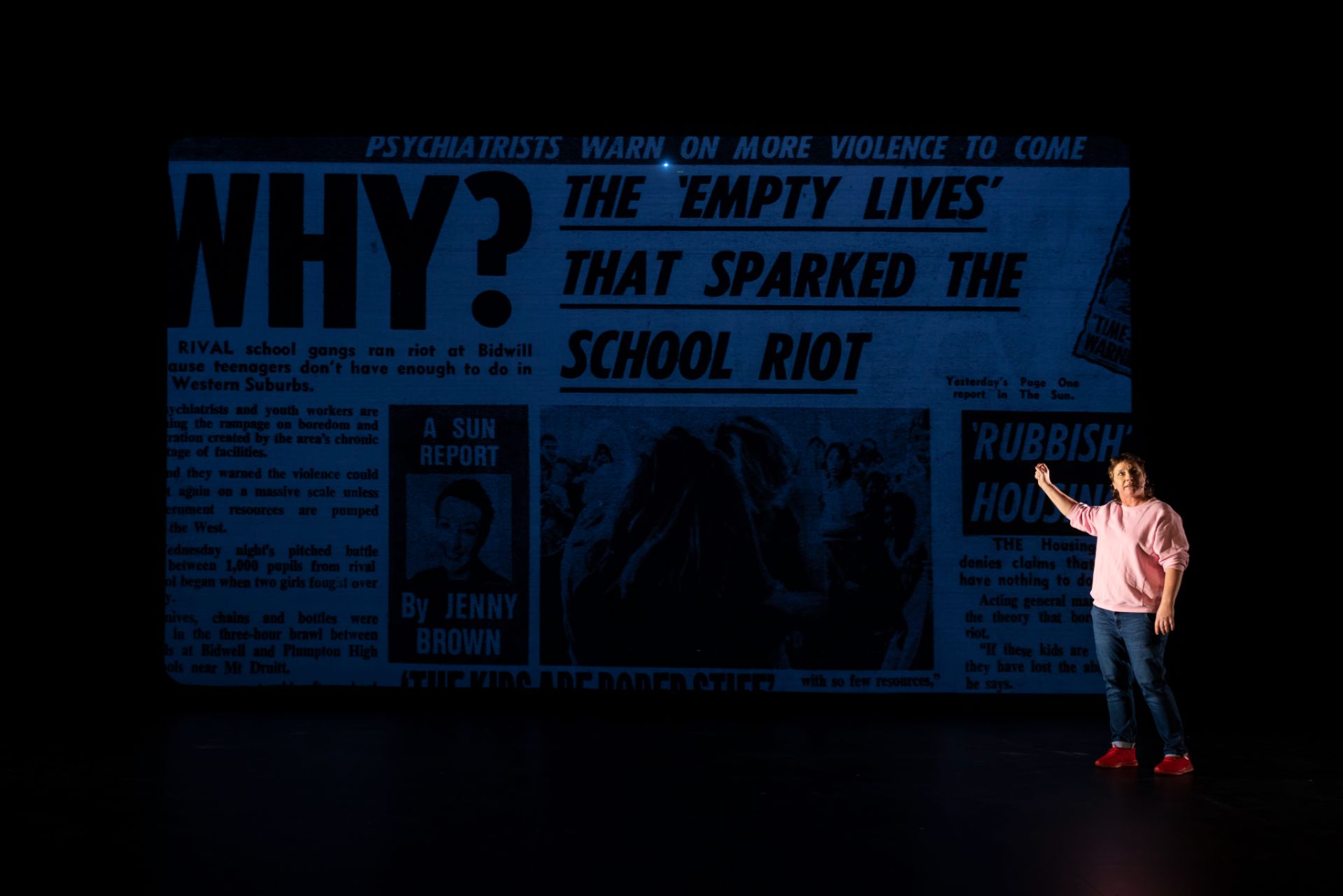

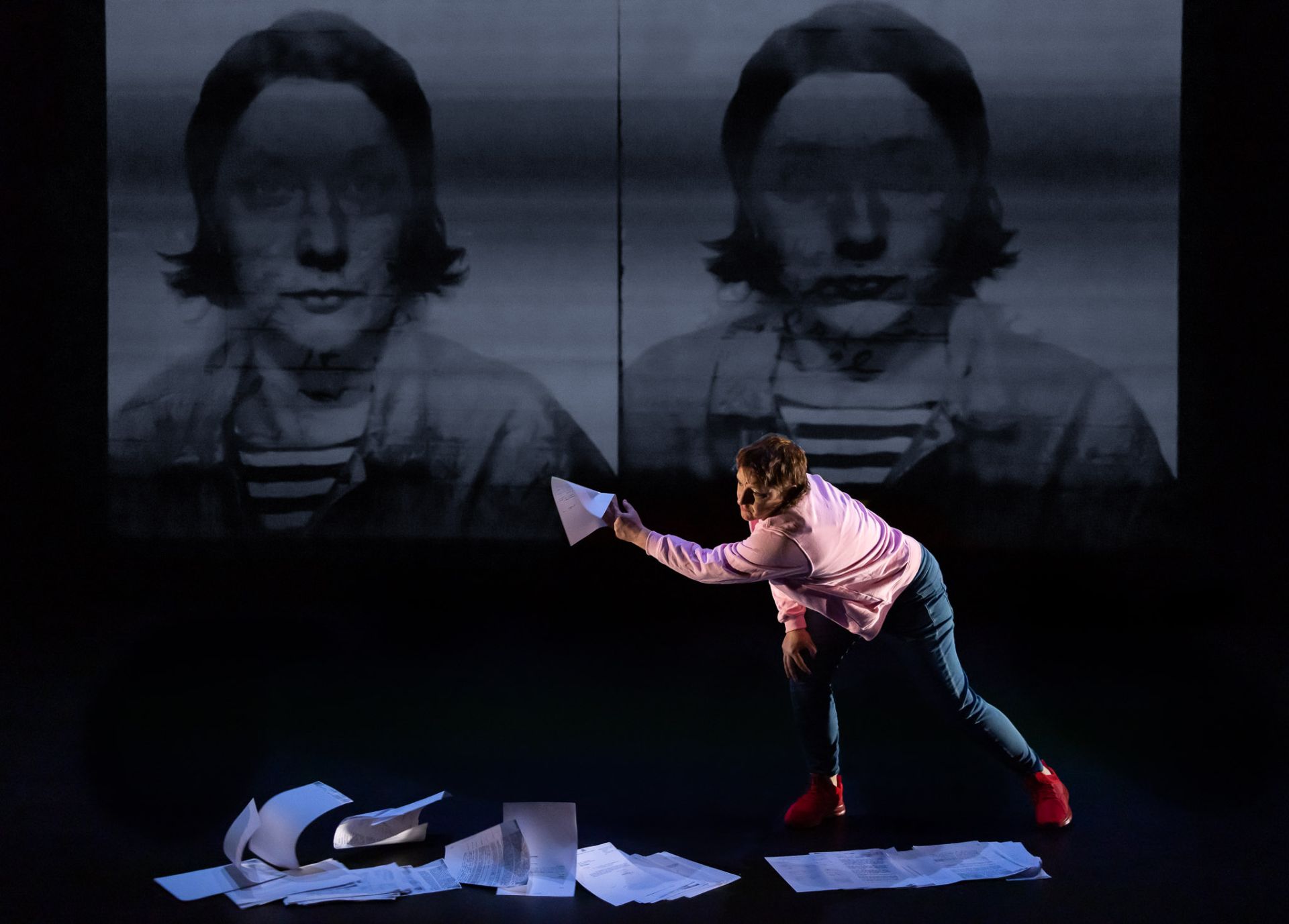

The show opens with the artist preparing to head out for a date. Poised before a mirror and confronted by his own reflection, it becomes clear that what is being rehearsed is less a social ritual than a state of psychological readiness—an attempt to negotiate self-doubt as much as appearance. Daley Rangi’s Takatāpui is a one-person work that interrogates otherness and marginalisation. Rangi occupies multiple positions of difference: Māori within a predominantly white world, and visibly queer within a milieu structured by heteronormativity. Almost inevitably, the work unfolds as a meditation on isolation and loneliness, tracing the quiet distances that emerge when identity is continually rendered peripheral.

Takatāpui is threaded with humour, though its gravity is never in doubt. Rangi’s magnetism holds the audience in effortless thrall across the hour-long duration, his lucid embodiment of complex emotional states lending a visceral clarity to the poetic language he deploys with such quiet authority. What emerges is a portrait of profound vulnerability tempered by considerable strength: in his reflections on being brown and trans, Rangi articulates a narrative of injustice that resonates deeply, not as abstraction but as lived experience, felt and shared in the room.

