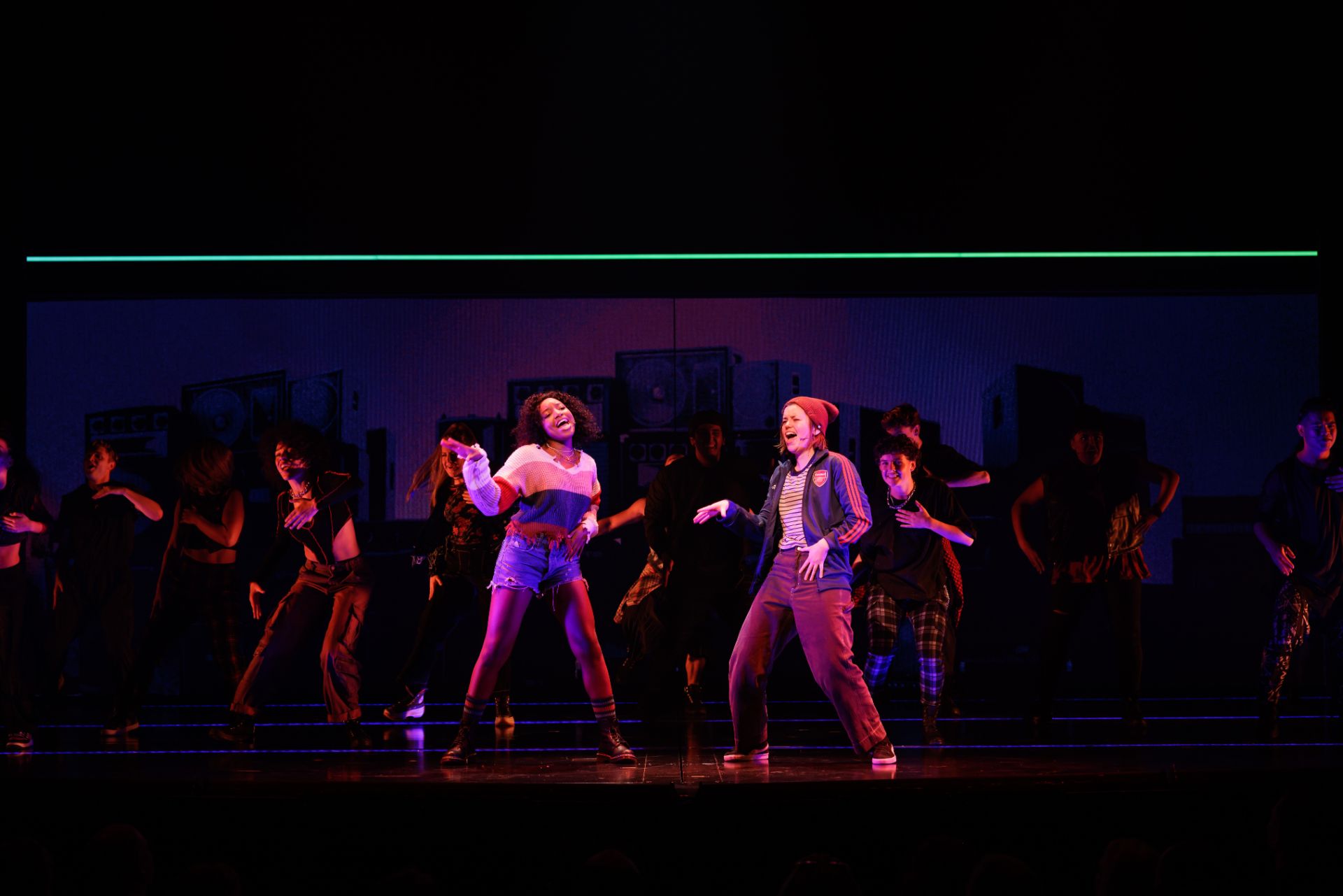

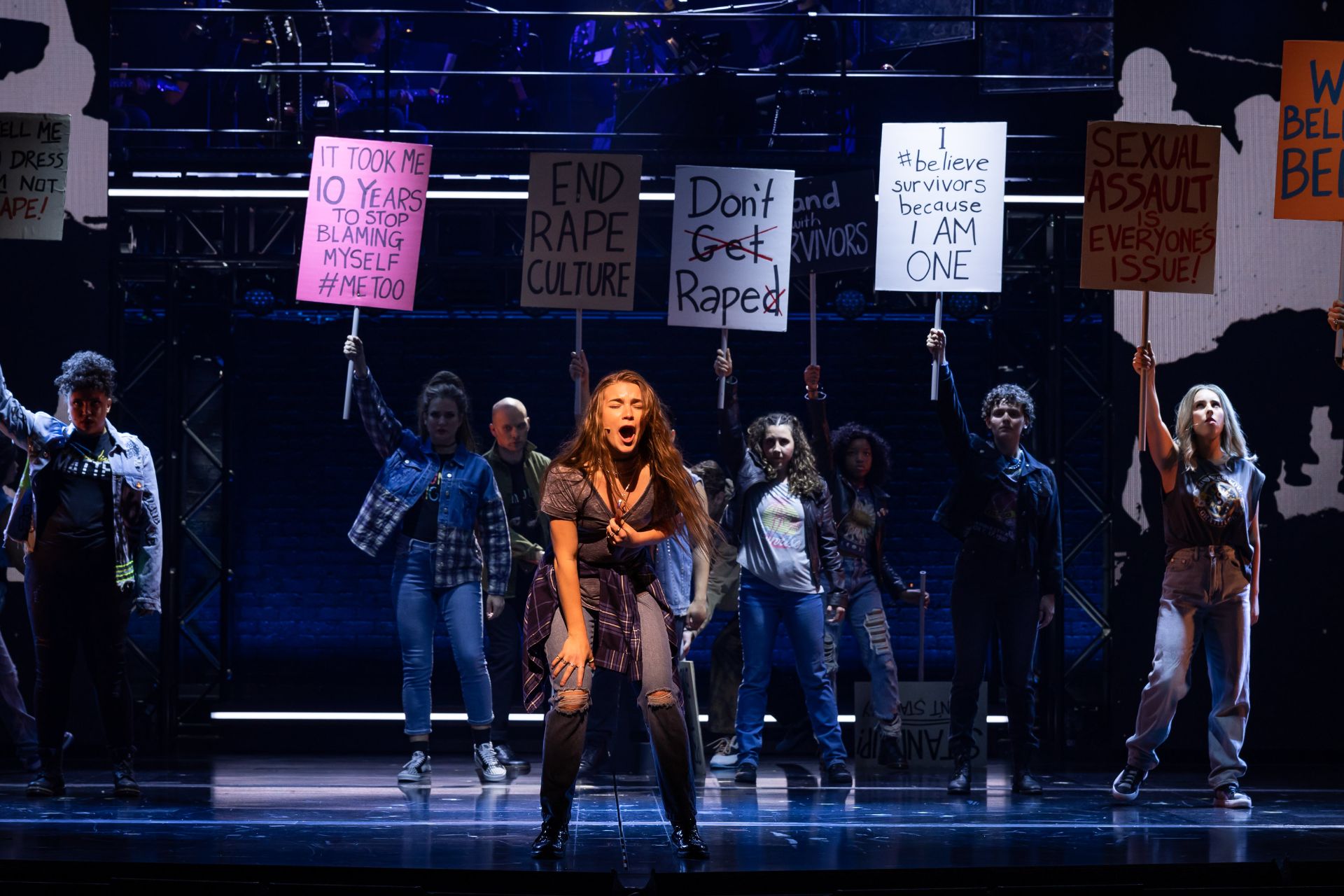

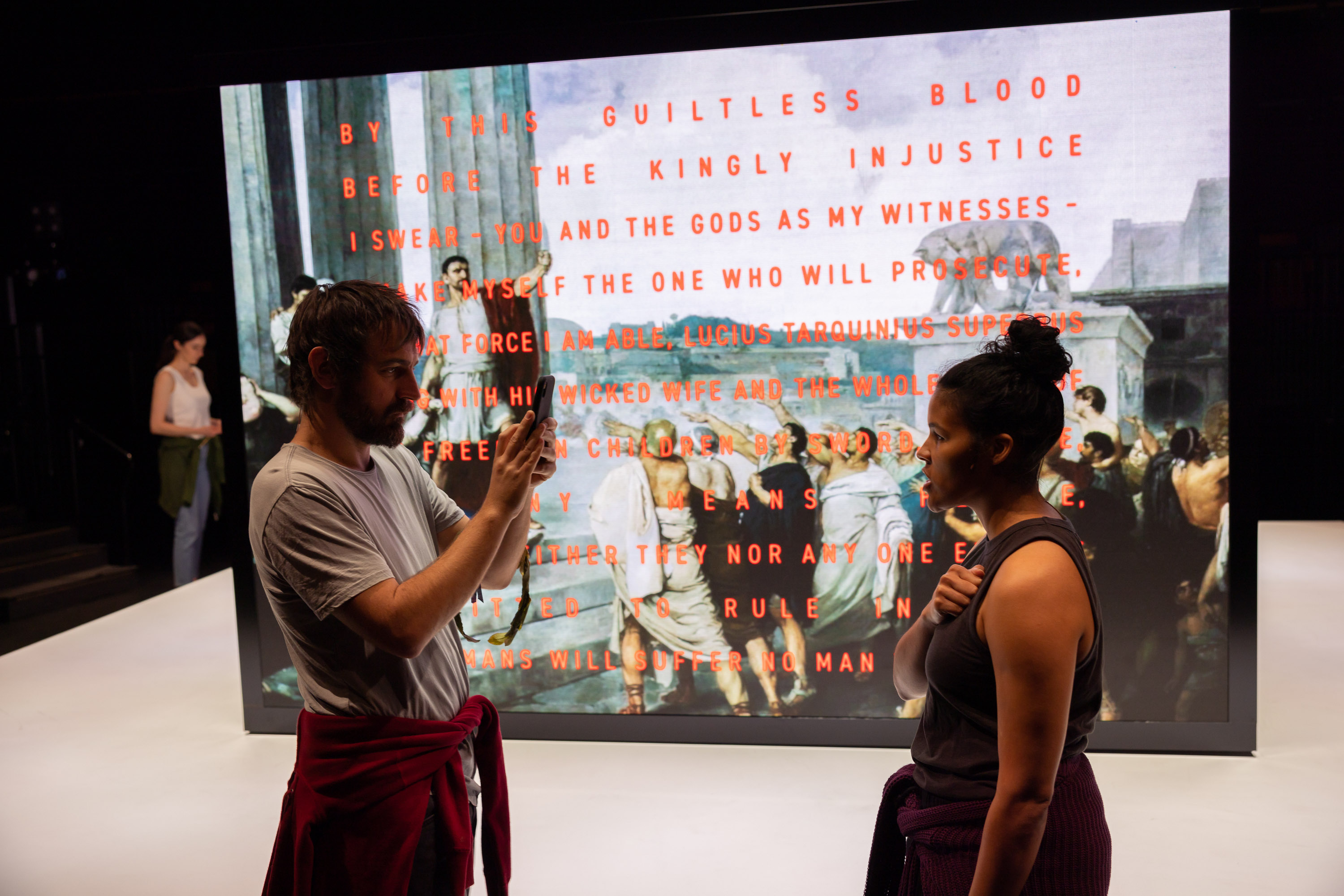

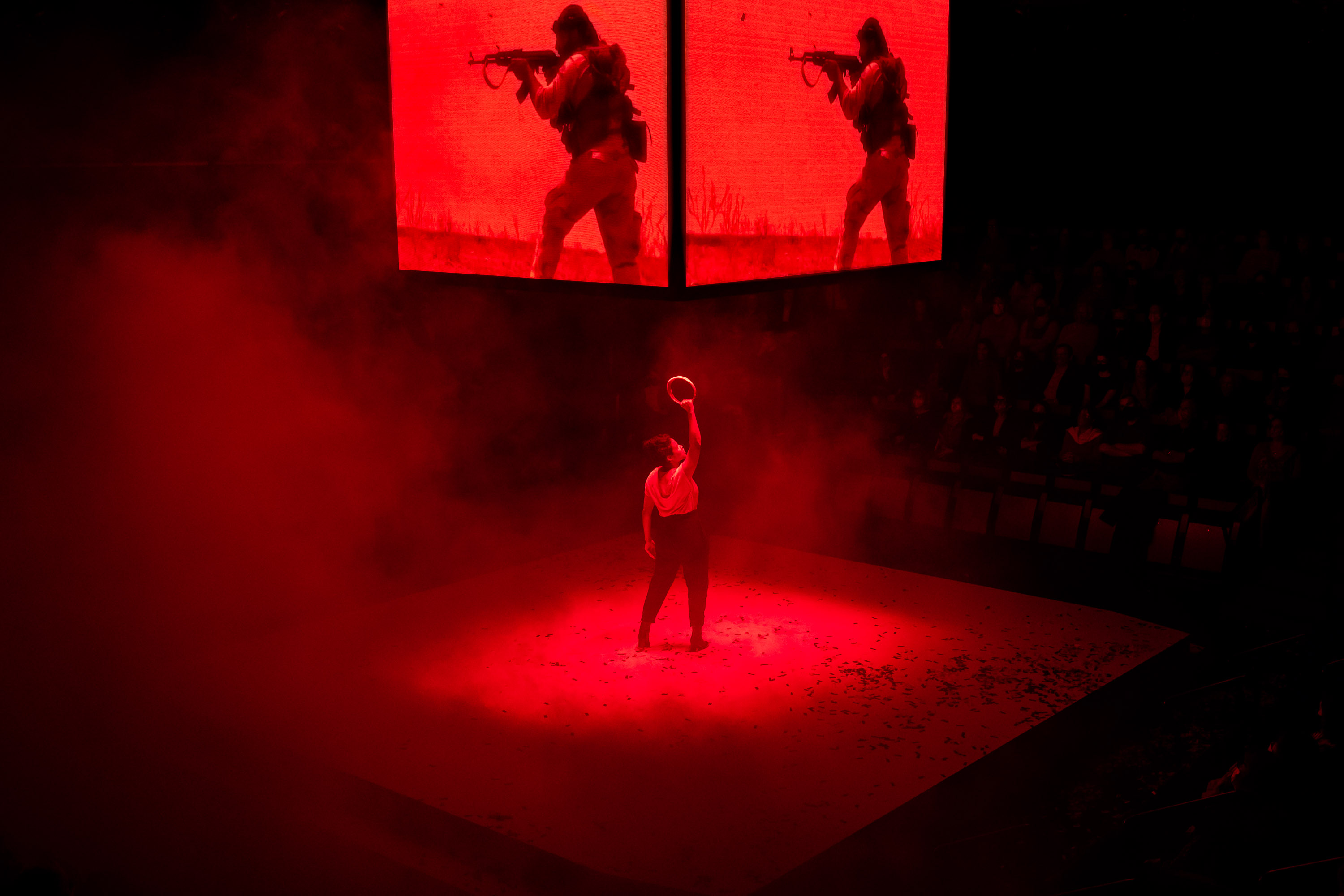

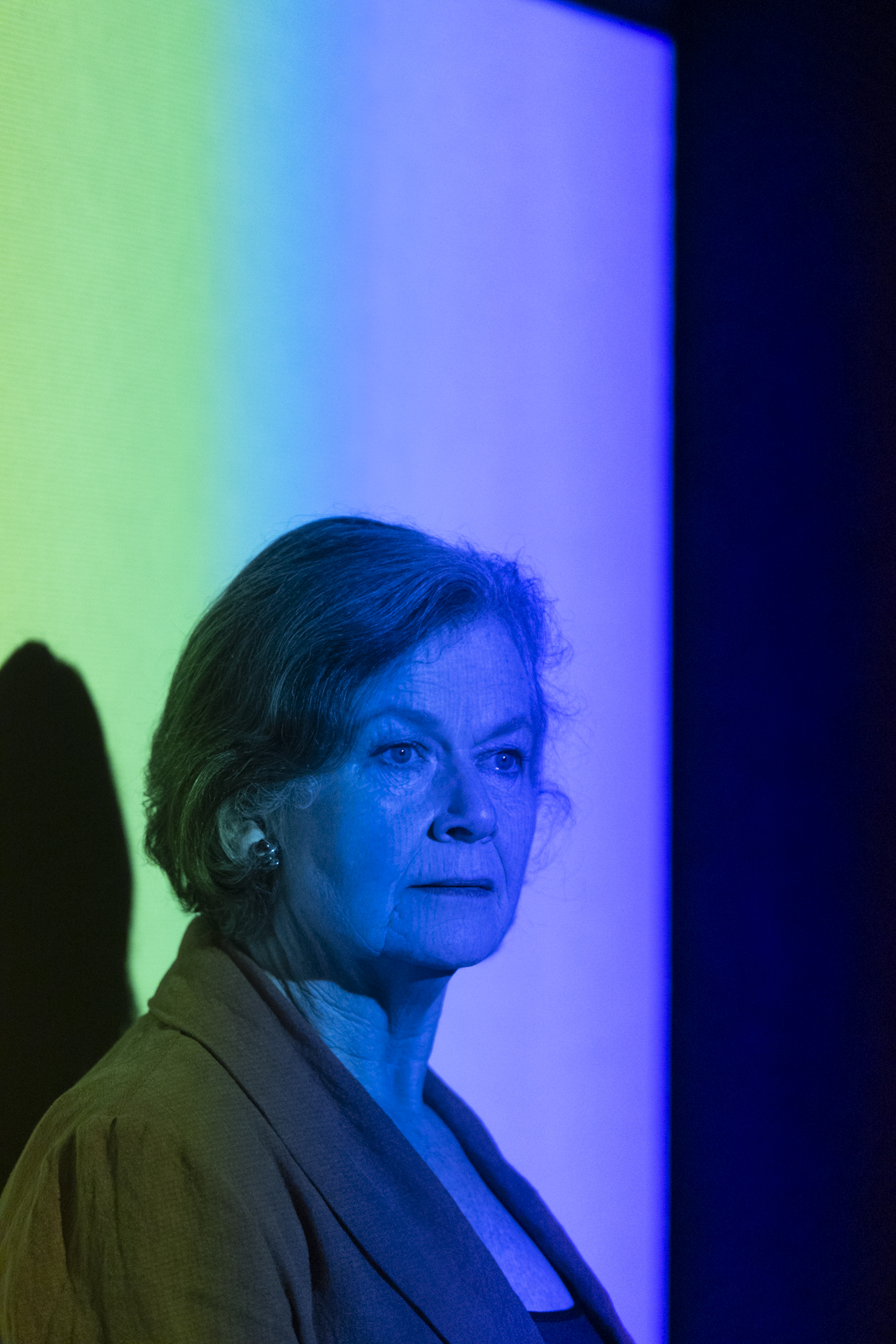

Venue: Wharf 1 Sydney Theatre Company (Walsh Bay NSW), Jan 8 – Feb 26, 2022

Playwright: Glace Chase

Director: Paige Rattray

Cast: Glace Chase, Josh McConville, Christen O’Leary, Anthony Taufa, Contessa Treffone

Images by Brett Boardman, Prudence Upton

Theatre review

Not only does Scotty have a highflying job on Wall Street, he lives in a US$3.5 million Tribeca loft, and is about to marry a Birkin-toting Kymberly. Everything looks to be peachy keen, but on the inside, he is a complete mess. The only saving grace is his secret affair with trans entertainer Dexie, but Scotty relegates the sole joy of his existence to the dark allegorical closet, afraid that the truth will destroy all.

Glace Chase’s Triple X tells an age-old story, but such is the severity of its associated taboo, that it feels like we are taking this conversation to the public domain, for the very first time. Chase’s writing is intricate and insightful, replete with splendid wit and a generosity of spirit that allows her show its wide appeal. The depth of honesty she is able to access for the play, is so confronting it feels almost self-sacrificial. The result of course, is the initiation of a big and necessary discussion, that is crucial to the well-being of trans people everywhere.

