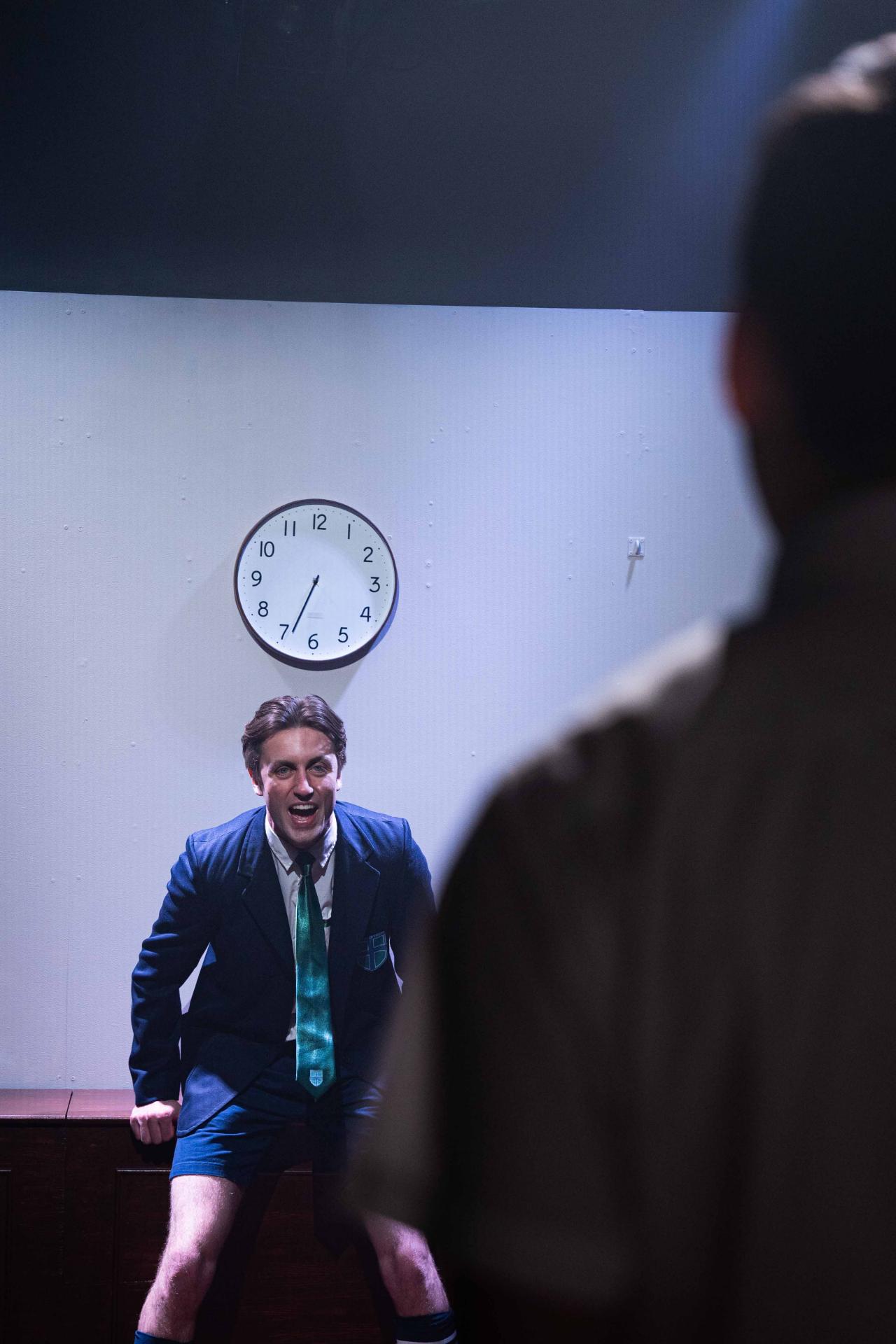

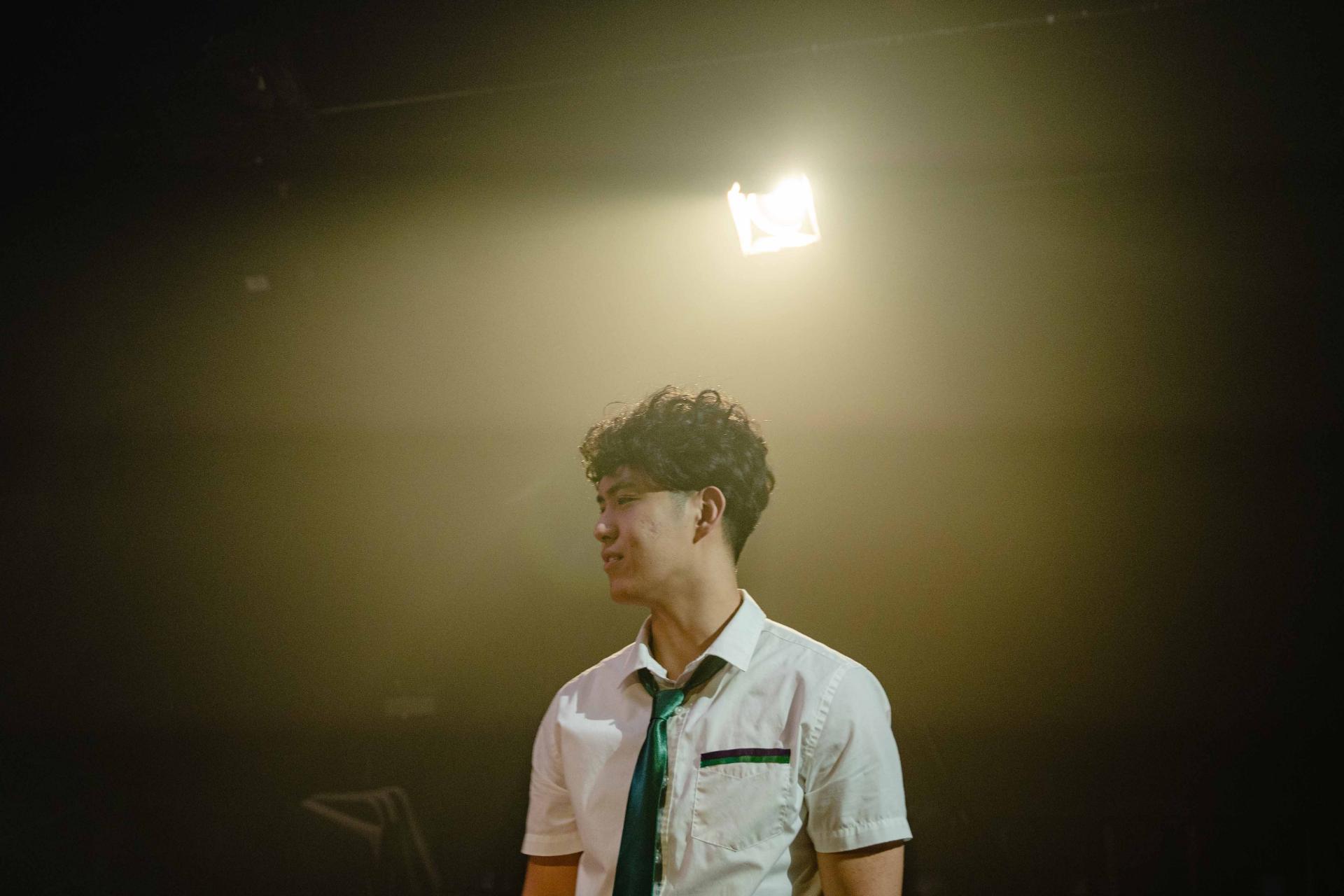

Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Sep 28 – Nov 3, 2024

Music & Lyrics: Carmel Dean

Additional lyrics: Miriam Laube

Director: Blazey Best

Cast: Stefanie Caccamo, Sarah Murr, Zahra Newman, Elenoa Rokobaro

