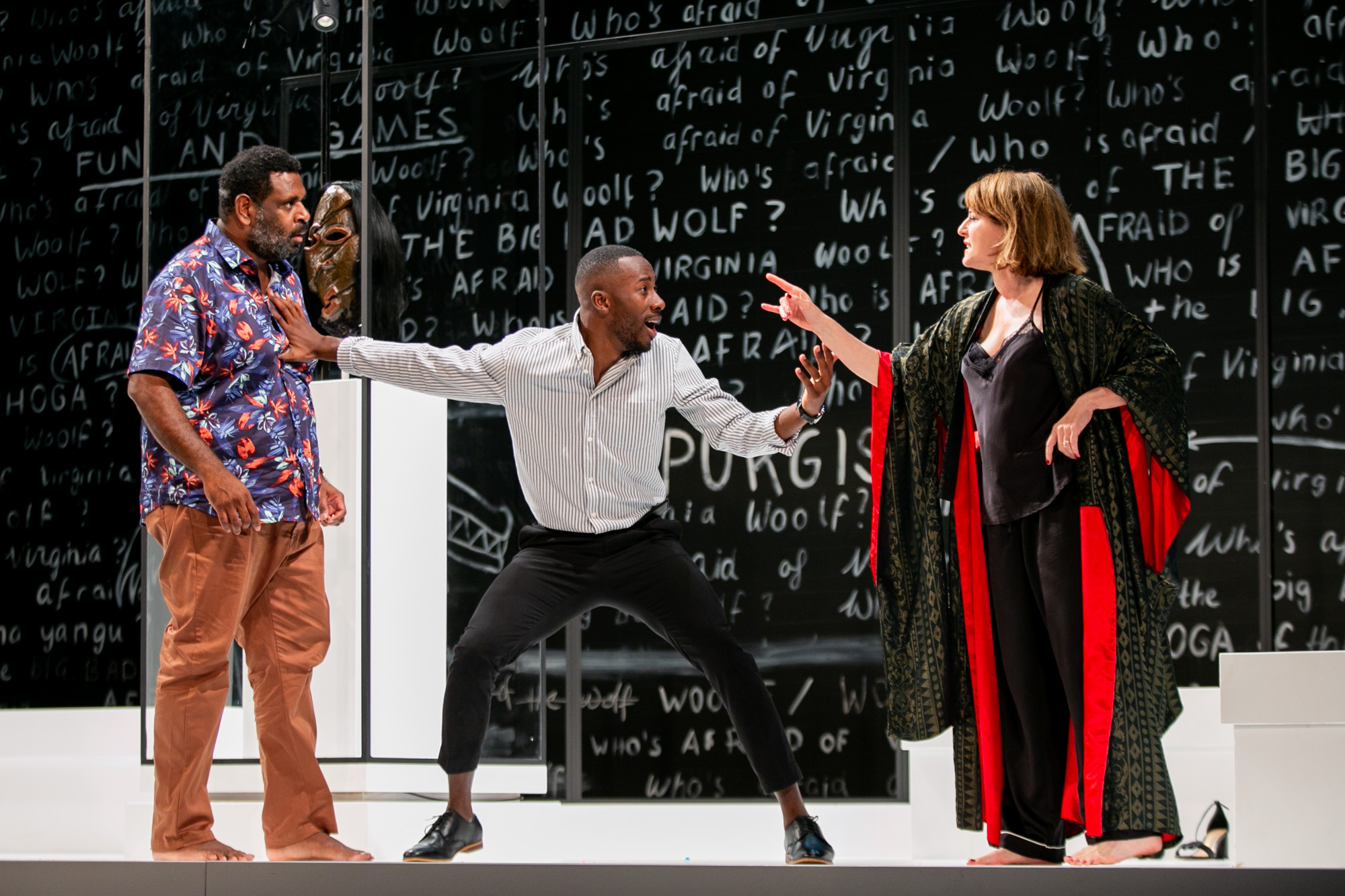

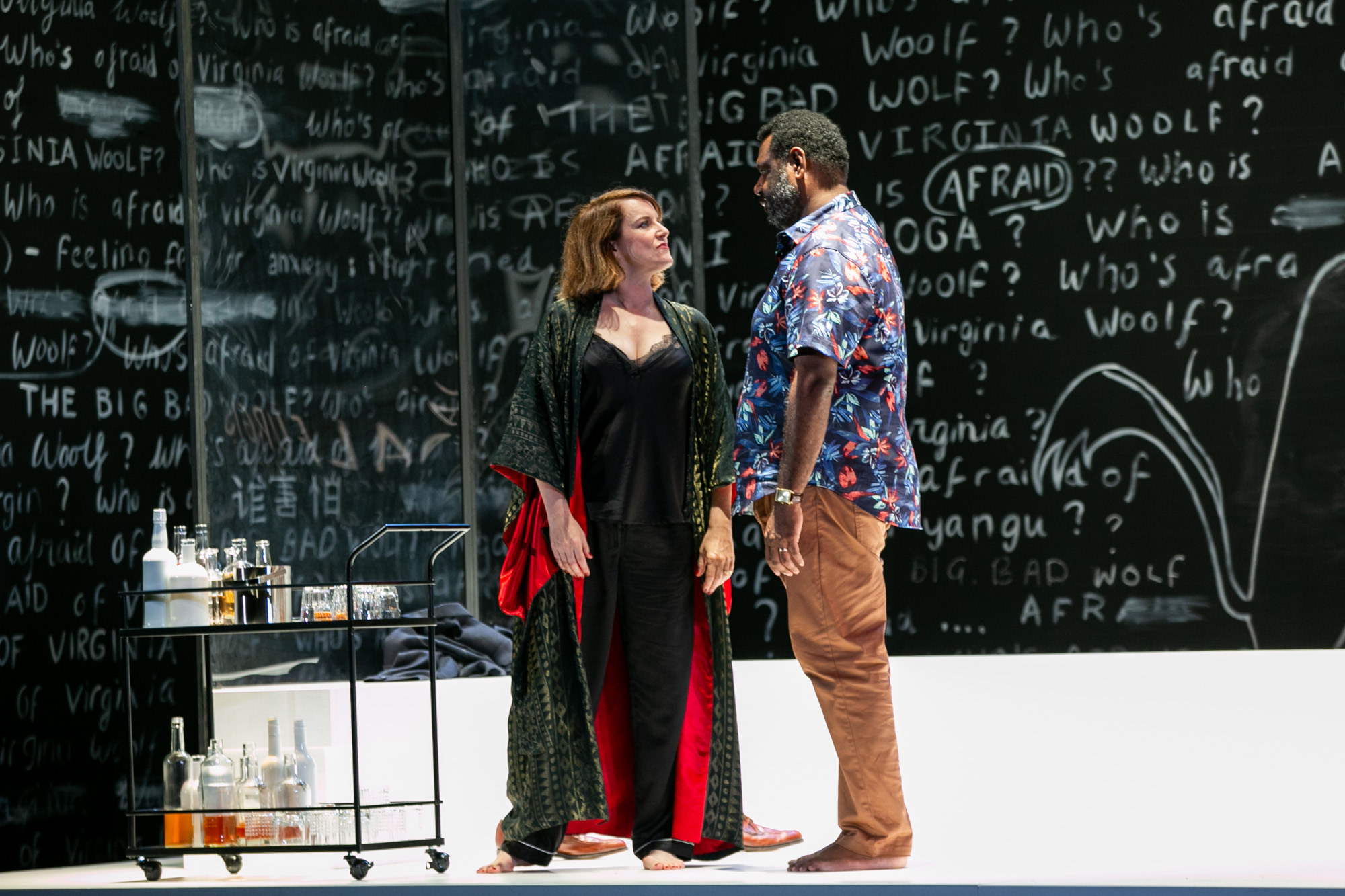

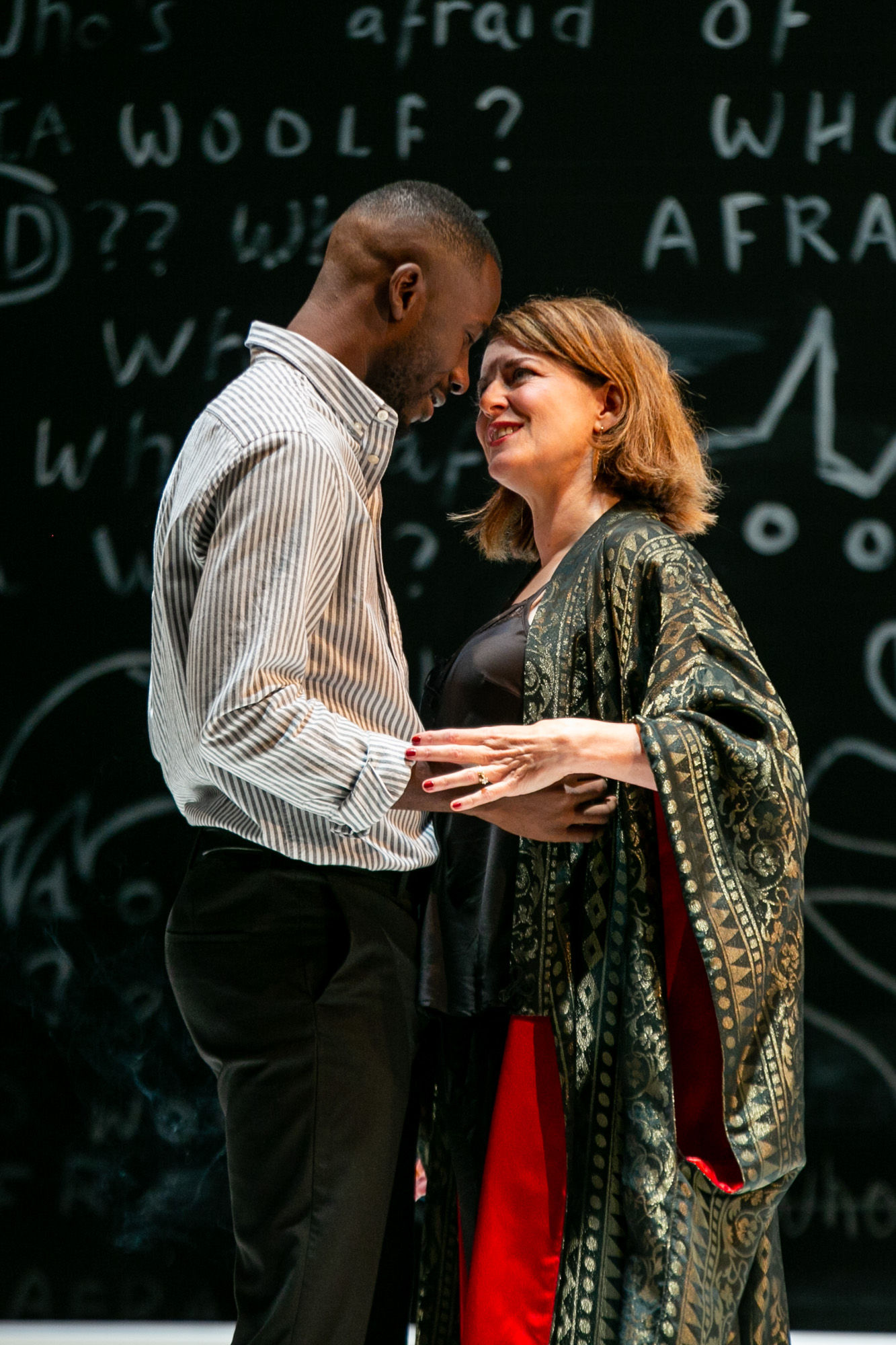

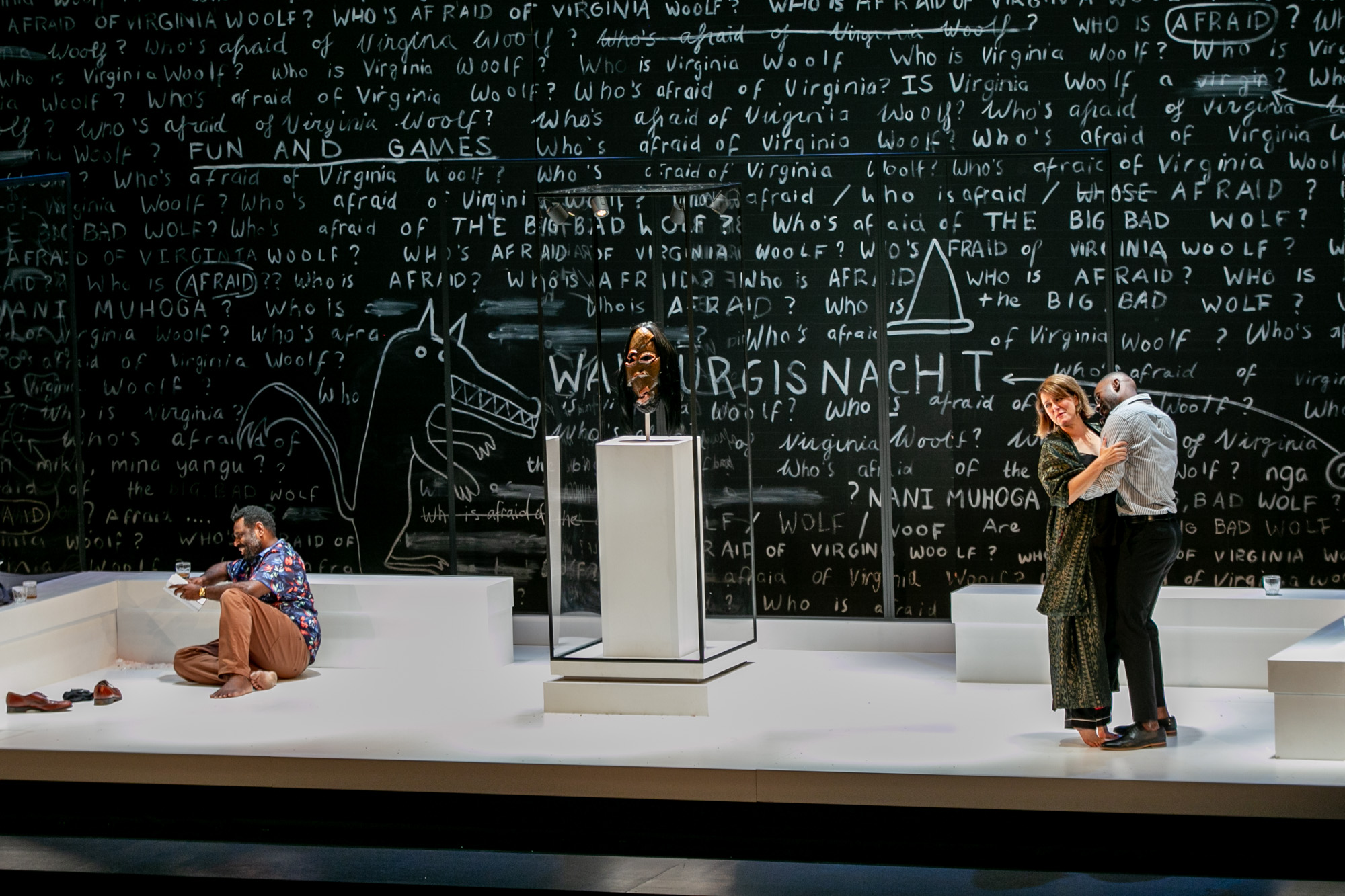

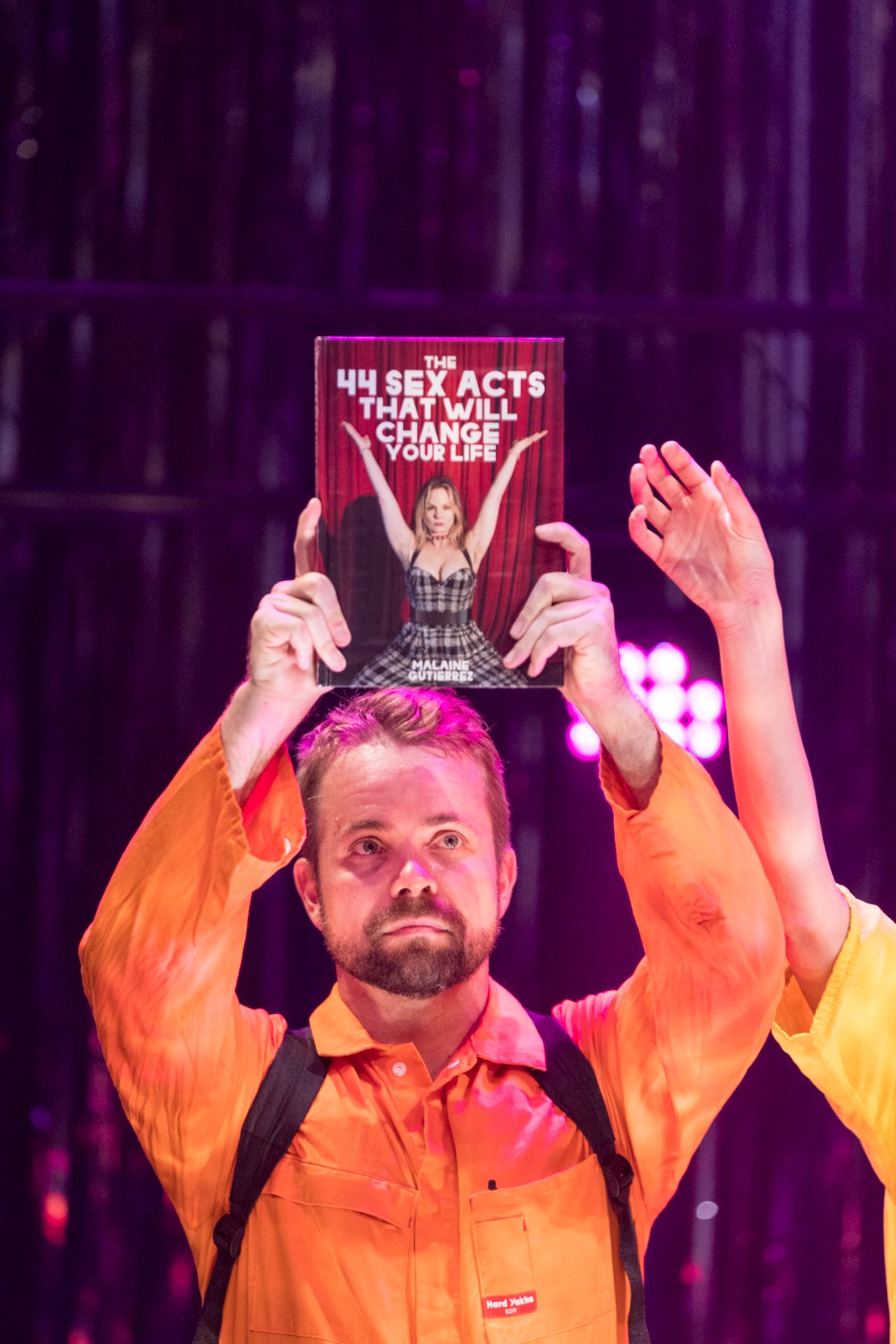

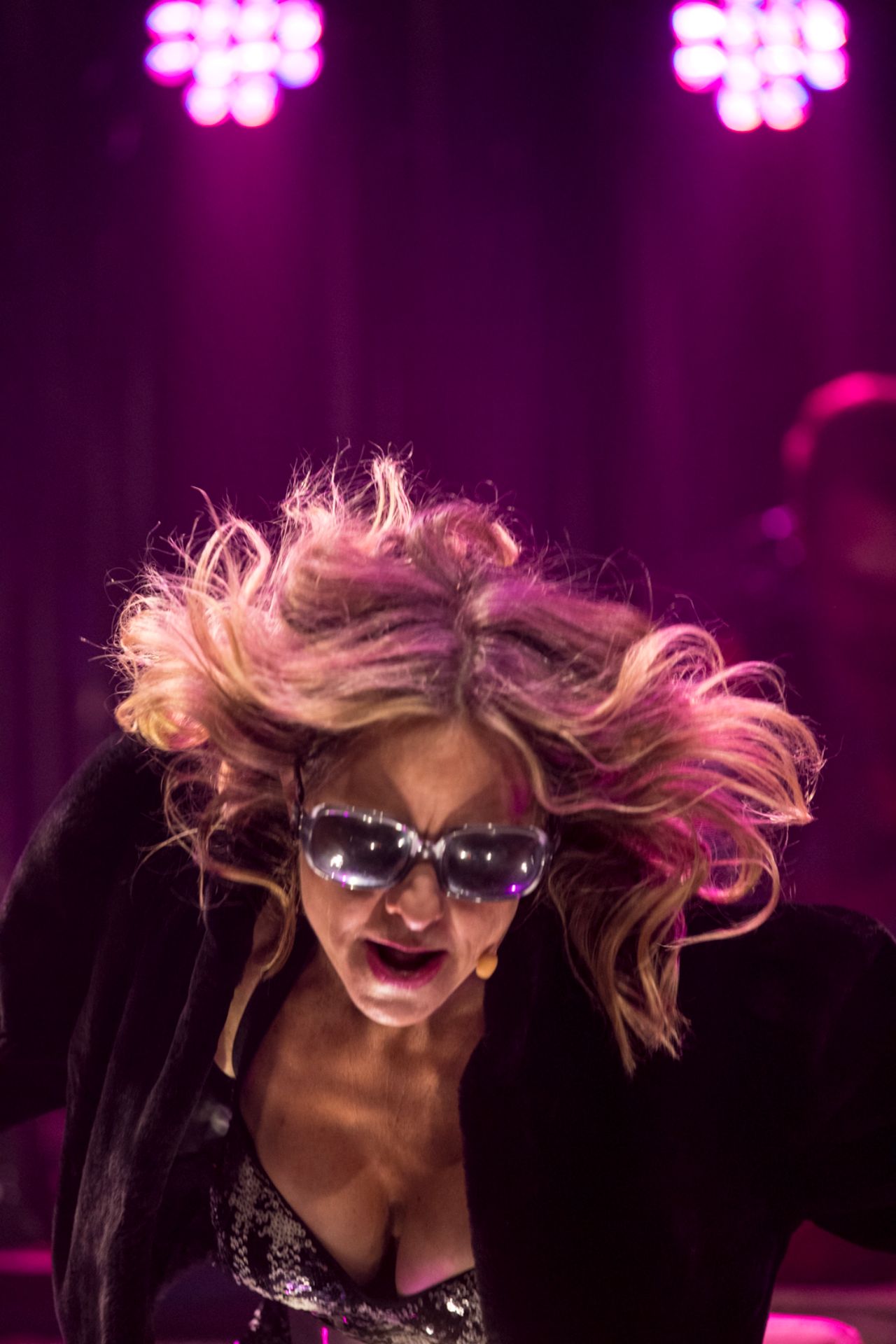

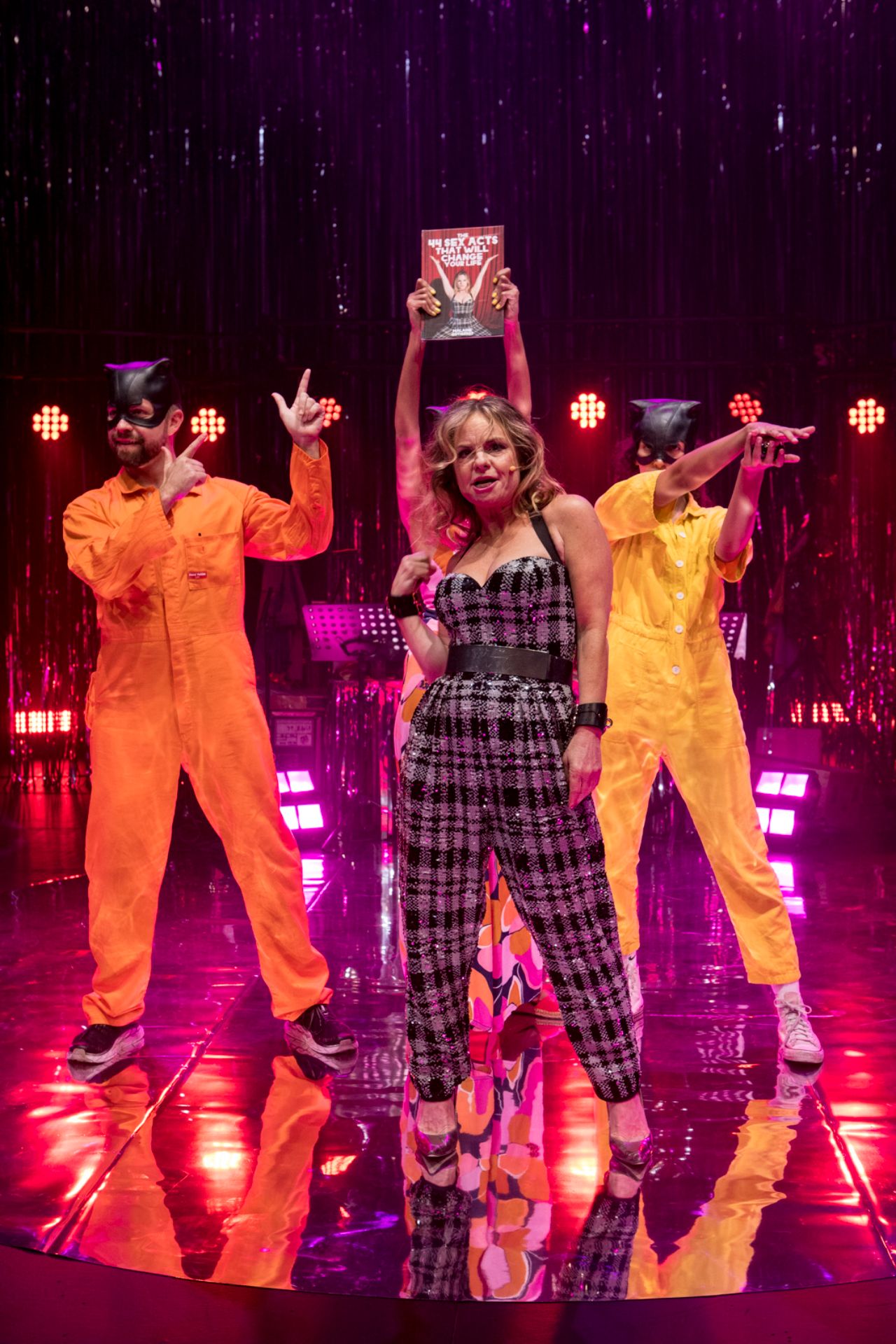

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Feb 13 – Mar 11, 2022

Music: Marvin Hamlish

Lyrics: Edward Kleban

Book: Nicholas Dante, James Kirkwood

Director: Amy Campbell

Cast: Max Bimbi, Molly Bugeja, Angelique Cassimatis, Ross Chisari, Nadia Coote, Tim Dashwood, Lachlan Dearing, Mackenzie Dunn, Maikolo Fekitoa, Adam Jon Fiorentino, Natalie Foti, Ashley Goh, Mariah Gonzalez, Brady Kitchingham, Madeleine Mackenzie, Rechelle Mansour, Natasha Marconi, Rubin Matters, Ryan Ophel, Tony Oxybel, Ethan Ritchie, Suzanne Steele, Harry Targett, Angelina Thomson

