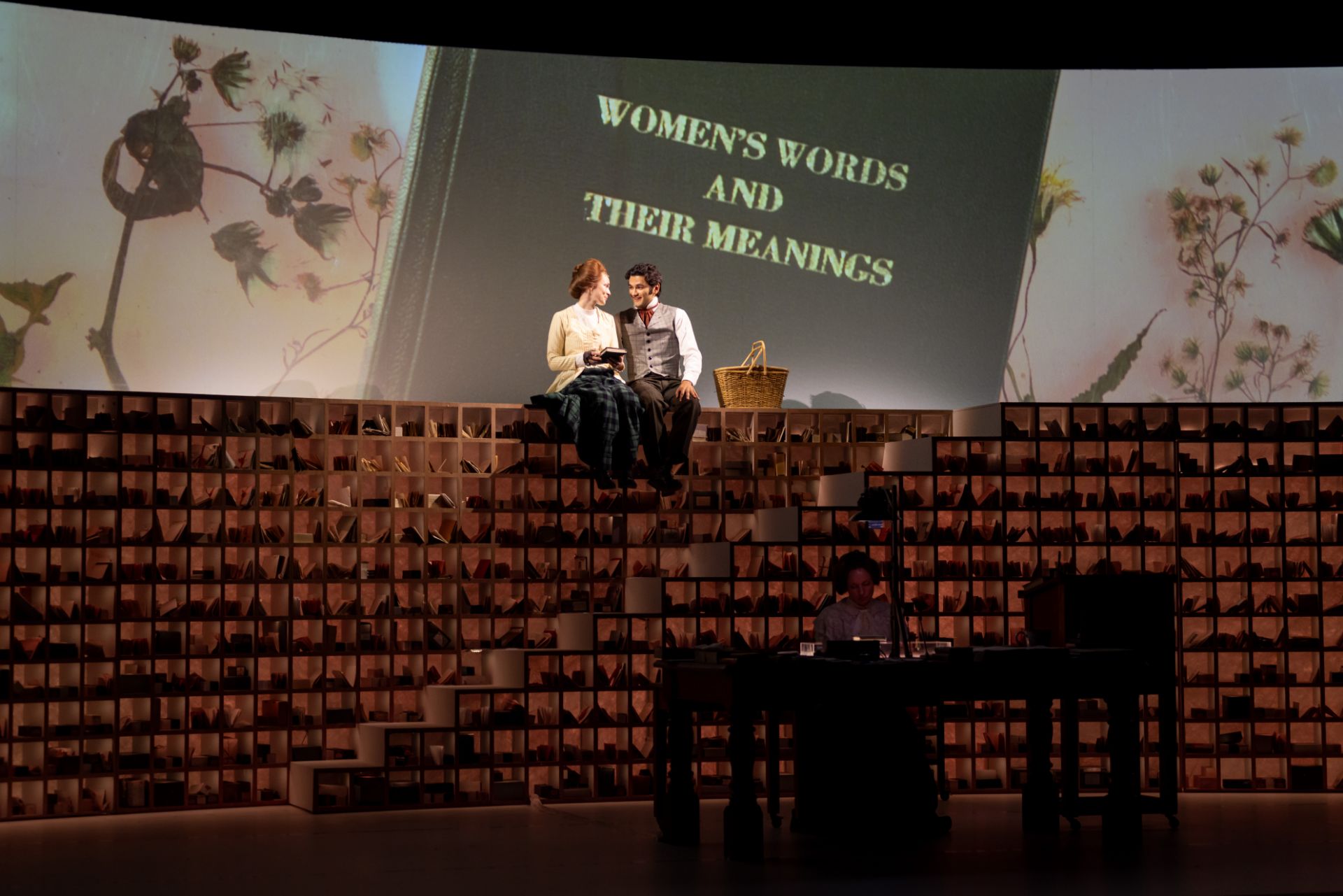

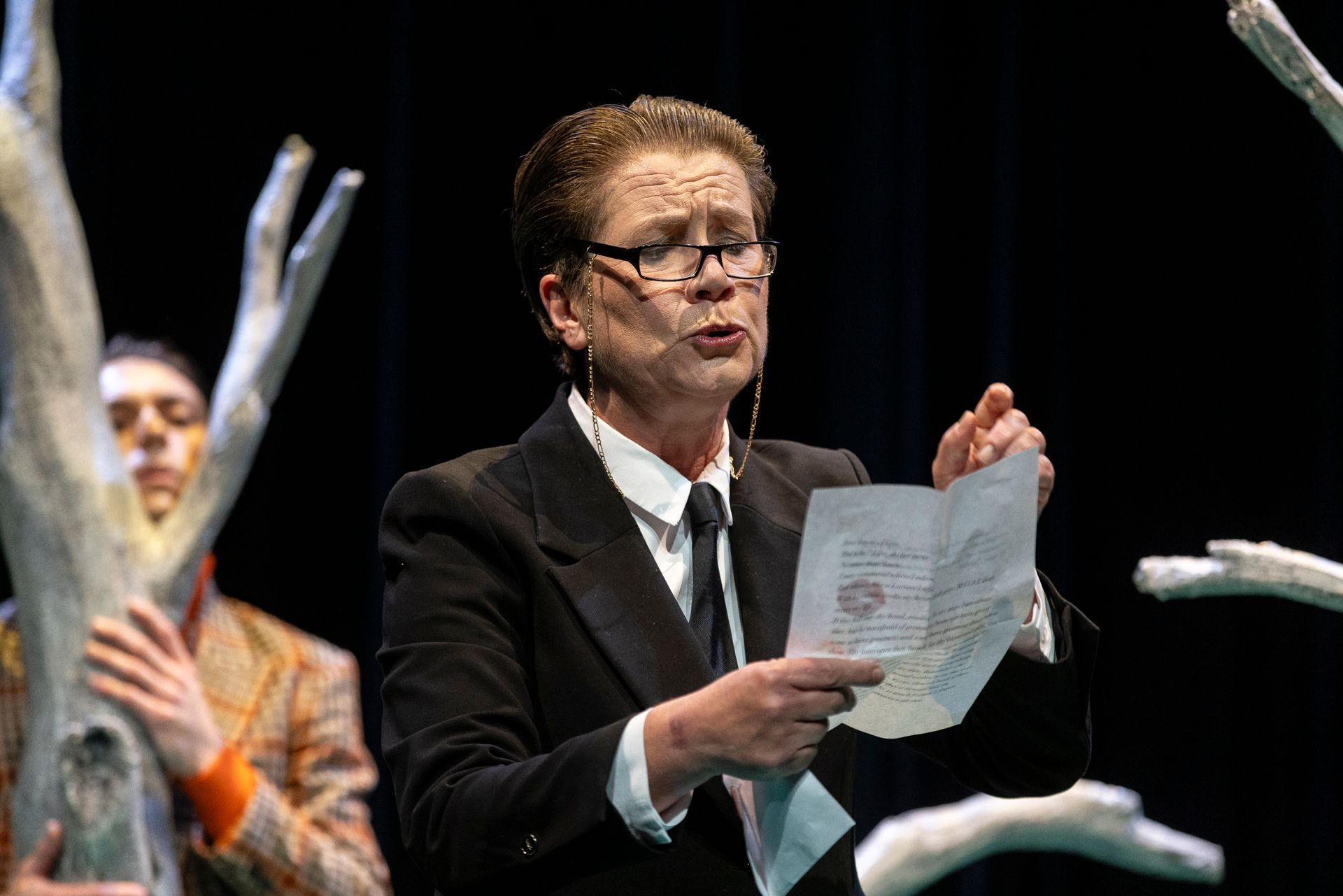

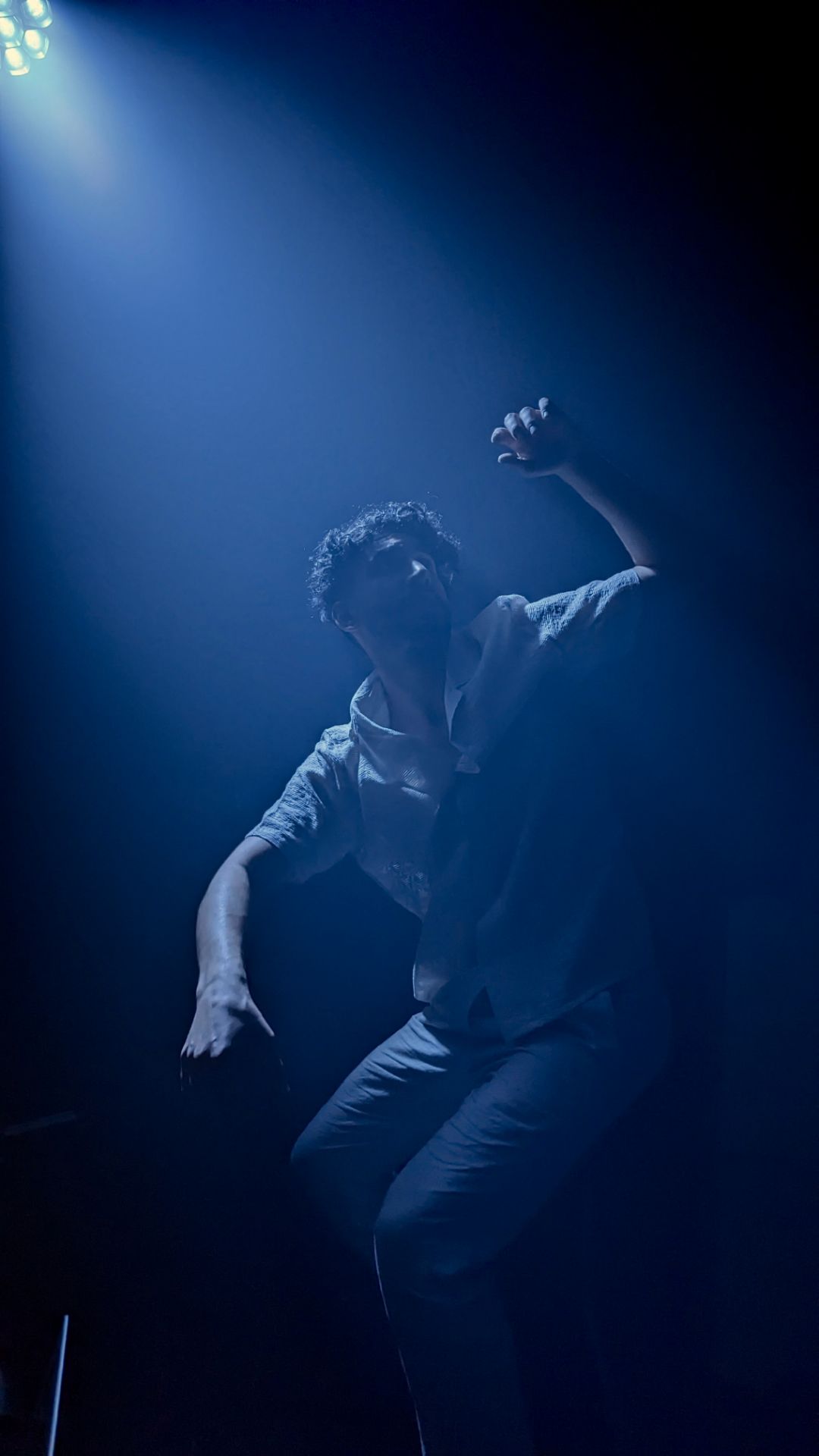

