Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Jul 27 – Aug 20, 2022

Playwright: Mike Bartlett

Director: Lucy Clements

Cast: Jane Angharad, Joanna Briant, Claudette Clarke, Alec Ebert, Deborah Jones, Mark Langham, Rhiaan Marquez, Ash Matthew, Charles Mayer, James Smithers, Emma Wright

Images by Clare Hawley

Theatre review

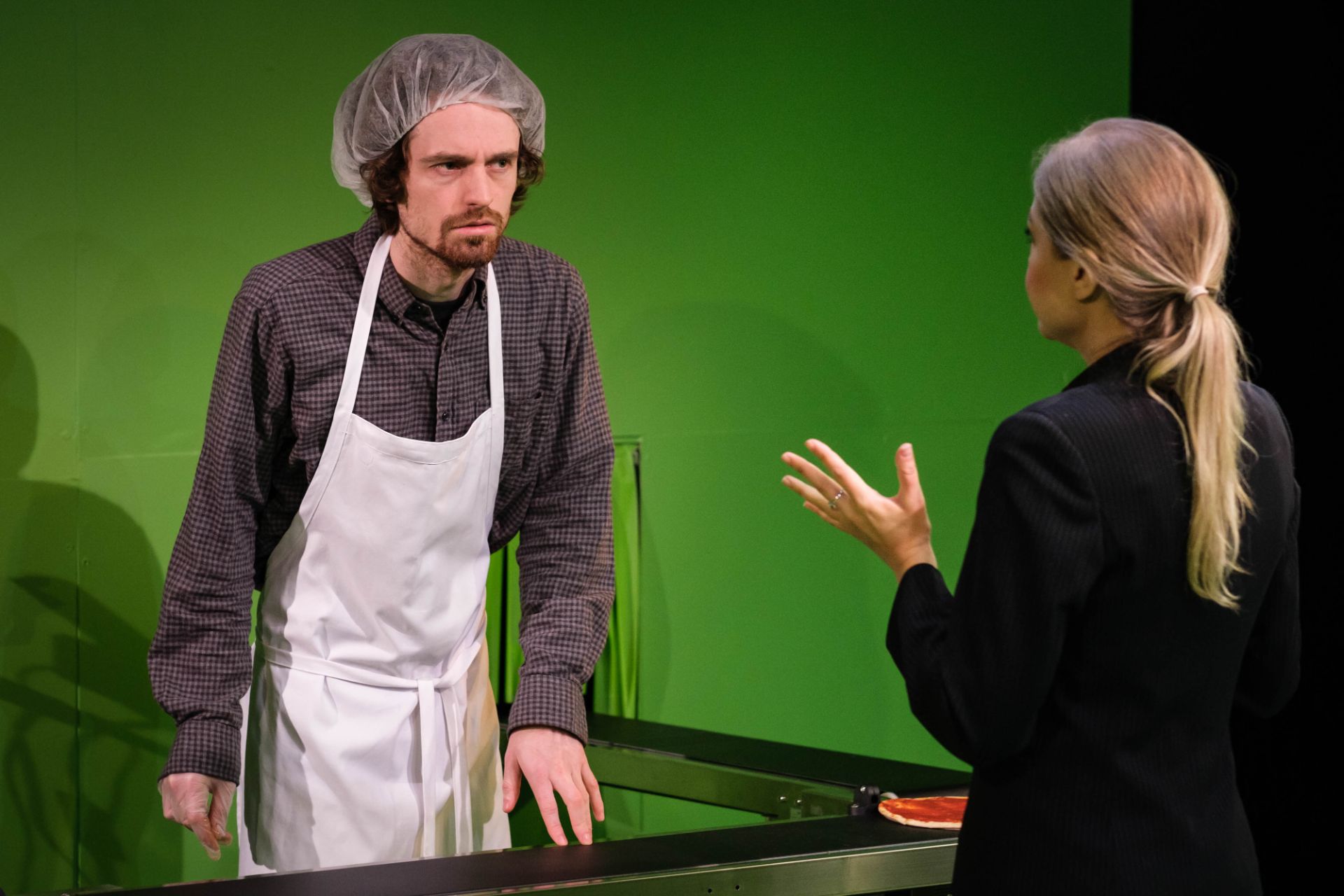

After making a fortune from her retail business, Audrey decides to revive a stately home, located some distance away from her usual London residence. What initially looks to be a noble enterprise, soon reveals itself to be a project that is more problematic, than Audrey had ever imagined. Mike Bartlett’s Albion explores the meanings of conservative values in the twenty-first century. In a literal way, characters play out the repercussions of one rich woman’s desire to preserve a relic. Wishing to hold on to the past, can be thought of as part and parcel of being human, but in Albion it becomes evident that to resist change, is perhaps one of the most extravagant indulgences, that only the privileged can afford.

