Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Feb 17 – Apr 5, 2025

Playwright: Tom Wright (from the novel by Joan Lindsay)

Director: Ian Michael

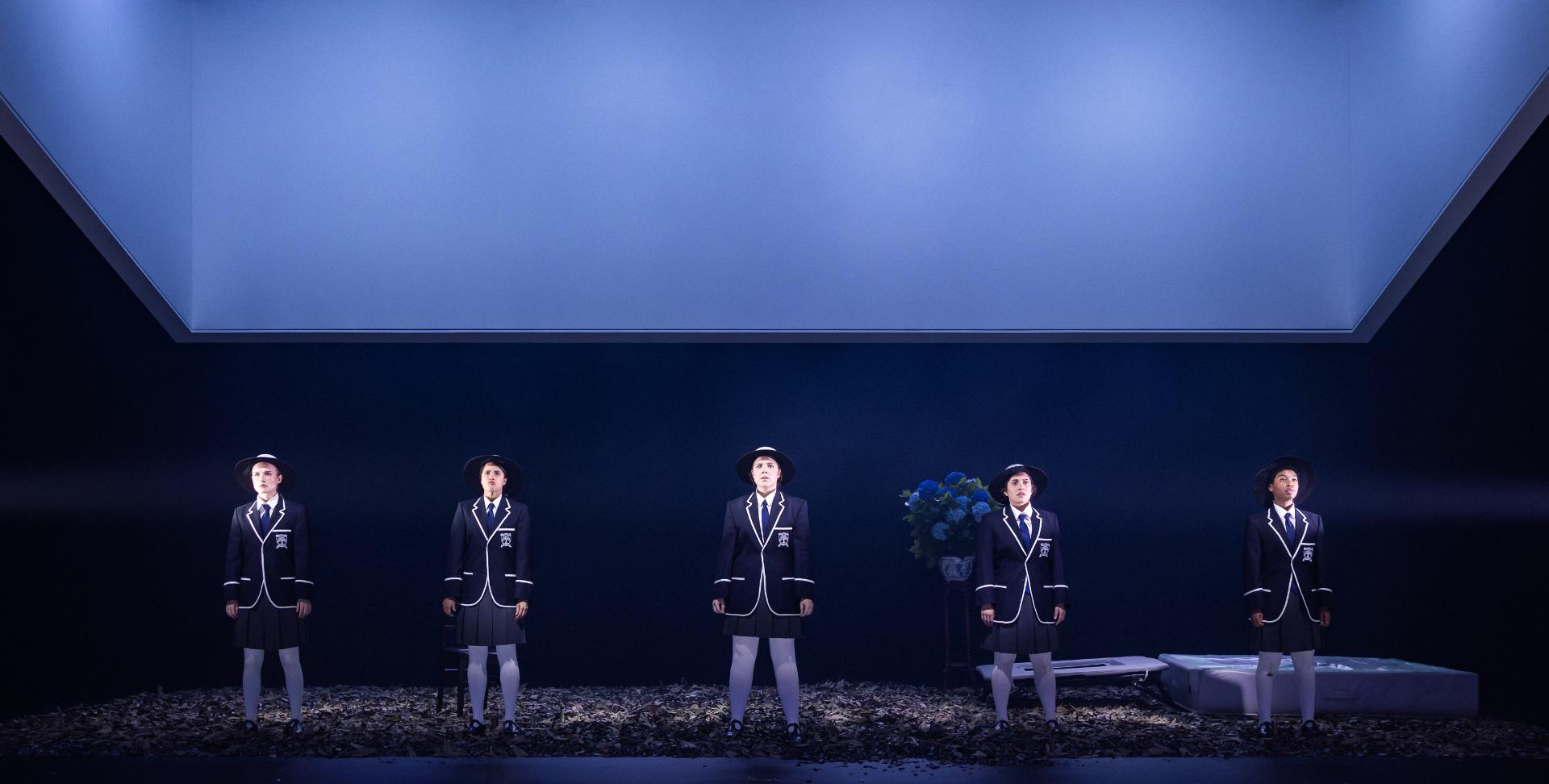

Cast: Olivia De Jonge, Kirsty Marillier, Lorinda May Merrypor, Masego Pitso, Contessa Treffone

