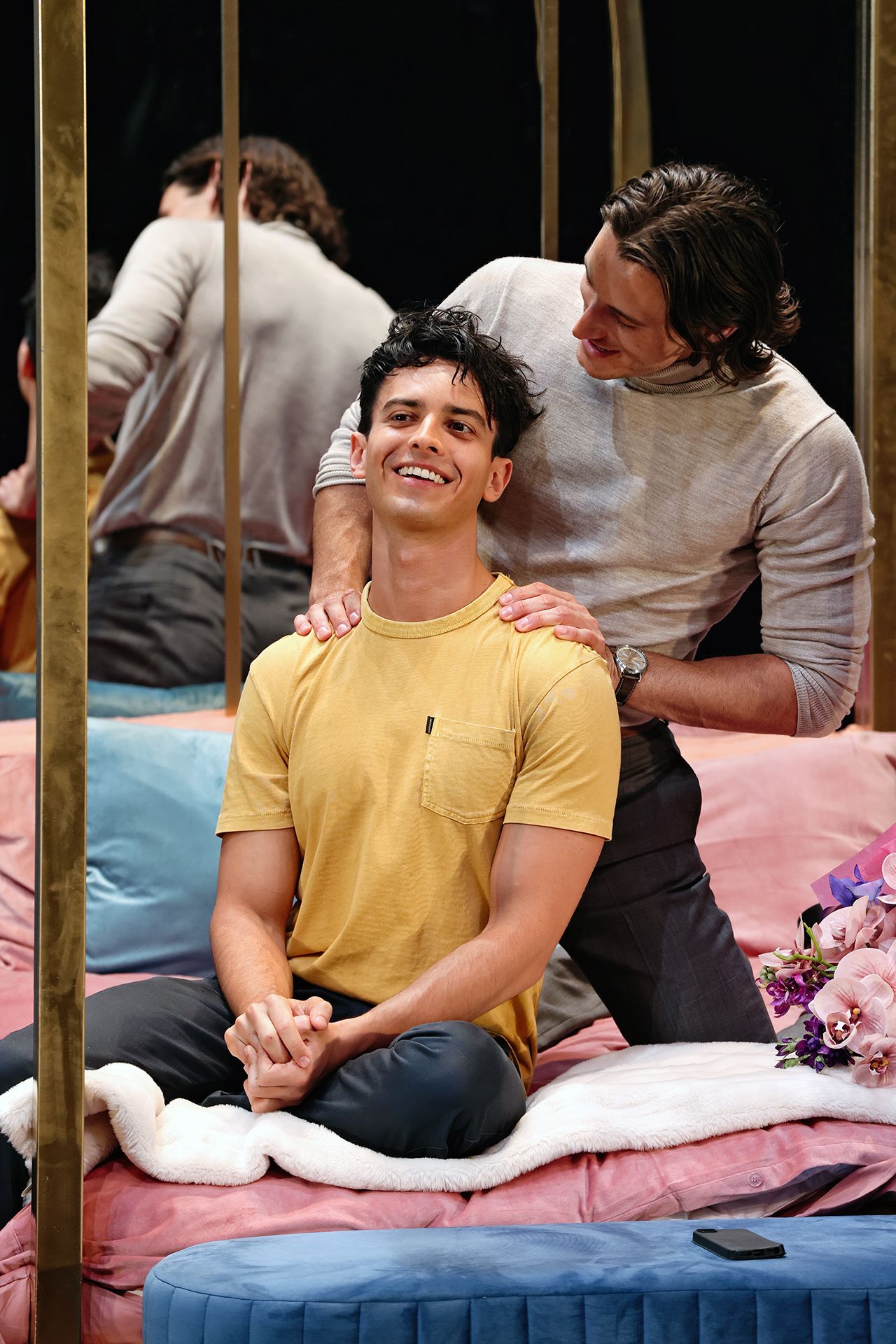

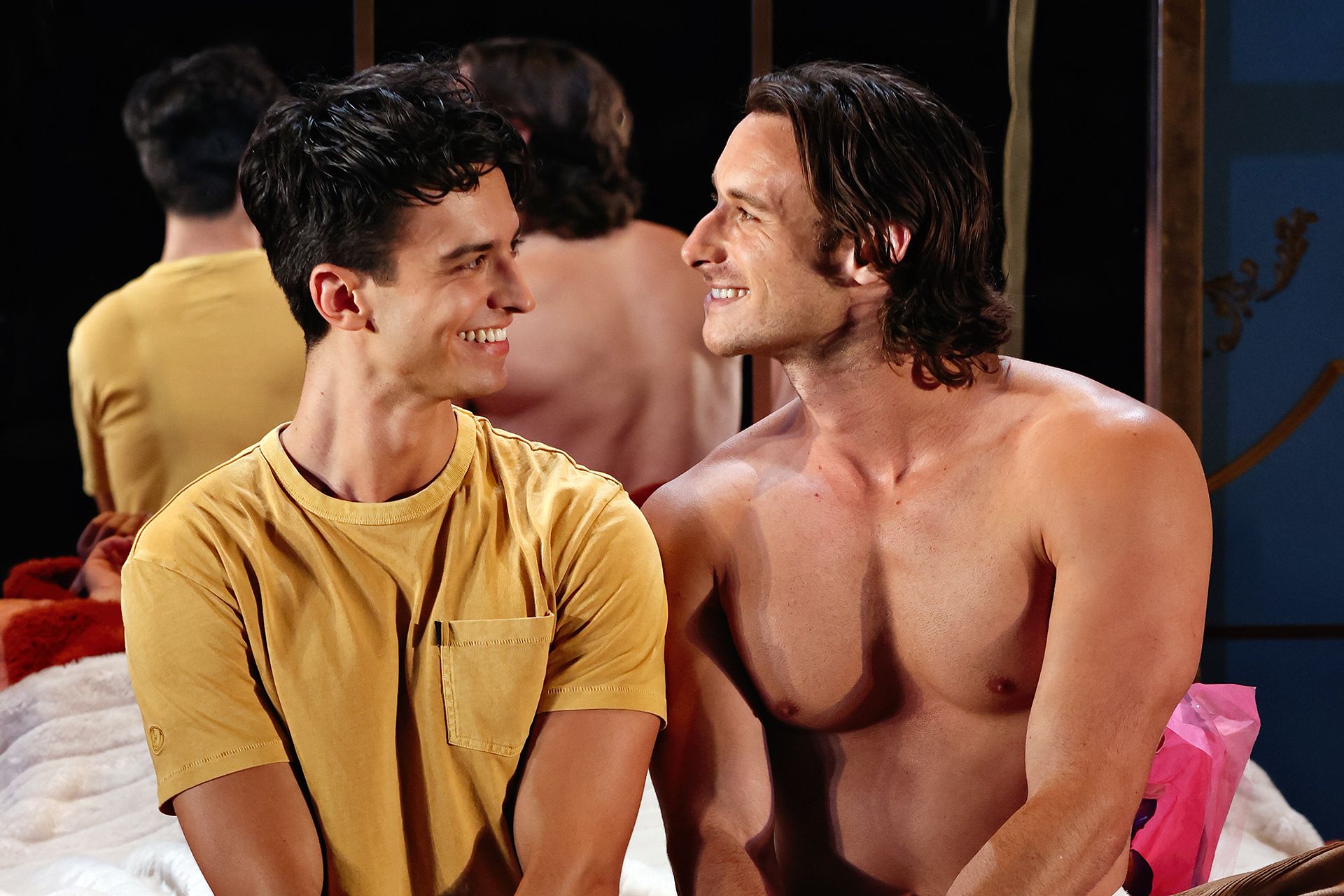

Venue: Wharf 1 Sydney Theatre Company (Walsh Bay NSW), Jun 8 – Jul 15, 2023

Playwright: Anchuli Felicia King (based on the novel by Wong Shee Ping, translated by Ely Finch)