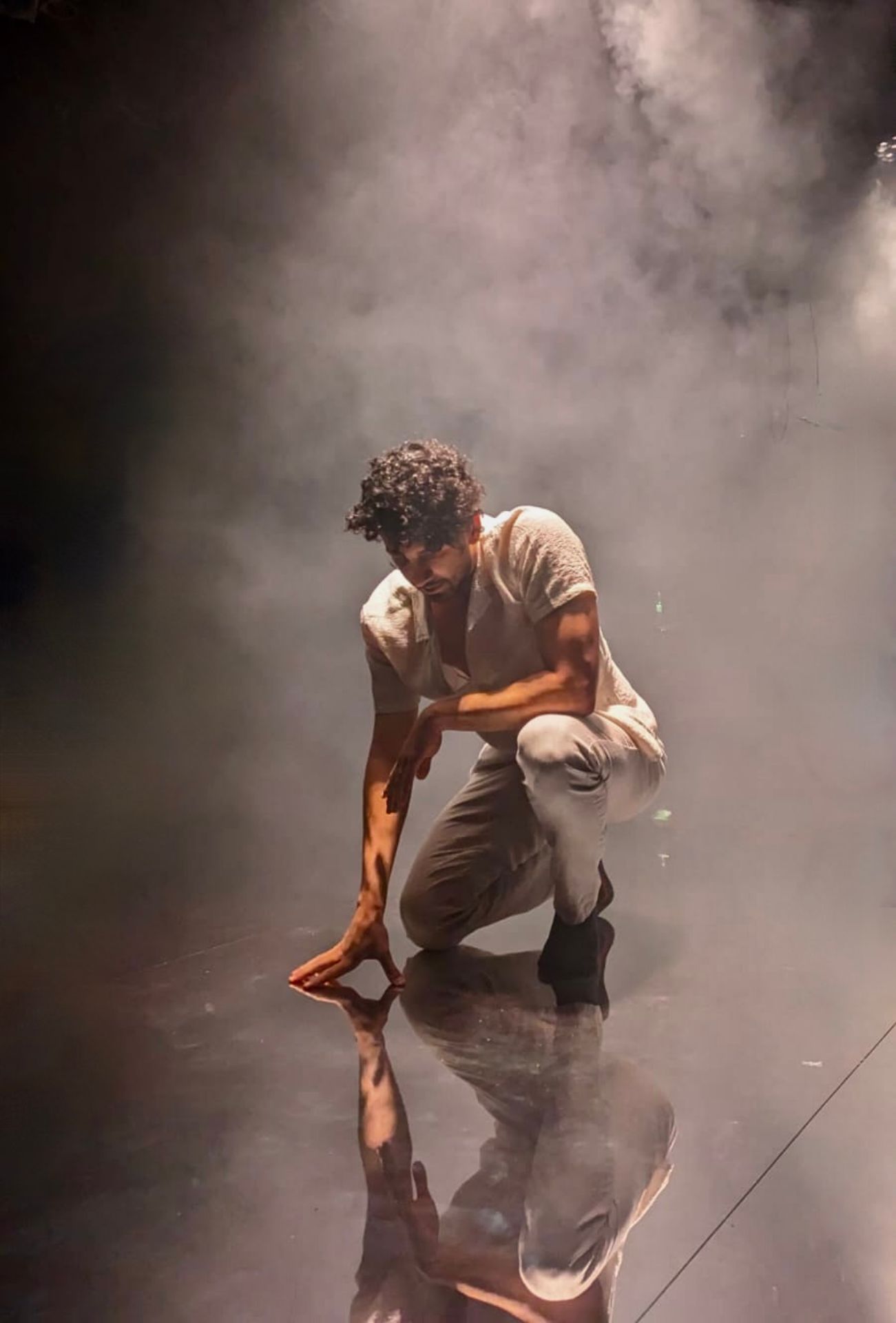

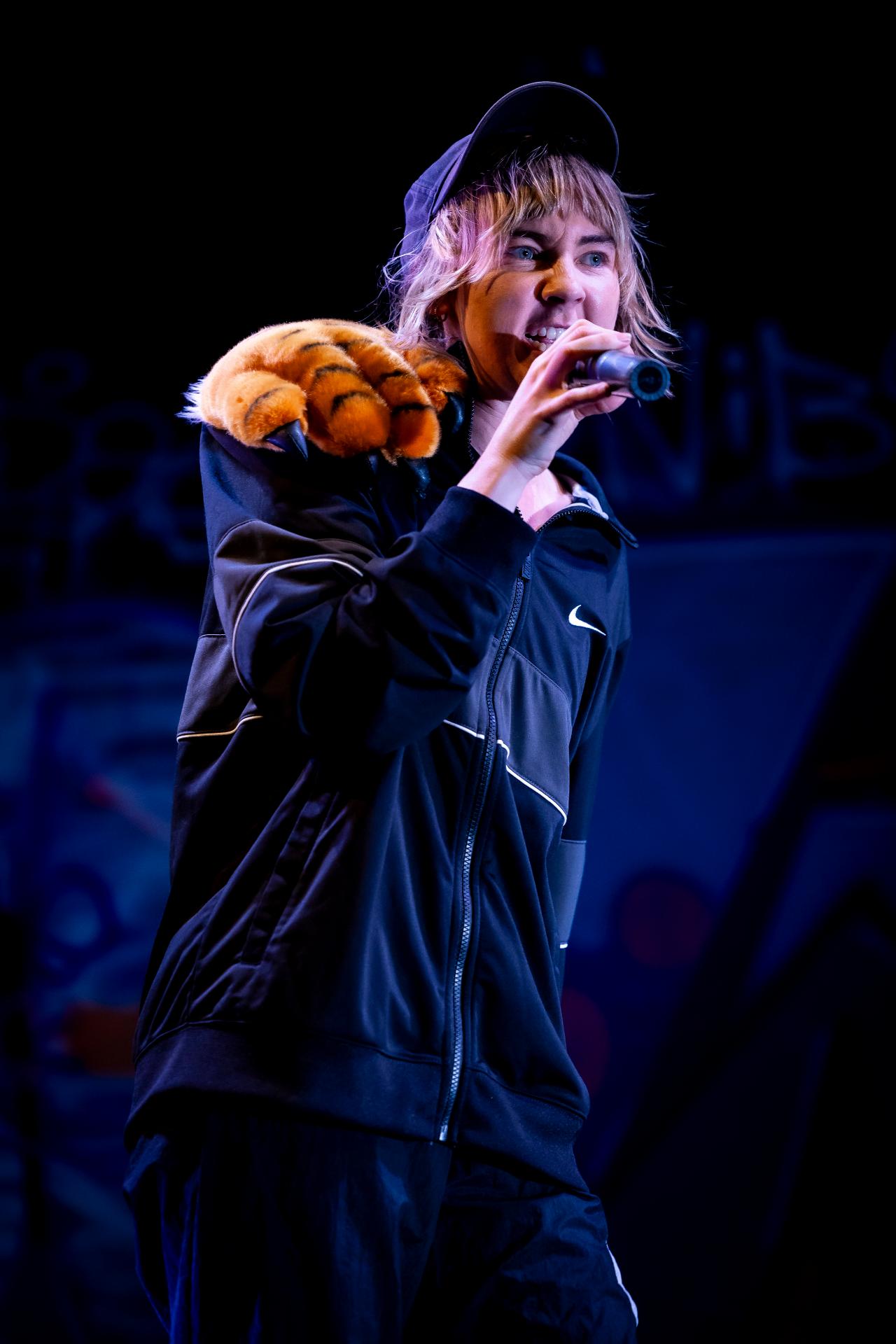

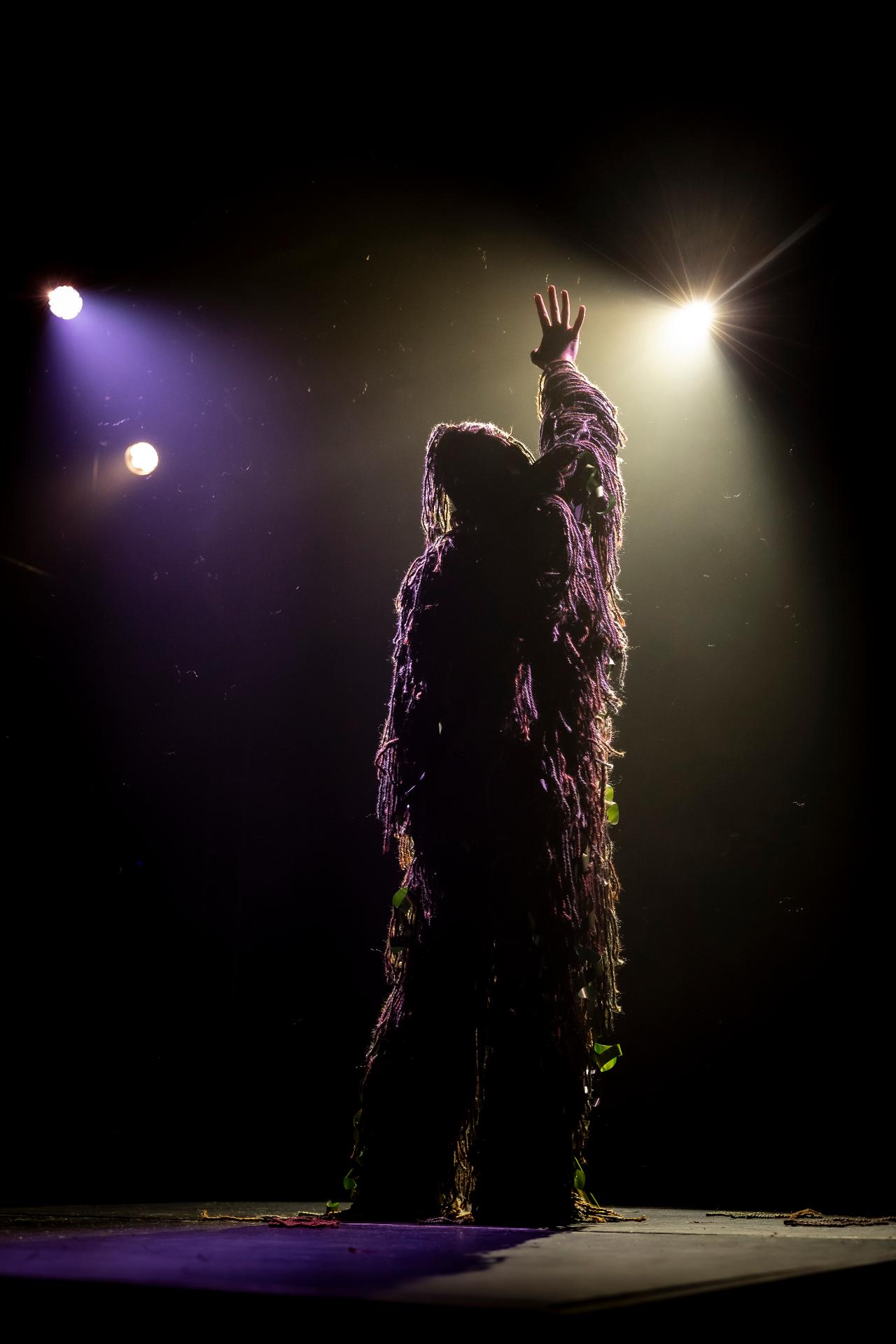

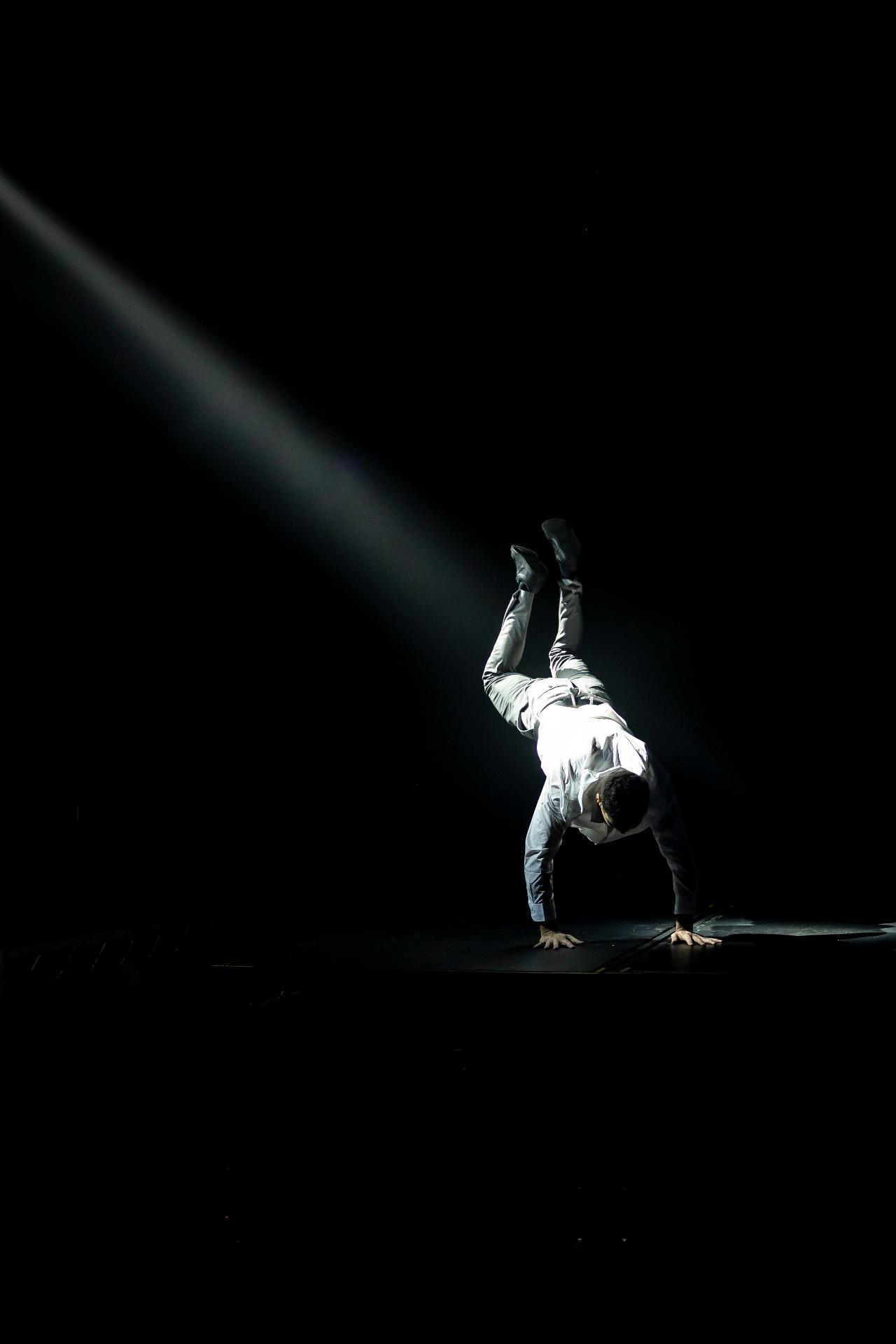