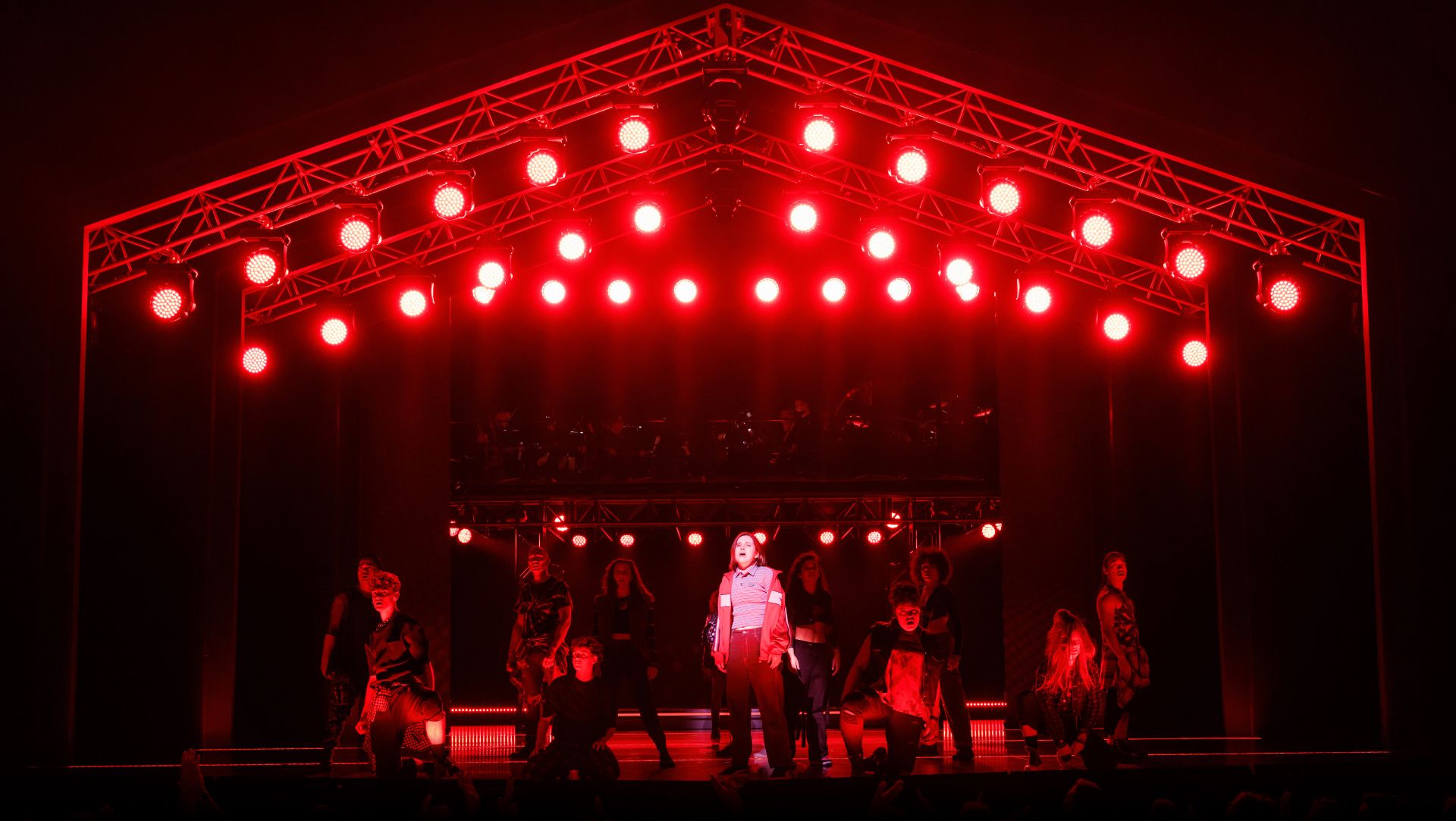

The show is given vibrant and taut direction by Paige Rattray, who makes the near three hours of Triple X feel a mere blink of an eye. The comedy is wild and raucous, yet bears an unmistakeable sense of sophistication. The deconstruction and analysis of ideas, are accomplished with admirable thoroughness. For all the irony and sarcasm dripping off of Triple X, there is thankfully no ambiguity to the important message it imparts.

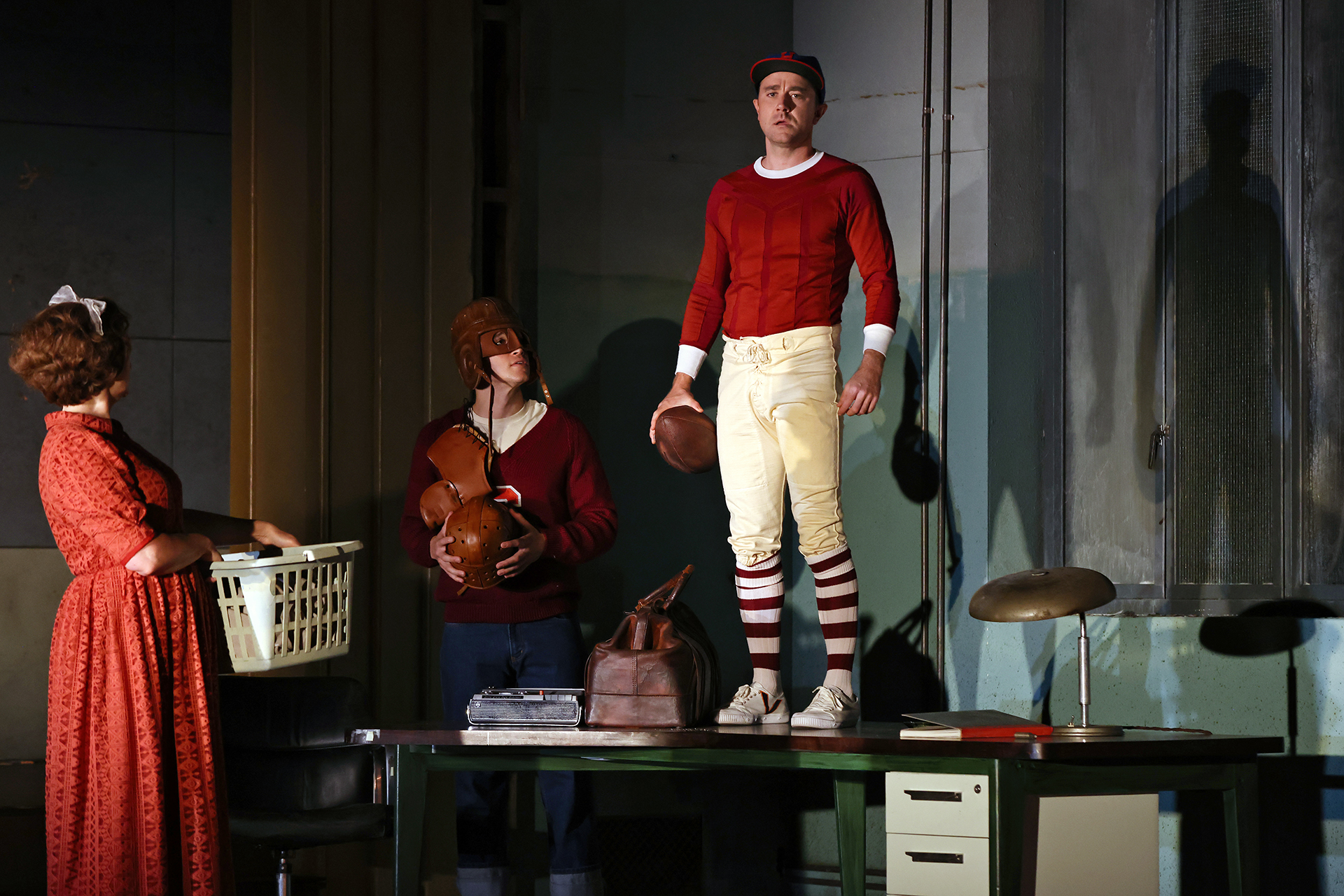

Designer Renée Mulder establishes on the stage, a versatile and highly functional set that provides a wealth of possibilities, whilst making Scotty’s apartment look every bit the million dollar listing that it aims to depict. Costumes are convincingly assembled, with several of Dexie’s more flamboyant outfits demonstrating great style and humour. Light by Ben Hughes too, add colour and texture that wonderfully enhance the mood of each scene.