Director: Courtney Stewart

Cast: Ray Chong Nee, Hsin-Ju Ely, Silvan Rus, Shan-Ree Tan, Merlynn Tong, Kimie Tsukakoshi, Anna Yen, Gareth Yuen

Images by Prudence Upton

Theatre review

Sleep-Sick appears from the very beginning, as a ghost with his throat brutally slit, indicating that things do not end well. In the 1909 novel The Poison of Polygamy《多妻毒》by Wong Shee Ping 黃樹屏, our narrating protagonist tells his epic story, of journeys between Guangdong in China, and Victoria in Australia, during the goldrush era. We soon discover that it was Sleep-Sick’s opium habit that instigated this riveting chain of events, one that Wong had undoubtedly conceived as a moralistic tale. Involving sins of greed and debauchery, The Poison of Polygamy is typical of traditional Chinese attitudes, in a style that is not unlike many classics charting a man’s downfall, following his failure to abstain from depravity.

In Anchuli Felicia King’s stage adaptation however, the moral centre is shifted from personal foibles, to an emphasis on deficiencies that are cultural and systemic in nature. Sleep-Sick’s narrative now operates as allegory, in a play that demonstrates undeniable interest, in the nature of capitalism and the detrimental effects of colonialism. King’s reshaping of The Poison of Polygamy is thereby turned into something much more pertinent to our times, one that addresses our unmitigating concerns around the idea of a decline in this civilisation. All the amusing salaciousness that feature in the original is however gloriously retained. Money, sex, and murder are key ingredients, in a show that explores our most primal and unchanging desires.