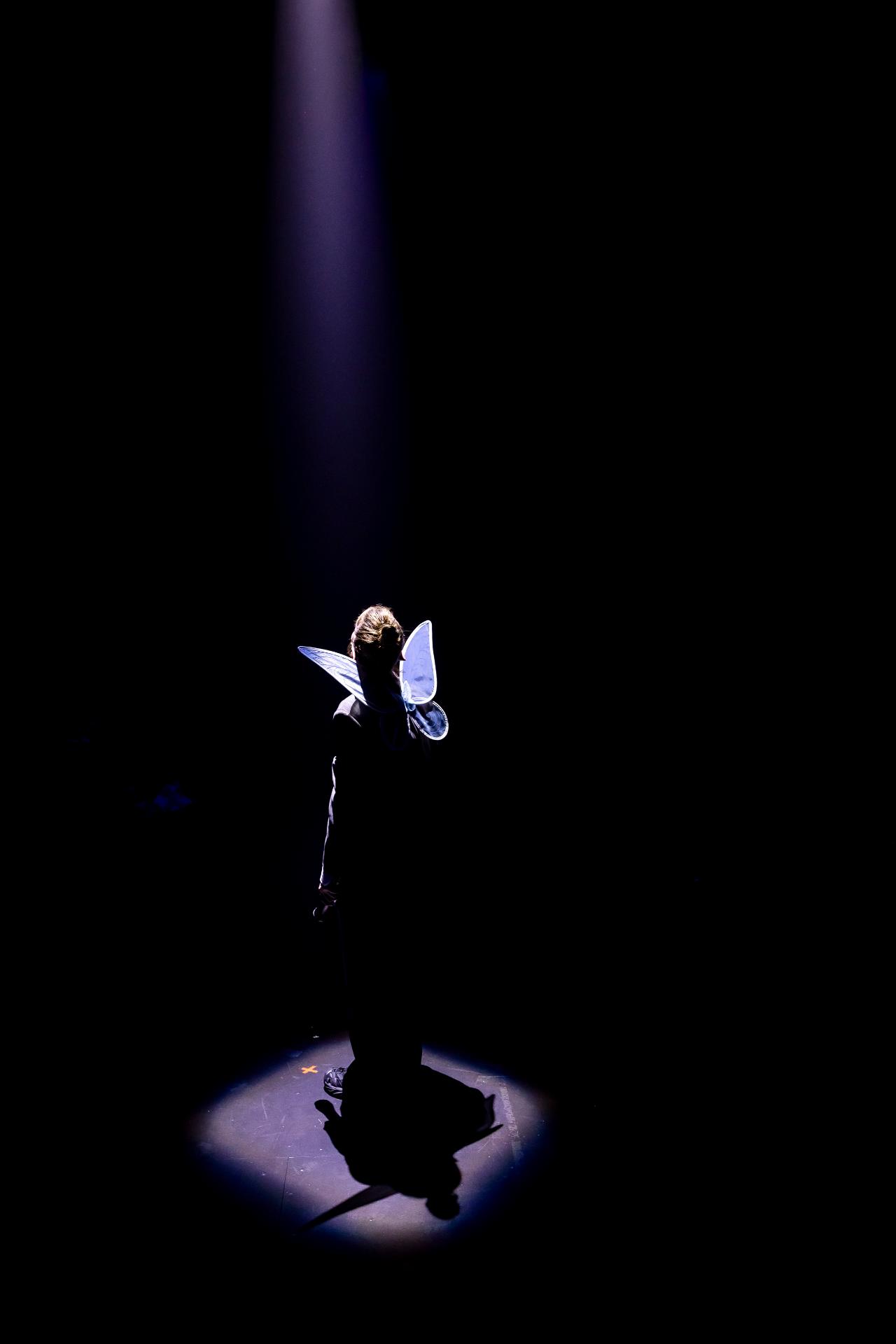

Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Nov 10 – Dec 1, 2023

Directors: Craig Baldwin, Eliza Scott

Cast: Samuel Beazley, Adriane Daff, Emma Harrison, Romain Hassanin, Julia Robertson, Eliza Scott, Anusha Thomas

