Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Sep 27 – Nov 1 2025

Book, Music & Lyrics: Jonathan Larson

Director: Shaun Rennie

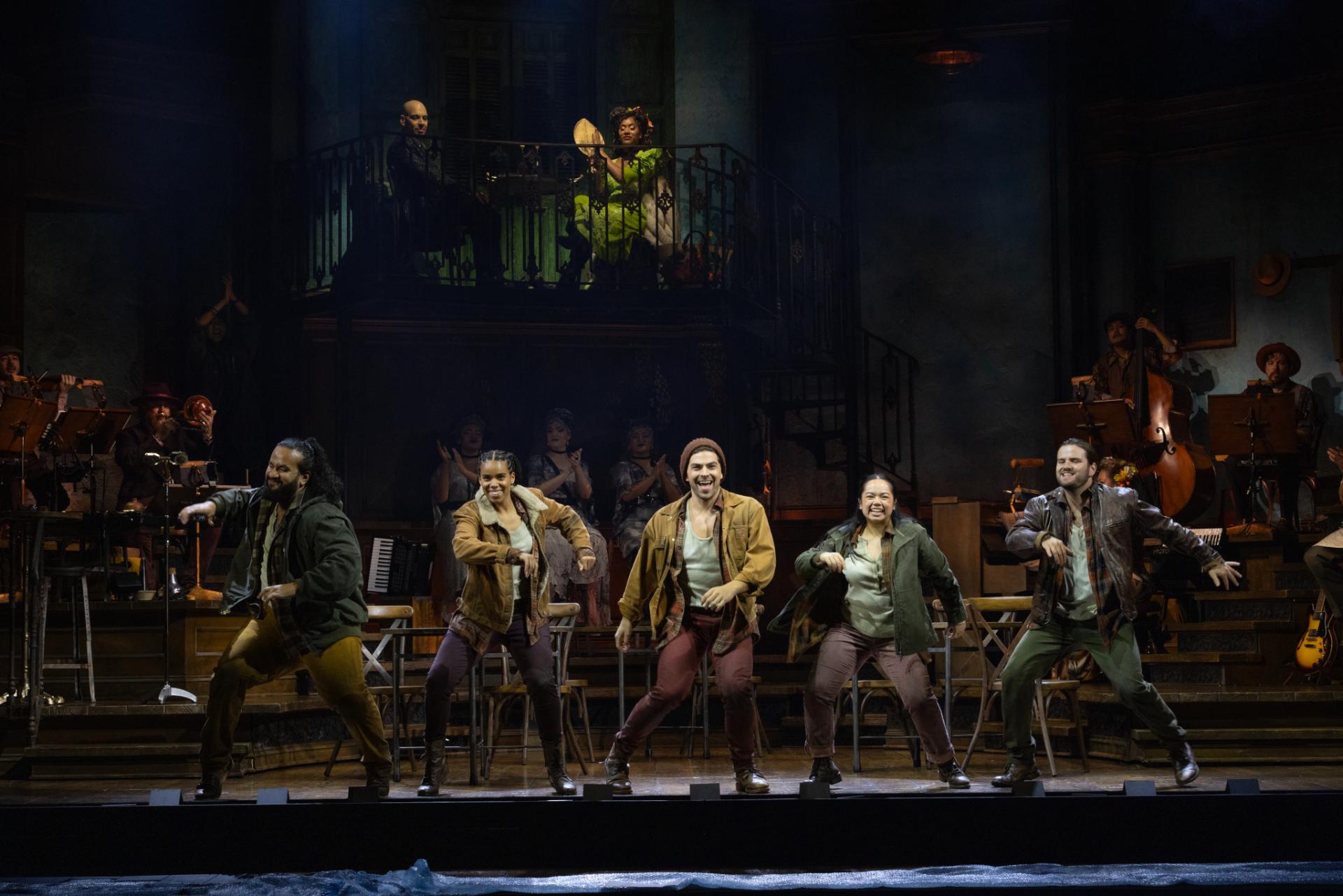

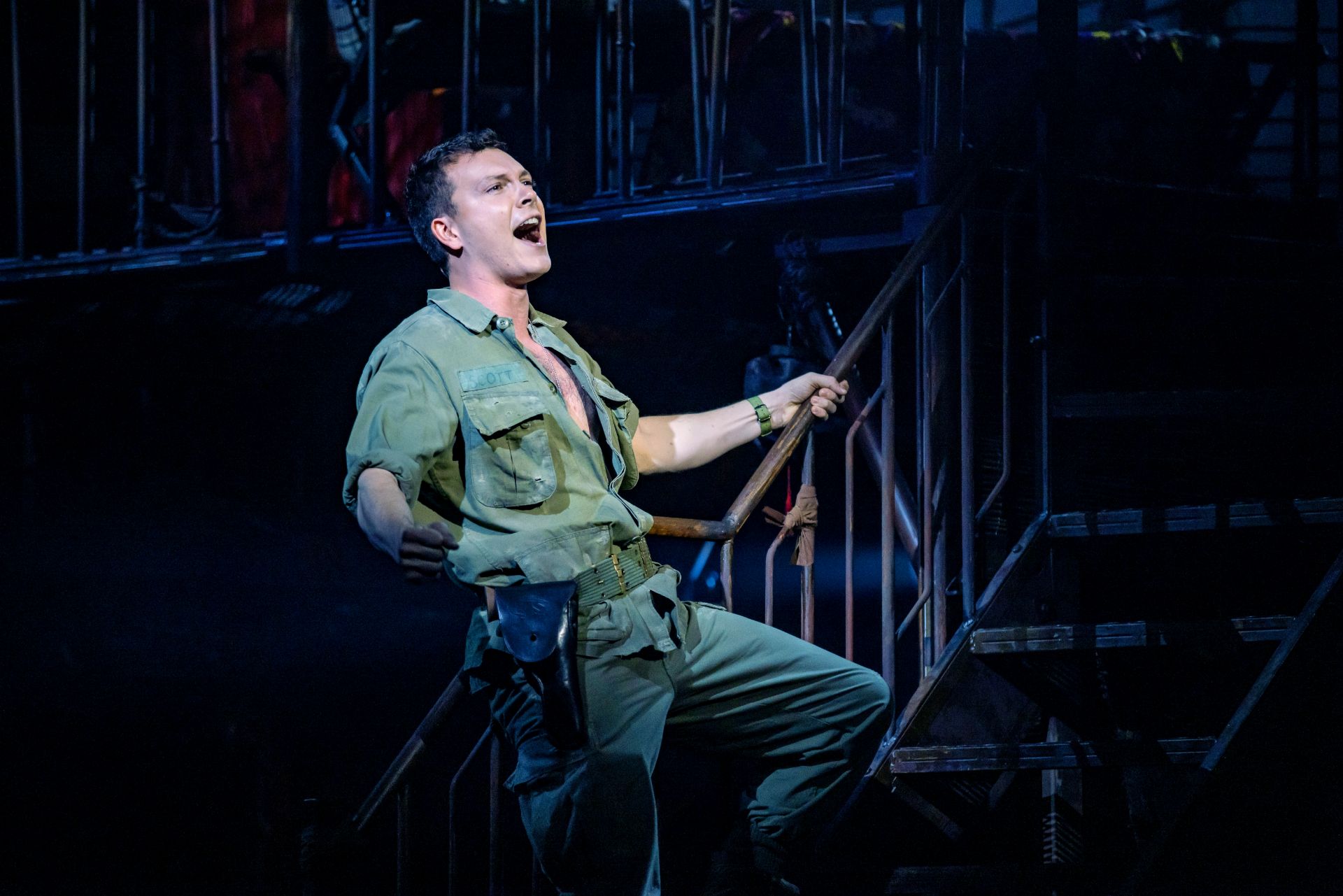

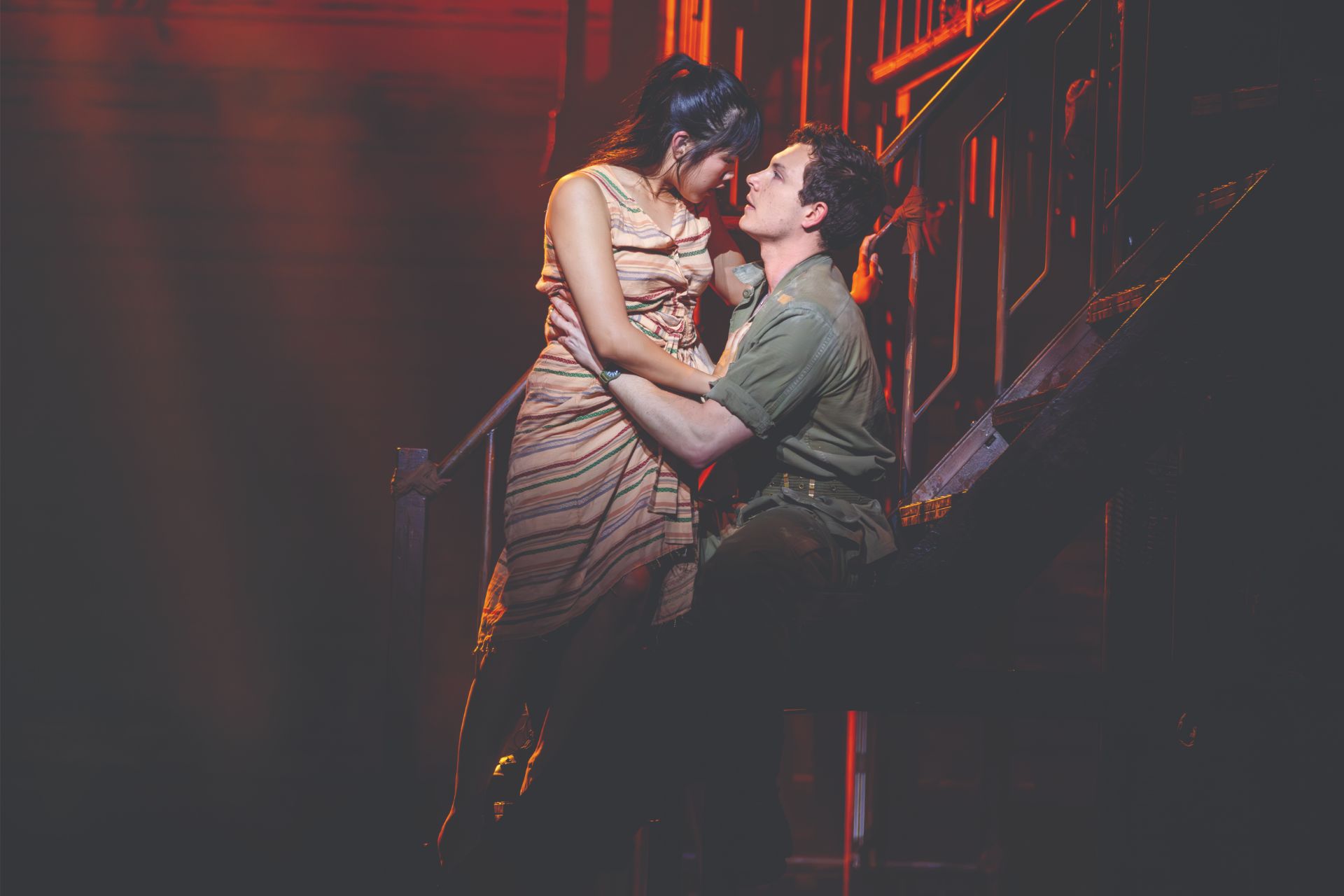

Cast: Jesse Dutlow, Googoorewon Knox, Tana Laga’aia, Calista Nelmes, Kristin Paulse, Henry Rollo, Harry Targett, Imani Williams

Images by Pia Johnson, Neil Bennett

Theatre review

When Jonathan Larson completed his magnum opus Rent in 1996, he could not have foreseen that the bohemian enclave of New York City he celebrated was already in its twilight. Within a year, Rudy Giuliani’s iron-fisted mayorship would begin reshaping the city, erasing the fragile counterculture that had given Rent its heartbeat. Nearly three decades on, some of its echoes have softened, but the core refrain remains. The story of an underclass ignored by a complacent American mainstream feels newly pertinent in an era marked by authoritarian politics and cultural division.