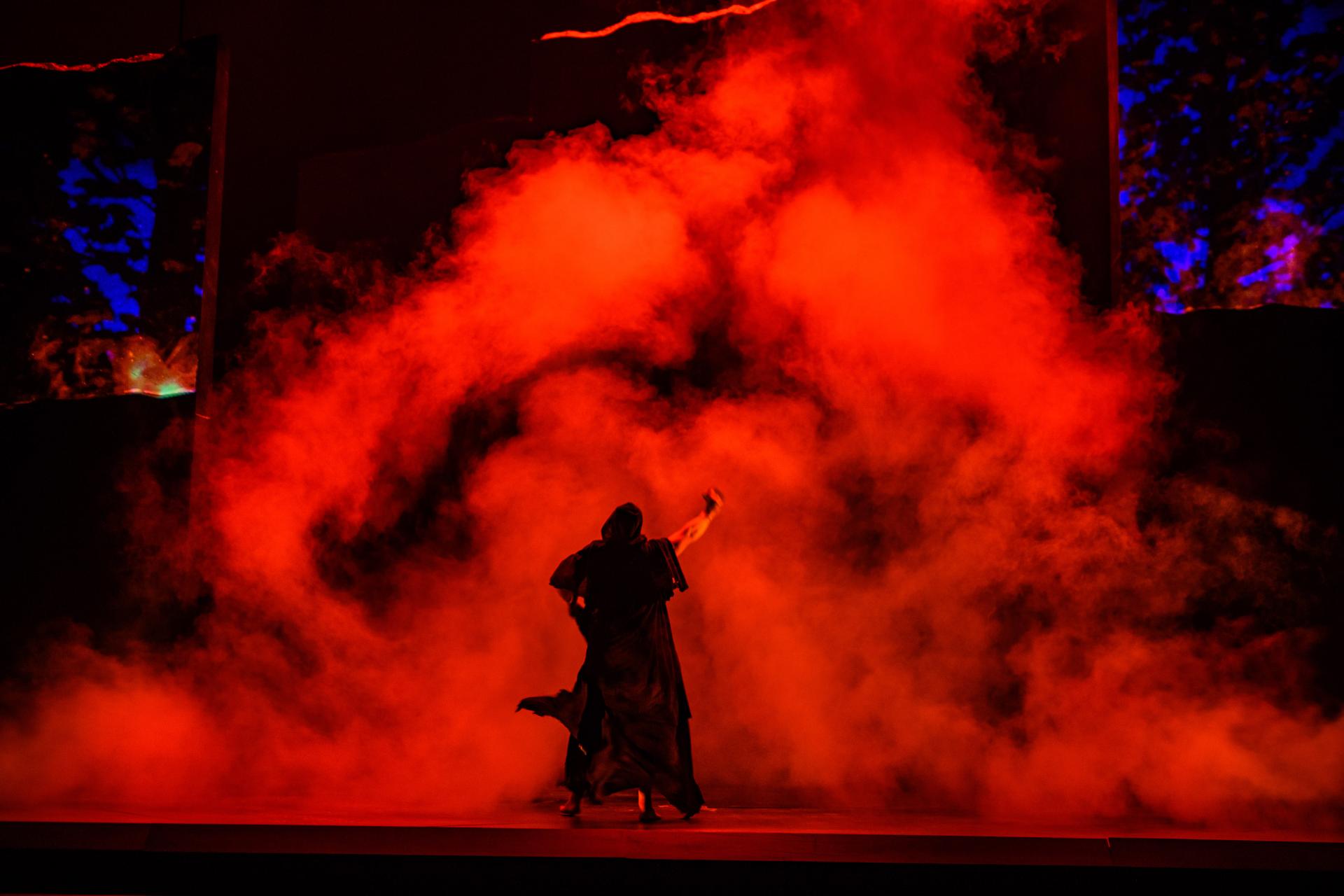

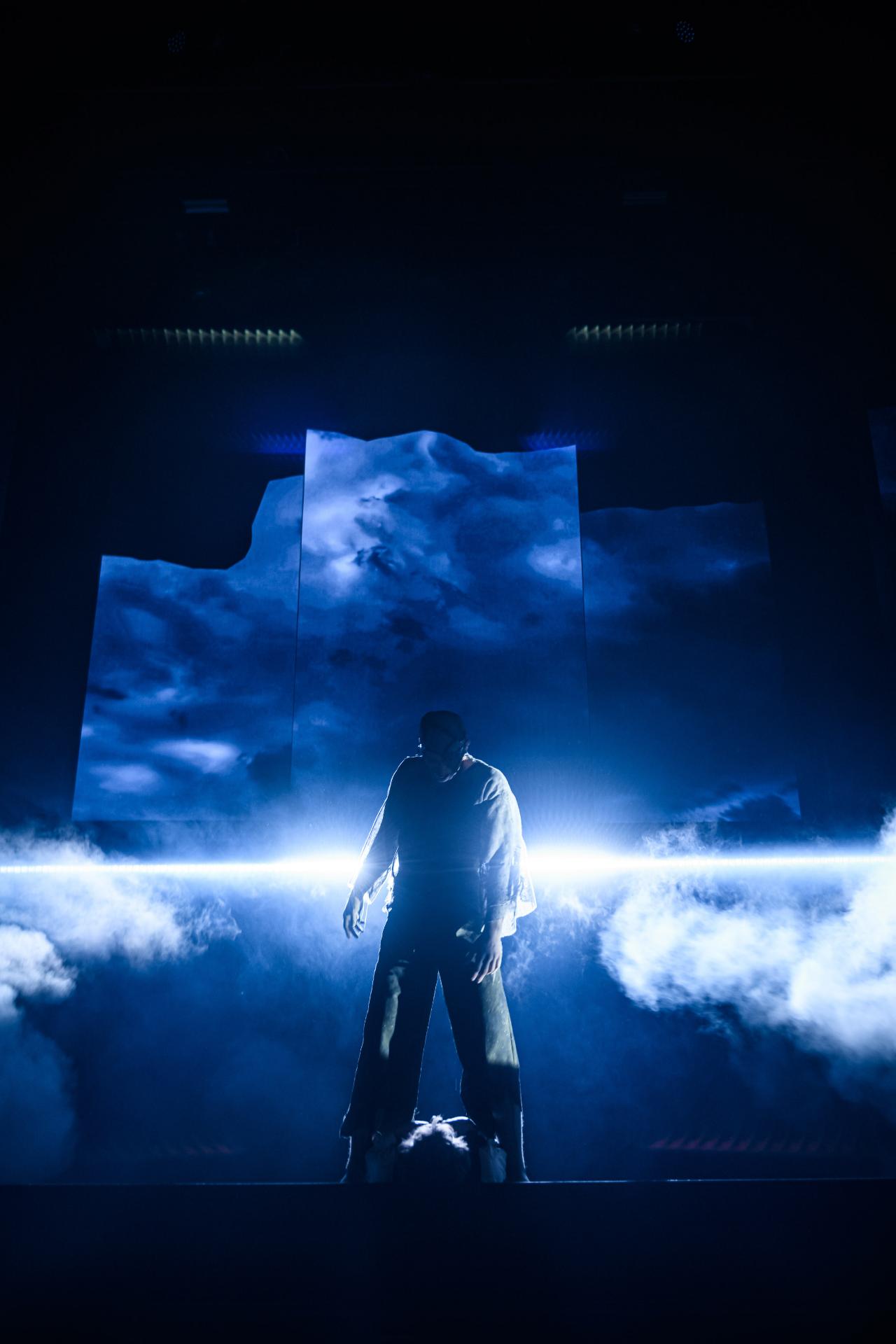

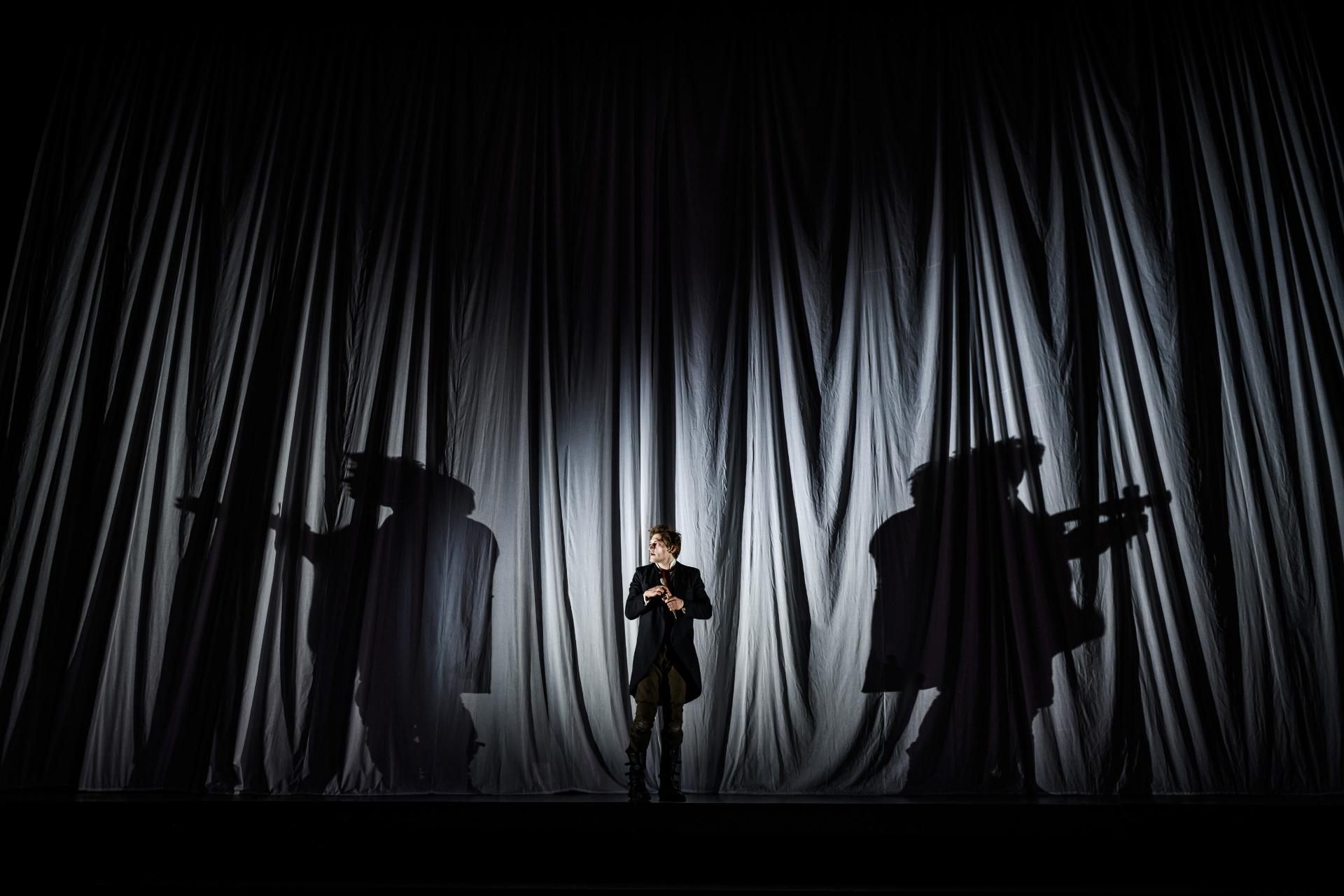

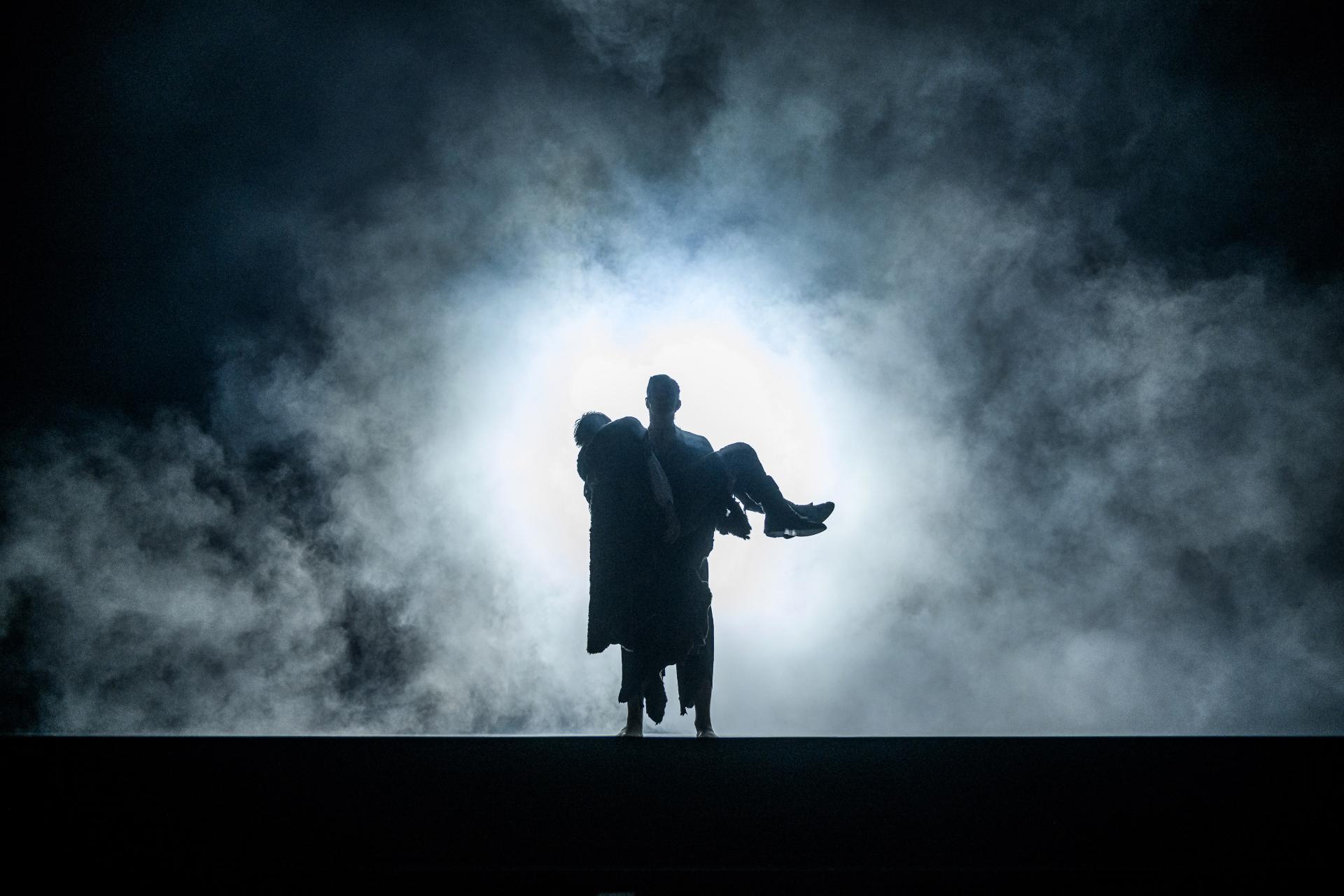

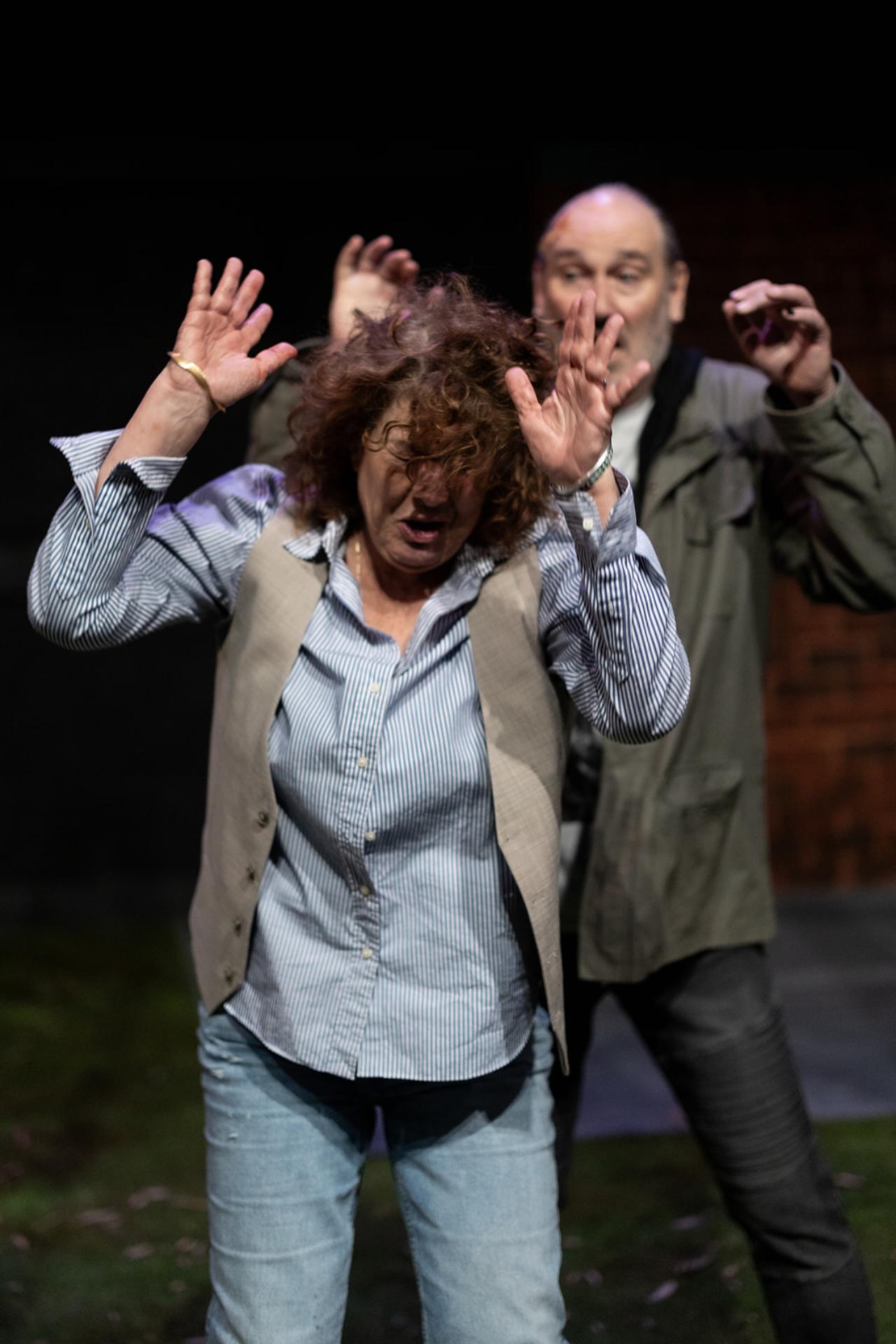

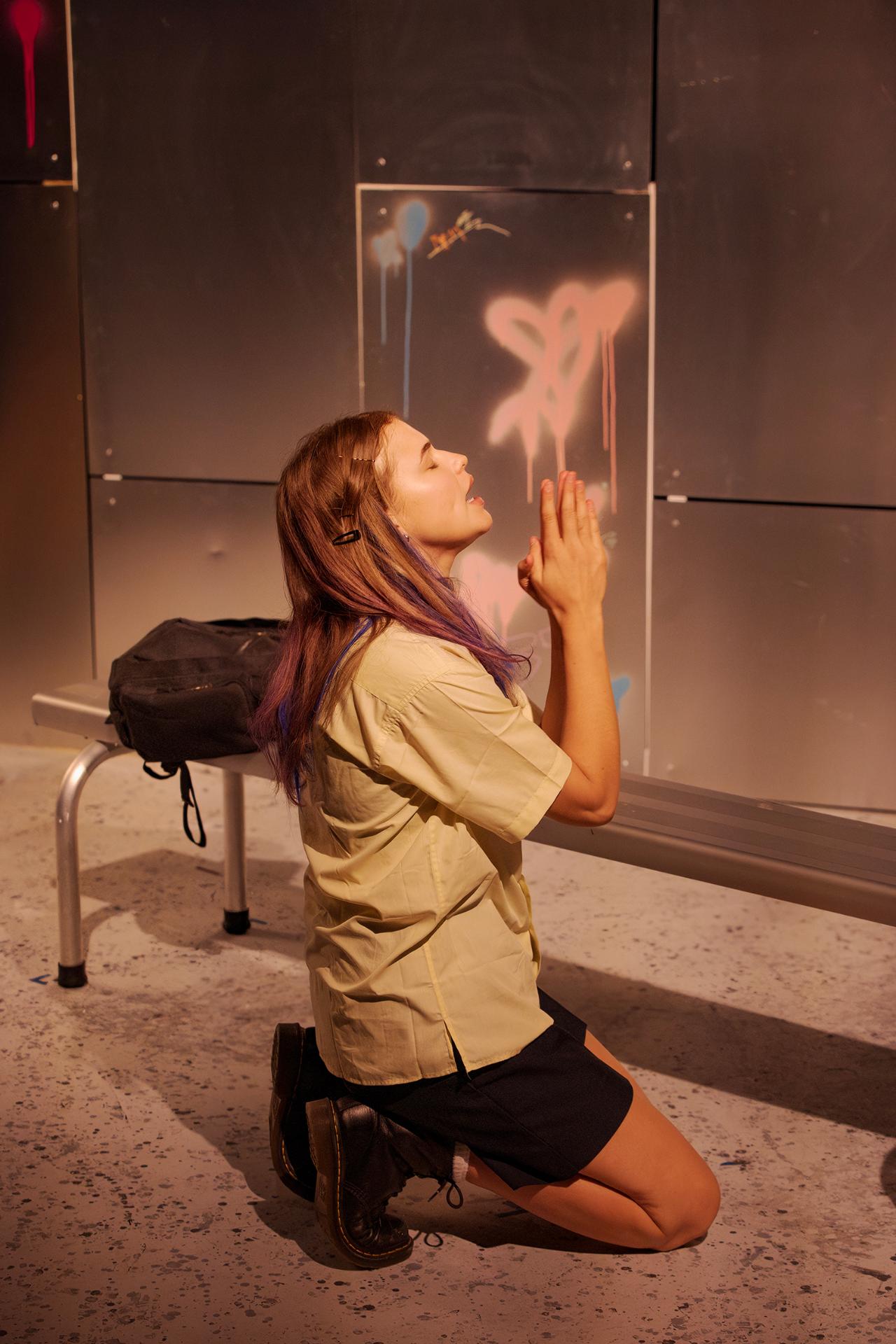

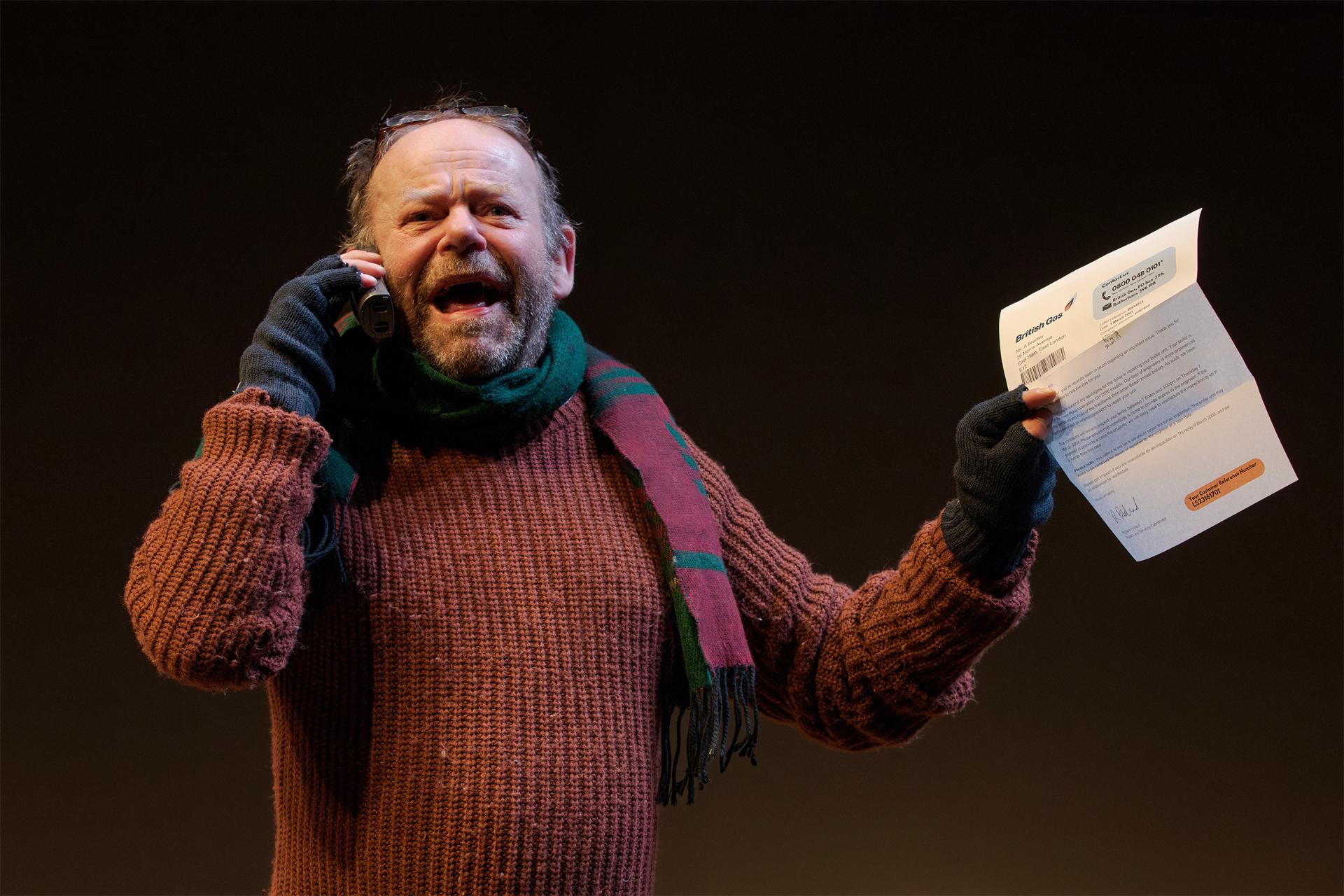