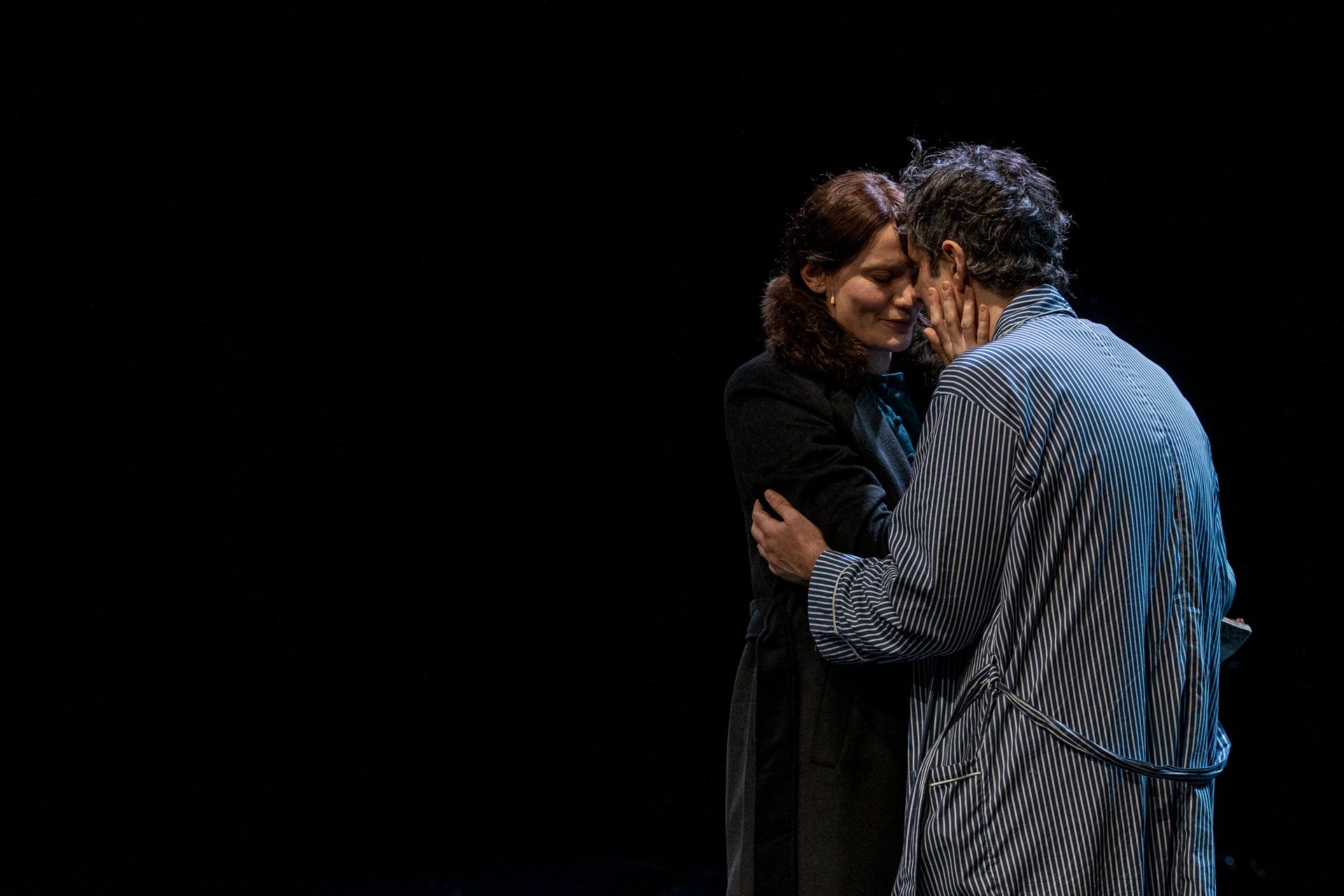

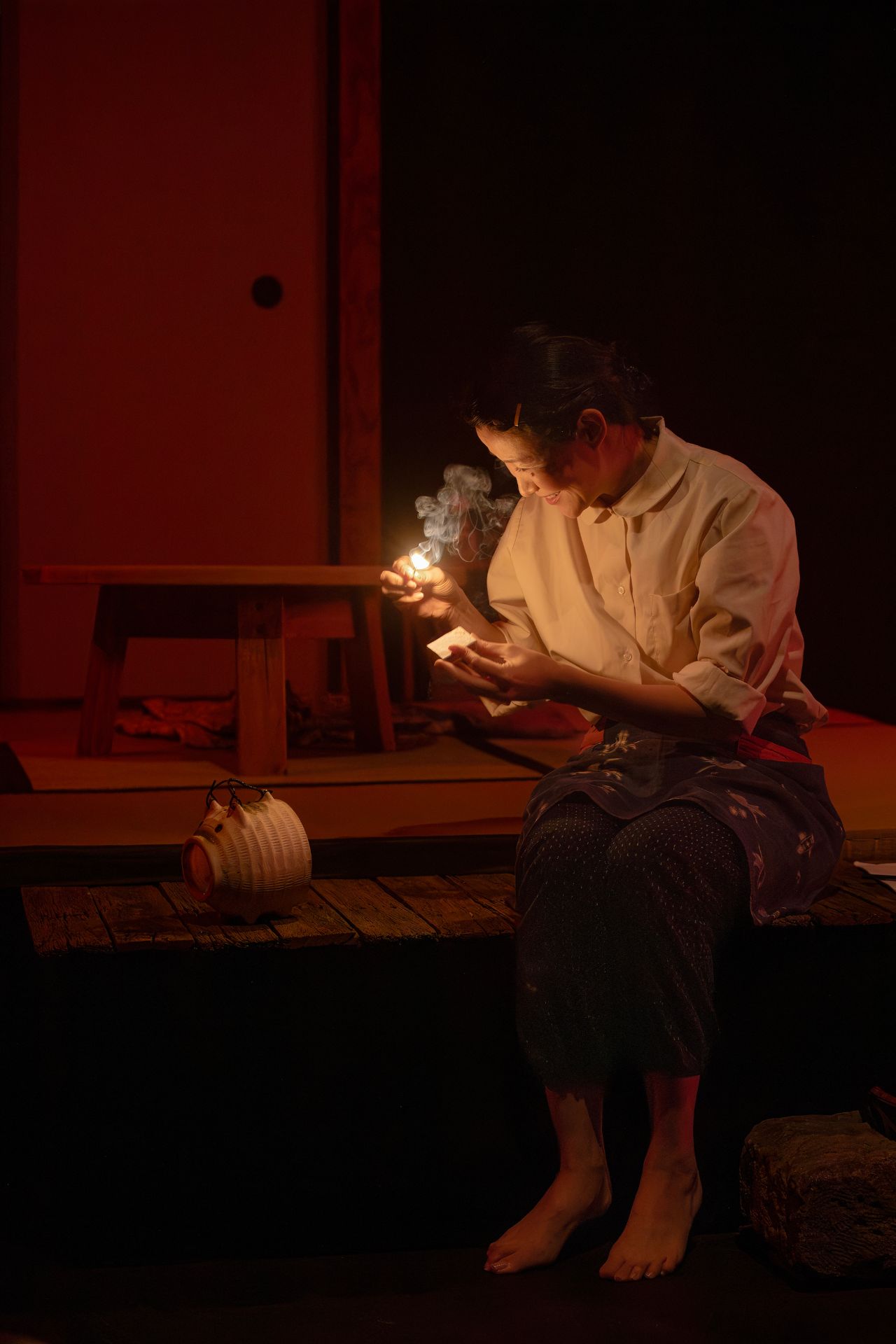

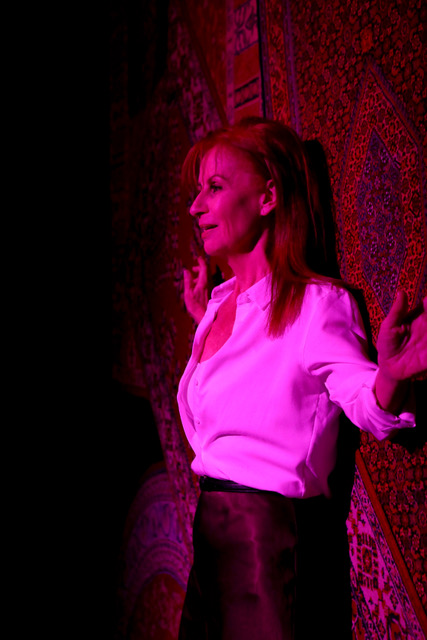

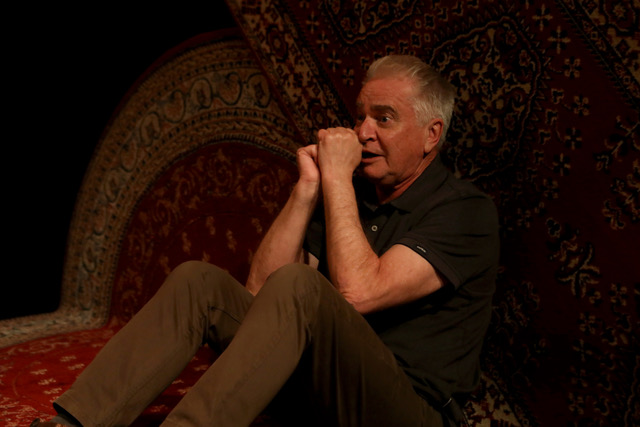

Images by Grant Leslie

Theatre review

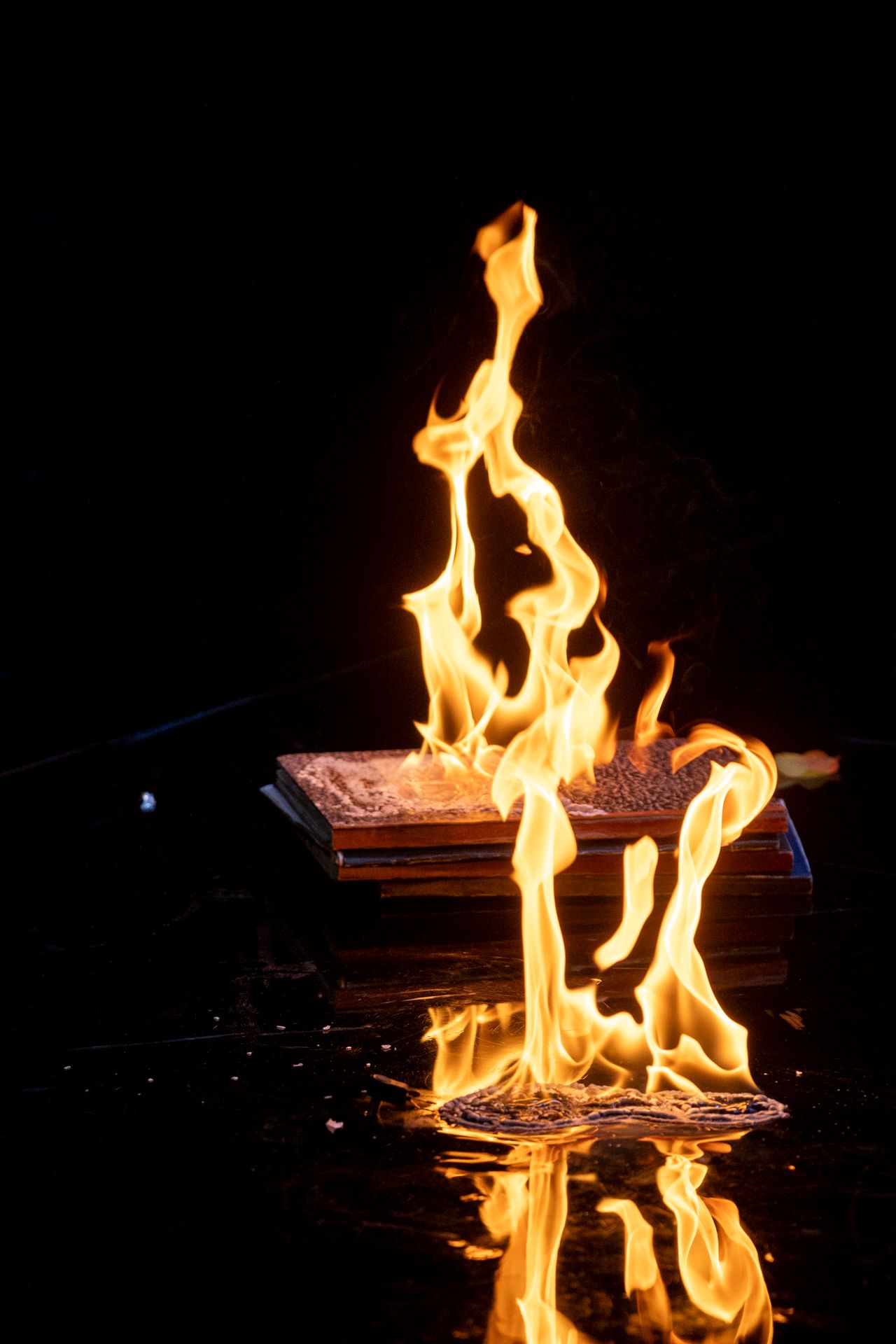