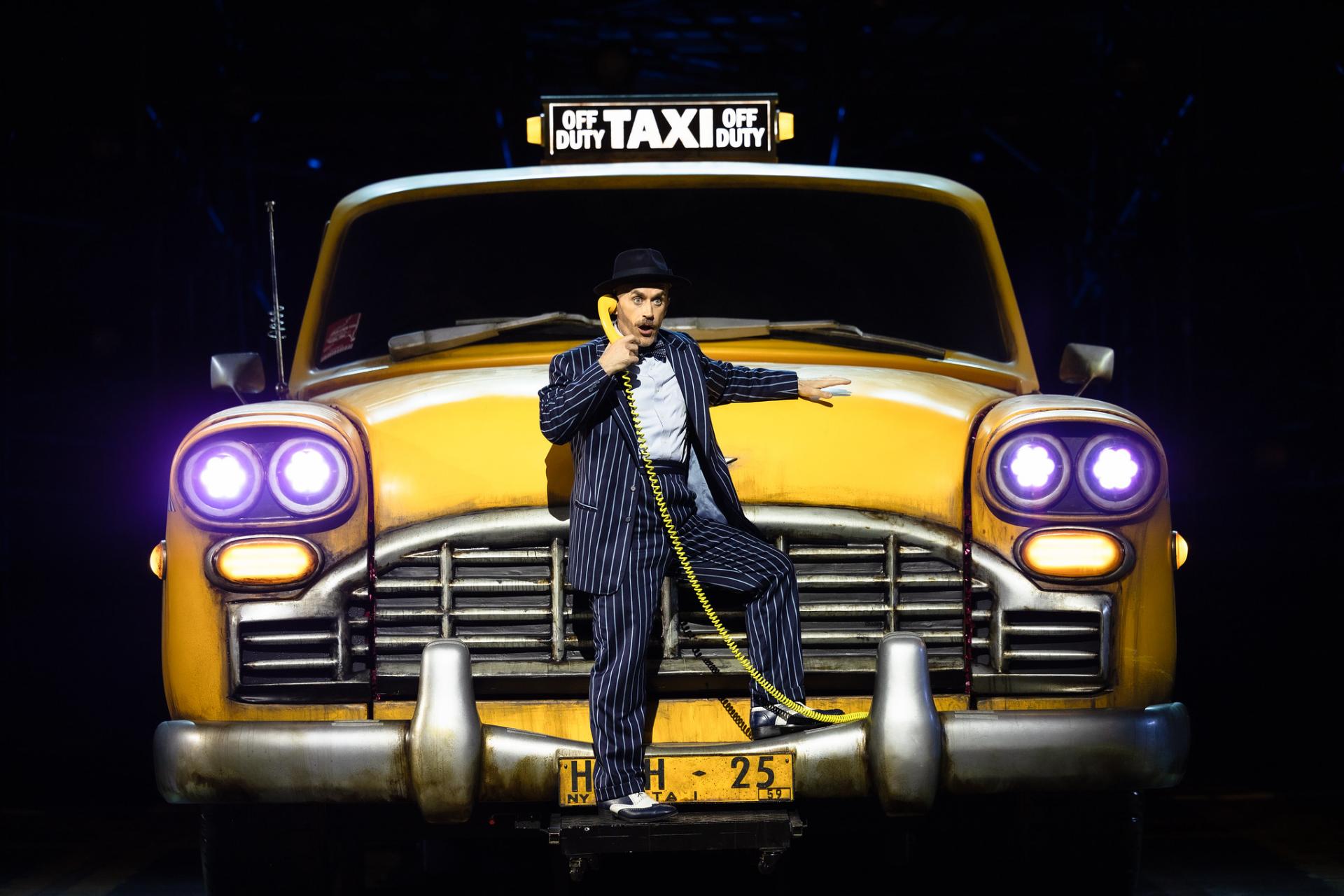

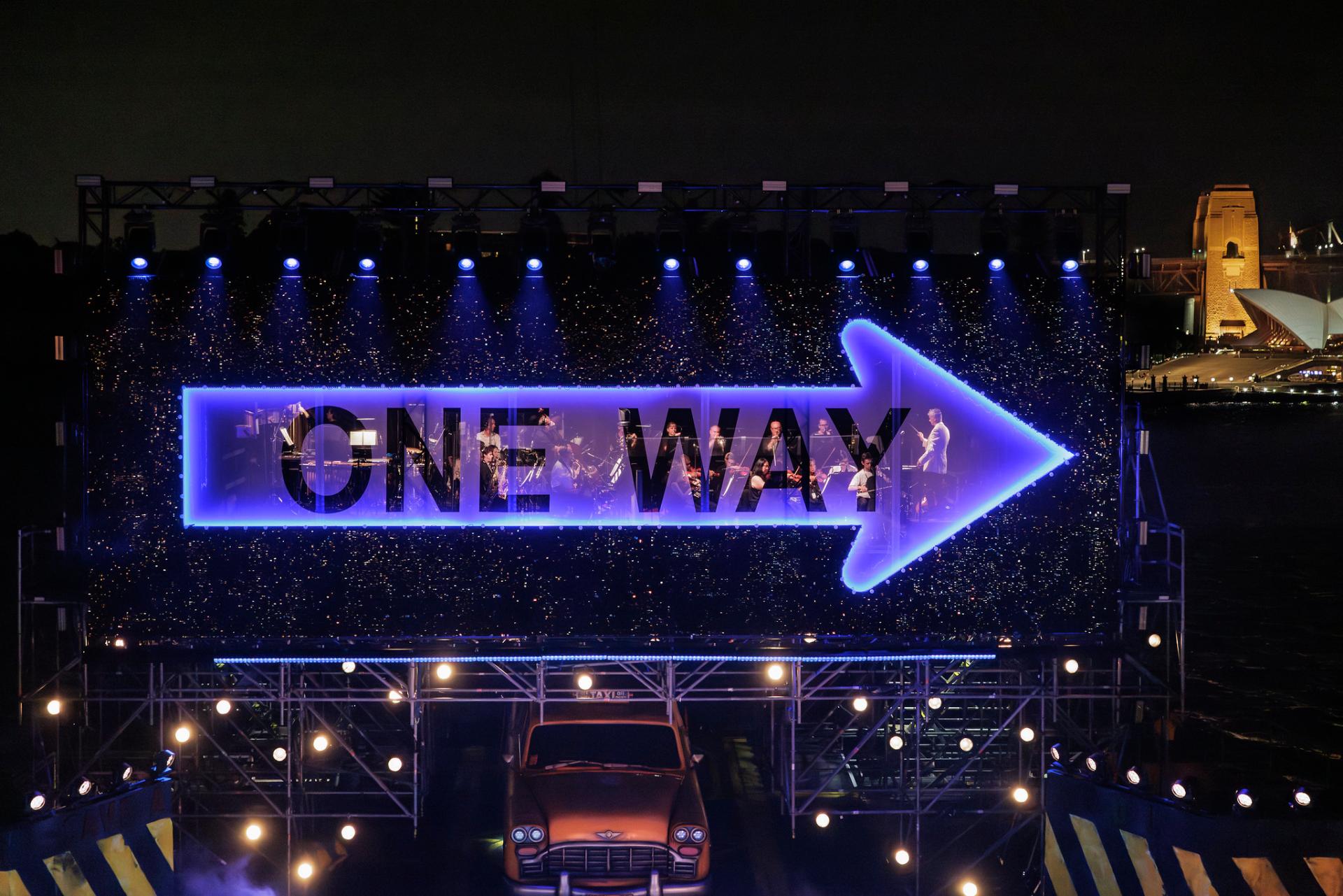

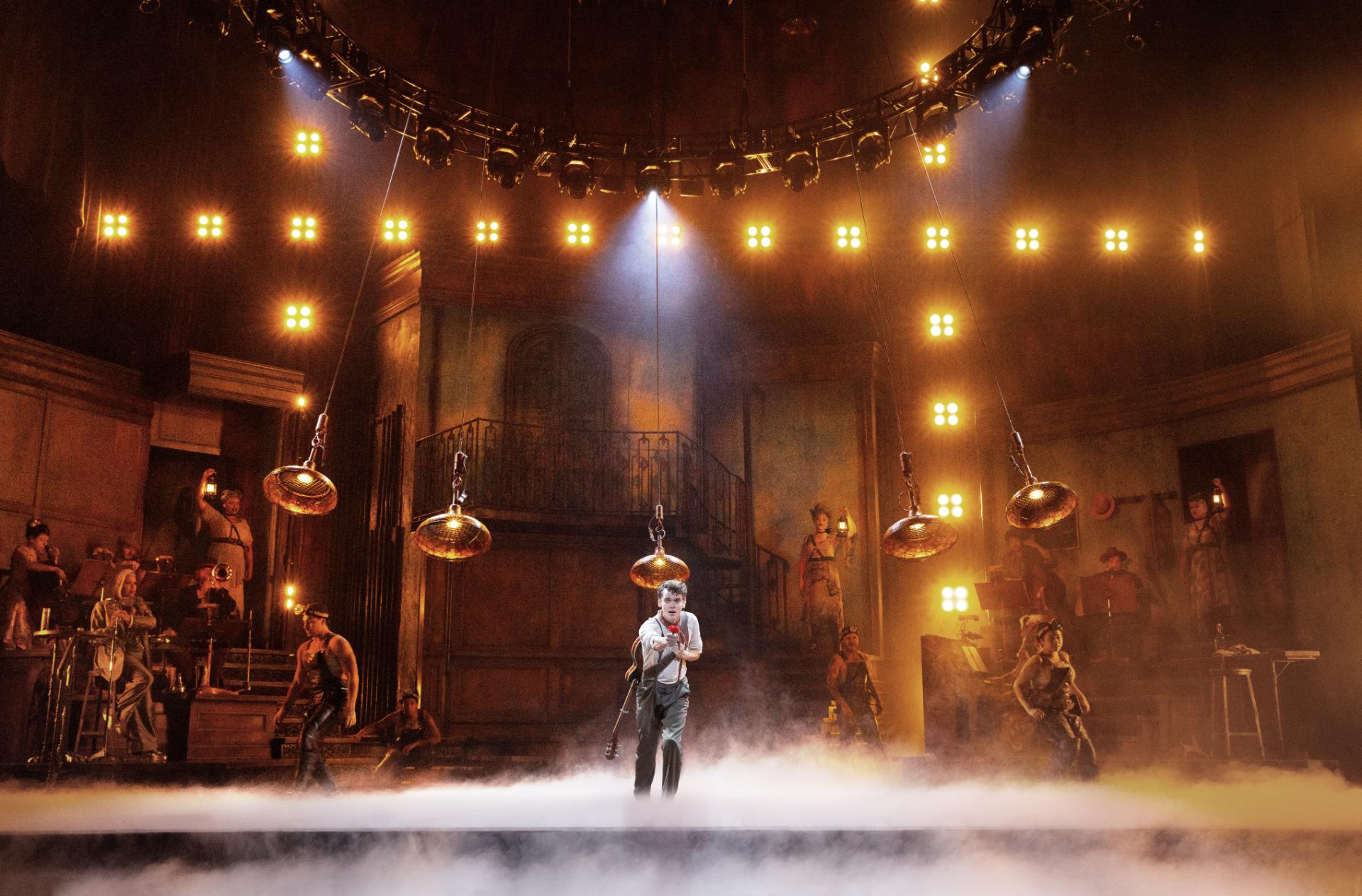

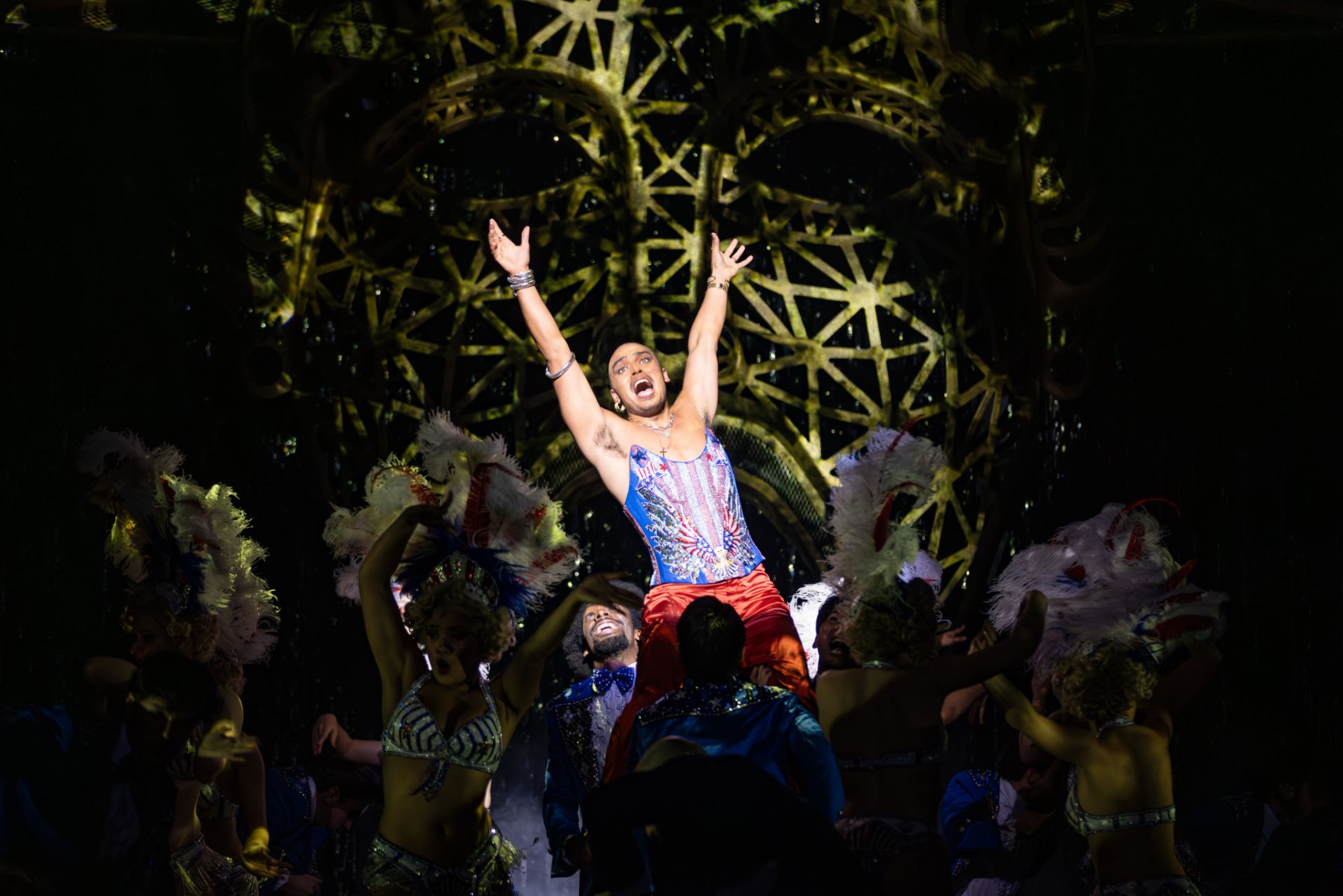

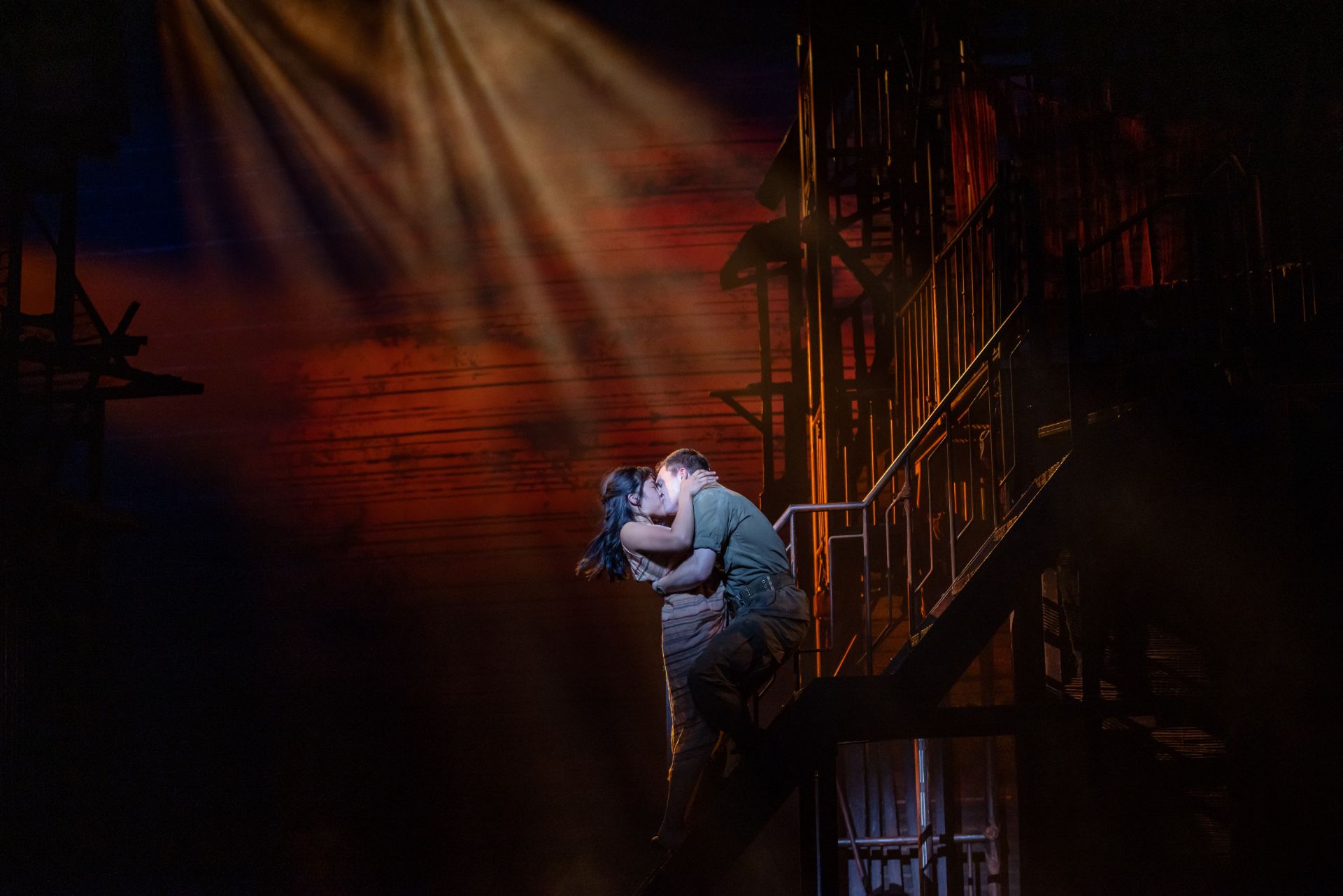

Whether Larson’s writing truly earns its lofty reputation is open to debate, but Shaun Rennie’s direction in this revival is beyond question. His staging shimmers with a visual splendour that conjures spectacle without betraying the grit of a neighbourhood on the margins. What once risked sounding trite in Rent is here imbued with unexpected sincerity, the familiar refrains lifted into something that feels palpably meaningful.