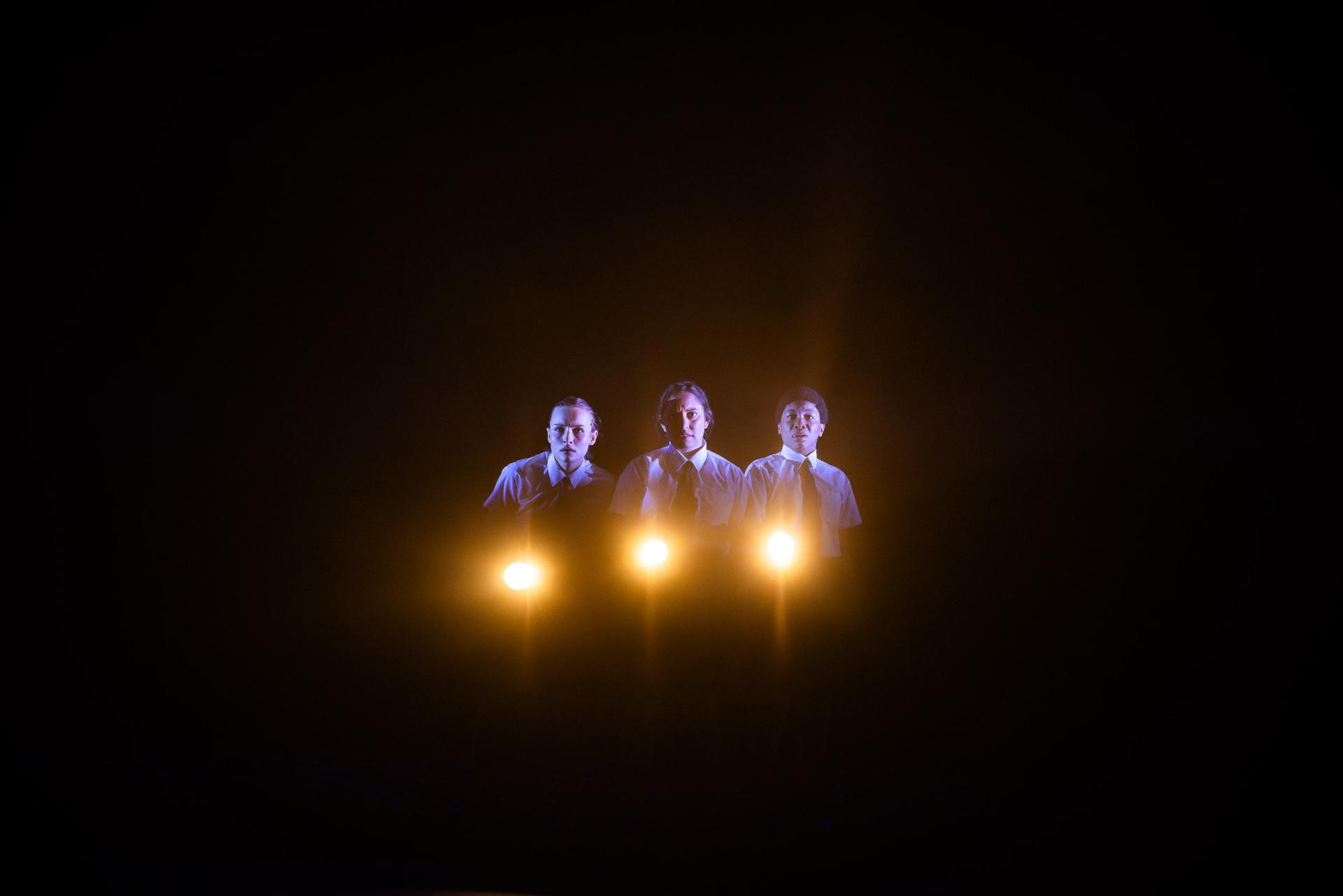

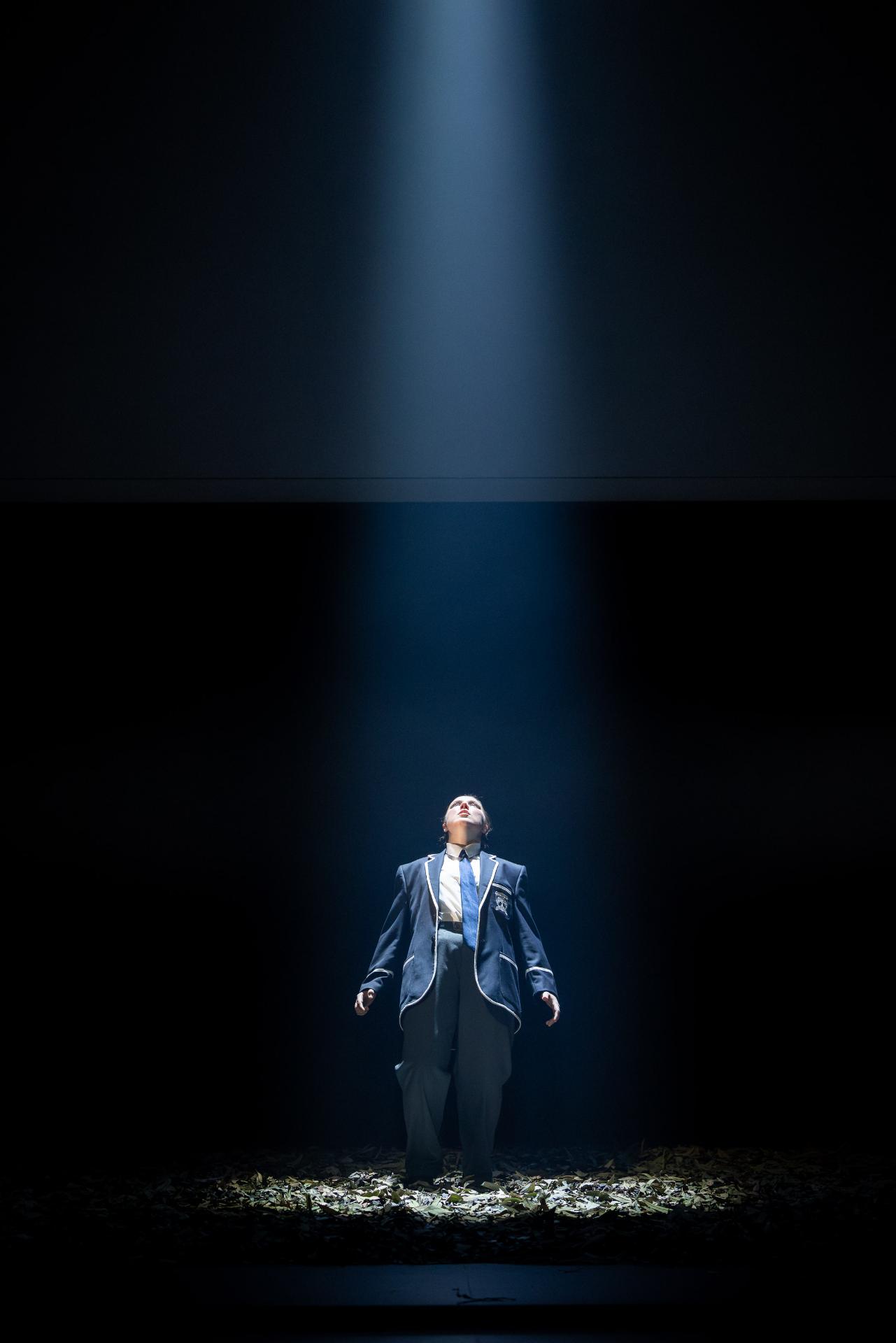

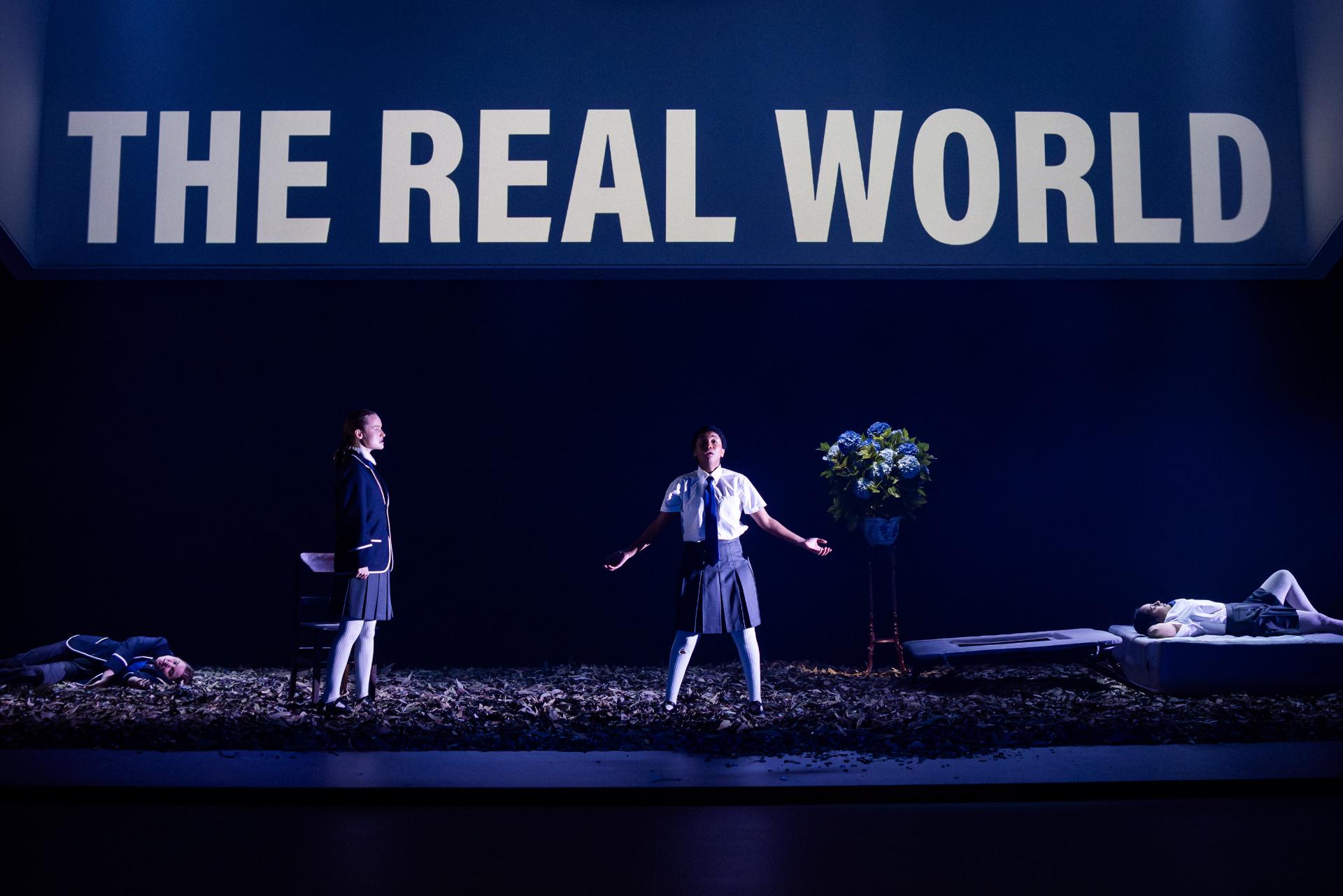

Images by Daniel Boud

Theatre review

Joan Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock, is likely the most famous story ever told about this land exacting revenge on its inhabitants. Since the time colonisers deemed it fit to declare terra nullius and named her Australia, European settlers and their descendants, have always borne a pang of guilt in their conscience. They know something is not quite right about the ways they have claimed this their own, and much as they often try to deny the unjust displacement of Indigenous peoples, the truth always finds a way to strike back.

In Tom Wright’s magnificently theatrical stage adaptation of Lindsay’s novel, we are able to observe tangibly, the concurrent effects of both metaphysical and psychological consequences, of land being stolen. The monolith at the centre of Picnic at Hanging Rock serves as symbolic projection, for those unable to acknowledge the actual dilemma, and therefore enact a series of horrors onto their own bodies, as though emanating from that geological feature. Also valid however, is the interpretation that the monolith is in fact sentient, and is executing tactics of protection, in attempts to right those historical wrongs.