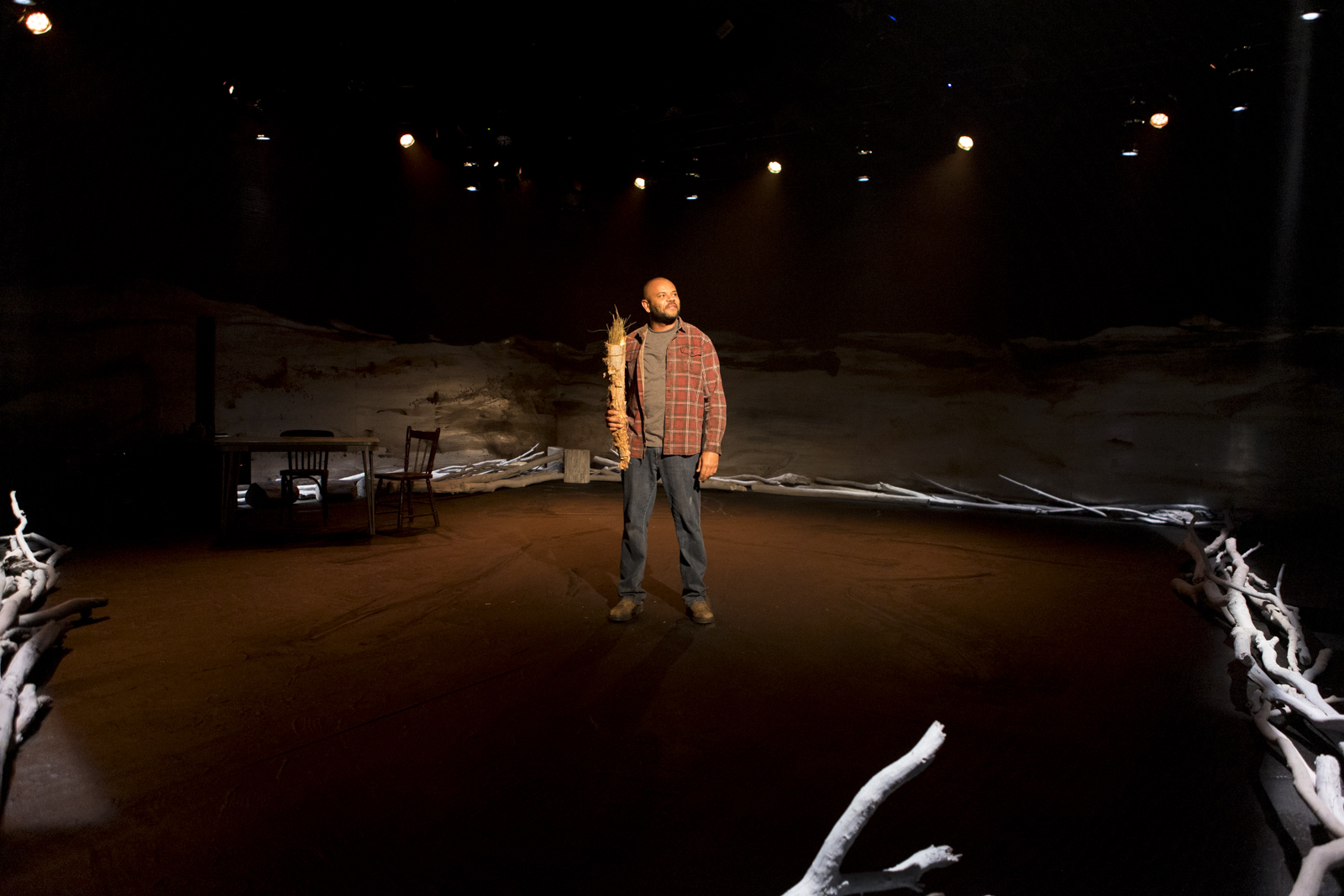

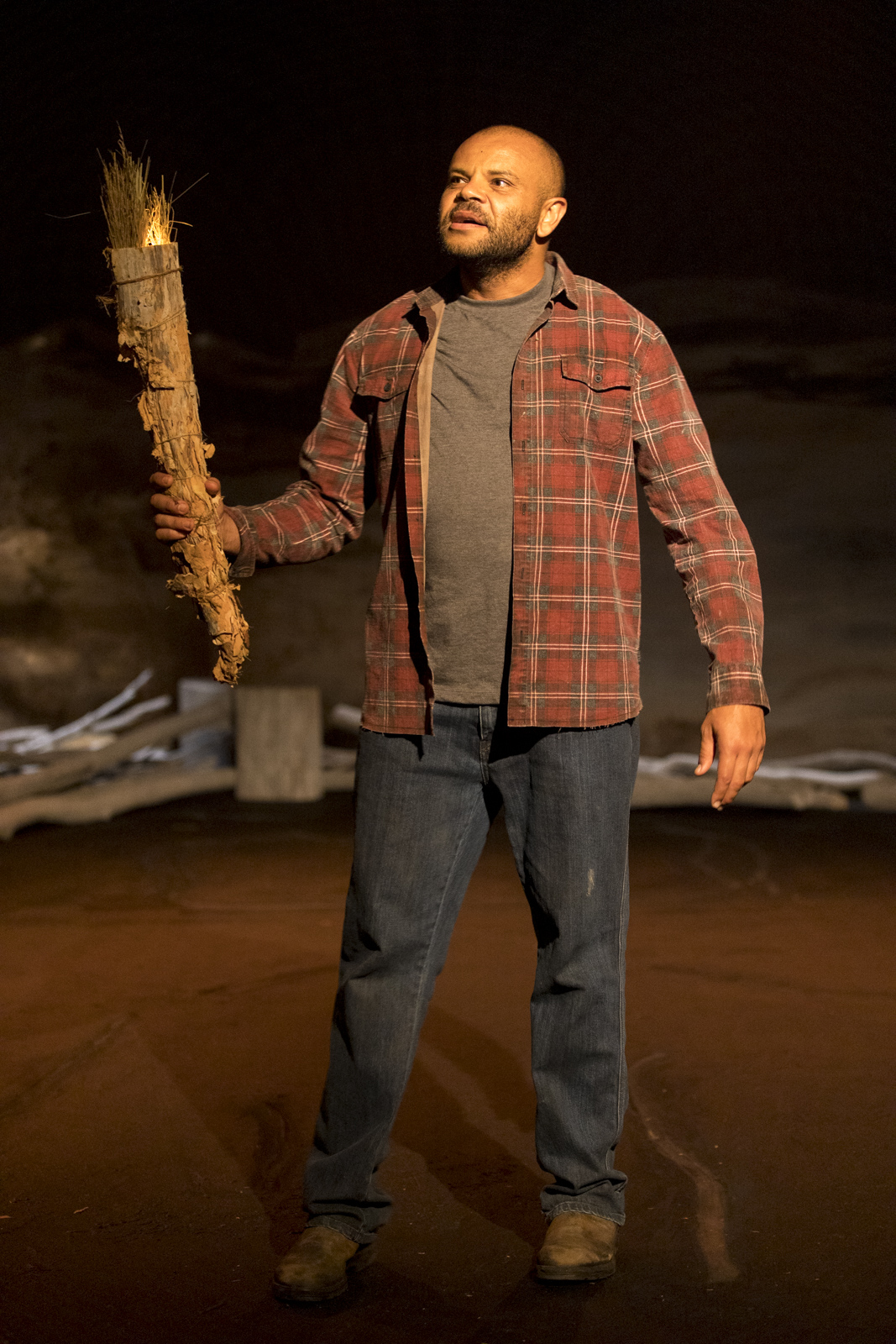

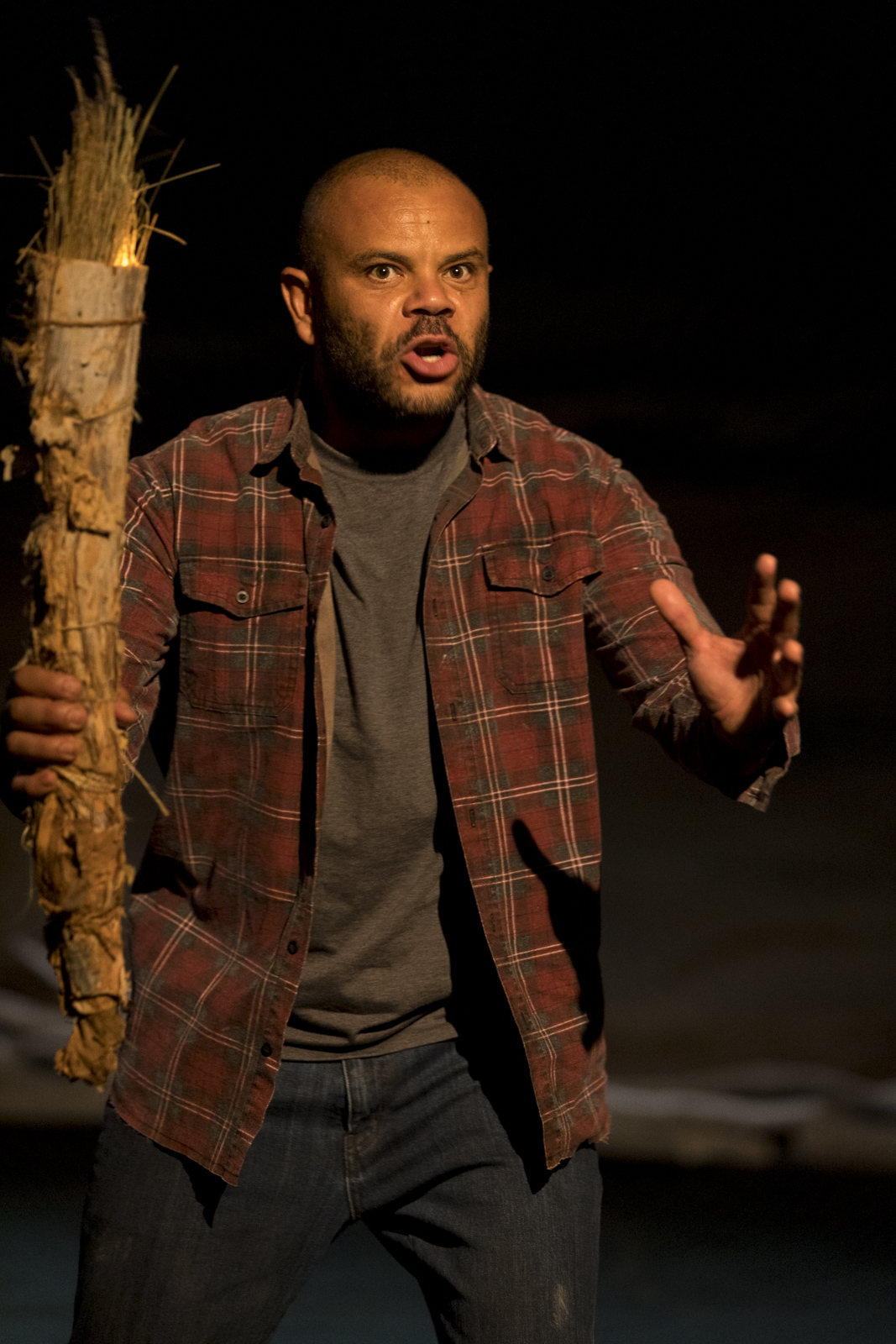

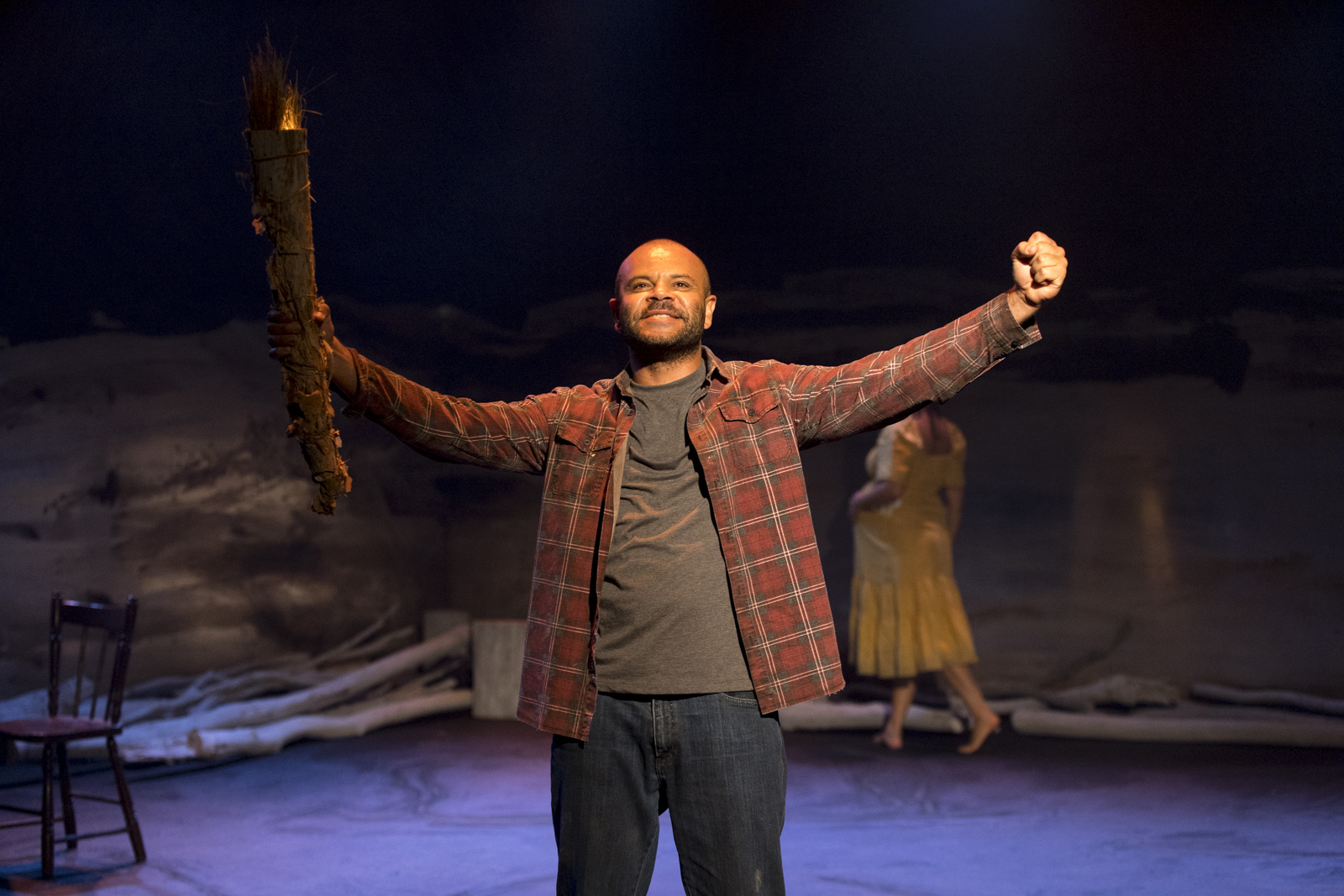

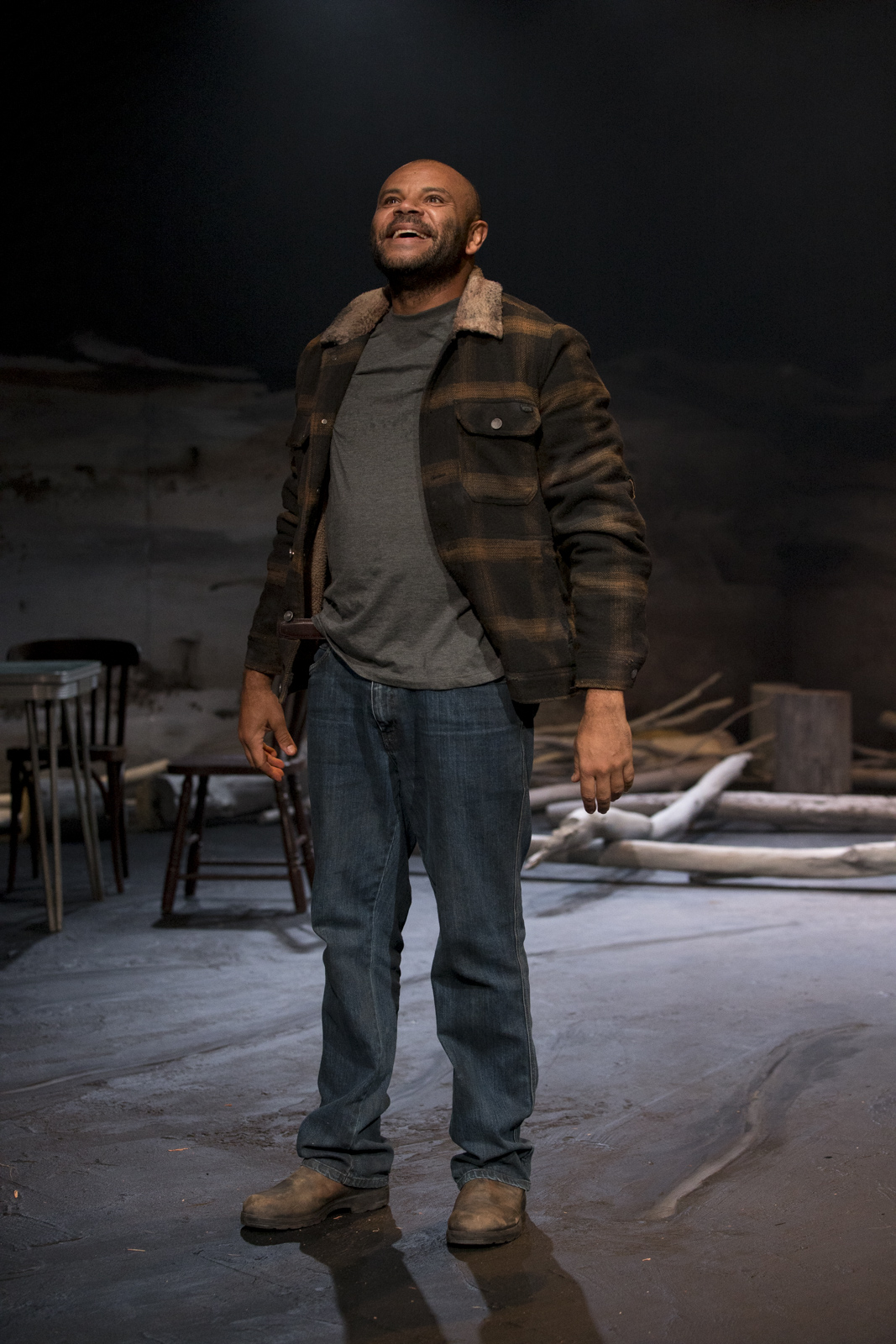

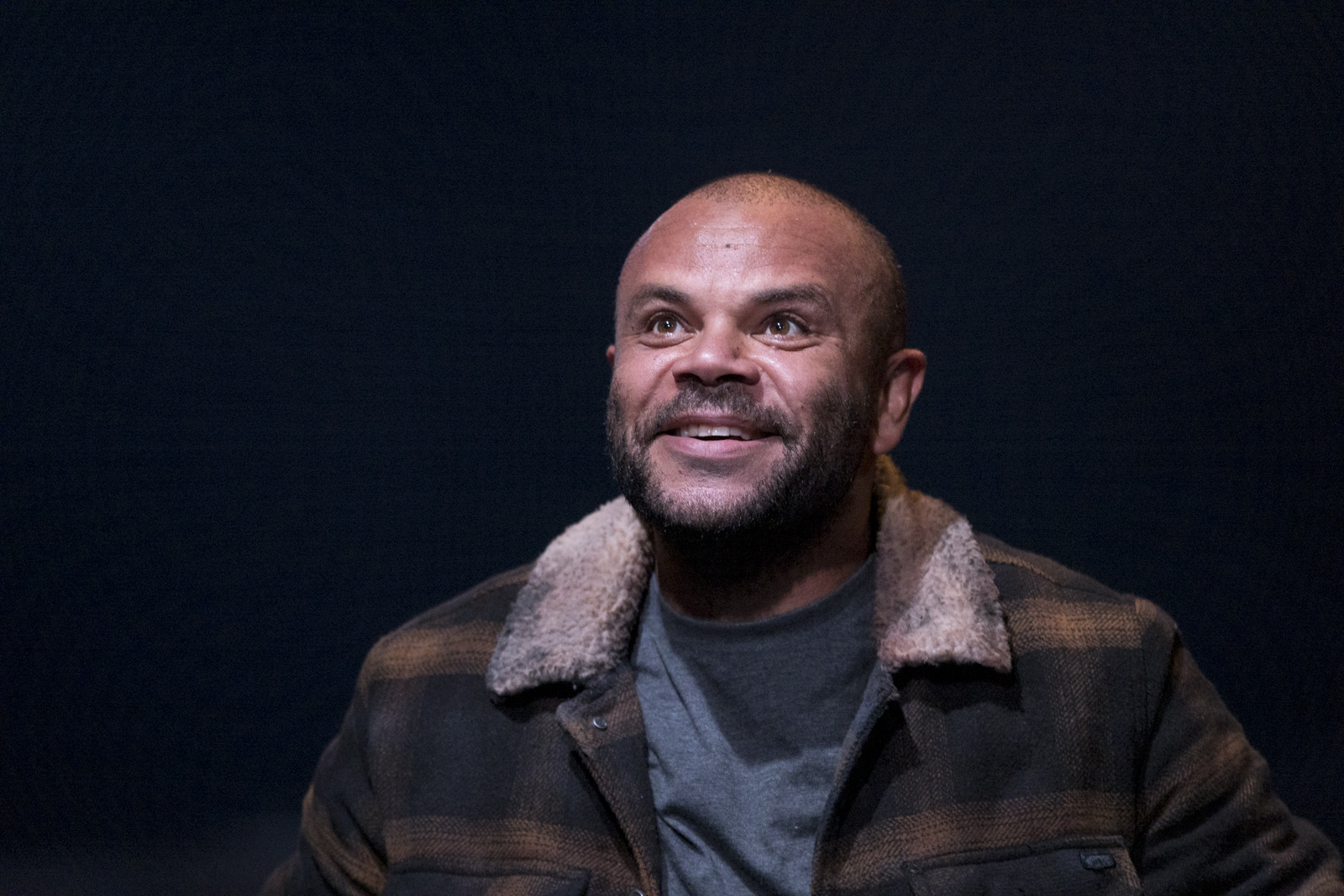

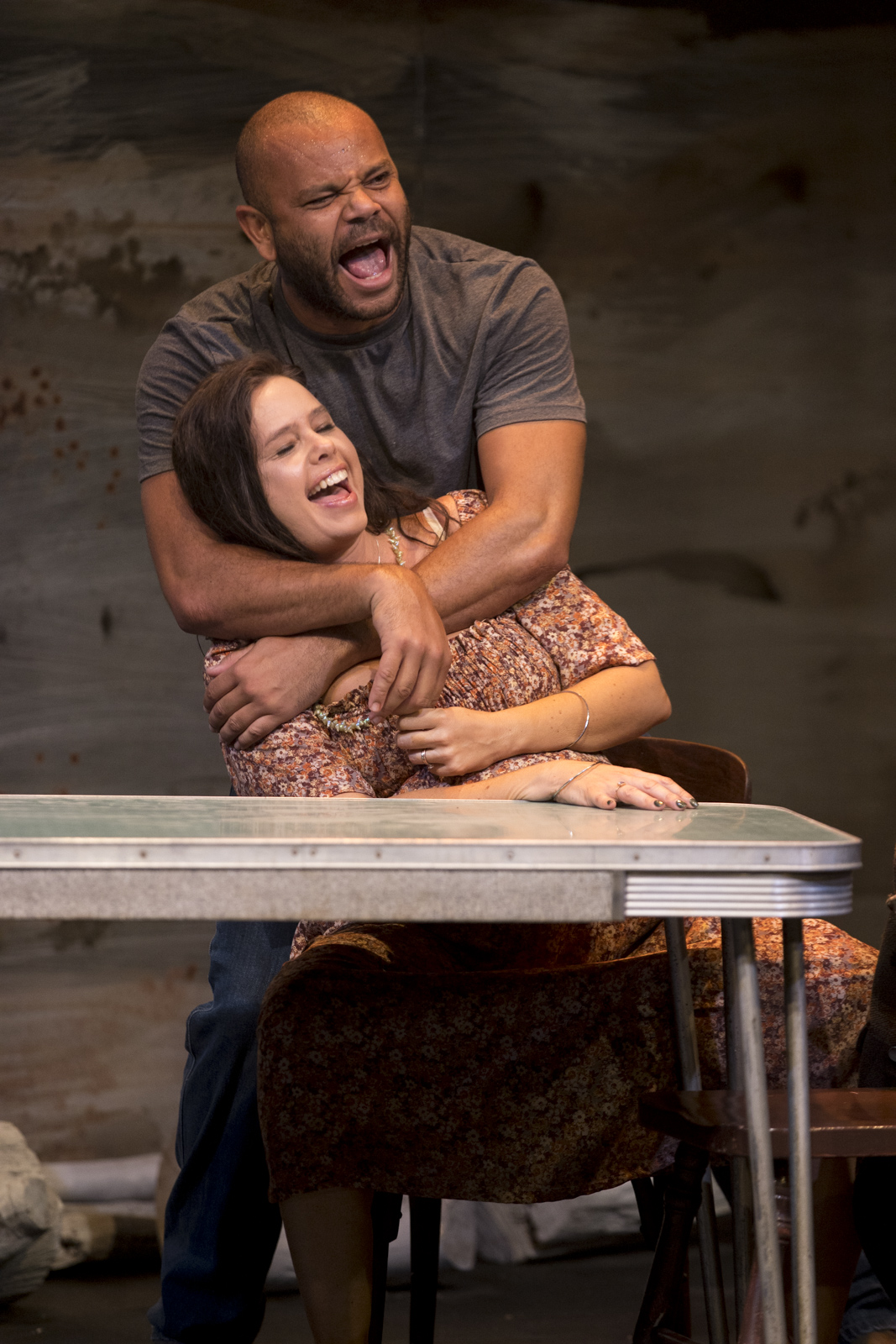

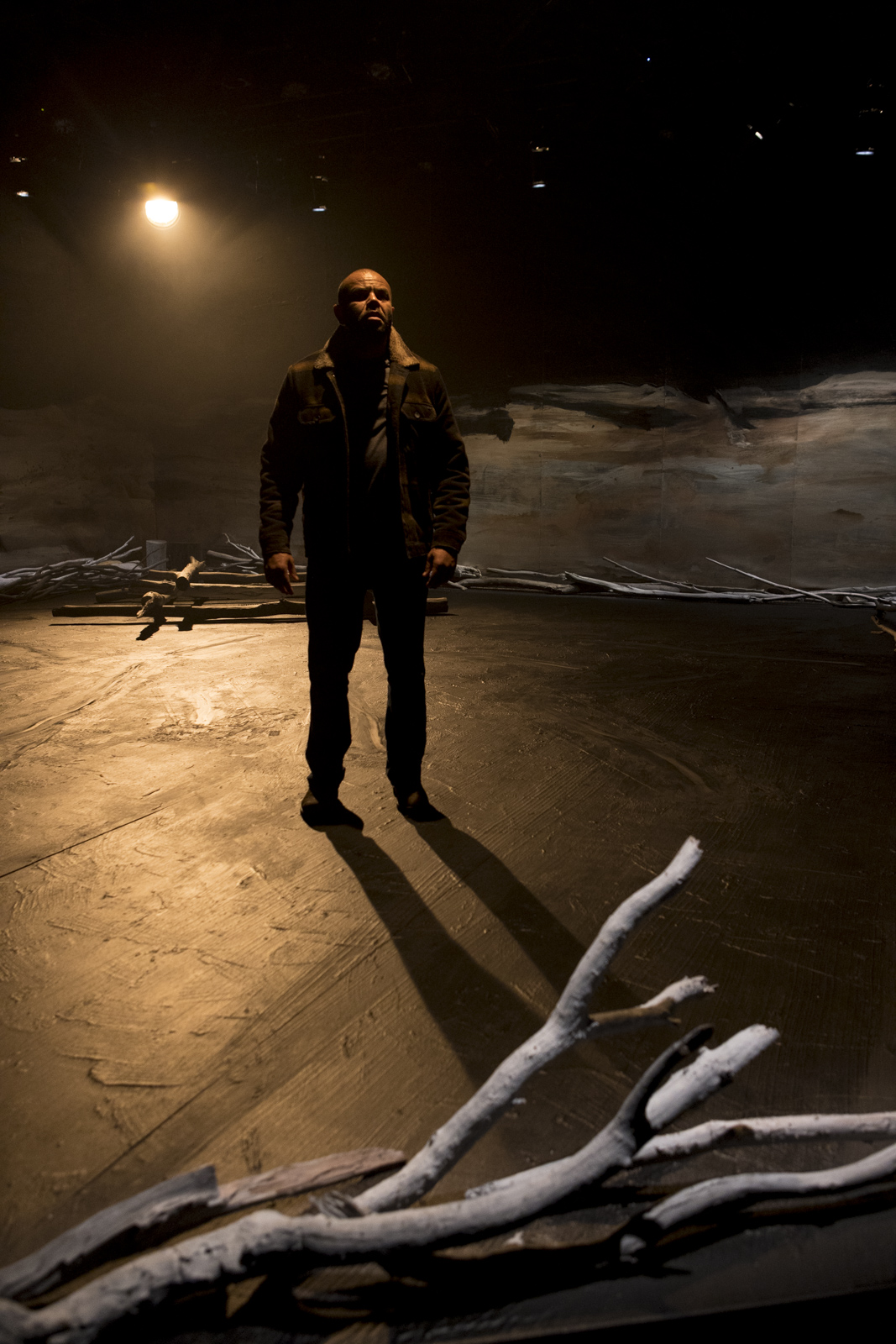