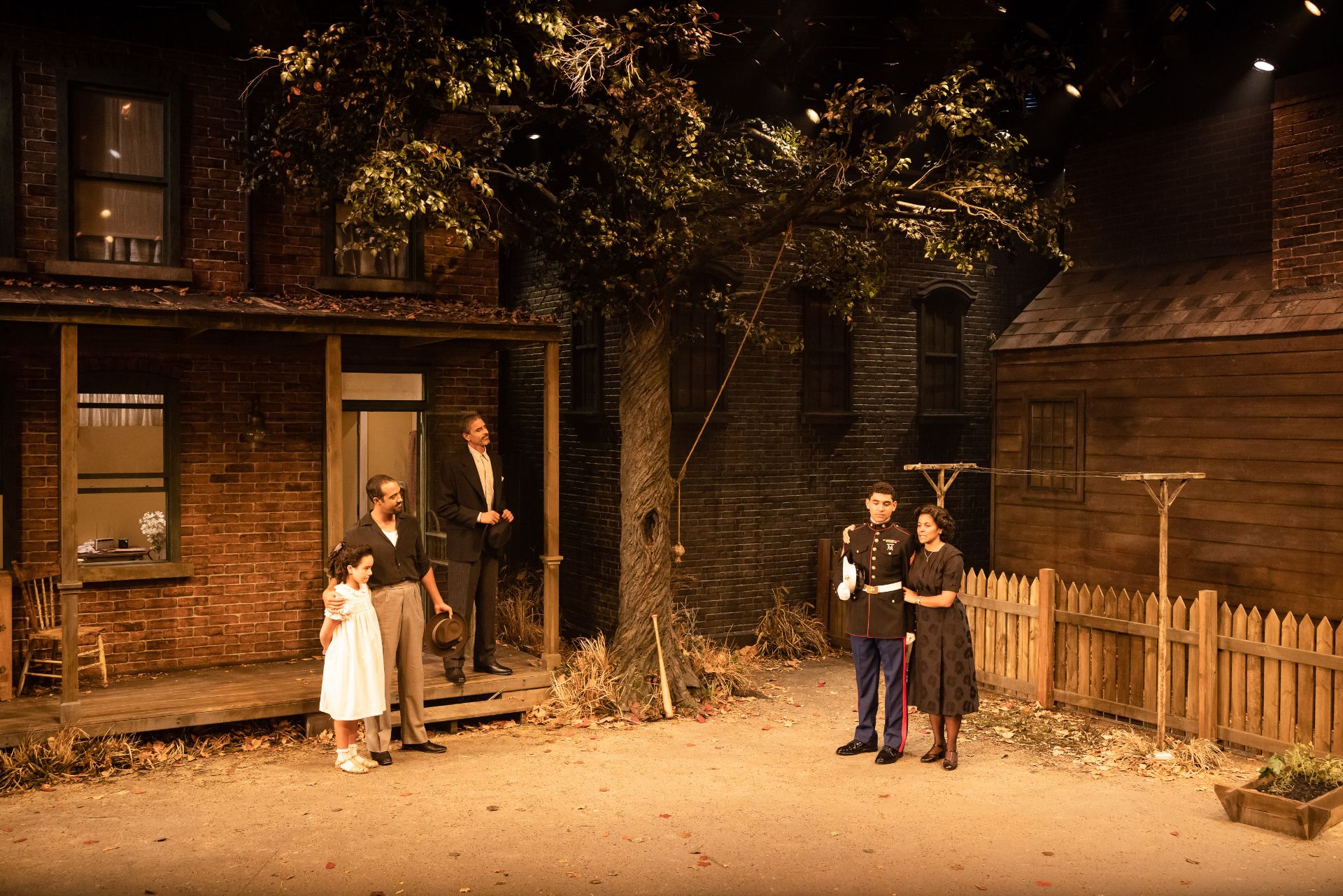

The production satisfies on many levels, under the astute directorship of Courtney Stewart, who utilises fully the text’s numerous dimensions, to deliver a complex and thoroughly engrossing work of theatre. Highly innovative and wonderfully imaginative, Stewart transforms an empty stage into exciting scenes, offering an experience that pulsates with a continual sense of anticipation as a result of its unpredictability, and disarming with its scintillating sardonic humour.

James Lew’s design is thankfully only elementally evocative of what might be considered a Chinese aesthetic, able to circumvent the cliché of chinoiserie, whilst creating imagery that look commensurate with how we believe this world to have been. Lights by Ben Hughes are rigorously conceived, agile in shifting us between distinct spaces, and powerful at manufacturing atmosphere. Music by Matt Hsu couches the action in an air of authenticity, and along with sound design by Guy Webster, engage our hearing for a consistent feeling of enrichment, subconsciously perhaps, that boosts our enjoyment.