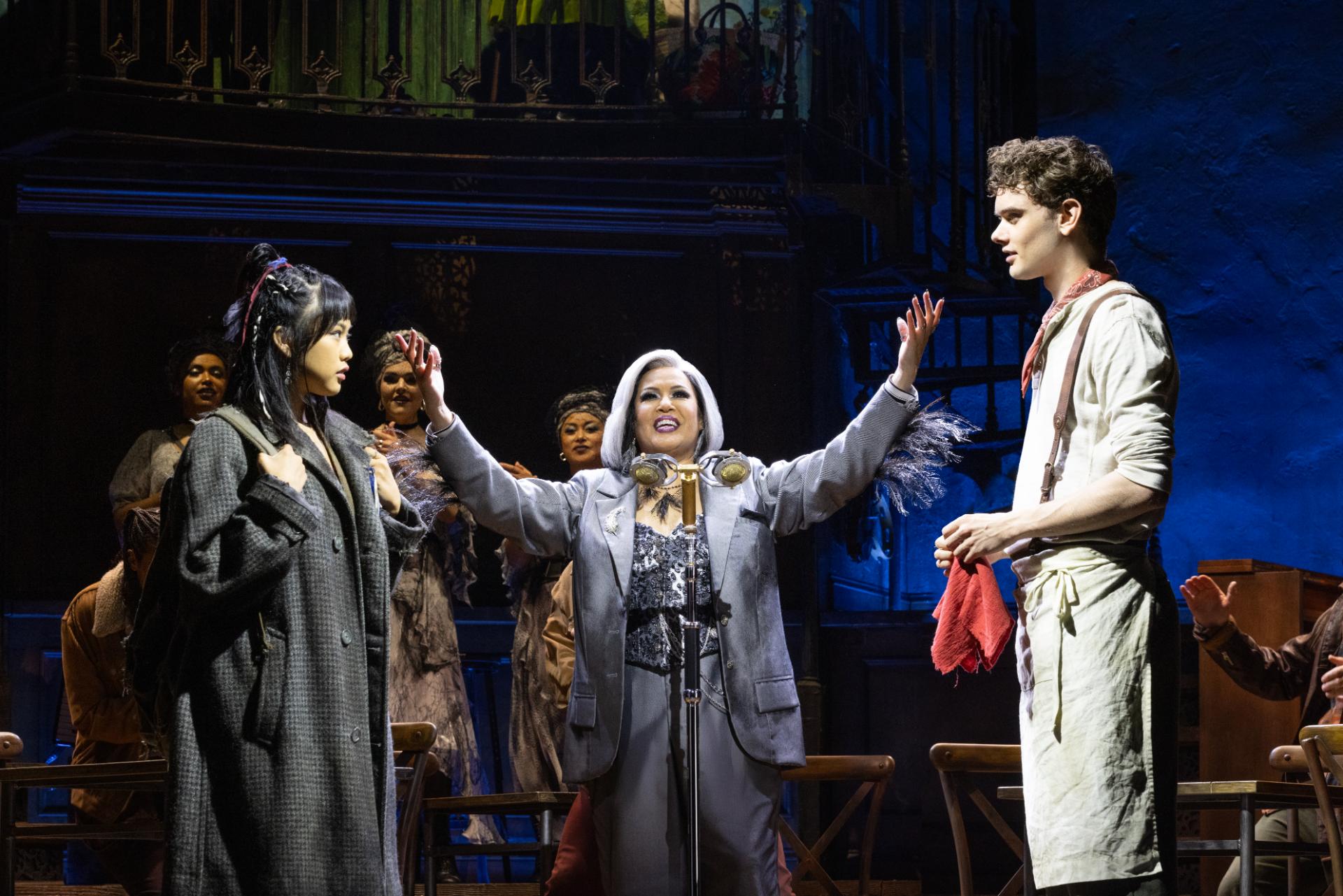

Ian Michael’s direction offers all the possibilities, enabling viewers to draw personalised conclusions that would resonate most intimately. Built into the production are a great variety of sensorial textures and psychic dimensions, resulting in a work ambitiously vast, not just in its sheer experiential capacity to leave us breathless and overwhelmed, but also in its scale of representations. Michael’s artistry ensures that everything is laid out to be seen, yet nothing is ever forced; we are presented all the details, and left to consume what we can. Picnic at Hanging Rock is as horrifying as you would allow, as funny as you want, and as political as you are ready to accept.