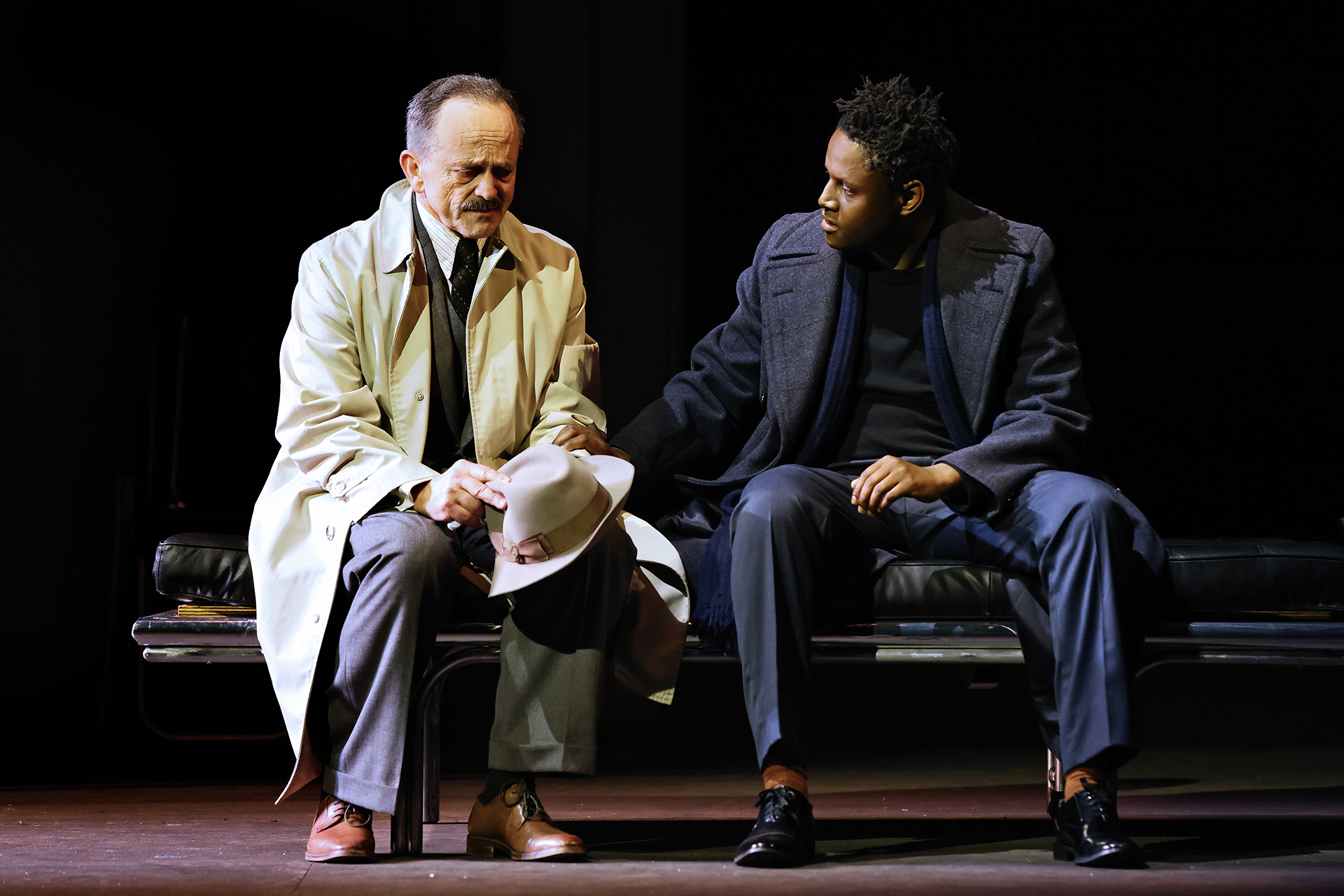

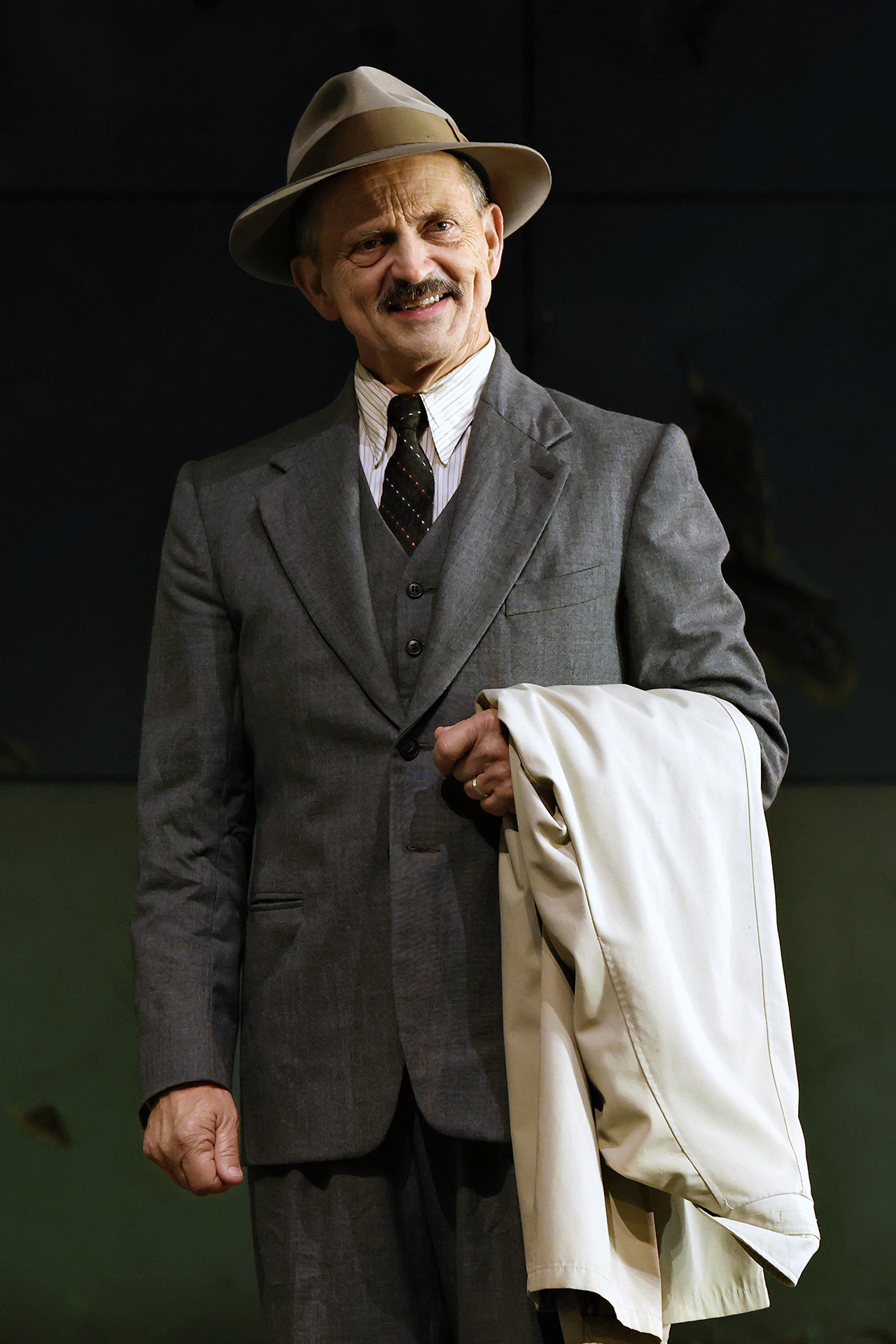

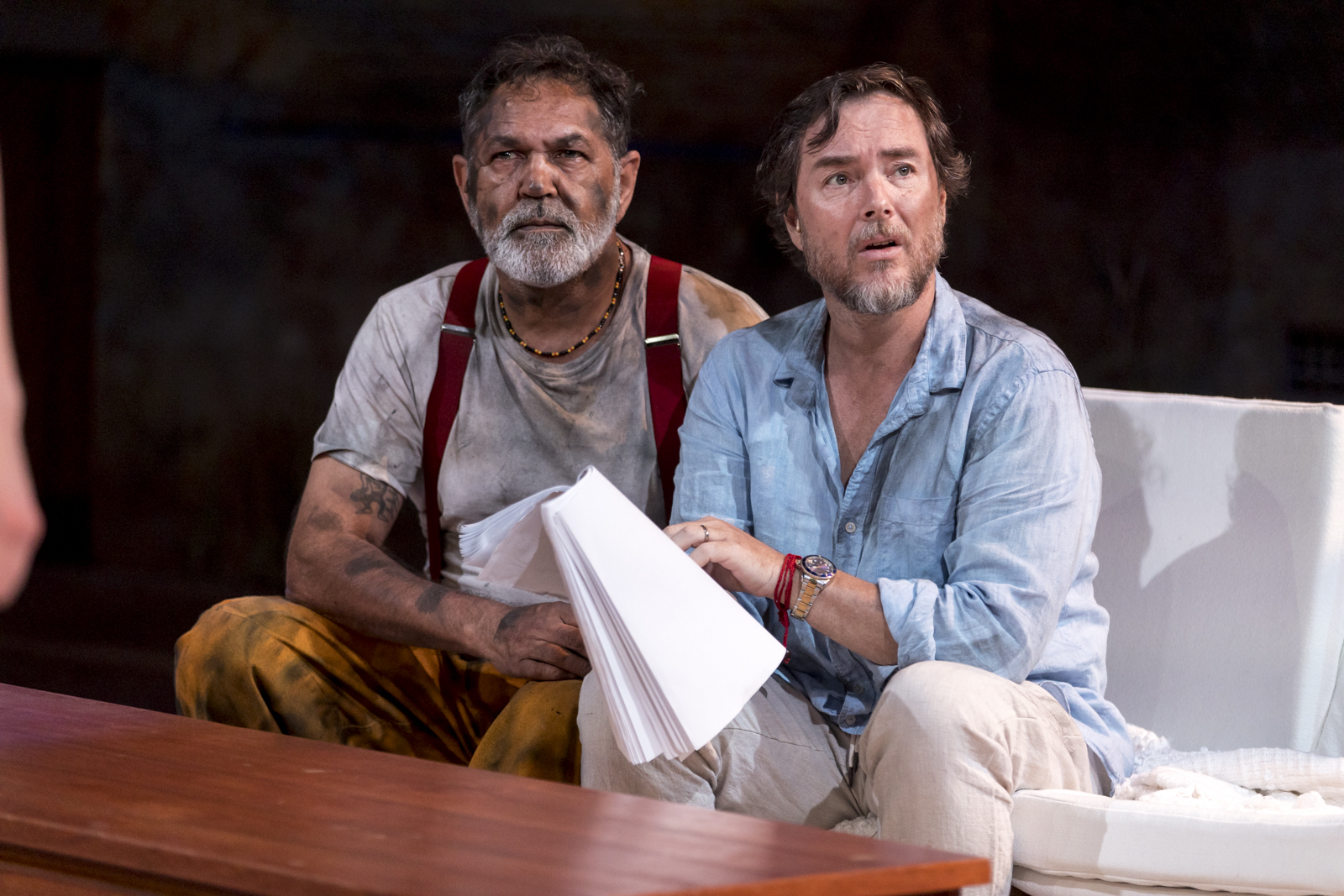

Chase herself plays Dexie, the scruffy warrior from clubland, and provocateur whose very presence insists the truth be out. The uncompromising authenticity that Chase brings to the role, is the lynchpin of the entire exercise. She makes us fall in love with Dexie, and respond with appropriate outrage, at the injustices that befall her. Josh McConville scintillates as Scotty, with boundless energy, both physical and emotional, to convey the frenzied discontentment that the character goes through in every waking moment.