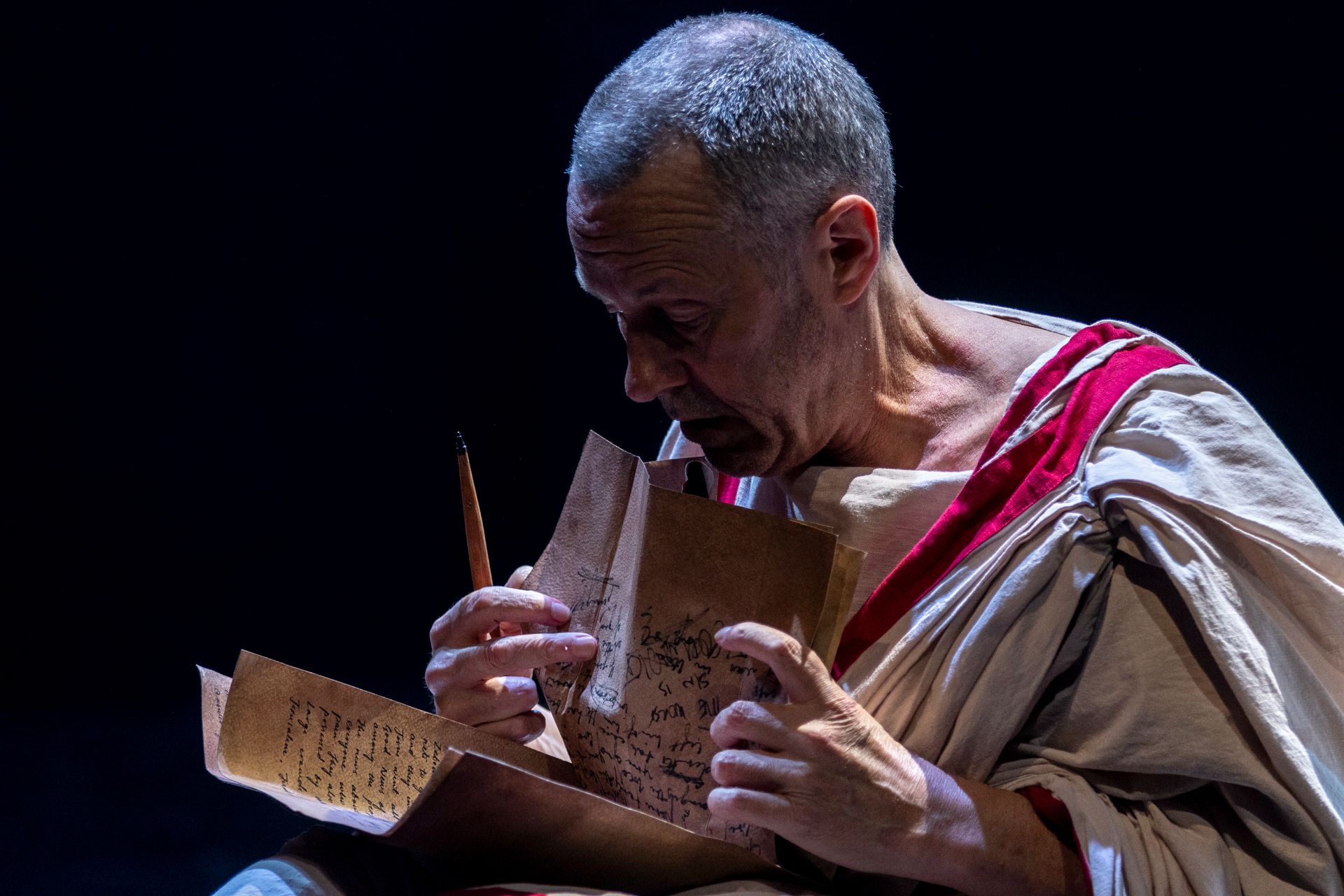

Based on the 1911 novel Peter and Wendy by J.M. Barrie, The Lost Boys is a freeform immersive work of theatre, dealing with issues pertaining to early masculinity and the loss of innocence. Its scene are distinct and separate, each with an independent style of presentation, but kept within a uniform aesthetic by directors Craig Baldwin and Eliza Scott, to convey a sense of cohesion for the production.