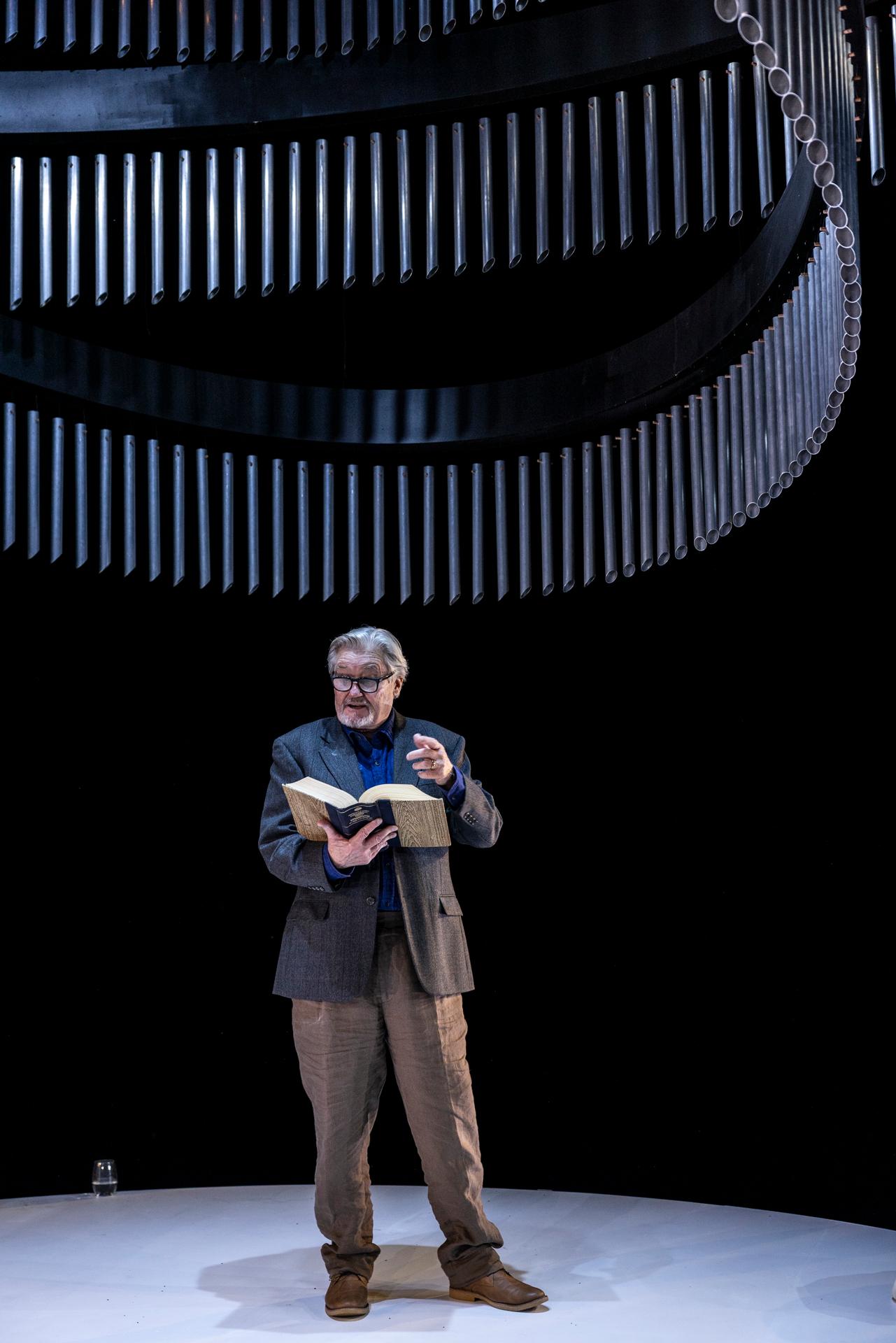

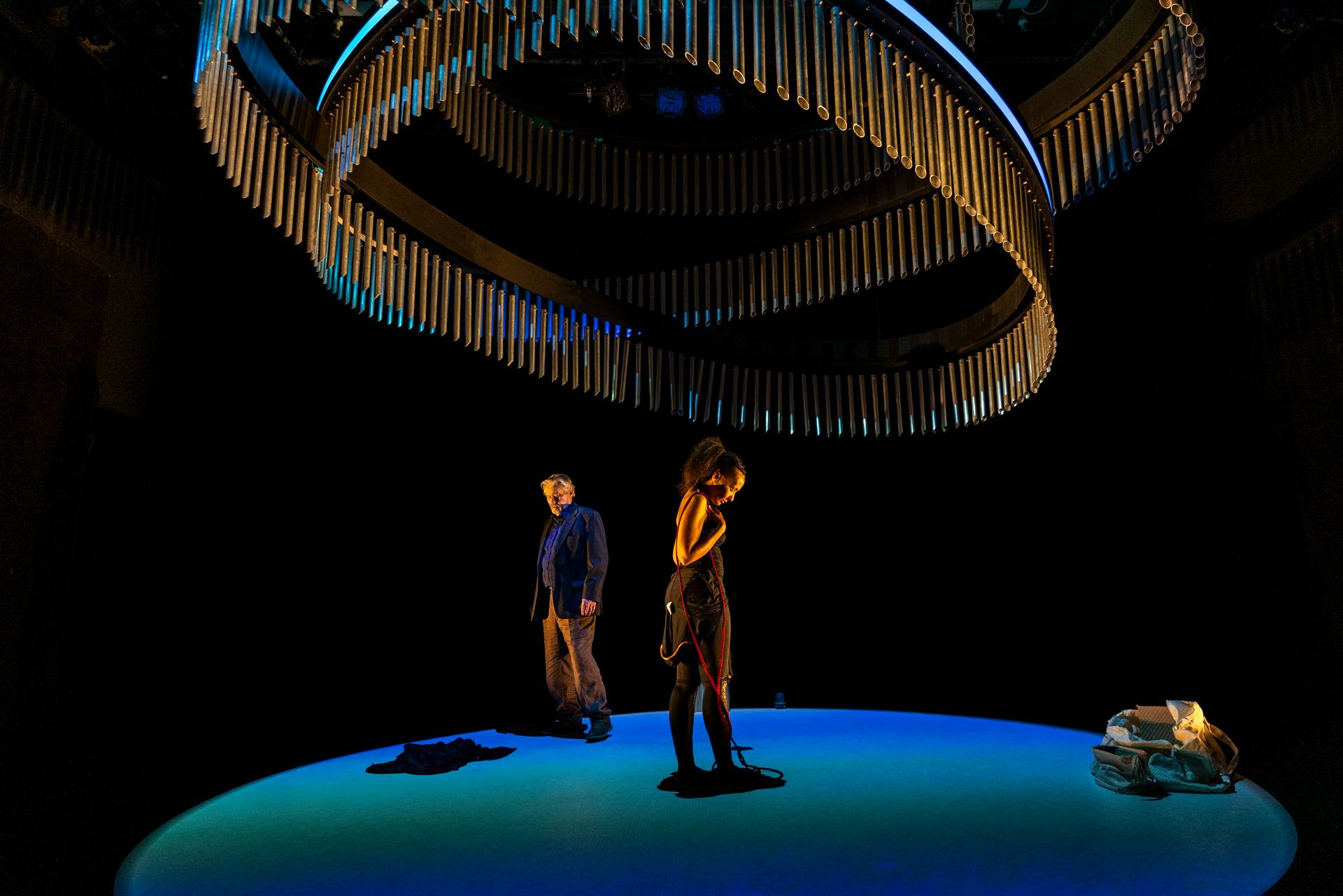

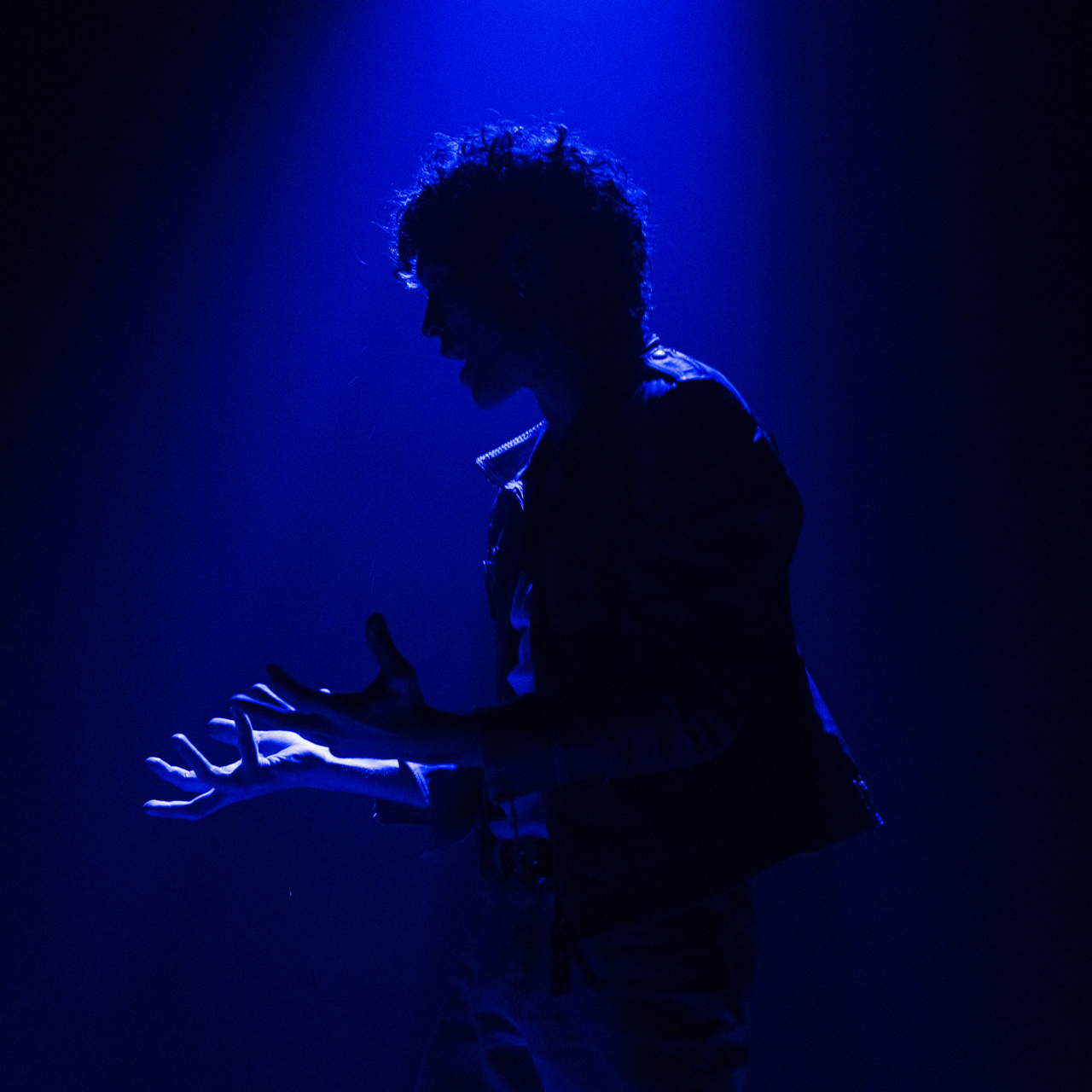

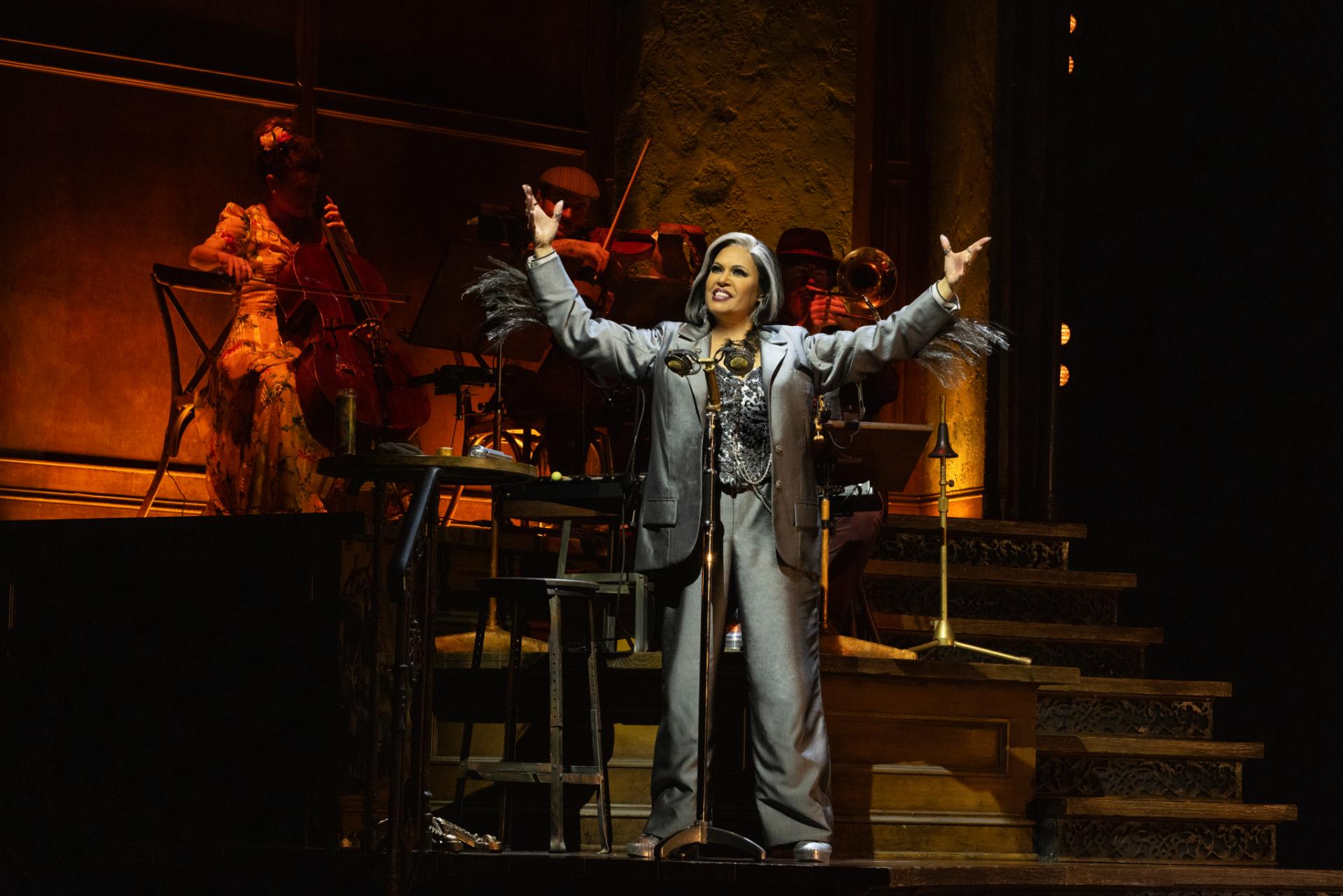

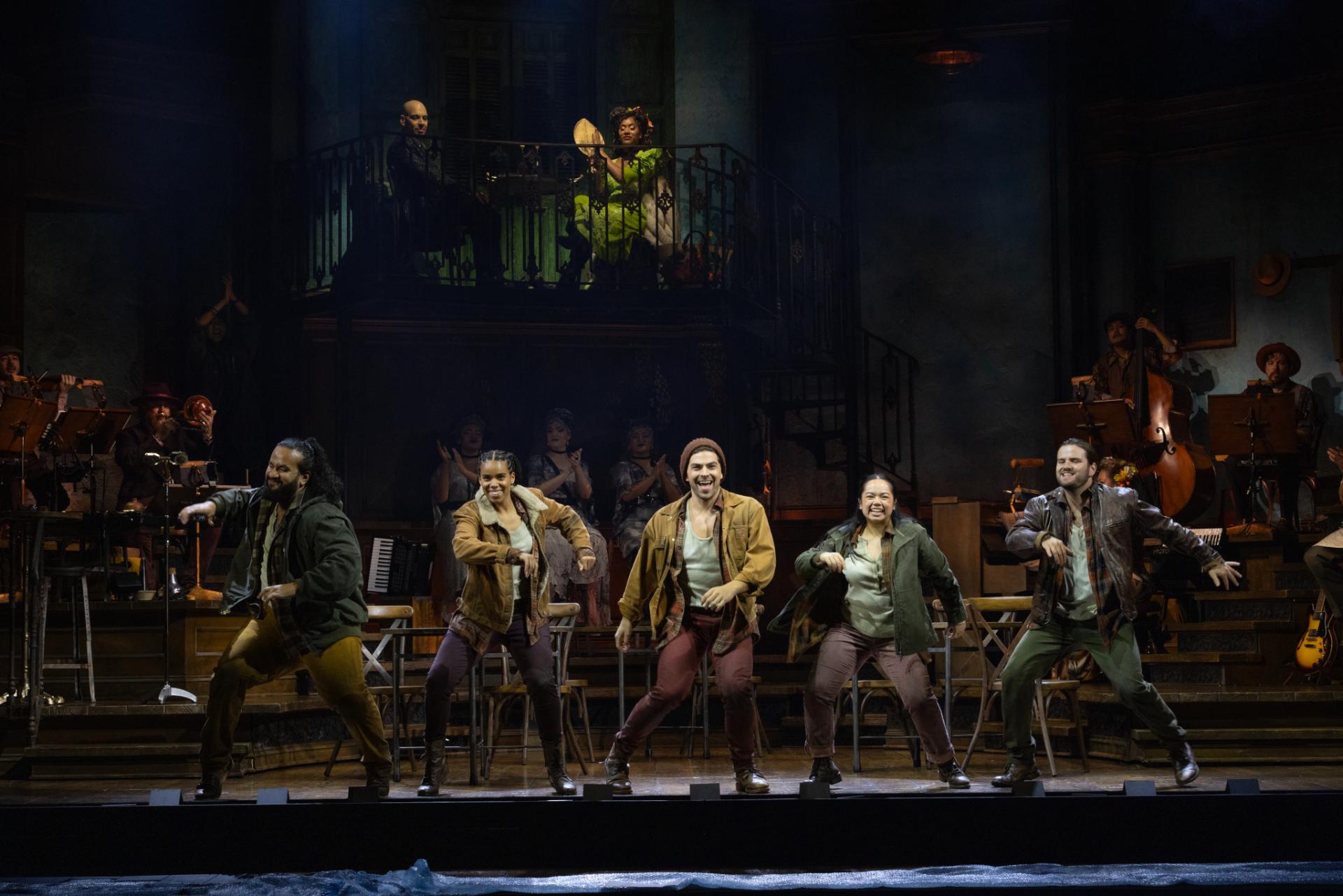

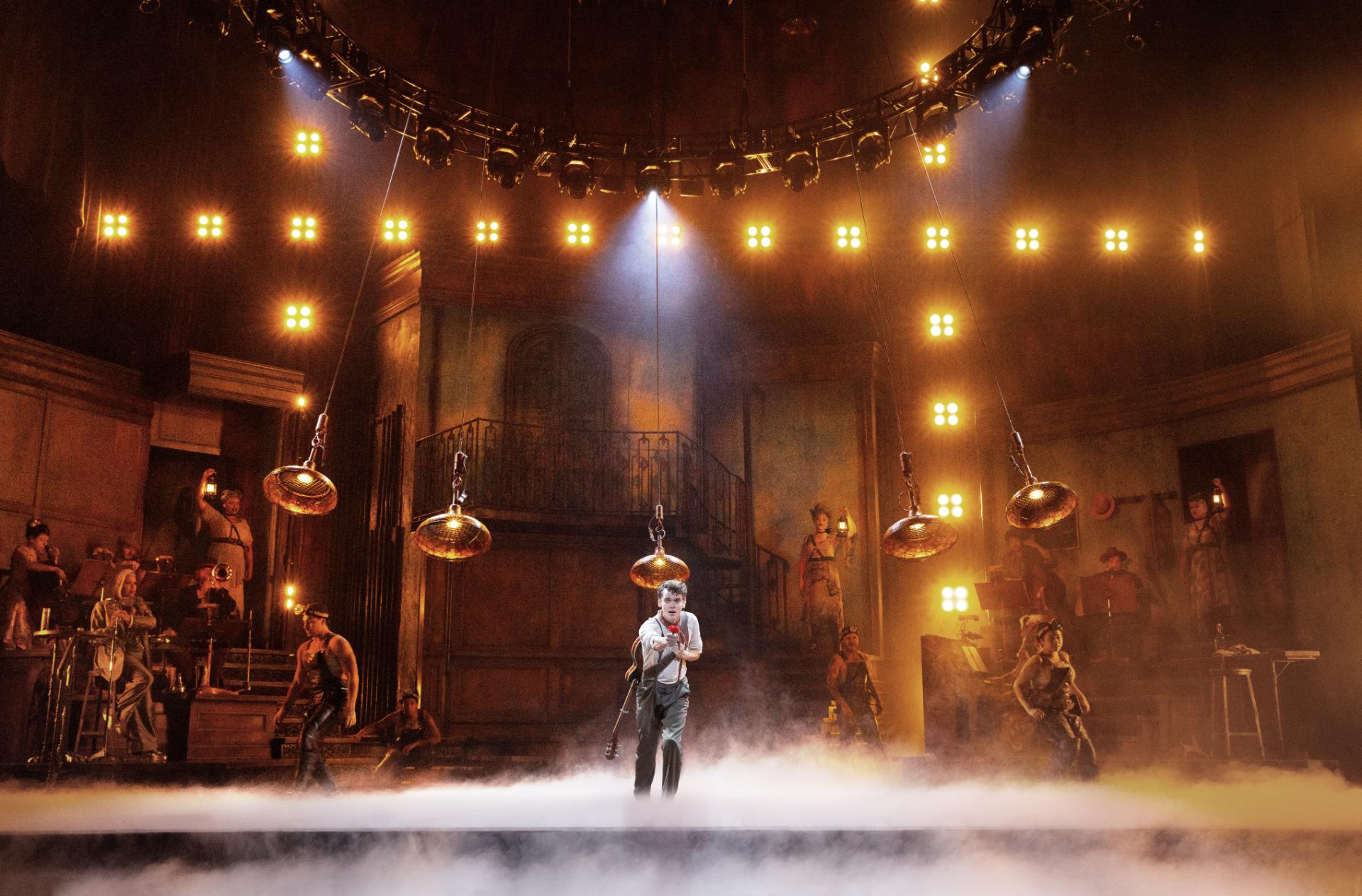

Dominant in the set design by Elizabeth Gadsby is a raised and tilted structure, that looks as though a proscenium arch has eerily shifted upward, subsequently pouring its contents onto the earth. Imposing like the rocks of Dja Dja Wurrung country, whilst demonstrating the vexing presence of Western structures that cannot hold. Lighting by Trent Suidgeest is an exciting element, extravagant in sensibility but consistently tasteful in execution, and memorable for being absolutely electrifying at the most dramatic instances. Exquisite sounds by James Brown are flawlessly orchestrated to usher us not only to the year 1900, but also through various membranes of reality, so that we encounter realms beyond the mundane, that seem to have always existed, but are rarely accorded due attention. Picnic at Hanging Rock is greatly concerned with what we cannot see, all of which is translated on this occasion, into everything that we can hear.