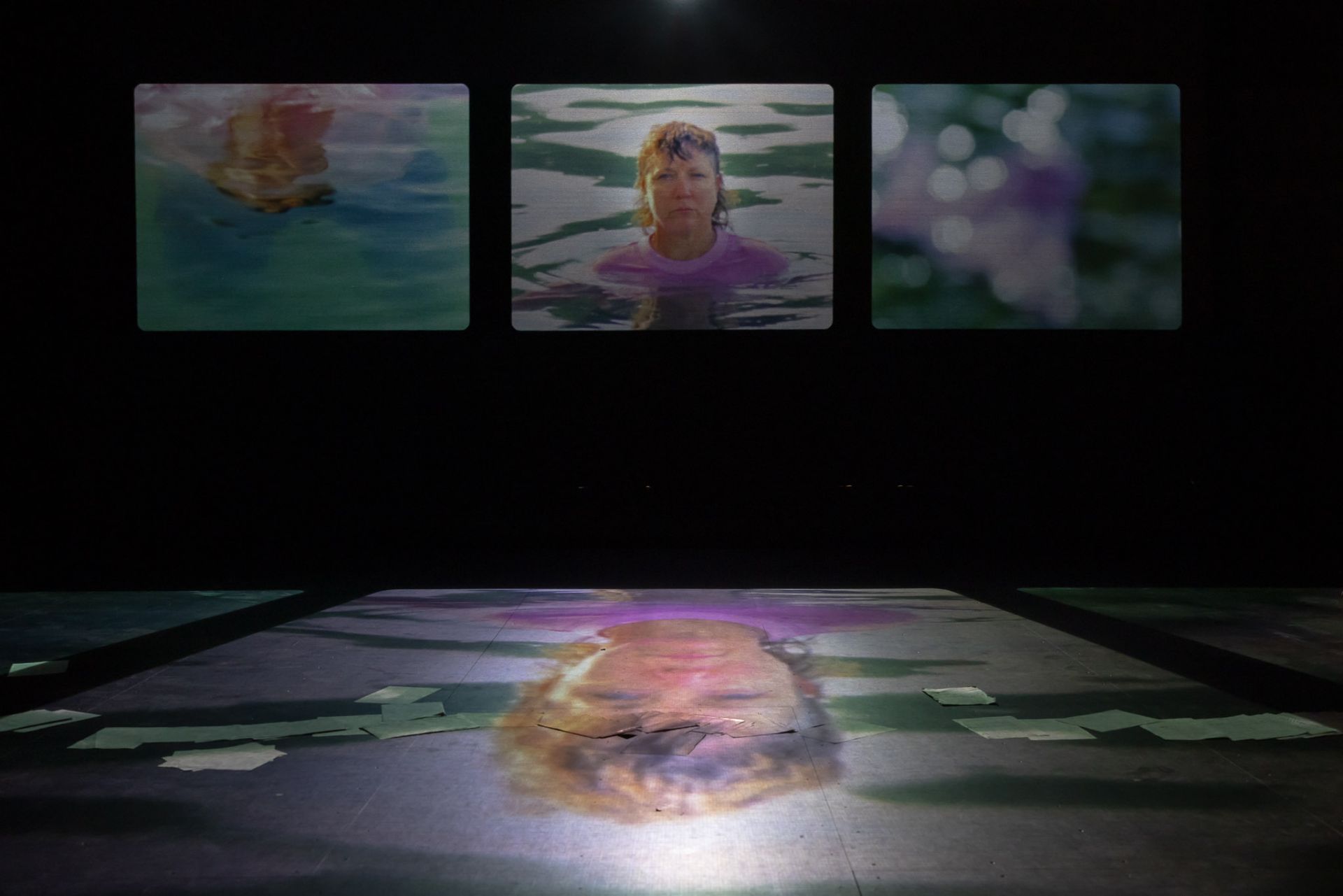

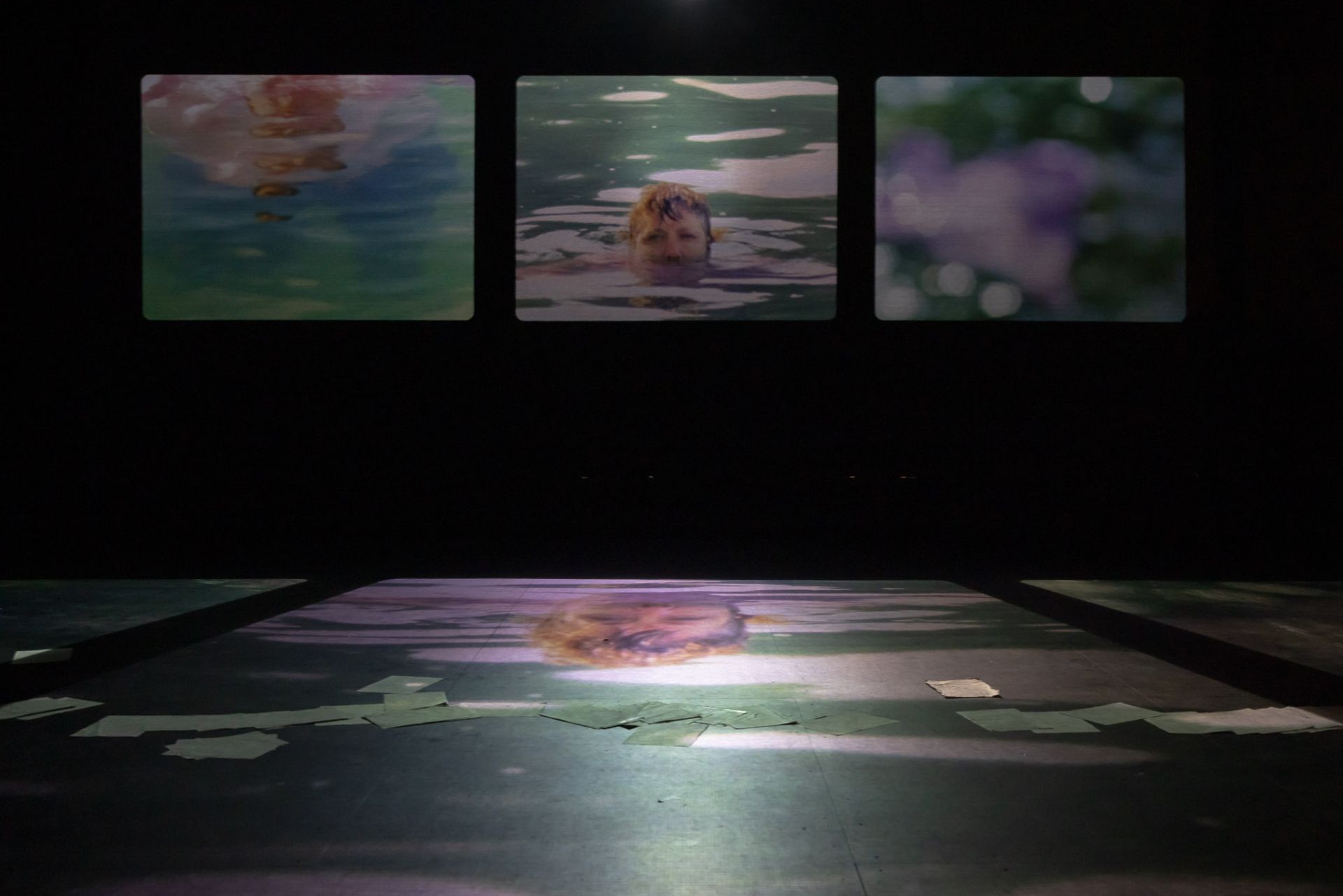

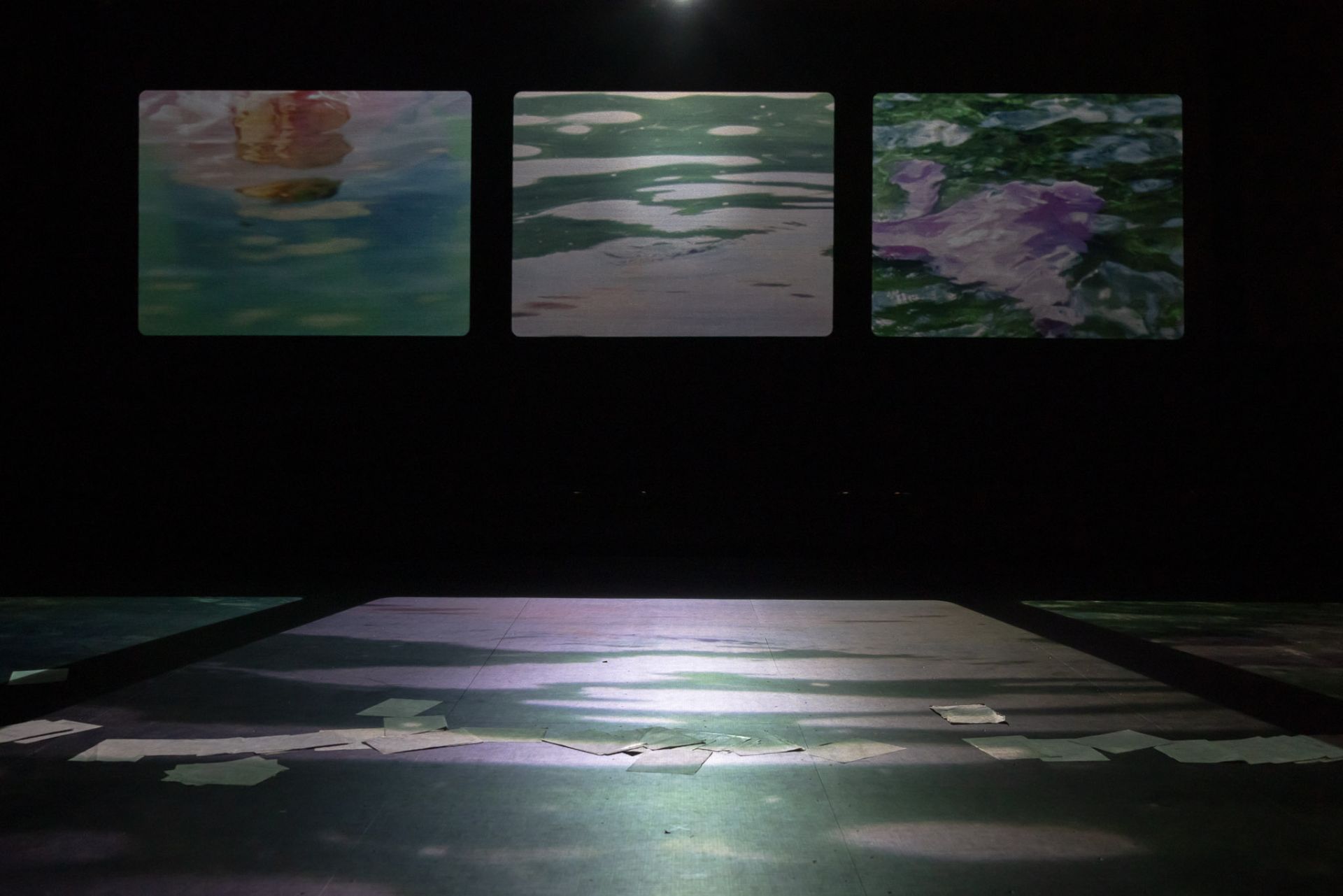

It is striking that, despite being staged within the starkest of settings—an empty stage anchored only by a microphone stand outfitted with small electronic contraptions—the production’s lighting and sound design are intricately conceived and exuberantly realised. These elements do far more than support the action: they actively extend and enrich the storytelling. The resulting sensorial depth comes as a welcome surprise, amplifying the work’s theatricality and lending a layered, immersive quality to what might otherwise read as austere minimalism.

Takatāpui is written from a place of profound personal intimacy, offering perspectives and experiences that are singular and unrepeatable. That human beings possess a means by which such interiority can be shared at all is something to be cherished and fiercely defended. Art may be intrinsic to our species, yet it remains fragile—perpetually vulnerable to being sidelined, muted, or censored. In the present moment, artists have become increasingly rare, and alarmingly, this scarcity is met with a troubling complacency: an acceptance that human endeavour should be reduced to the bare logic of economic survival. To relegate art to the realm of the rarefied, to treat it as a luxury rather than a necessity, is both a disgrace and a danger. In doing so, we risk forfeiting our capacity to apprehend meaning, complexity, and truth itself.

Venue: Carriageworks (Eveleigh NSW), Jan 20 – 24, 2021

Venue: Carriageworks (Eveleigh NSW), Jan 20 – 24, 2021