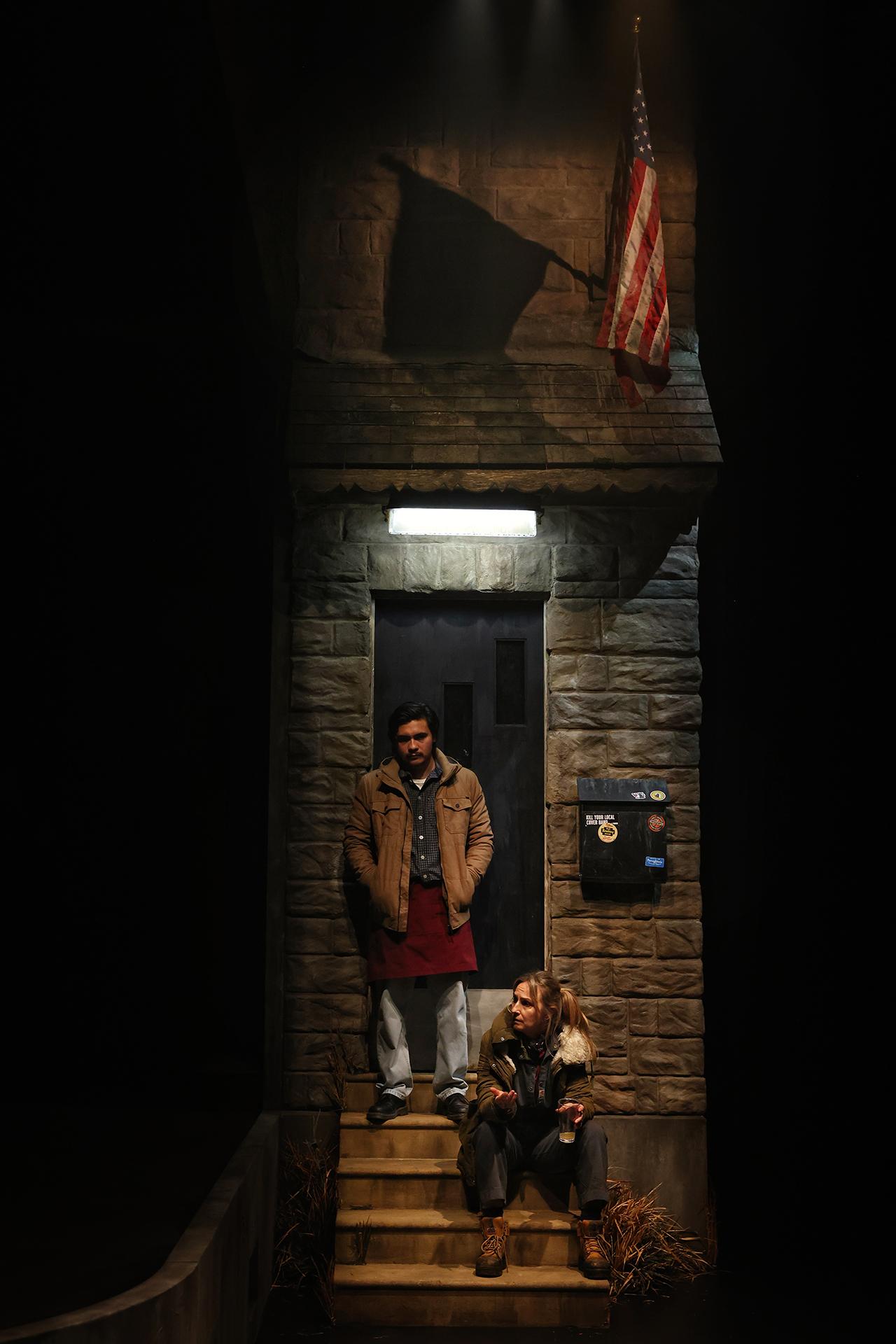

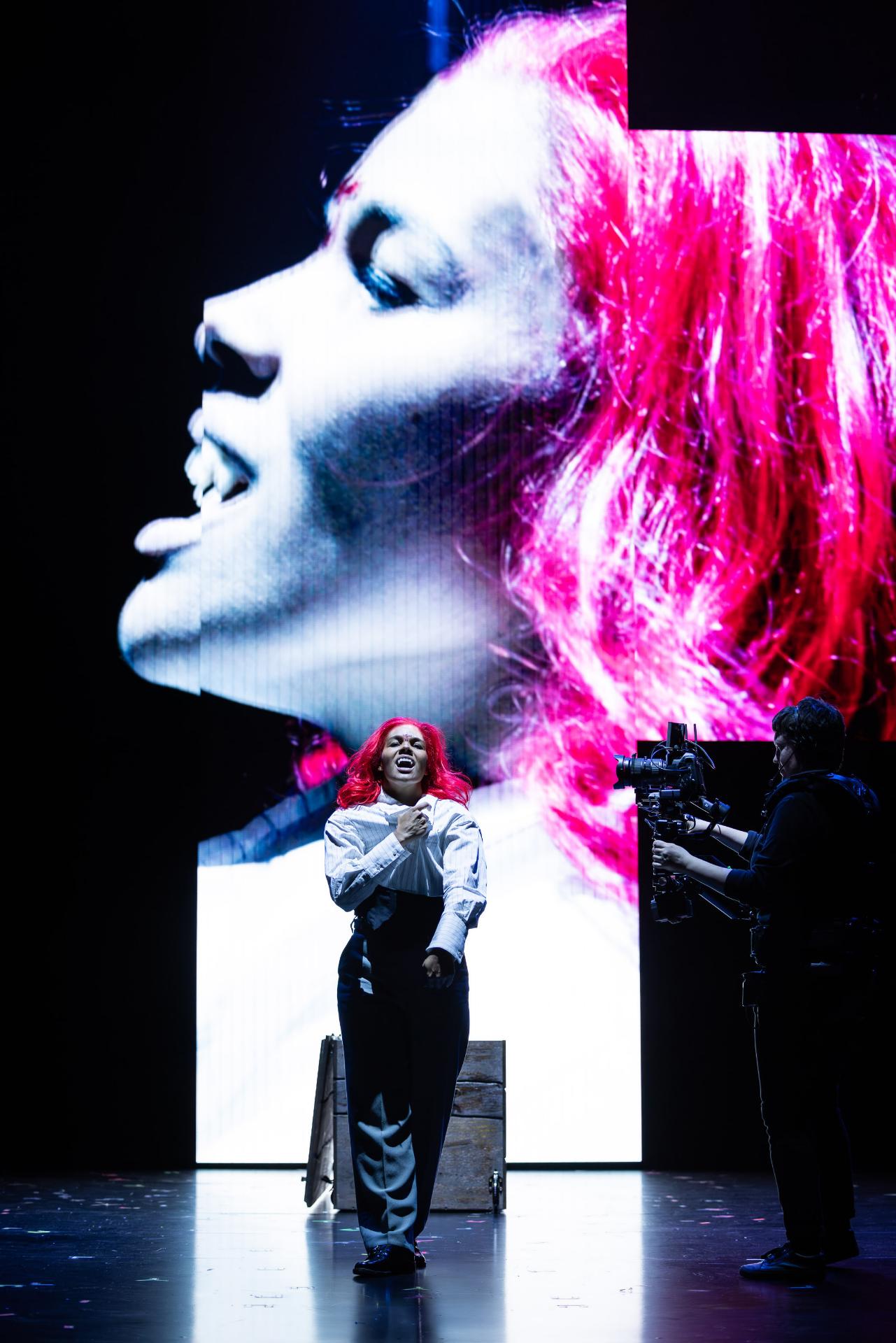

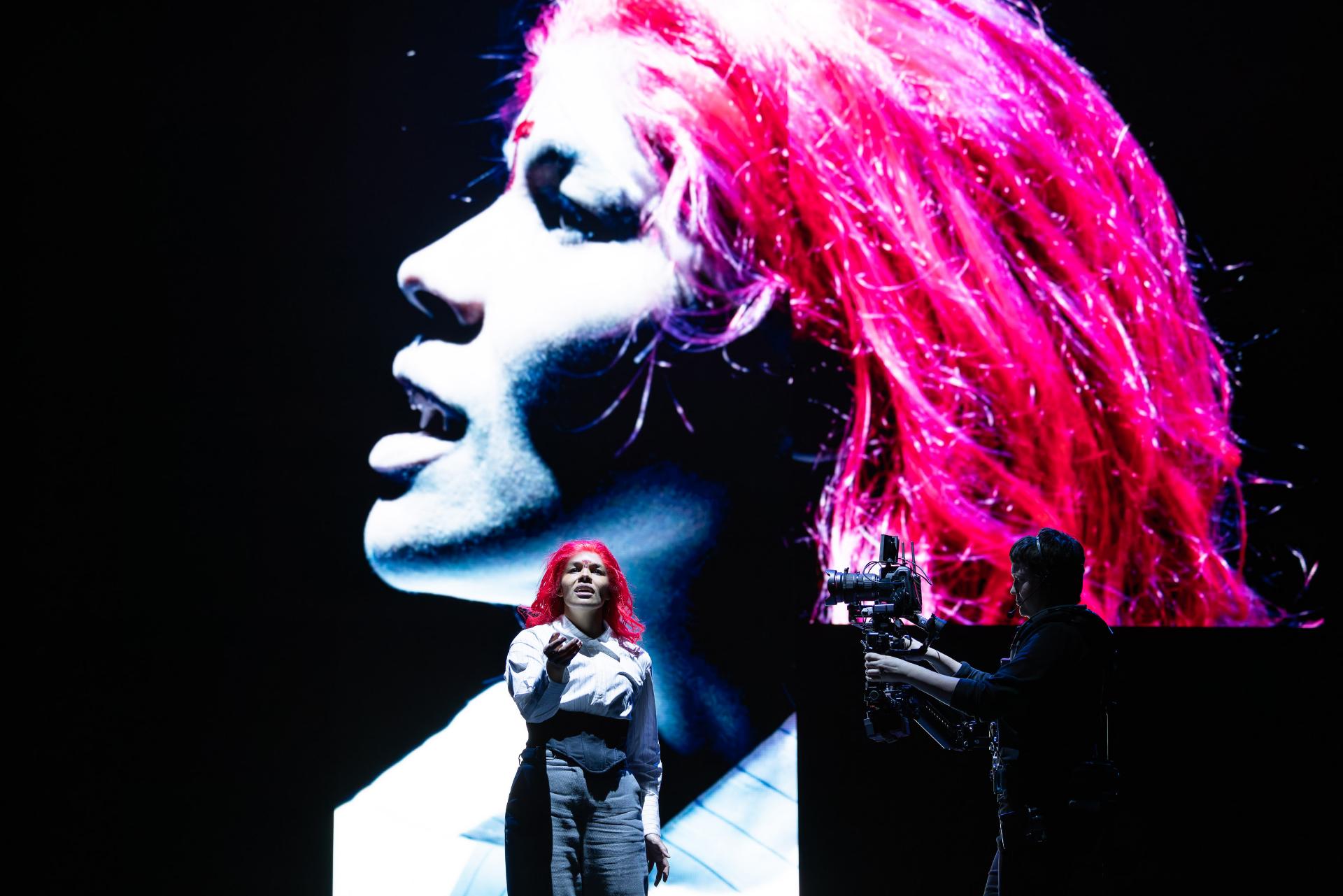

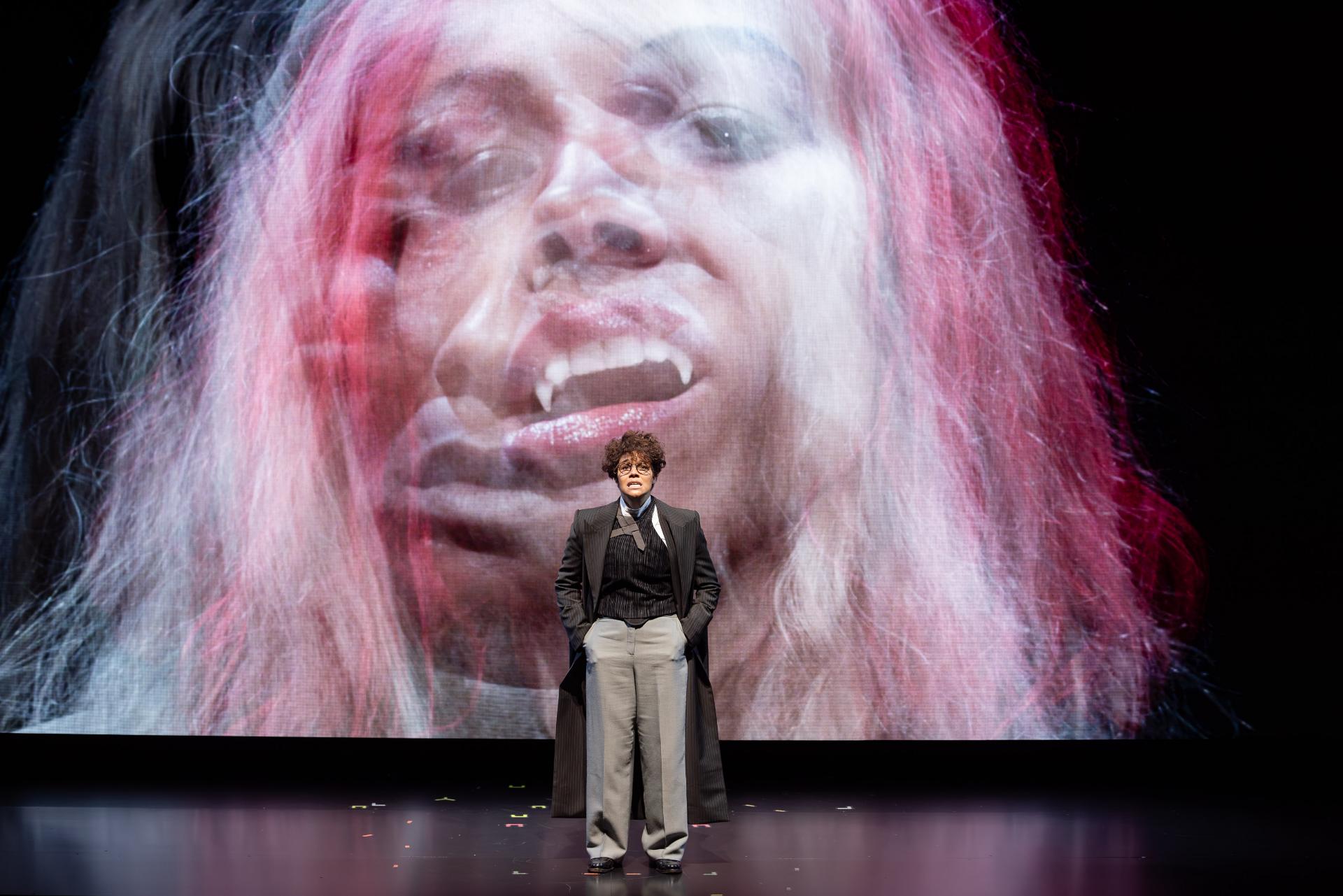

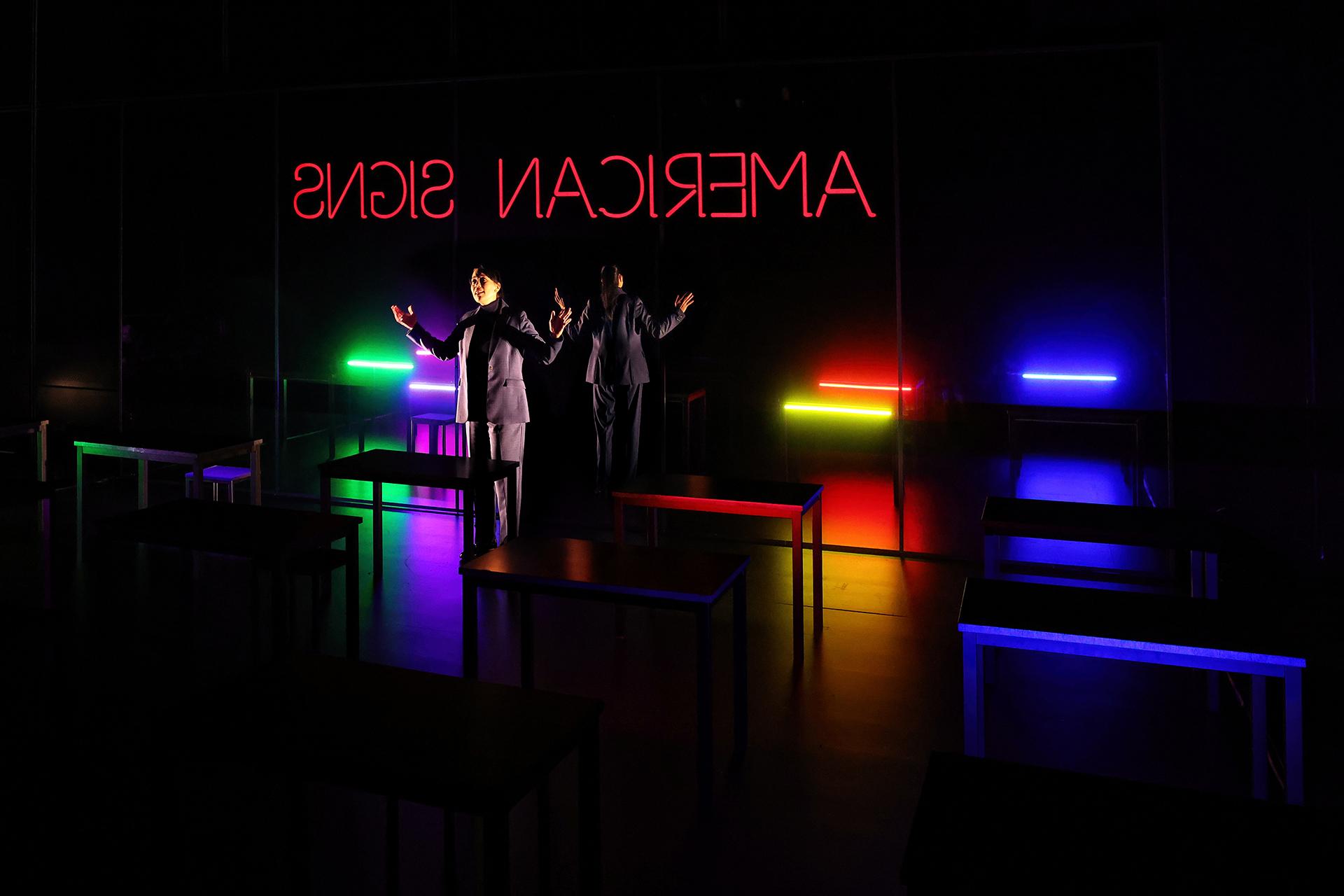

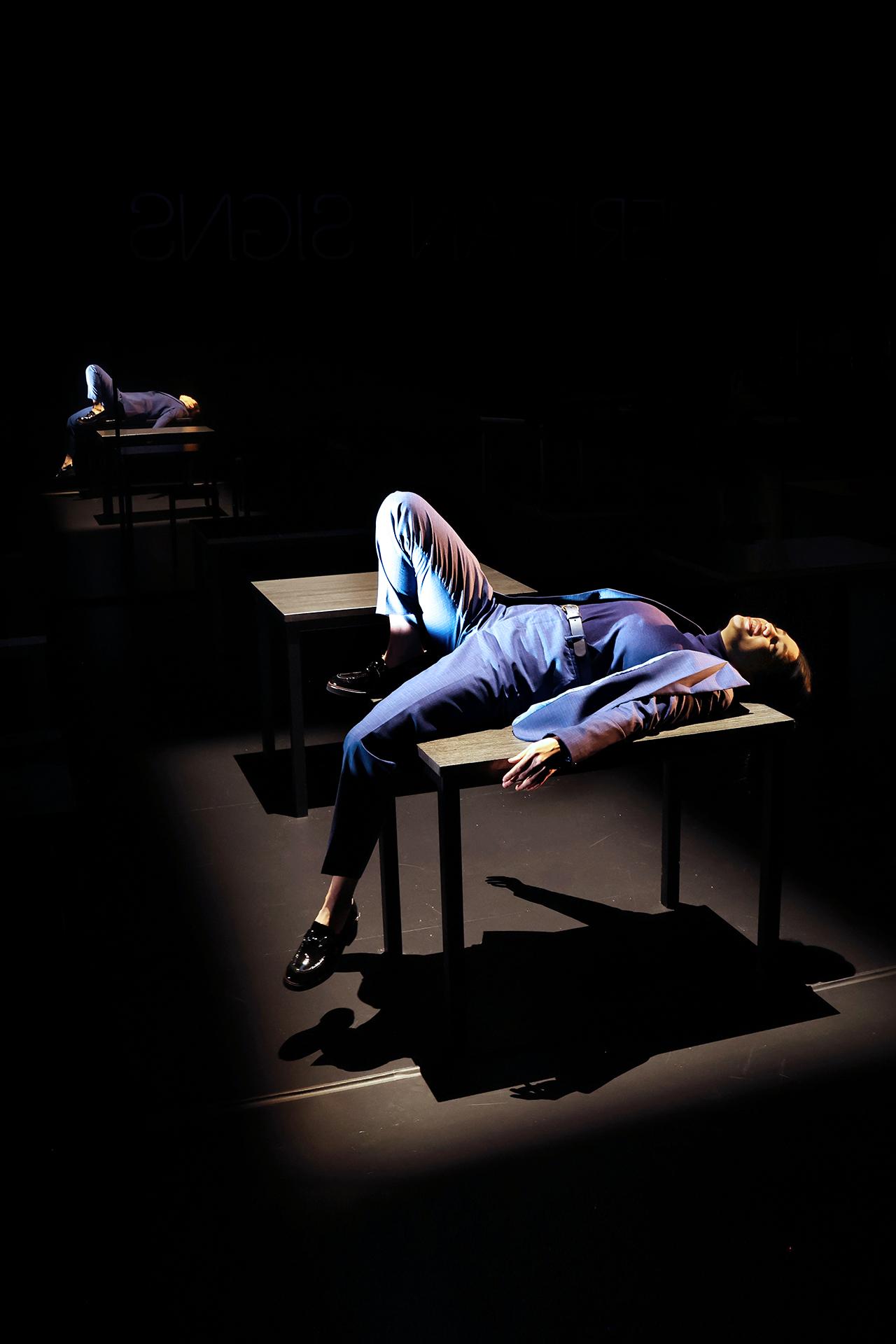

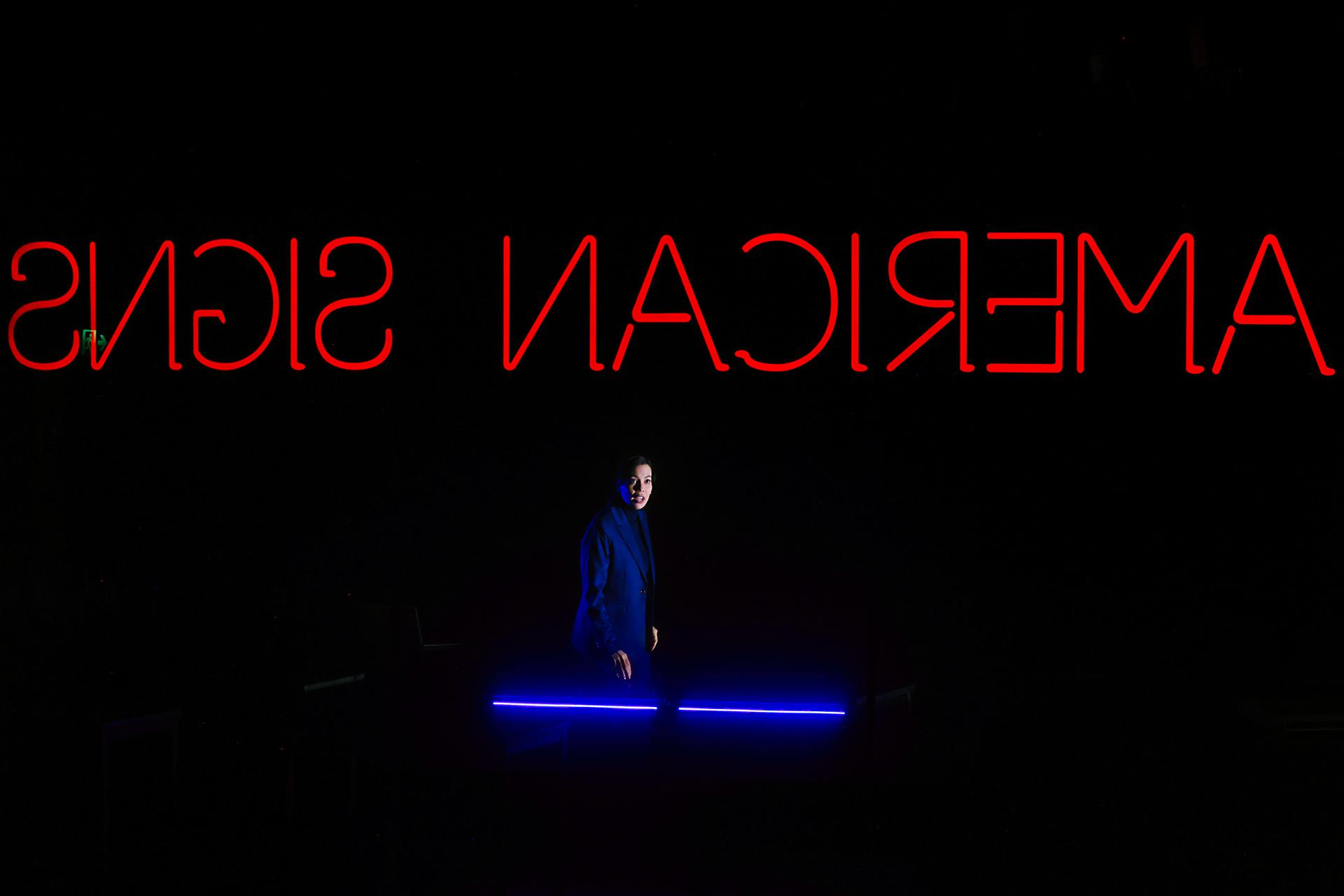

Venue: Wharf 1 Sydney Theatre Company (Walsh Bay NSW), 8 Feb – 23 Mar, 2025

Playwright: Amy Herzog

Director: Kenneth Moraleda