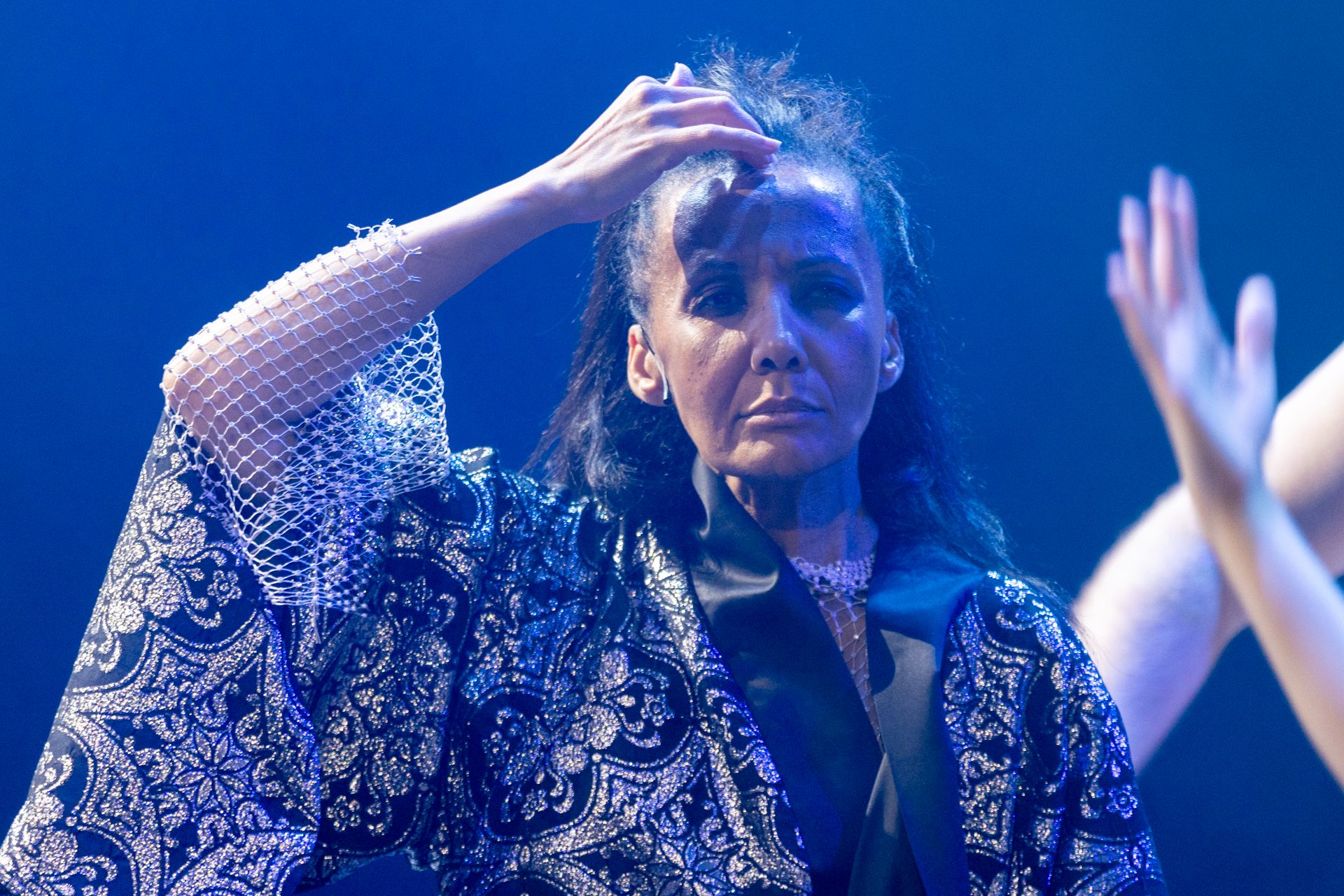

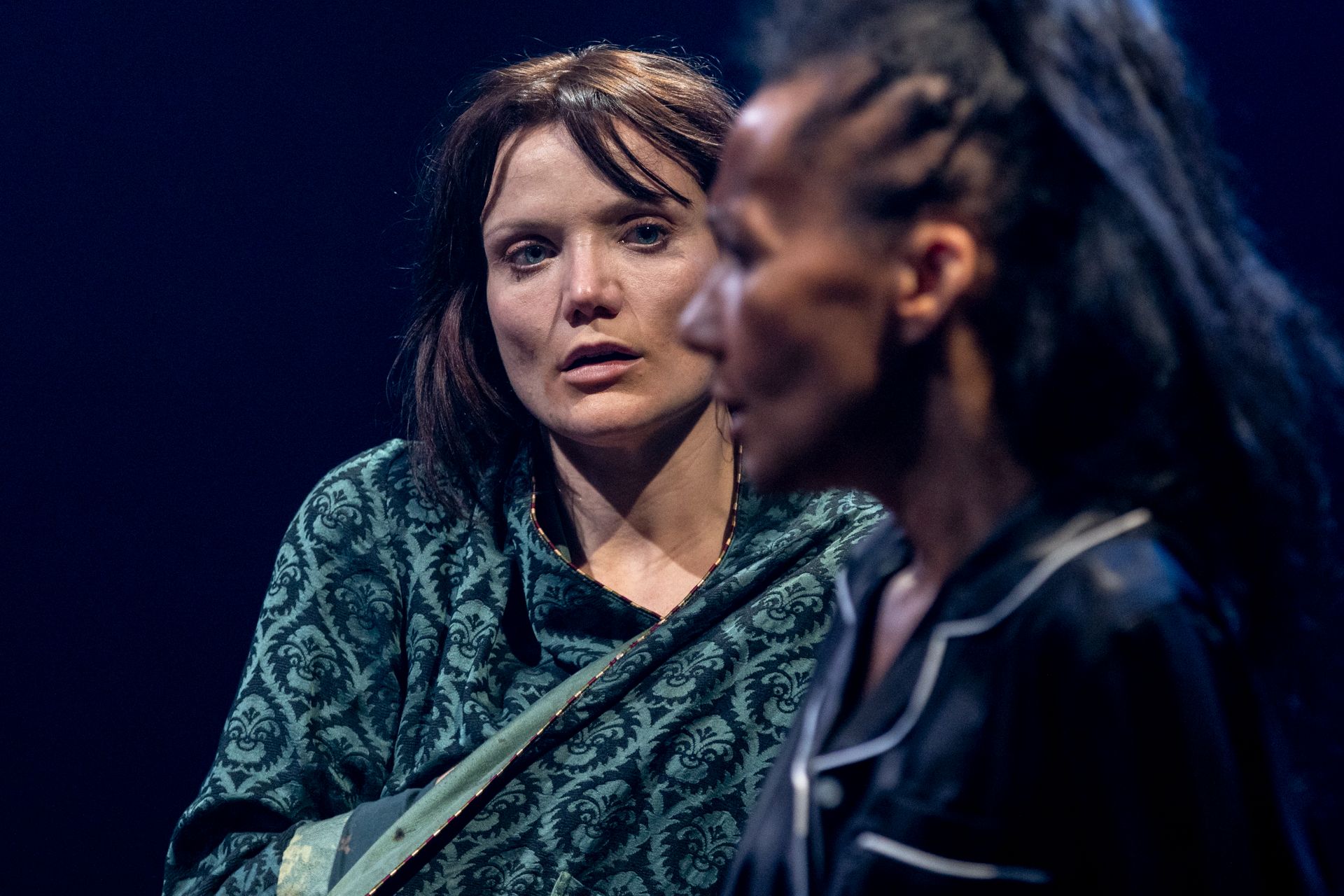

Set and lighting design by Ryan McDonald addresses tastefully the unusual spatial concerns of The Lost Boys, able to deliver style and a quality of surprise, for the series of imagery we encounter. Costumes by Esther Zhong are appropriately youthful, accurate in depicting the times and the culture being interrogated. Sounds are a highlight, especially the electronic music being deployed whether pulsating or ambient, to have us engaged with the show’s carefully calibrated atmospherics.

An ensemble of eight with divergent skills and talents, creates a one-hour presentation notable for its poetic sensibility. The Lost Boys commences at high octane, full of energy and promise, but struggles to sustain that intensity. Its first half is enjoyable for quirky and startling interpretations of Barrie’s writing, but an unintended juvenility sets in midway, and the show turns regretfully banal. There is no questioning the commitment on display by the vibrant collective, but it seems their ingenuity is depleted too early in the piece.

It is crucial that we undertake a deconstruction of masculinity, and redefine its virtues, for men and for people of other genders. Much of masculinity has been harmful, but like all other damaging systems that furnish power to few, it is stridently persistent, bolstered perversely by those who suffer its consequences. Its values are so ubiquitous that we rarely question their validity, unconsciously absorbing them into the ways we navigate all of existence. We regard them as natural and elemental, when they are demonstrably malleable, with meanings that are almost entirely imaginary and indeed, illusory. We may not be able to do away with gender altogether in the current lifetime, but disallowing it from taking on immutable and invulnerable shapes, is ultimately of benefit to all.