Venue: Wharf 1 Sydney Theatre Company (Walsh Bay NSW), Jan 8 – 25, 2025

Composer: Luke Di Somma

Libretto: Luke Di Somma, Constantine Costi

Director: Constantine Costi

Cast: Christopher Tonkin, Kanen Breen, Cathy-Di Zhang, Simon Lobelson, Louis Hurley, Danielle Bavli, Russell Harcourt, Thomas Remali, Kirby Myers

Images by

Theatre review

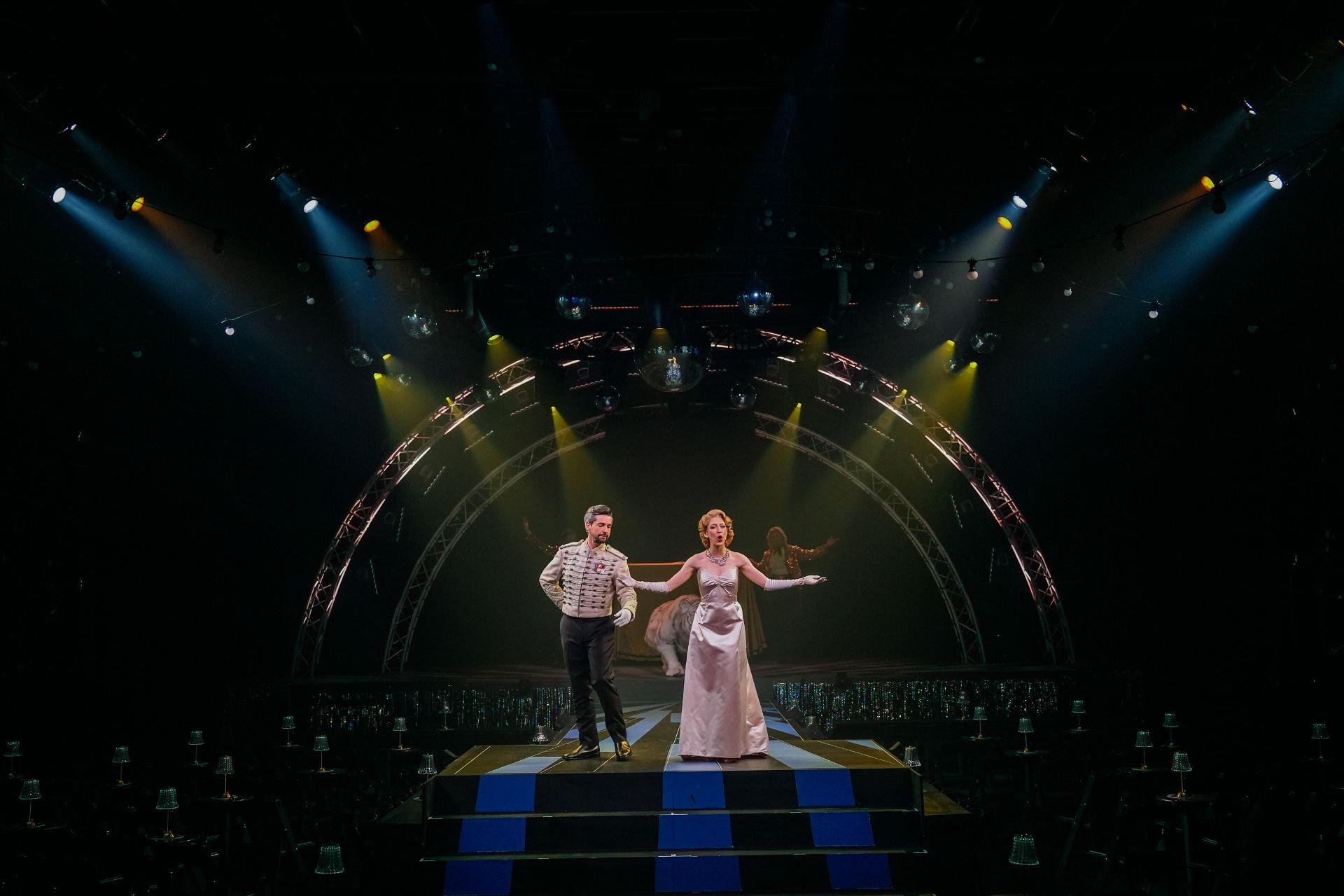

Siegfried & Roy: The Unauthorised Opera by Luke Di Somma and Constantine Costi chronicles, with both reverence and sardonicism, the life and times of the infamous Las Vegas stalwarts from Bavaria. Icons of magic and of queer culture, Siegfried & Roy have left an indelible mark with almost half a century in showbusiness. Their signature aesthetic, characterised by unmitigated flamboyance and camp, thoroughly inform Di Somma and Costi’s work, that we discover to be a sincere tribute to the trailblazers, albeit replete with comedic irony.

Directed by Costi, the show is a remarkably enjoyable look into the condensed history of the couple, not only as stars of entertainment, but also as covert figureheads of gay identities from a time before liberation. There is a wonderful tenderness to the portrayal of the pair, with performers Christopher Tonkin and Kanen Breen (as Siegfried and Roy respectively), delivering palpable chemistry alongside their individually brilliant interpretations of these enigmatic characters. We perceive the superficiality that is characteristic of these pop luminaries, but also feel invested in their humanity without requiring the storytelling to delve into exploitative renderings of their biography.

Set design by Pip Runciman provide just enough visual cues for imagery that recalls the excess of both Las Vegas and of Siegfried & Roy, but it is Damien Cooper’s lights that imbue a sense of opulence that transports us to that space of farcical extravagance. Costumes by Tim Chappel too are appropriately outlandish in style, with an unmistakeable wit that really makes an impression. All of this grandiosity is perhaps most effectively epitomised in the music, conducted by Di Somma to bring an immense spiritedness that has us absolutely riveted.

Siegfried & Roy never wanted to give us more than the surface, but it is the persistence and the longevity of that obsession with artificiality, that ultimately forms something paradoxically meaningful. They have become unwitting symbols of kitsch, of escapism, of dedication and of defiance. Their story is one of personal triumph, a rare example of queer forebears attaining stratospheric success with seemingly little compromise on authenticity. Perhaps their legacy can now contribute to their rainbow community, in ways they were unable during the cruelly oppressive epoch of the previous century.

Venue: Festival Theatre (Adelaide SA), Mar 3 – 9, 2017

Venue: Festival Theatre (Adelaide SA), Mar 3 – 9, 2017