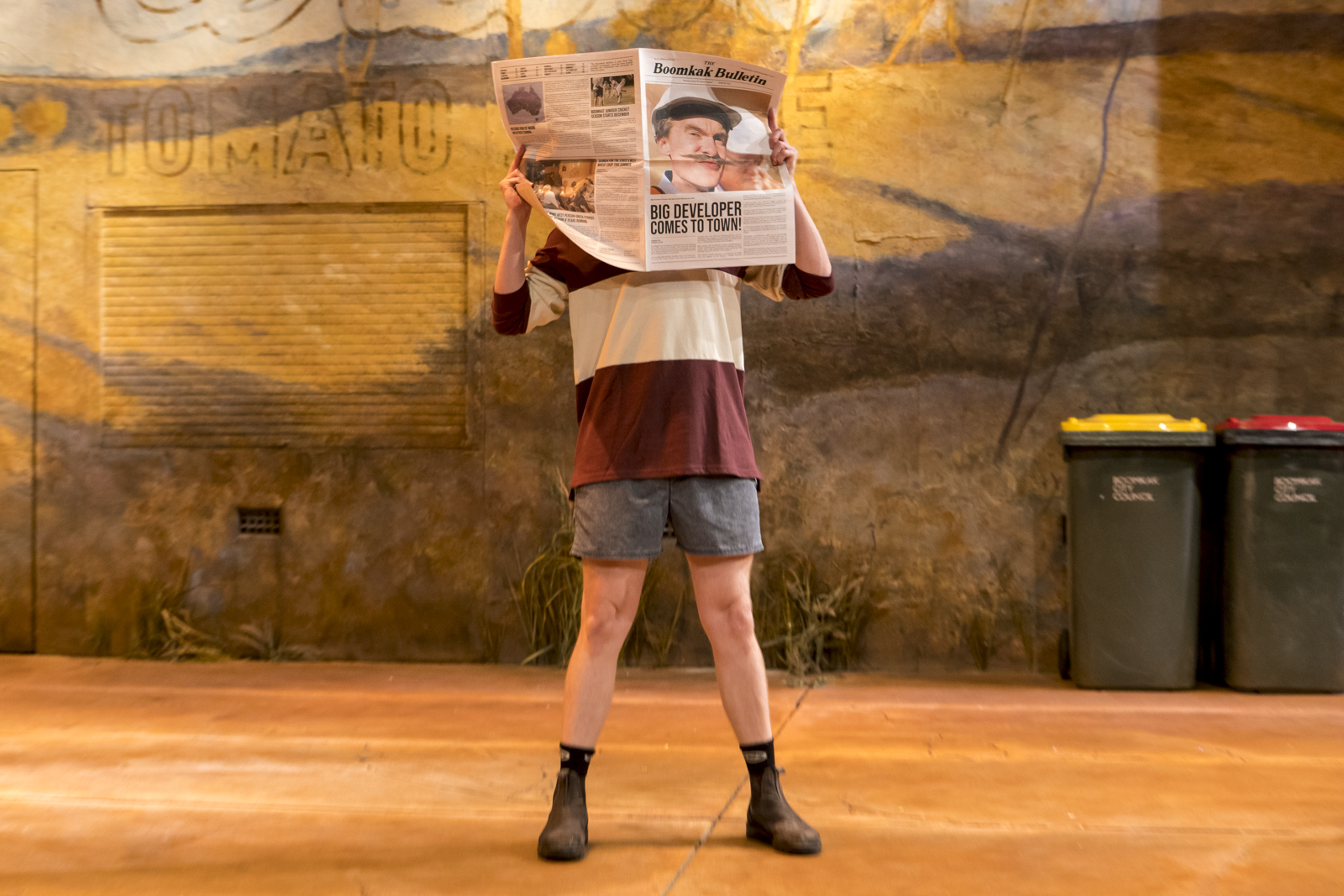

Similarly full of vigour is Christen O’Leary, whose unforgettable performance as Deborah, proves an unequivocal highlight of the production. Captivating and irresistibly funny, yet able to bring sincerity to her work, O’Leary is truly remarkable. Anthony Taufa and Contessa Treffone both create likeable personalities, who add dynamism and complexity to the story being told. The entire cast is passionate, with an infectious earnestness that really drive home the urgency of all that is being discussed.

The main thing that Triple X says, is that although there is nothing wrong with Dexie, and that she lives her life to the fullest of her abilities, the world around her is constantly trying to pull her down. Even when she finds love unexpectedly, the embarrassing predictability of a man’s cowardice, is determined to replace pleasure with misery, joy with anguish. Of course Dexie deserves love, but more than that, she deserves dignity, and the well-founded wisdom of knowing better.

For Scotty, the affair means much more than it does to Dexie. Trans women of a certain age have seen it all before, and there will always be plenty more fish in the sea, should one choose to partake in a never-ending revolving door of fleeting romances. On the other hand, for men like Scotty who know that intimacy with a trans woman, is part of their journey to true happiness, to lose a love could easily be an irrevocable error. Those who remain cowards shall find no peace, and those who relish in bravery certainly deserve no cowards.