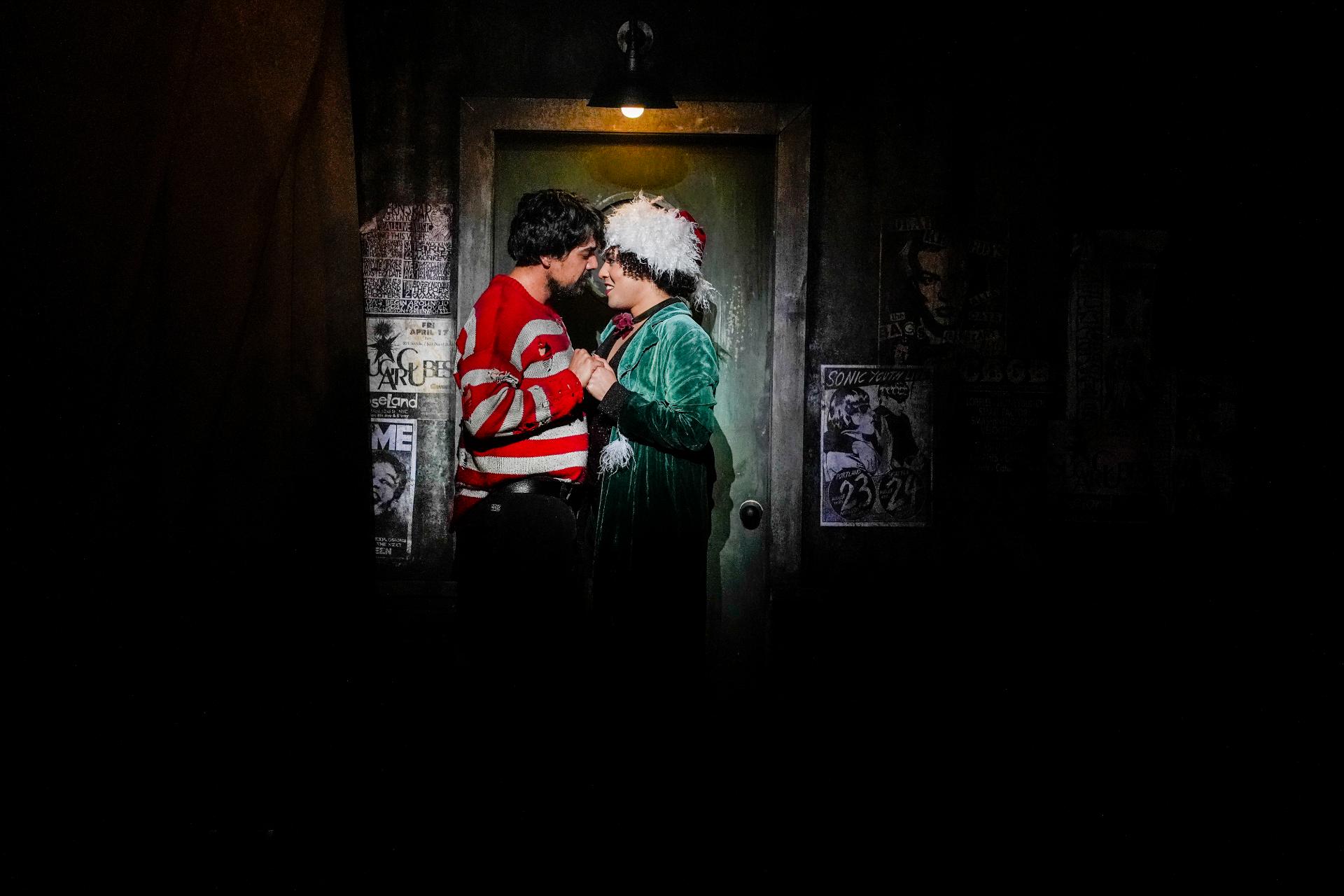

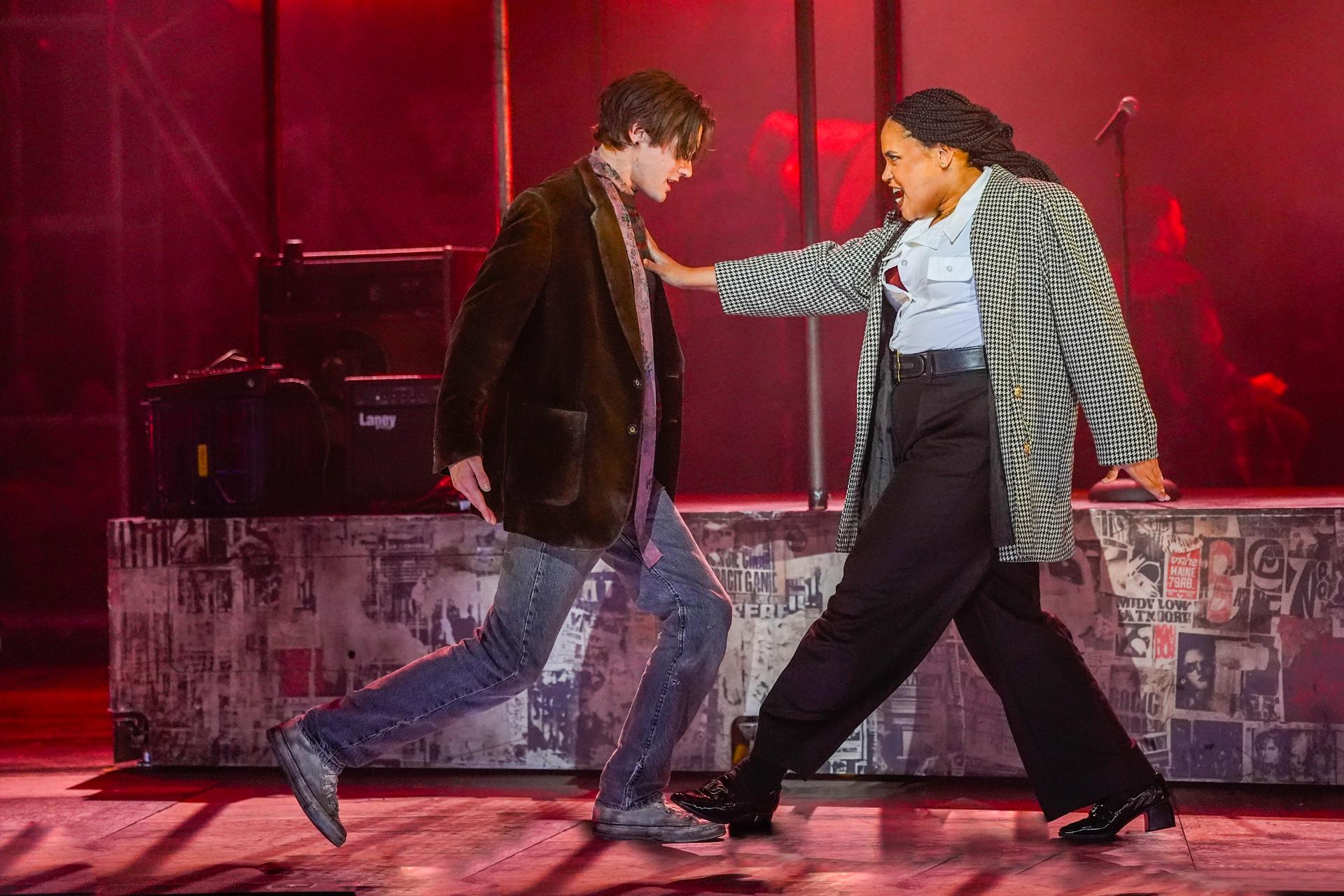

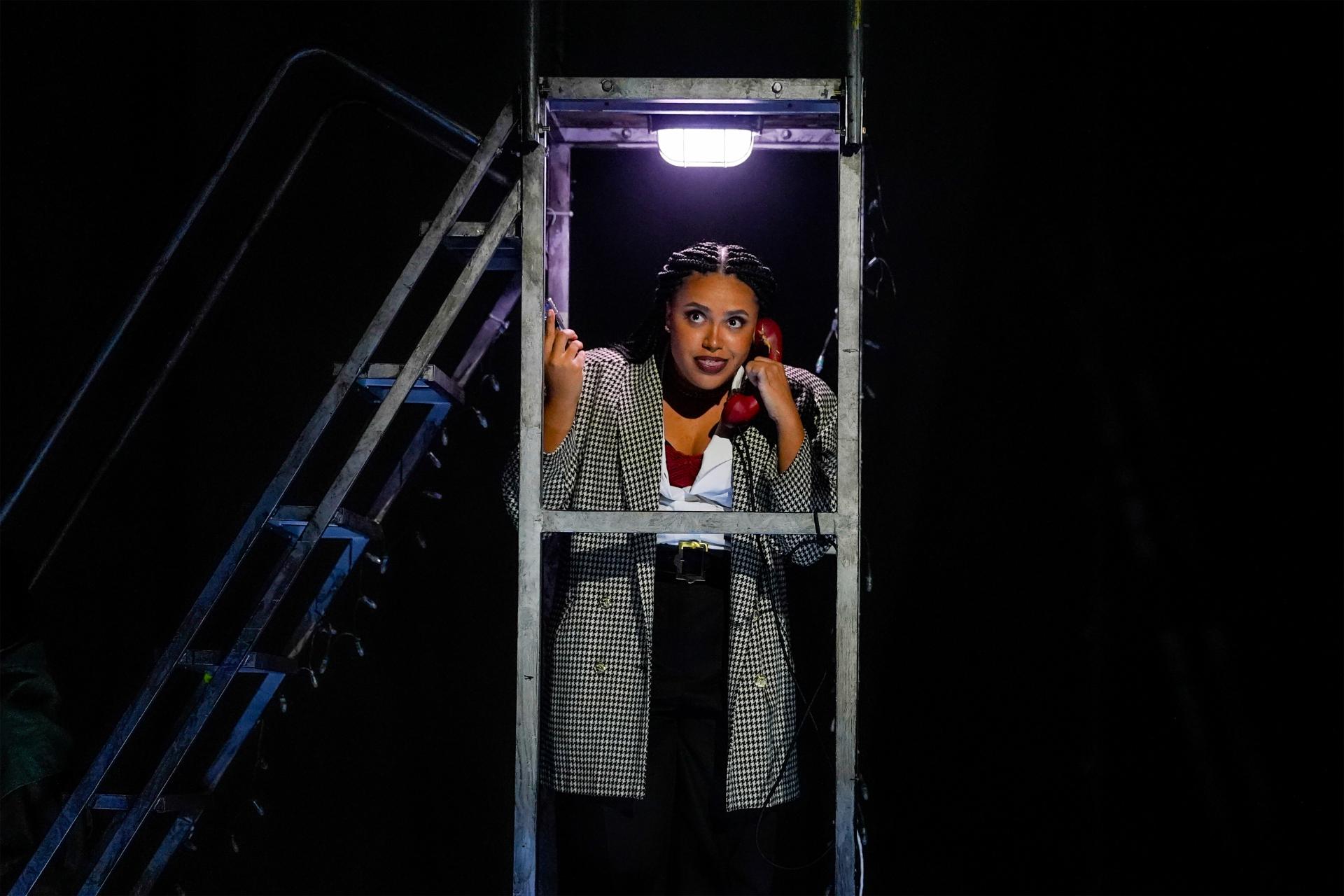

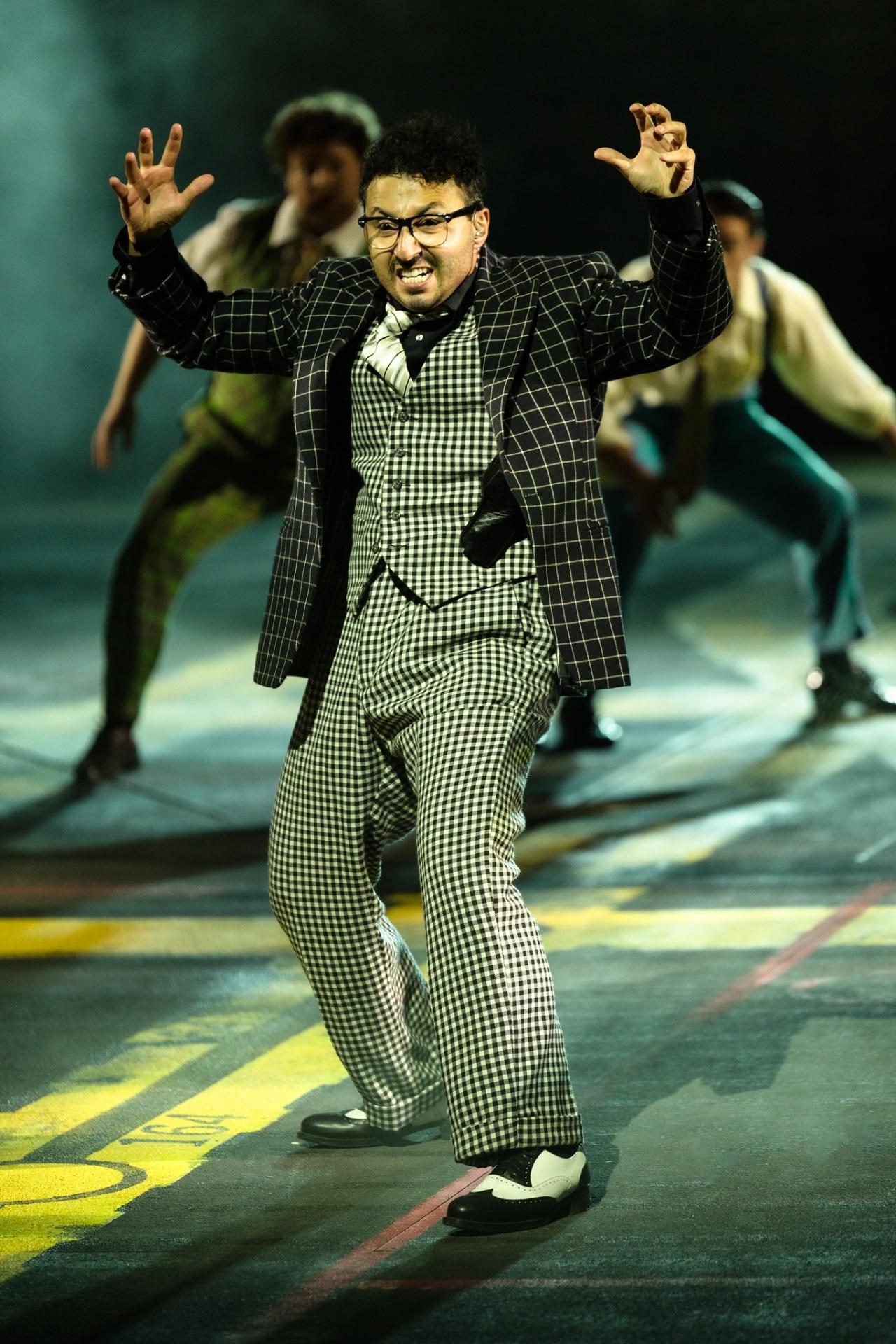

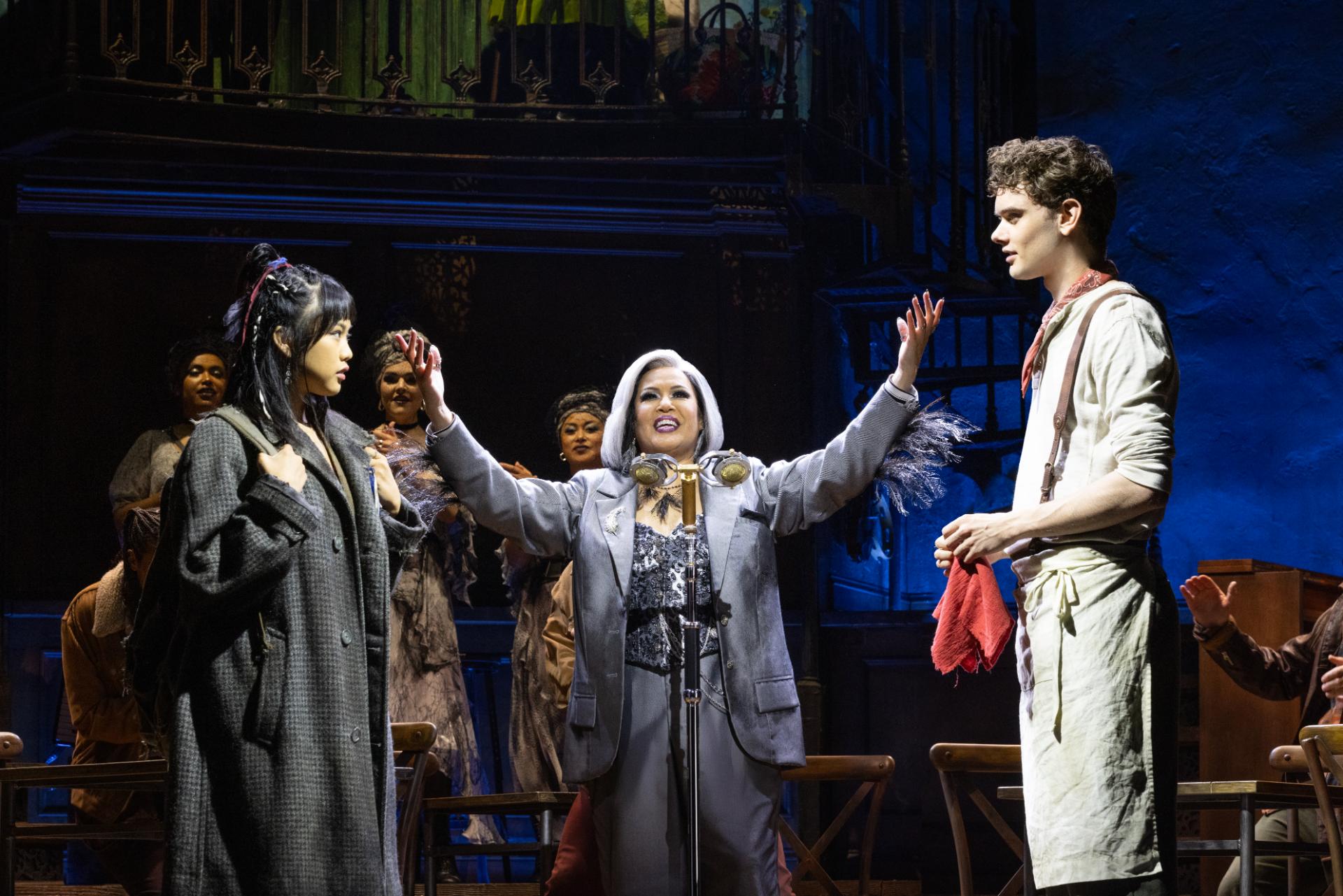

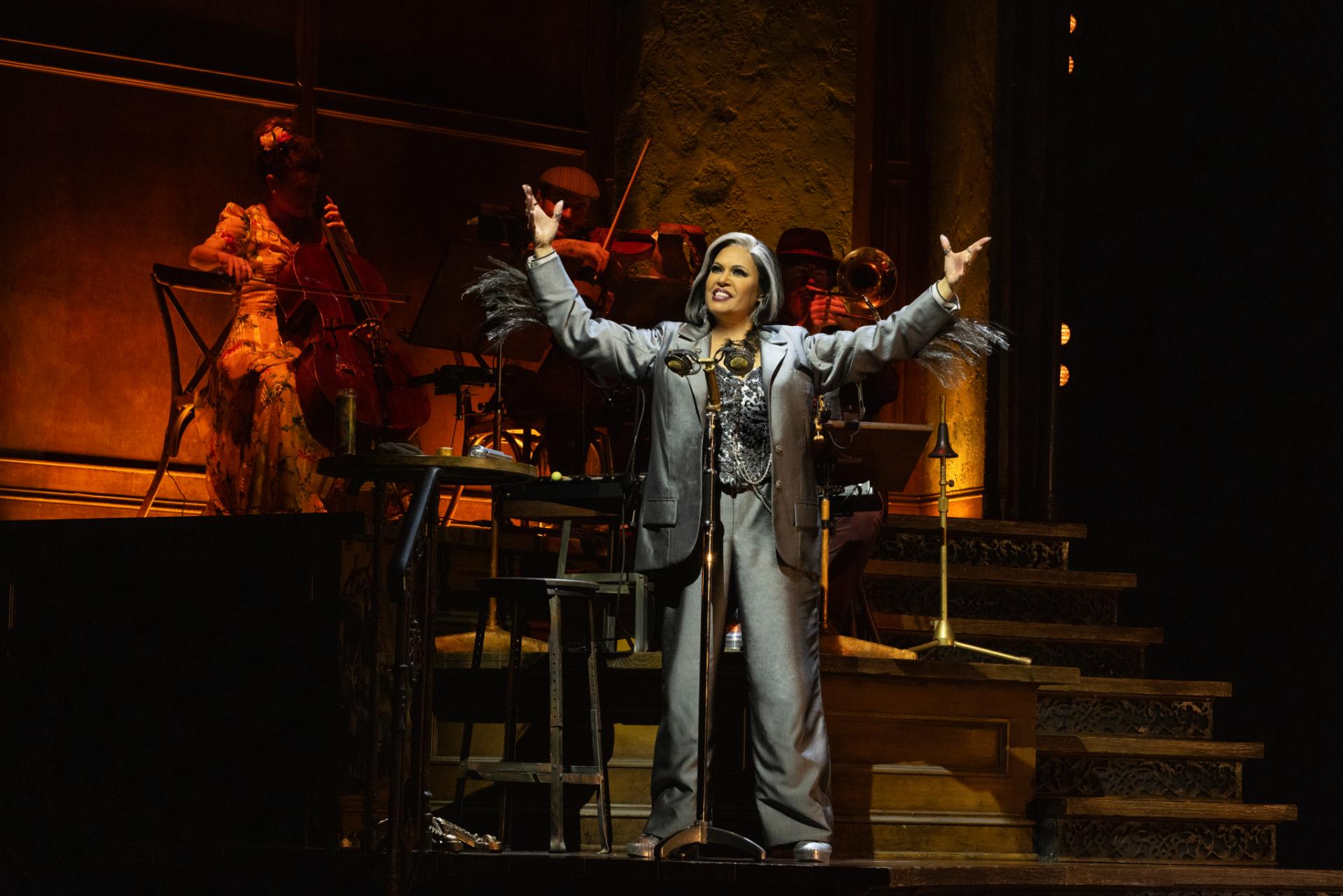

Dann Barber’s set design astonishes in its detail and completeness, evoking both the era and the grunge locale with unflinching accuracy, while offering theatricality that never ceases to enthral the eye. Ella Butler’s costumes bring striking authenticity to a multitude of characters, yet always sustain a visual harmony across the stage. Paul Jackson’s lighting is profoundly evocative, conjuring memory and emotion in equal measure, and captivating us with an endless stream of potent imagery.