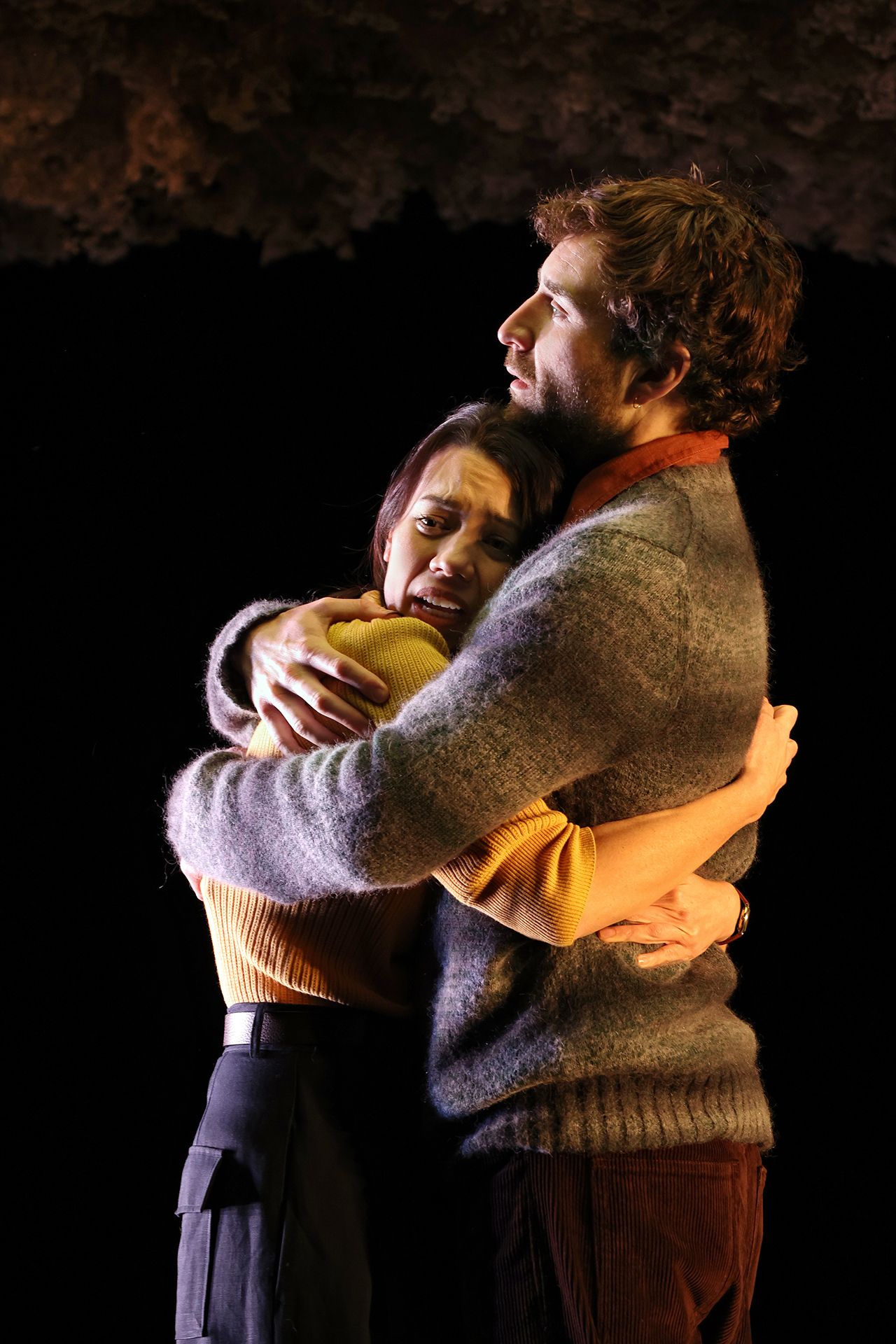

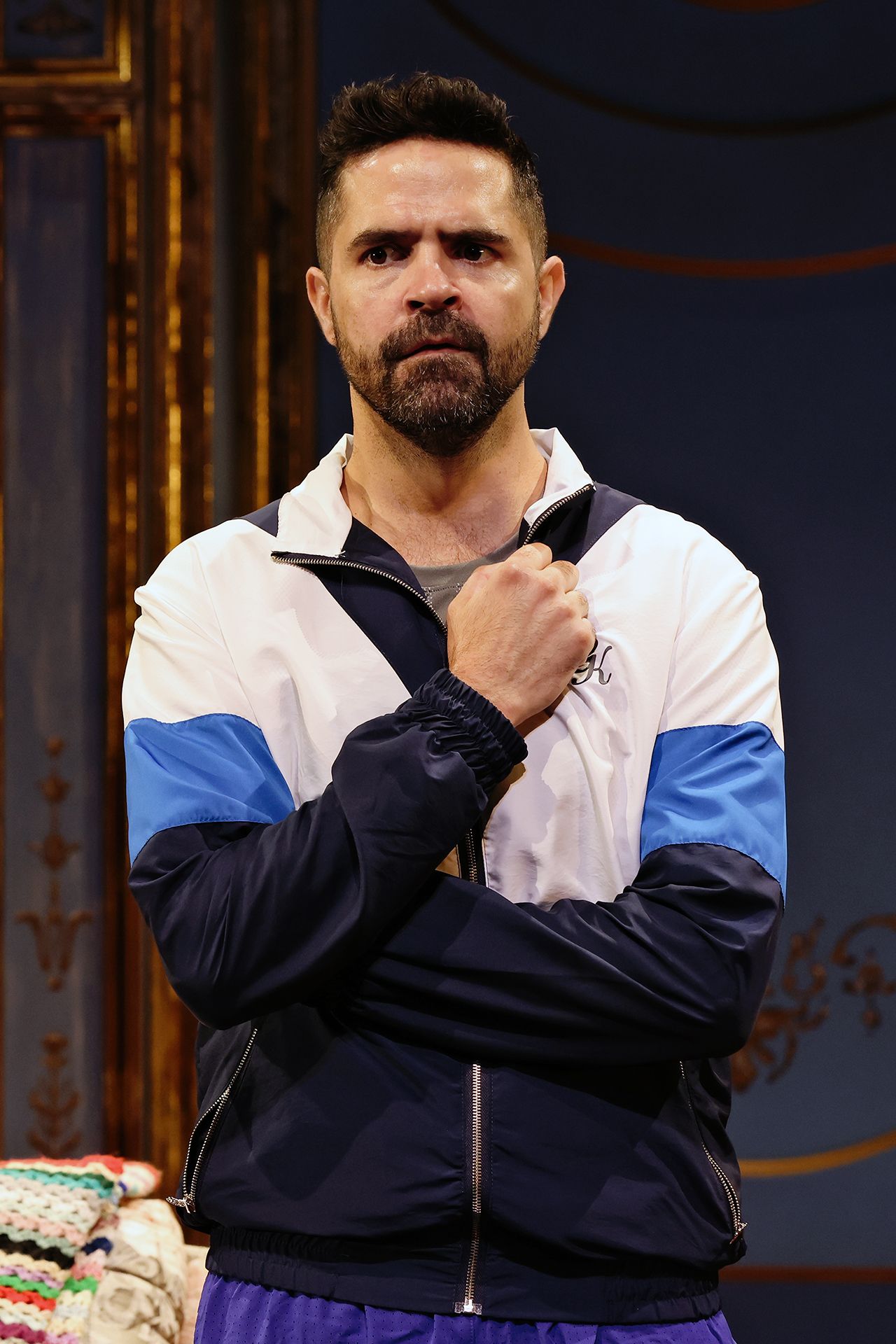

Actor Shan-Ree Tan is an extraordinary leading man, totally captivating with his intricate depictions of and commentary on Sleep-Sick, successfully transforming a character with many flaws into a person we are desperate to know everything about. Kimie Tsukakoshi plays femme fatale Tsiu Hei with delicious aplomb, stunning in her unapologetically grand portrayal of the seductive villain, somehow never descending into caricature, and always able to provide psychological rationale for all the outrageous behaviour.

