Venue: Carriageworks (Eveleigh NSW), Oct 19-22, 2023

Director: Tessa Leong

Lead Artist & Performer: Rainbow Chan 陳雋然

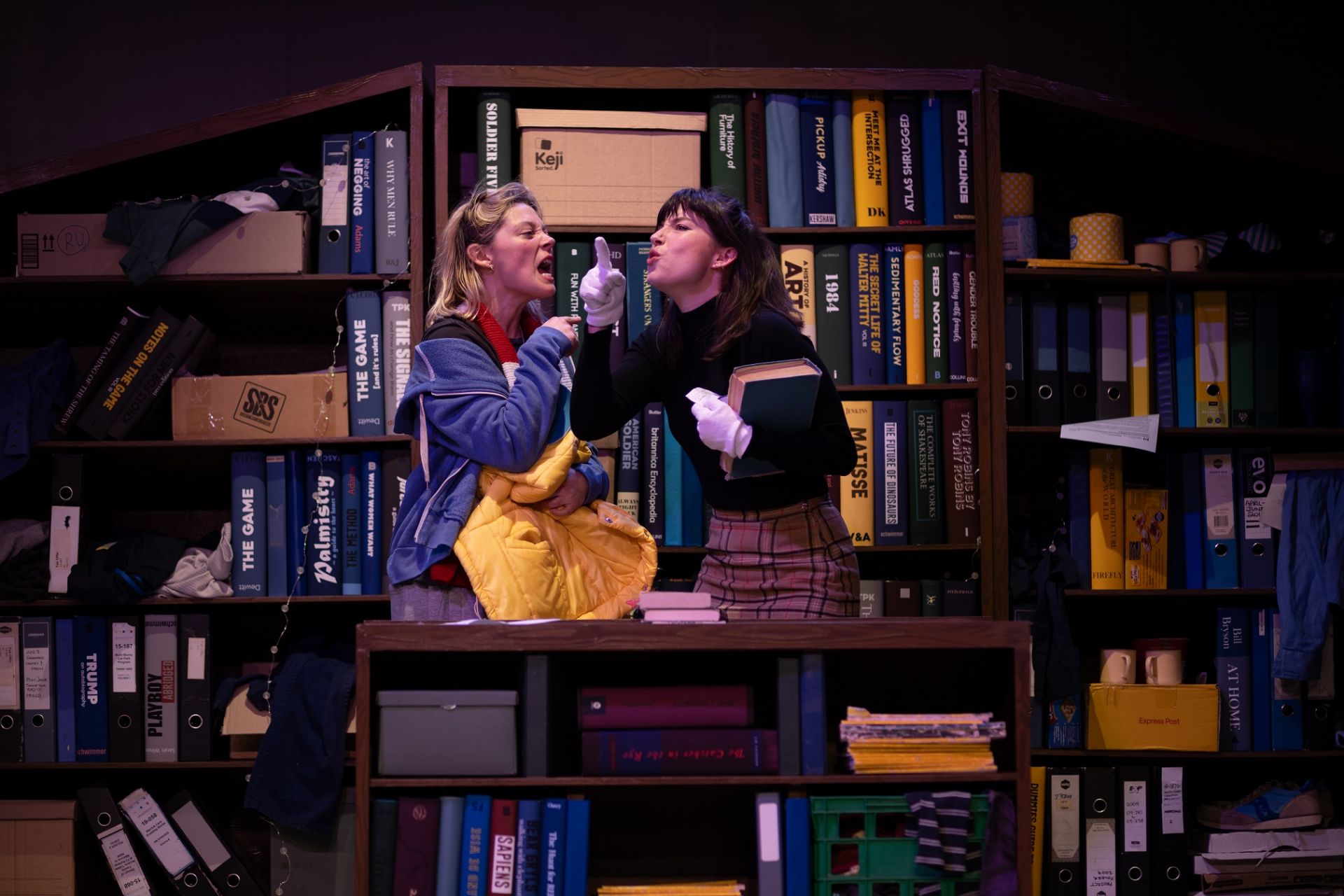

Images by Joseph Mayers

Theatre review

Arriving as a child from Hong Kong in 1996, a year before the handover to China, Rainbow Chan 陳雋然 grew up like many Australians, between cultures. Now that we are in a moment that feels as though assimilation to whiteness is decisively a thing of the past (at least for now), immigrants like Chan are scrambling to fully reclaim their roots, for a state of identification more meaningful than before. It is not an abandonment of Australianness, but an evolution in the narrative of our survival, when we attempt to foster a greater connection with that which had to be left behind.

Through conversations and consultations with her mother Irene Cheung 張翠屏, which form the basis of The Bridal Lament 哭嫁歌, Chan reaches back to marital customs of her people to form an intricate study of traditions, many of which are obsolete, and in the process attains a new understanding of where she had come from. A key feature are the songs young women learn from their mothers in the Weitou dialect, that they sing for 3 days before crossing the threshold to become wives. Chan’s show is an archive of sorts, including some of those hitherto forgotten tunes, alongside her own compositions, for a theatrical presentation that offers a bridge that examines a particular collective history, preoccupied with a past yet feels so much to be about our future.

Chan’s music draws heavily from pop genres, but is unmistakeably poetic in nature. It stretches deeply in ways that ensure resonance, beyond cerebral concerns. Directed by Tessa Leong, The Bridal Lament 哭嫁歌 is tender yet intense, in its rendering of a contemporary Chinese-Australian perspective and attitude. As performer, Chan is captivating in this solo work, although portions of the staging can feel sparse, in need of more imaginative support of one woman and her immensely vast story.

Set and costumes by Al Joel and Emily Borghi are sophisticated, especially memorable for a highly ostentatious beaded archway evoking concepts of travel and searching, and that also allows for some truly magical theatricality, when combined with extraordinarily dynamic lights as conceived by Govin Ruben. Video projections by Rel Pham are another crucial element, as vehicle to relay fascinating minutiae from Chan’s research, and to inspire emotional responses, for these meditations that can never be divorced from longing and heartache.

When we cut our apron strings, is ironically when we become ready to draw from our mothers’ wealth of knowledge and experience. Being a woman is hard in this world, and guidance from mothers (biological or otherwise) is unequivocally invaluable. It is imperative that we honour women who have grown and aged, to fight against a hegemony that wishes to diminish them and render them invisible. We must understand that forces responsible for so many of our world’s deficiencies are the same ones that tell us not to believe women. Mothers may not always make things easy, but they often do know best.