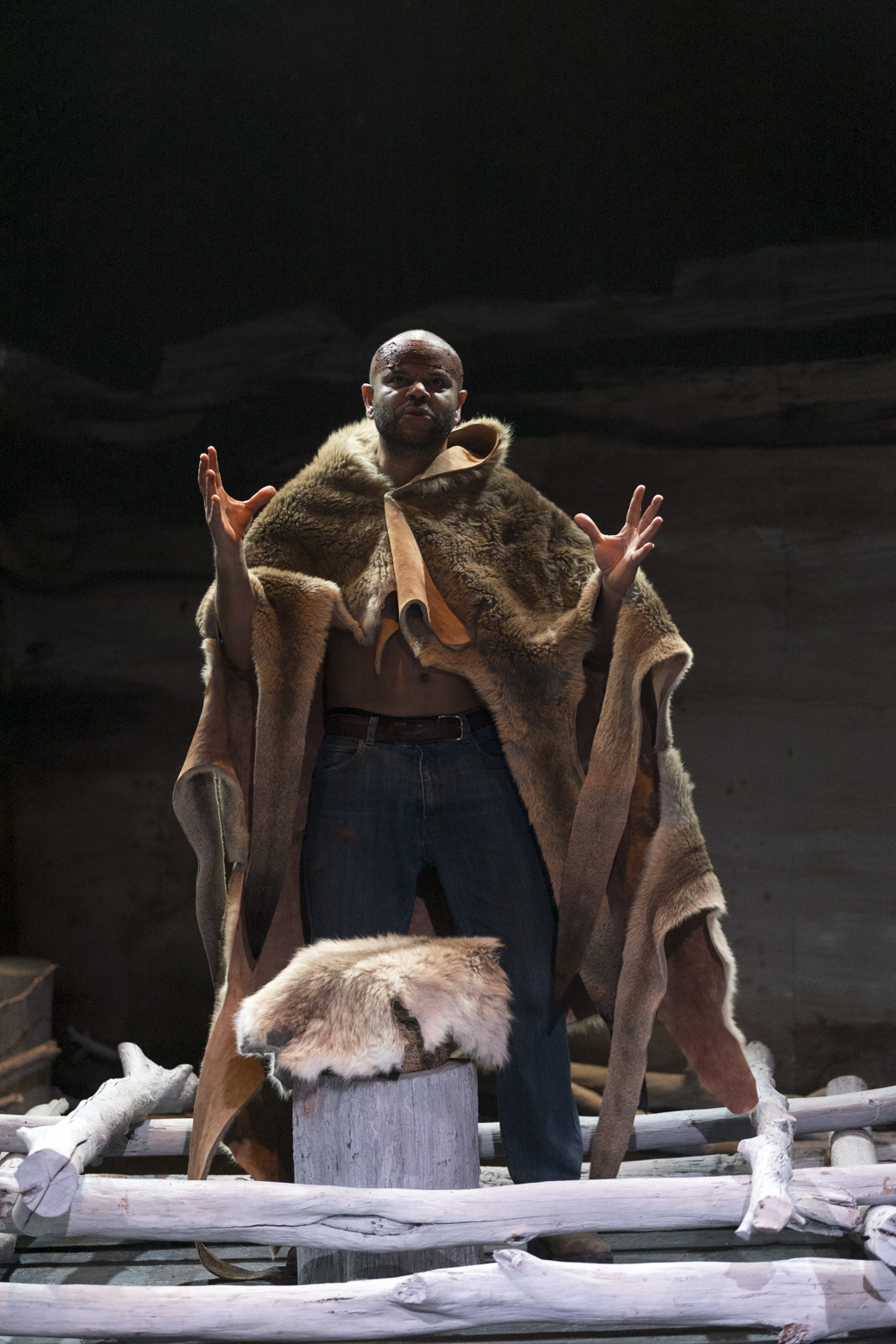

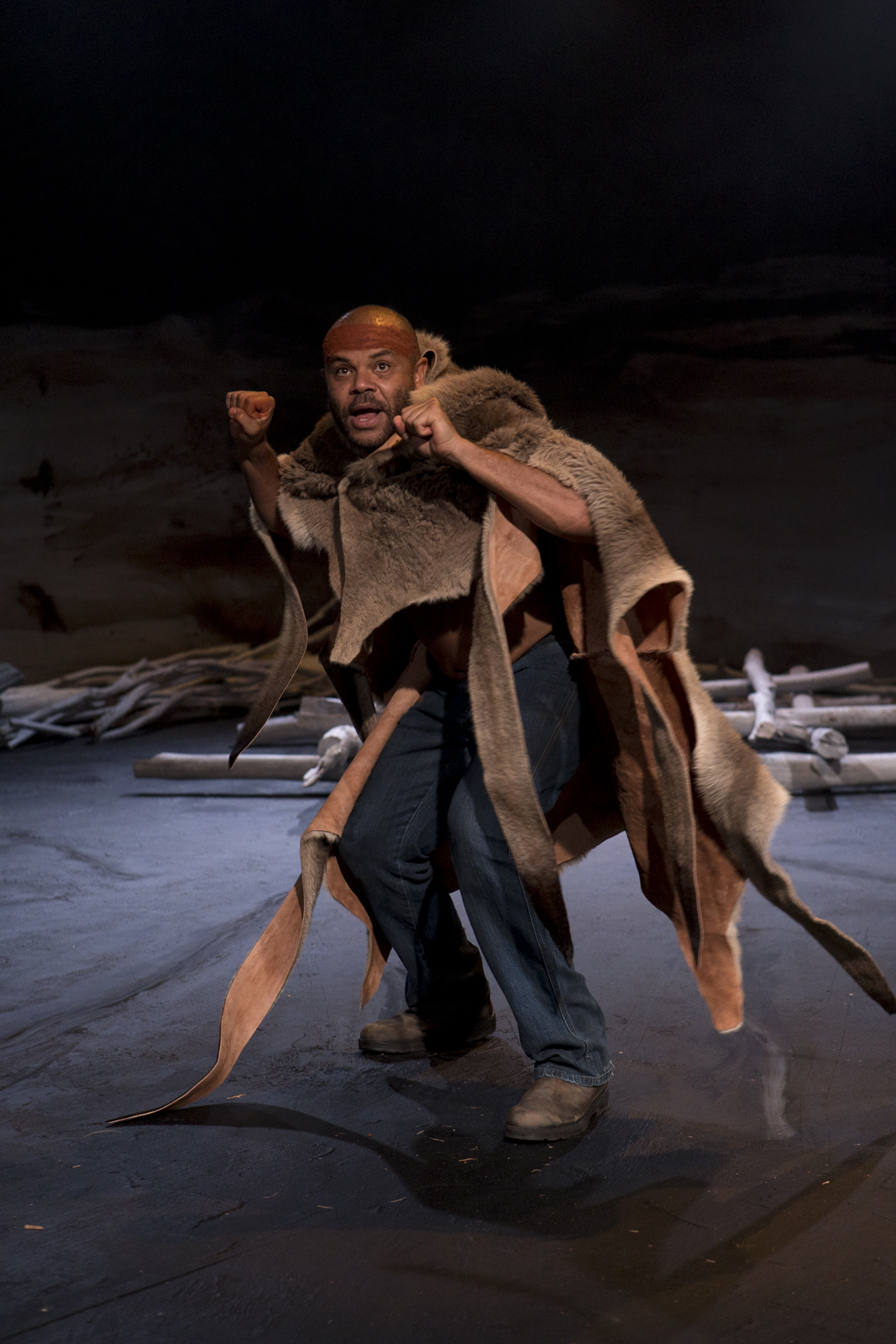

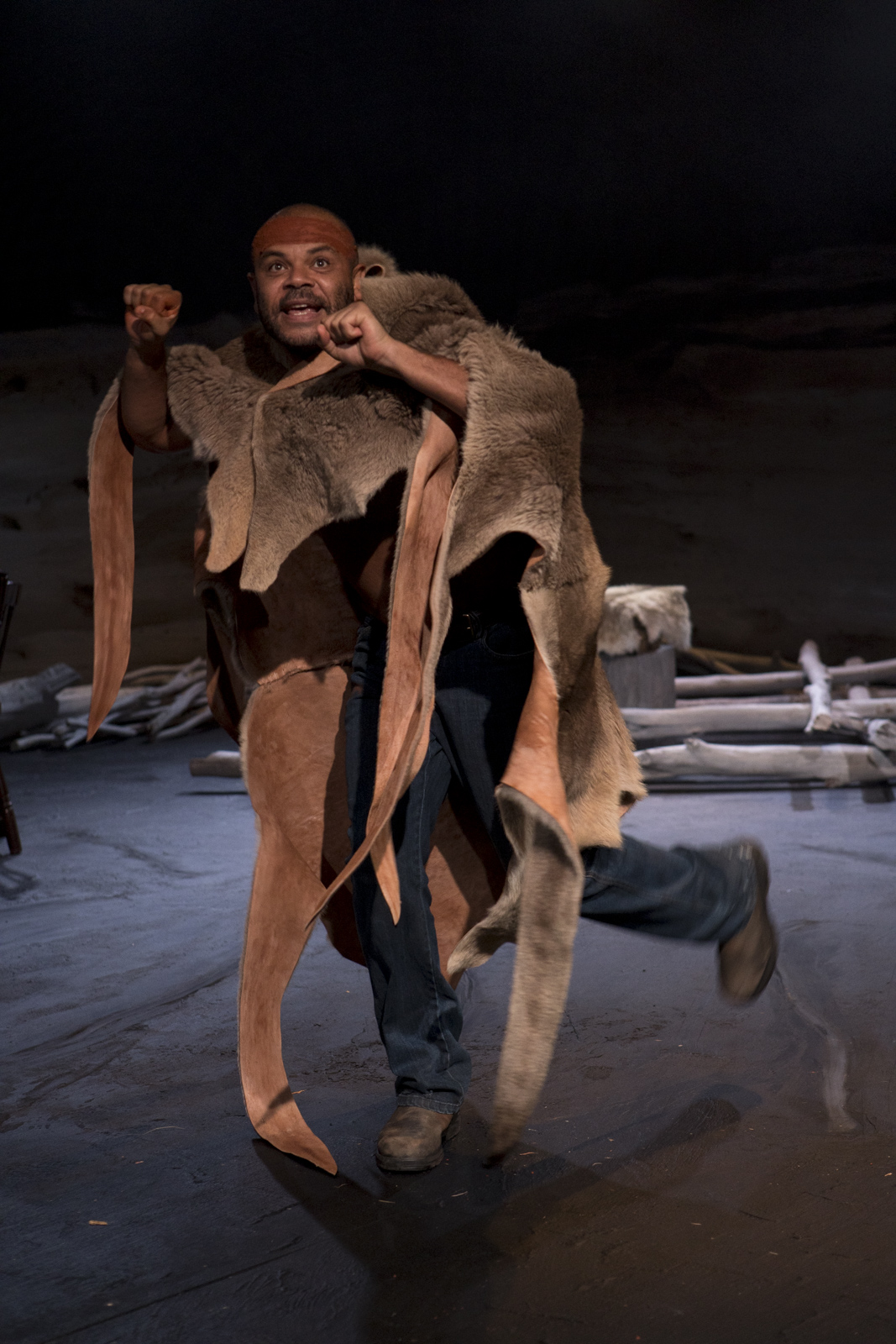

Images by Robert Catto

Theatre review

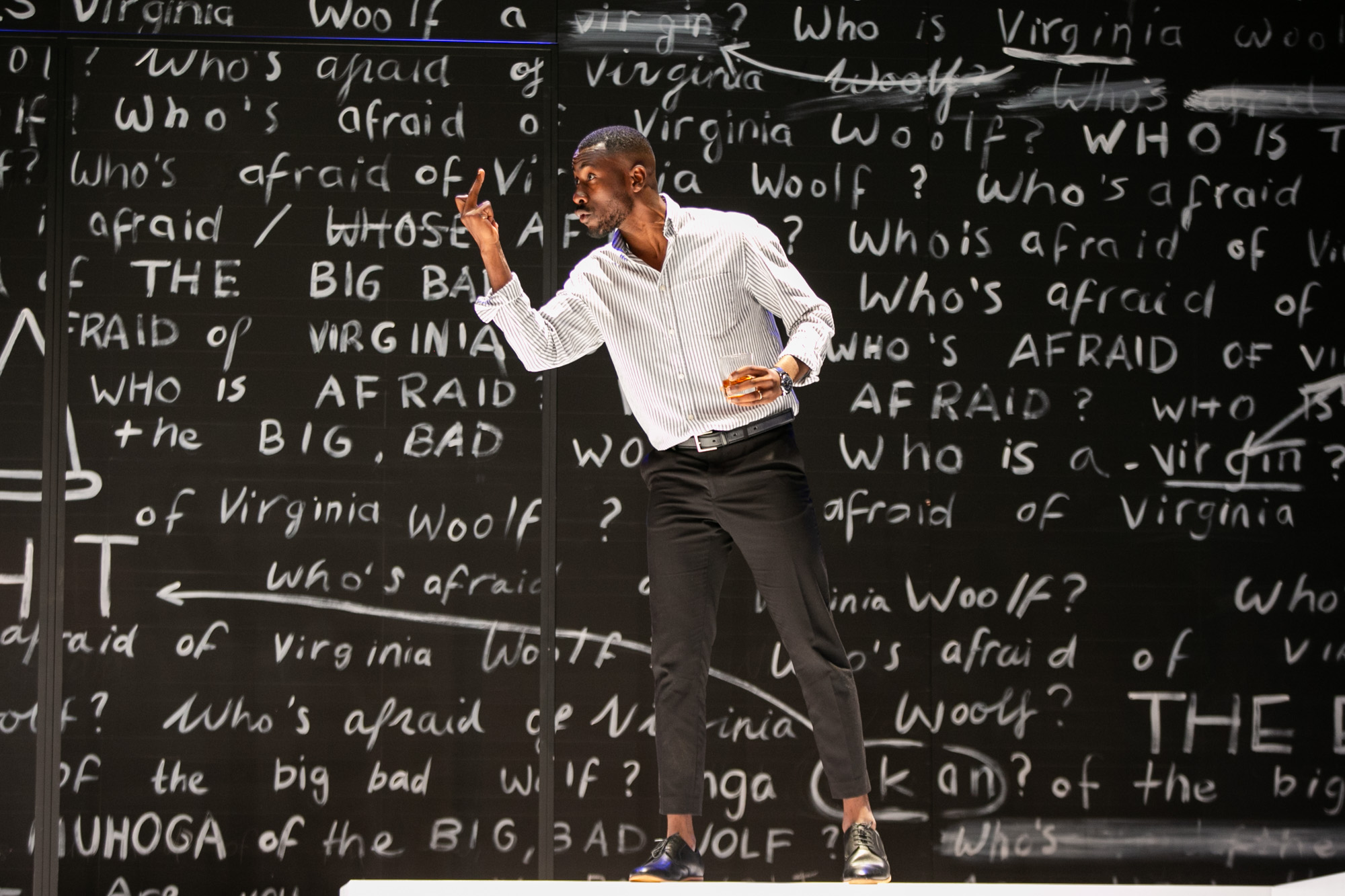

Originally conceived in 1975 by Michael Bennett, the legendary musical A Chorus Line involves an ensemble cast of nineteen, several unforgettable songs, and dance sequences that have become an indelible part of our collective cultural memory. It is the simple story about Broadway director Zach at a casting call, auditioning a throng of dancers, for eight places in his new show. A Chorus Line is a tribute to the innumerable artists who have dedicated their lives to a passion, that never yields commensurate rewards. The show is an opportunity for talents to show their wares, with each member of cast provided individual moments of glory, as well as working in groups for some of the most exciting and complicated choreography in the musical format.