The cast is uniformly endearing, each performer delivering not only exceptional vocal power but also a sincerity that grounds the musical’s sweeping emotions. Calista Nelmes all but stops the show with her riotous, electric turn as Maureen in “Over the Moon,” while Harry Targett imbues Roger with an actorly intensity that lends the production its beating heart. Equally praiseworthy are Luca Dinardo’s choreography and Jack Earle’s musical direction—both infused with passion and executed with polish, their work bold in vision and shimmering with invention, breathing new vitality into a show that has long lived in the cultural imagination.

Perhaps the most crucial truth that Rent represents is that, in much of American culture and tradition, those at the bottom rungs are deemed undesirable—or even expendable. The AIDS crisis laid bare the ease with which Americans could turn on one another, exploiting capitalist values or religious fervour as justification for prejudice and cruelty. Today, the same currents ripple through a new era of fascism, as communities are singled out, scapegoated, offered up as sacrificial lambs to feed the hunger for false promises and hollow triumphs. The musical’s story, though decades old, pulses with uncanny relevance, a mirror to a society still grappling with whom it chooses to value and whom it casts aside.

Venue: Riverside Theatres (Parramatta NSW), Jan 15 – Feb 1, 2020

Venue: Riverside Theatres (Parramatta NSW), Jan 15 – Feb 1, 2020

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), from Aug 16 – Oct 6, 2019

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), from Aug 16 – Oct 6, 2019