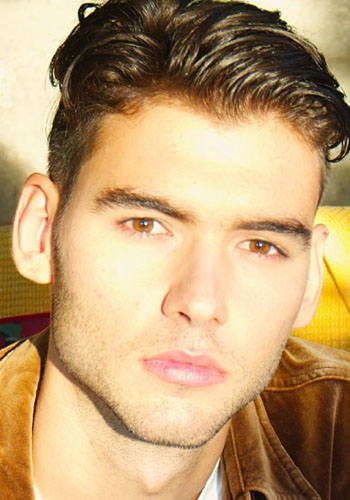

Declan Greene

I’ve admired Declan Greene’s writing for a while now. A distinctive sense of irreverence and adventure means that his shows are always unsettling, unpredictable and brilliantly controversial. Greene’s modernly queer perspective of our world generates a kind of outsider art that speaks to anyone who feels a little bit excluded, and I would suggest that that is all of us. For this special edition of 5 Questions, I attempt to find out how he ticks.

Suzy Wrong: I’d like to ask your age to put some context around your experience of growing up within a particular point of gay activism history, but don’t answer if you don’t wish to, ‘cos I sure as hell ain’t telling anyone my age.

I’m 32, and I grew up in rural Victoria with a lot of deep set homophobia at school, which I really internalised. Like, I was very visible screaming queen, so was called a fag a lot – and then I turned mean and vicious and started calling other kids fags – anyone who was smaller or weaker than me… So… Yeah. After high school I still really wrestled with identifying as ‘gay’ for a long time – even after I started sleeping with men – because I still thought gay culture was lame and embarrassing, all just Priscilla and Queer As Folk and fake tanner etc. Meeting Ash Flanders when I was twenty sort of changed my life, because he really showed me that being gay was this very customisable sort of thing – I could love punk and DIY and drag queens and super camp divas all at the same time, and actually there was a subset of queer culture that cherished all that dirty, faggy shit. That’s where my political identity was sort of formed.

Do you often use the terms “gay” and “queer” (or others) to describe yourself? Do they point to different parts of you, and how you relate to the world?

I have definitely used the term ‘queer’ to describe myself, but I’m becoming increasingly uncomfortable with it. I guess to me ‘queer’ is sort of like ‘punk’ – it’s not a fixed category, it’s a type of resistance. It exists in a state of constant flux, in opposition to whatever bad stuff is happening in the mainstream at the time. What’s queer now isn’t what was queer five years ago. And at the moment I feel like to be queer means to demolish binary thinking, and to embody fluidity, intersection, and inbetween-ness as a form of resistance. All of which I really believe in, politically speaking, but it doesn’t describe me socially… I sleep with men exclusively, and my gender is cis male… so maybe in 2017 I’m too binary to be queer? I don’t know. I guess I could say that I’m politically queer and socially gay – but I also probably wouldn’t say that, because the amount of energy consumed in that sort of elaborate navel-gazing self-identification makes me really anxious sometimes, in an era of Trump and Le Pen and Pauline Hanson!

Do you think all that insight and self-understanding is central to the purpose of your practise? What would you say the nature of your art is?

I tend to interrogate my position in relation to my subject matter quite a lot, because I’m often drawn to stories that centre on some kind of social oppression, but I exist in a space of relative privilege – as a white cis guy with a decent quality of life… so I always want to make sure that my interest in this material isn’t patronising or paternalistic or blah-blah-blah. It’s funny: I was brought up Catholic and sometimes I think that influences my work more than I’m conscious of… like, this deep sense of guilt about the stuff I’ve been lucky about. My only big struggles have been with my sexuality and money/class, so maybe my practice is about atoning for that on some level…? I don’t know, it’s complex too, because the artists and thinkers I admire are people like Jean Genet and John Waters and Joan Rivers and Camille Paglia and Nina Simone: genuine iconoclasts, who never gave a fuck what people thought of them, who never felt guilty or apologetic or beholden to the opinions of others. So that’s the push and pull in my art always: like, trying to muster up the bravery to say what I really think or feel, while trying to minimise harm to people who might be more vulnerable than me.

How do you imagine your audience? What do they look like in your ahead? Do you write for a particular type of person?

I try not to imagine the audience as one big organism, because it’s obviously full of many varied people, all coming at the work from an incredible diversity of perspectives and lived experiences. With something like The Homosexuals, Or Faggots, which is located in a very specific part of the LGBTIQA+, there’s always the temptation to take shortcuts and assume that the audience will have a common understanding of the political terrain you’re addressing – but I always try to imagine the audience is coming to these issues totally fresh, and write a fair bit of context into the play.

Are you consciously political or subversive in your process? I suppose I’m asking, if it all needs to make a point? Is it a burden?

The politics in my shows are definitely conscious, but it’s not really a burden to include them because in a lot of ways they’re actually my starting point. There has to be some sort of formal challenge, plus a line of political enquiry I’ve got a burning desire to follow – something big and furious enough that it that can sustain me over the year or more it takes to conceive and write and redraft a new play. With The Homosexuals, Or Faggots I’d had this idea in the back of my mind for a long time that I’d like to try writing a farce, but I didn’t really know why yet – there was no impetus to begin. Then I read a weird semi-mocking article about a Caitlyn Jenner Halloween costume on a big gay news website – like Gaily Grind or something – which threw up a bunch of questions for me about privilege, freedom of speech, political correctness, allyship, and the responsibilities white gay cis men have to the wider LGBTIQA+ community. And the two notions just sort of clicked together: a farce set in the world of queer identity politics.

The Sydney season of Declan Greene’s The Homosexuals, Or Faggots, is presented by Griffin Theatre Co.

Dates: 17 March – 29 April, 2017

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre

Venue: Hayes Theatre Co (Potts Point NSW), Mar 8 – Apr 1, 2017

Venue: Hayes Theatre Co (Potts Point NSW), Mar 8 – Apr 1, 2017

Venue: Old Fitzroy Theatre (Woolloomooloo NSW), Feb 28 – Mar 11, 2017

Venue: Old Fitzroy Theatre (Woolloomooloo NSW), Feb 28 – Mar 11, 2017 Venue: Roslyn Packer Theatre at Walsh Bay (Sydney NSW), Feb 28 – Apr 1, 2017

Venue: Roslyn Packer Theatre at Walsh Bay (Sydney NSW), Feb 28 – Apr 1, 2017

Venue: The Riverbank Palais (Adelaide SA), Mar 6 – 8, 2017

Venue: The Riverbank Palais (Adelaide SA), Mar 6 – 8, 2017 Venue: Festival Theatre (Adelaide SA), Mar 3 – 9, 2017

Venue: Festival Theatre (Adelaide SA), Mar 3 – 9, 2017 Venue: Her Majesty’s Theatre (Adelaide SA), Mar 3 – 9, 2017

Venue: Her Majesty’s Theatre (Adelaide SA), Mar 3 – 9, 2017 Venue: ATYP (Walsh Bay NSW), Mar 1 – 3, 2017

Venue: ATYP (Walsh Bay NSW), Mar 1 – 3, 2017