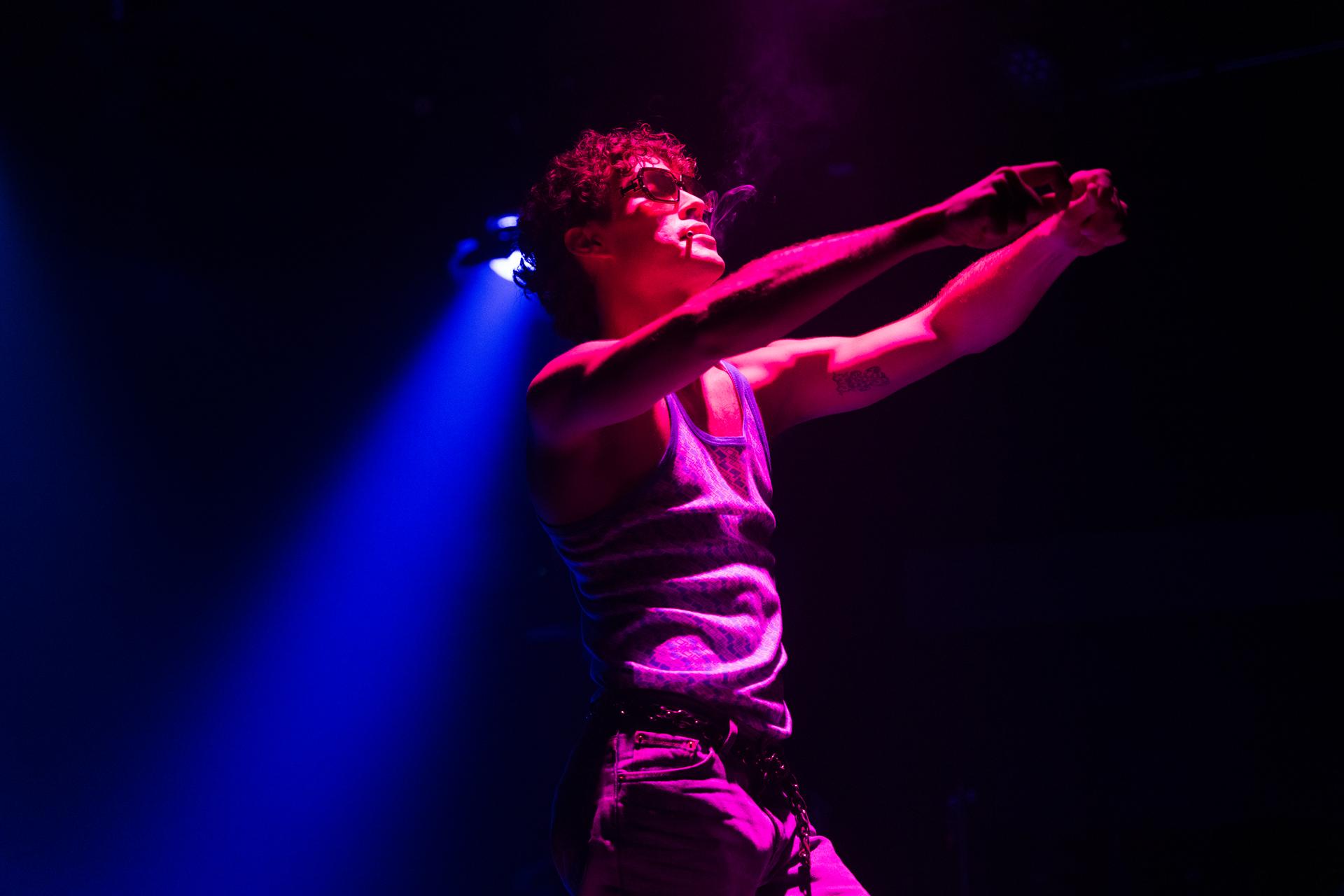

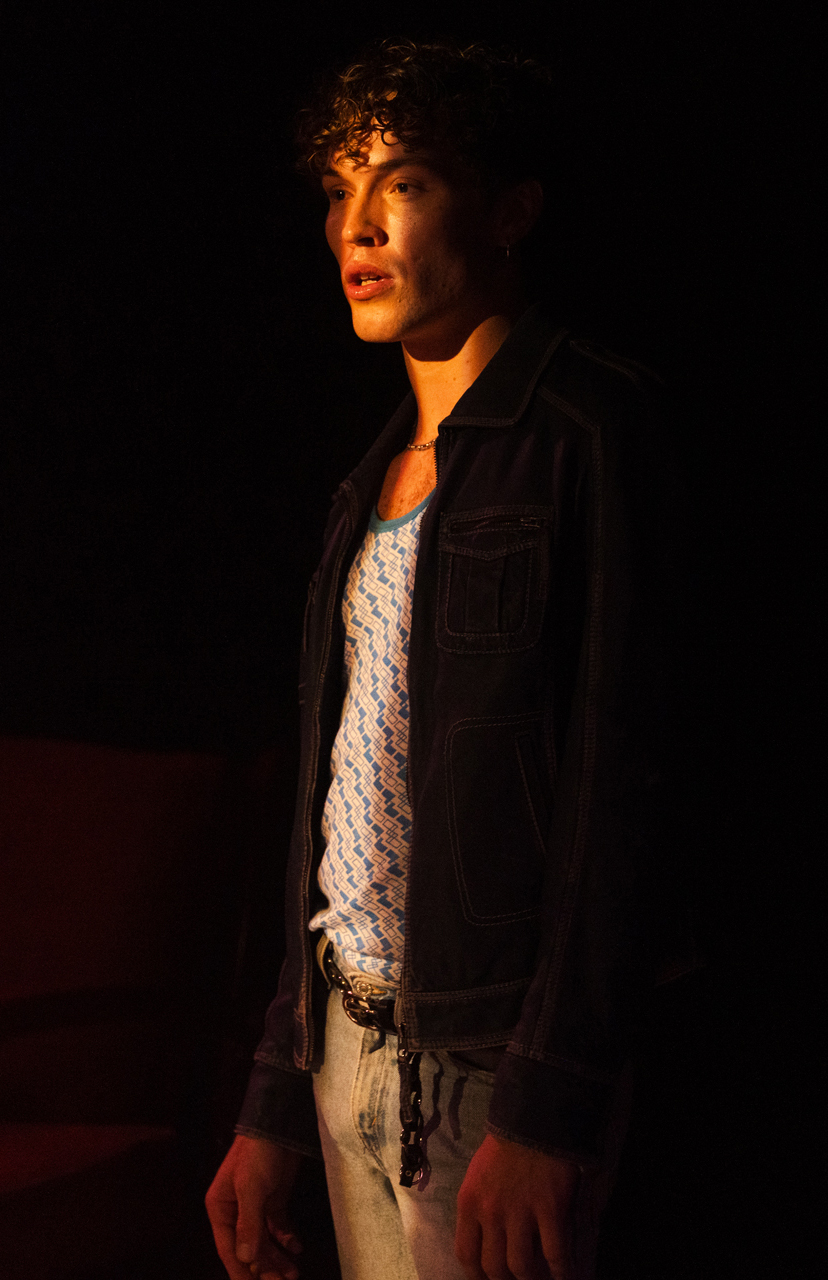

An astonishing ensemble of five extraordinary performers, namely Olivia De Jonge, Kirsty Marillier, Lorinda May Merrypor, Masego Pitso and Contessa Treffone, deliver a 90-minute show that is always urgent, and never predictable. They play naturalism one moment, then seamlessly transition to the most heightened of expressions the next, fully embodying both the sociological and the macabre aspects of their narrative. The women’s thrilling inventiveness is awe-inspiring, and the depth and gravity they reveal for this important instalment of our modern literary canon, is likely paradigmatic.

Something magical occurs when art precipitates transcendence. Call it healing, catharsis, or even exorcism, art can offer enlightenment in ways beyond the capacities of conventional language. This staging of Picnic at Hanging Rock leaves one feeling like they had been grabbed tight and shaken vigorously. An intense sensation is instilled, but what it communicates may not be immediately clear or explicitly understandable. Art will change people, and when it stokes the fire of human conscience, is when it serves its most noble purpose.

www.sydneytheatre.com.au