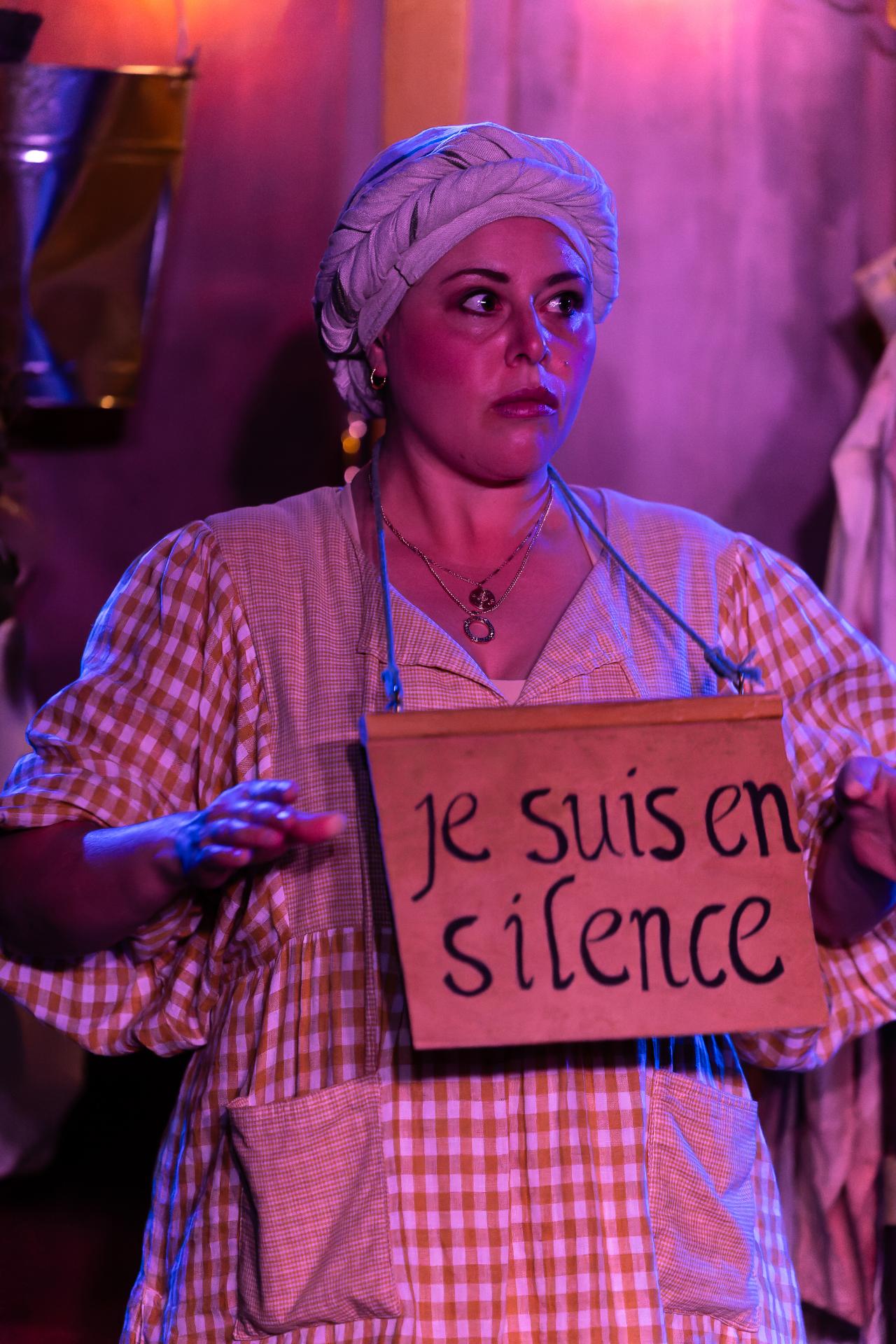

Images by Brett Boardman

Theatre review

Carmel Dean’s Well-Behaved Women (with additional lyrics by Miriam Laube) is a song cycle, with each number inspired by a remarkable woman from the annals of history, from Eve of the Garden of Eden, to Malala Yousafzai the British Pakistani activist. Whether mythical or simply legendary, these personalities all tell extraordinary stories of glorious ascendency, each one a brilliant example of tenacity and triumph.

The songs are uniformly enjoyable, thoroughly melodious to keep our attention and emotions engaged. Direction by Blazey Best delivers a show that reverberates with an unmistakeable sense of dignification for womanhood, although too persistently sombre for the 70-minute duration. Orchestrations by Lynne Shankel are powerful, but overly serious for much of the presentation. Lights by Kelsey Lee too are consistently grave, when we are in search for exaltation.

A cast of captivating singers takes us through this omnibus of exceptional women. Performers Stefanie Caccamo, Sarah Murr, Zahra Newman and Elenoa Rokobaro bring great verve, along with admirable polish, for a show memorable for its proud expressions of success and resistance.

Women are capable of great things, of course, but we are worthy even when we are unremarkable. Feminism is not only for those who are exceptional. In fact, it is more about those who are ordinary. We should all have the courage to behave badly and make history, but we need to remember that it will always be harder for some. It is impossible that we are all going to become iconic, not so much because of personal constitutions, but more because of circumstances. As we continue to love the characters in Well-Behaved Women, we need to understand that it is not only these anomalies that should be celebrated.