Cast: Nancye Hayes, Shiv Palekar, Ariadne Sgouros, Shirong Wu

Images by Daniel Boud

Theatre review

Leo had only intended to drop in at his grandmother Vera’s for a quick visit, but ends up staying for much longer. Amy Herzog’s 4000 Miles is about kinship, and the human need for connection at a time when we are increasingly isolated. It is almost strange to see a young and an old person together, even though they are family, and should appear completely natural and matter of course. Such is the extent of our alienation in this day and age.

It is a humorous piece of writing by Herzog, remarkable for the delicate rendering of its characters’ frailties along with the intimate refuge they find in each other. Direction by Kenneth Moraleda is strikingly tender, full of sensitivity and genuine poignancy, for a show that speaks volumes about what we should regard to be the most important in life. It is never a saccharine experience, but always quietly profound, and subtly persuasive.

Production design by Jeremy Allen delivers a realism that helps make the storytelling seem effortless. Kelsey Lee’s lights bring immense warmth, with occasional punctuations of visual poeticism that feel transcendent. Music compositions by Jess Dunn are wonderfully pensive, with a rich sense of yearning to inspire further emotional investment in something truly universal.

Actor Nancye Hayes captivates with the charm she imbues Vera, but it is the honesty she is able to convey that really impresses. The eminently watchable Shiv Palekar as Leo too is resonantly truthful, in his depictions of someone finding his way out of trauma. The exquisite chemistry between the two is quite a thing to behold, and can be credited as the main element behind the production’s success. Also memorable is performer Shirong Wu as Amanda, utterly hilarious in her one unforgettable scene. Leo’s girlfriend Bec is played by Ariadne Sgouros, adding dimension to our understanding of dynamics between characters in 4000 Miles.

Vera’s friends are all leaving this plain, one at a time. In her twilight moments, she finds herself becoming an essential source of support for her grandson, and in this discovery of new meaning, we observe a new lease of life, for both Vera and Leo. In their care of one another, each is required to bring out the best of themselves. Modernity seems intent on drawing attention to many of our worst sides, but it seems that when we tend only to things that matter, a clarity emerges to help us decipher what is good.