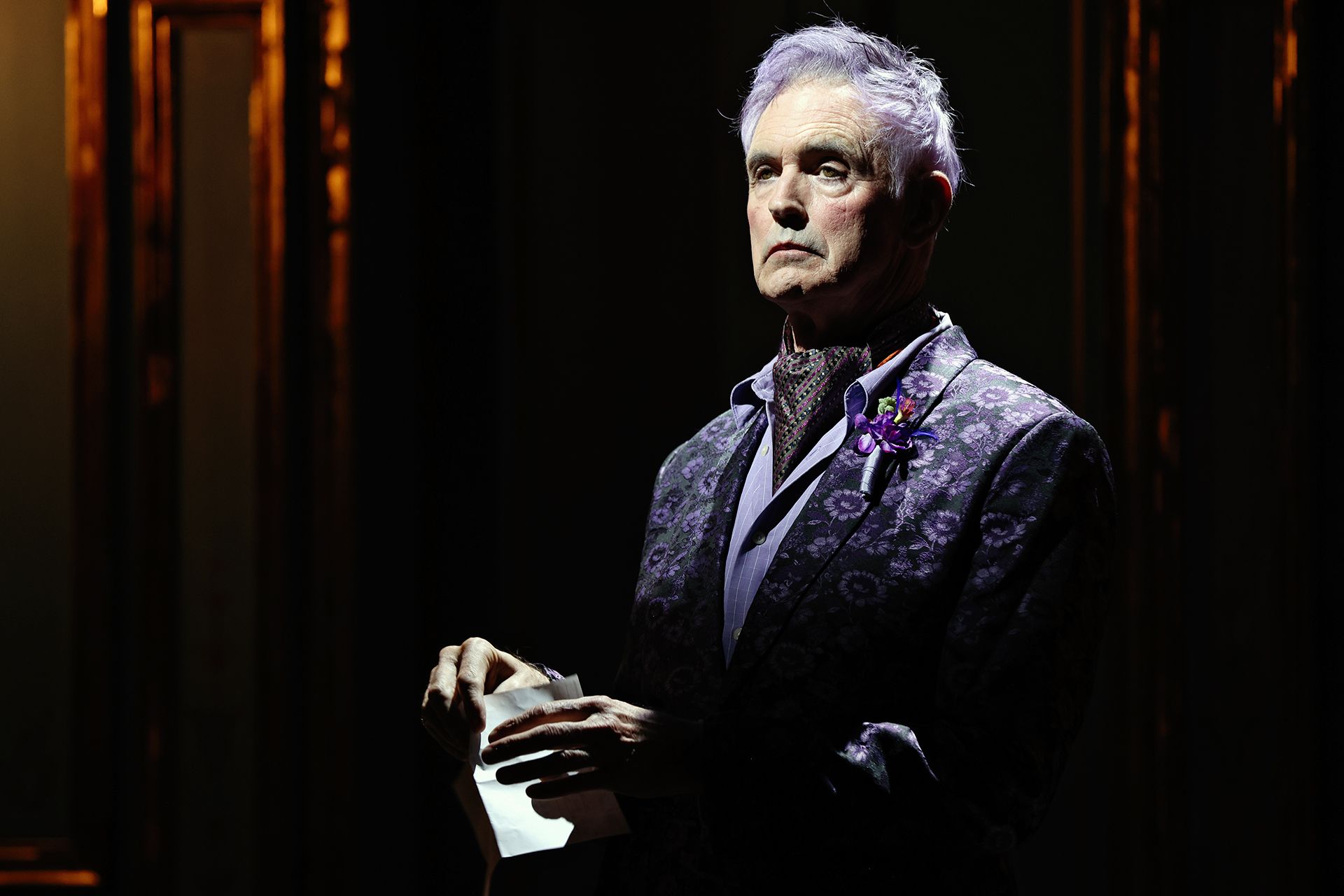

Sleep-Sick’s long suffering wife Ma is made dignified by Merlynn Tong’s mettle and spirit. Her capacity to represent both the hardest and softest aspects of the old-fashioned Chinese woman, conveys an admirable defiance alongside the inevitable victimisation that defines her narrative. The incredibly versatile Gareth Yuen shines not only as the poet Pan, but also in two smaller roles Ng and Song, unforgettable with his impeccable timing, and a meticulously calibrated physicality that draws us deep into the nuances of everything he wishes to say. It is a fantastic cast of eight, each performer contributing passion and diligence, in what feels like an unprecedented production about Asian-Australian identities.

Through a story about early Chinese settlers, we are invited to contemplate both the contributions of minority communities on this land, as well as our rarely interrogated complicity in colonialism. The dispossession of Indigenous peoples is our greatest sin, one that non-Indigenous people of colour have yet to sufficiently own up to. In The Poison of Polygamy we observe also the disturbing congruence between Asian and white values, especially in terms of how we regard money. We may be able to celebrate what might be thought of as an Asian proclivity for sharing and for society building, but there is no denying our tendencies for exploitation and pillage. Wrongdoers in the play eventually meet their punishment, but the ending is far from happy ever after. There is a lesson to be learned about how we rectify mistakes, not only of our own but also of our forebears, and one suspects a major paradigm shift is in order.

www.sydneytheatre.com.au | www.laboite.com.au