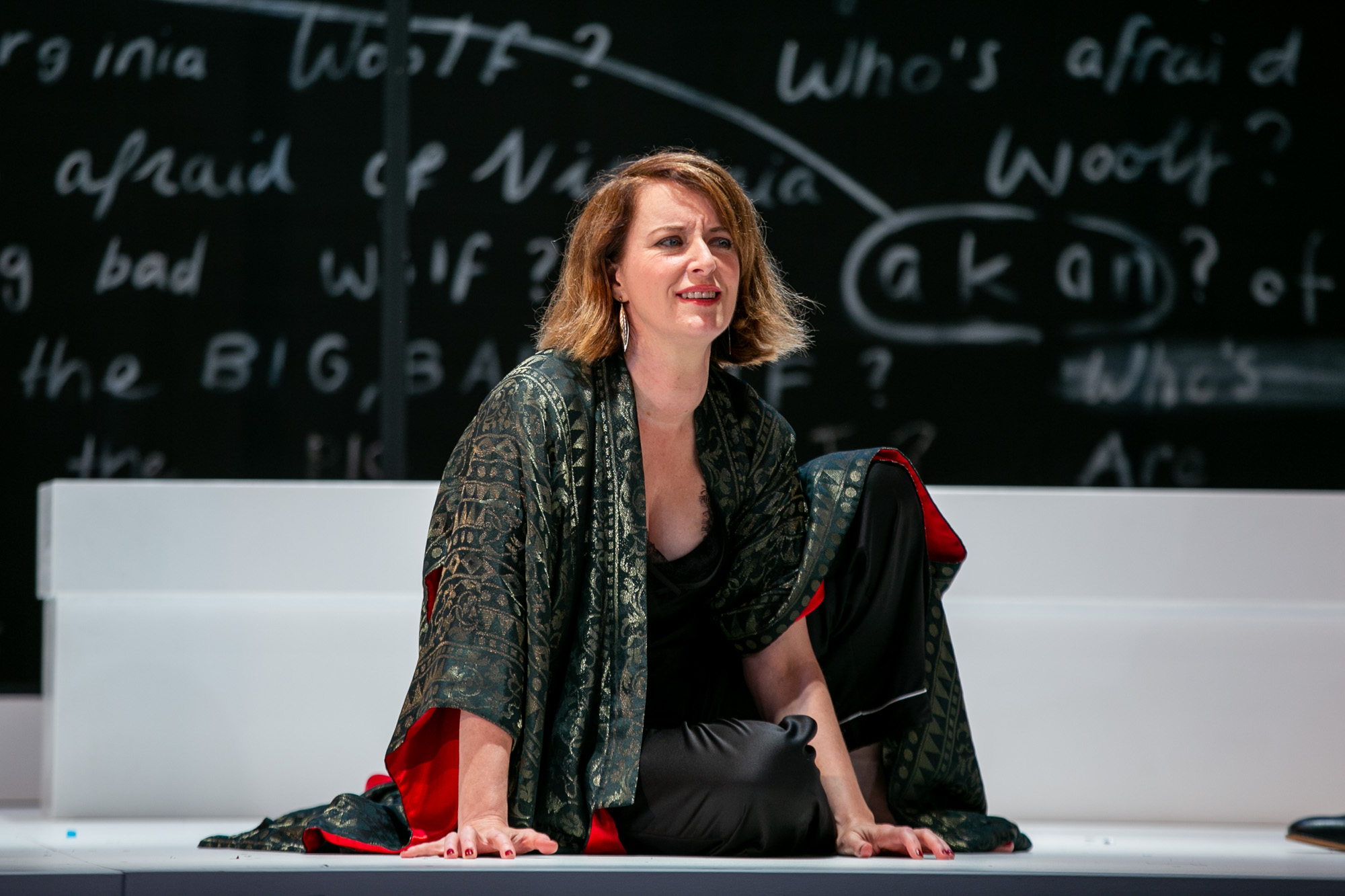

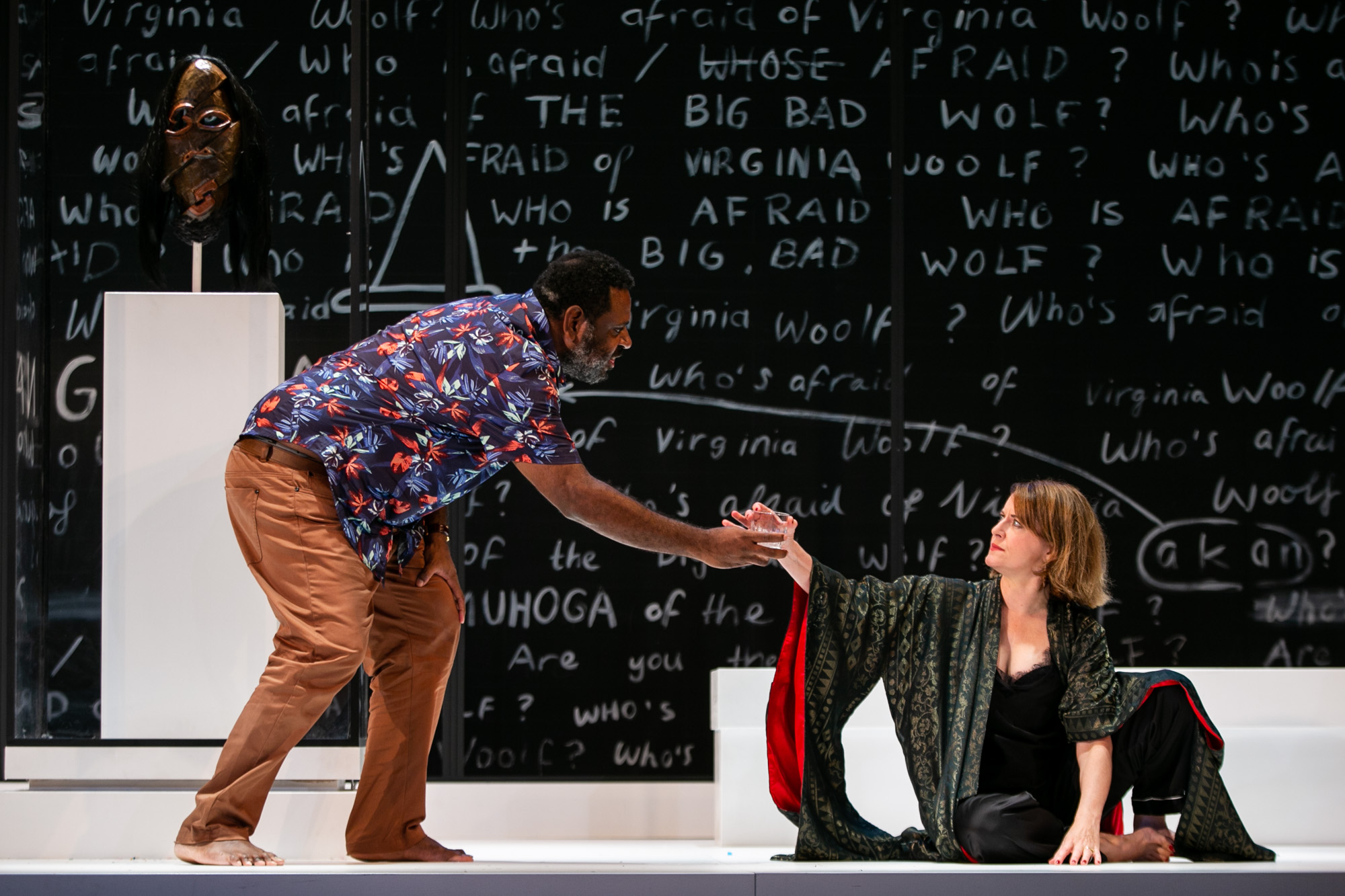

Director and choreographer Amy Campbell’s ambitious revival, is a breath-taking experience. Even though the lacklustre book remains tedious, it is always an unequivocal joy when the performers are in motion. Campbell’s love for the art of performance, and for those who do it, is palpable. Her show is faithful to the look and feel of 1970s New York, complete with slinky modern jazz flourishes that transport us back to a time of decadent glamour. Each second of dance is complex, detailed and powerful, a real sumptuous feast for the eyes.

Peter Rubie’s lights are at least as visually impressive. They enhance perfectly every scene that unfolds, sometimes quiet and subtle, sometimes flamboyantly bombastic, but always stylish and surprising. Whether accompanying bodies active or still, Rubie’s work is consistently imaginative, never settling for the obvious. The beauty he delivers is truly sublime. Christine Mutton’s costumes too, are noteworthy, in bringing both realism, and vibrant, balanced colour, to a staging that will be remembered for its unparalleled resplendence.

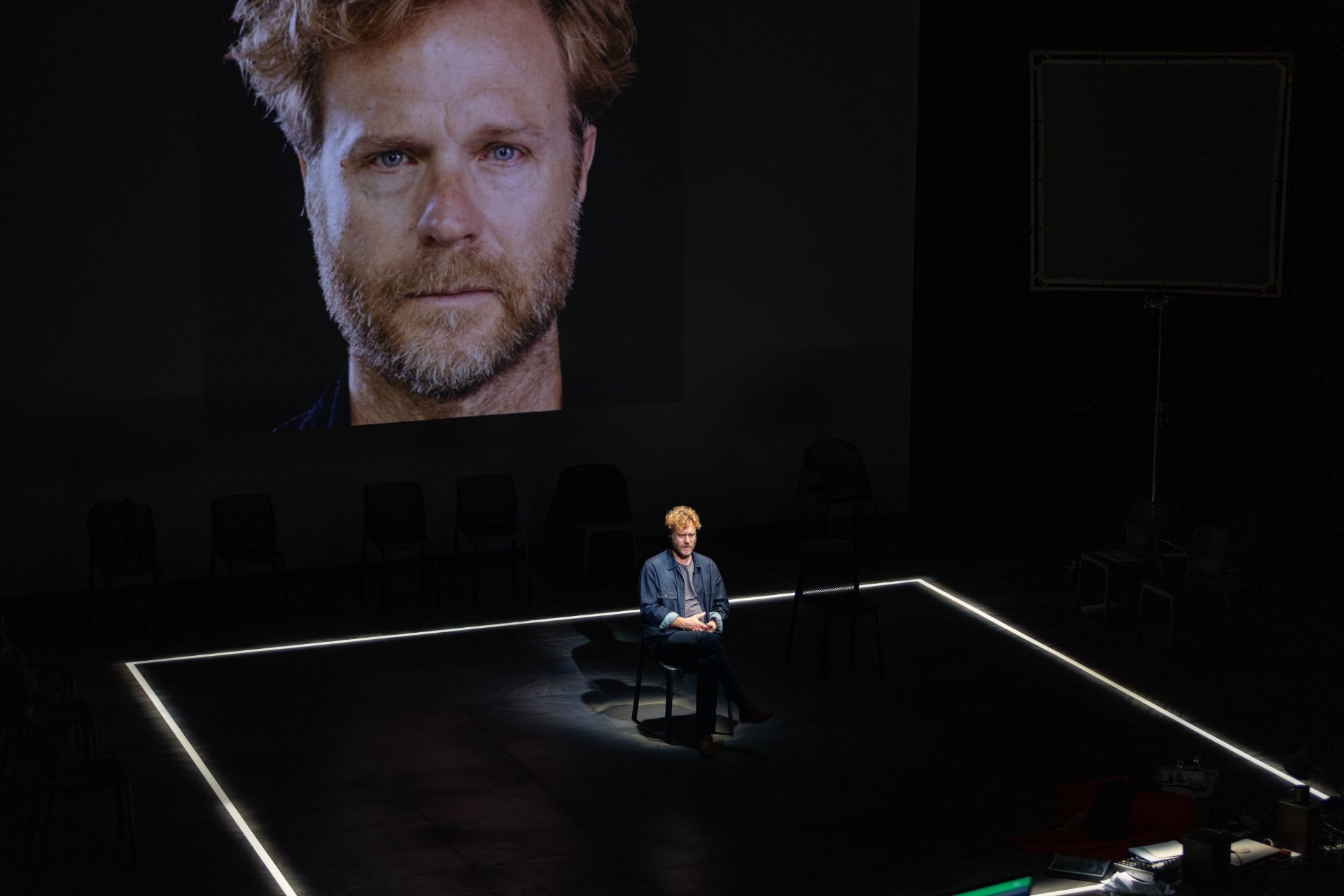

The pivotal role of Zach is played by Adam Jon Fiorentino, whose use of voice marvellously regulates atmosphere from start to finish. Angelique Cassimatis delivers the singularly most poignant anecdote, as Cassie, complete with jaw dropping intensity in her iconic number, “The Music and the Mirror”. We fall for all of the cast, as they are foregrounded one at a time, but it is their work as a cohesive whole, that has us spellbound. Together, they are formidable.

Much has changed over these five decades, since the inception of A Chorus Line. For one, we are no longer tolerant of authority figures like Zach irresponsibly demanding their subordinates, to reveal secrets or to relive trauma, in the company of strangers. Women and men, in the arts especially, have started to reject the delineations between gender constructs, and in the process are learning to meld the false differences of us and them. The theatrical arts however, remain a pure vehicle for communities to congregate, to debate, and to share. Since time immemorial, we have formulated ways to listen to each other, to understand our neighbours, and to reach consensus, hard as it might be, because we always knew that on our own, we are doomed to fail. There are no queens and kings in A Chorus Line, only a united front that can weather anything, and keep the dreams alive.