Bartlett’s writing is irrefutably magnetic, replete with confrontational ideas and delicious scorn. The staging on this occasion, as directed by Lucy Clements, gleams with emotional authenticity, although its humour feels needlessly subdued, and its politics ultimately shape up to be somewhat muted in effect. A reluctance to cast explicit and pointed judgement over Audrey, diminishes the dramatics that the story should be able to deliver.

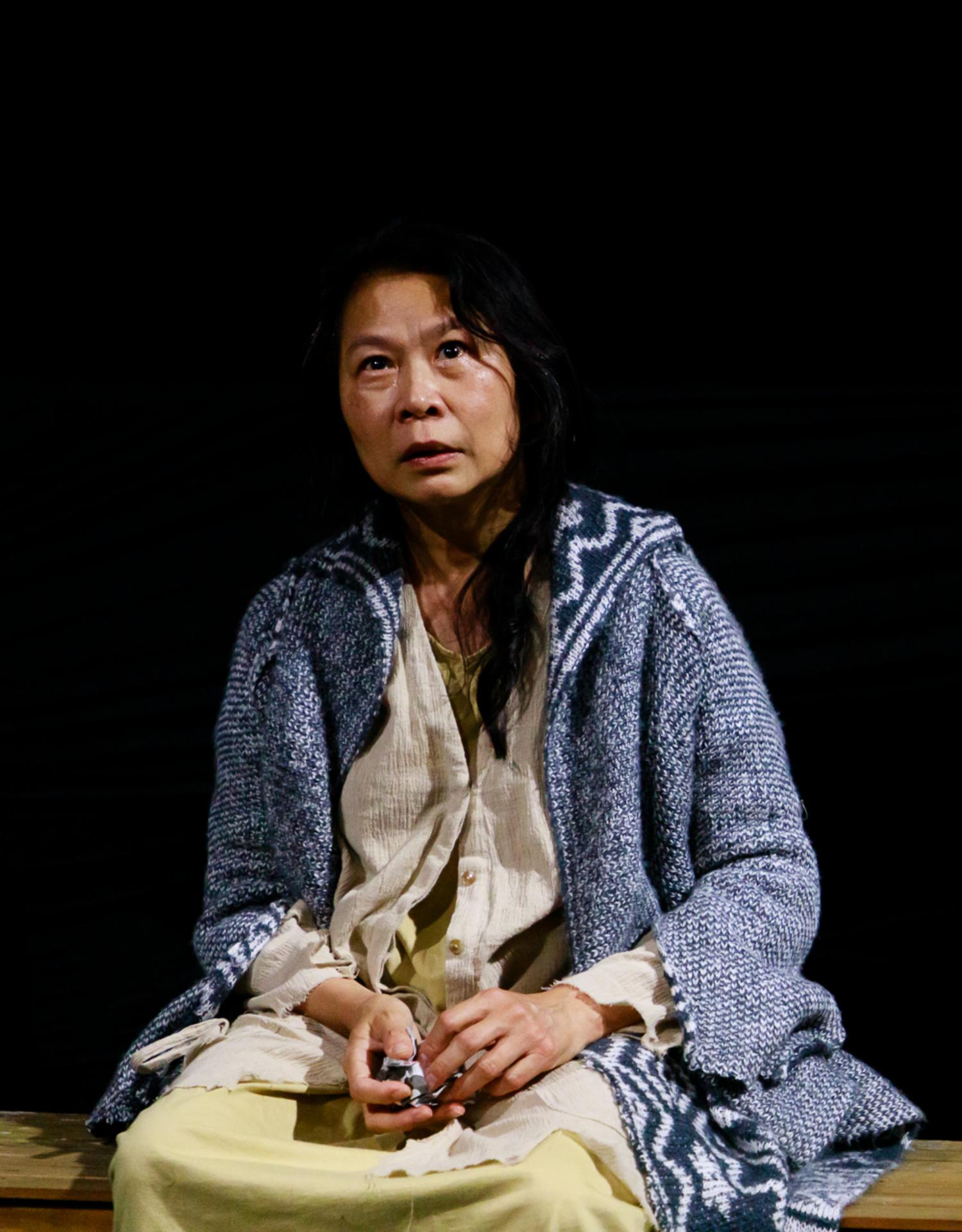

Actor Joanna Briant is a very convincing leading lady, with a performance that looks and feels consistently genuine, but other elements of the production bear a certain uncompromising earnestness that detracts from her work. Briant makes excellent choices at creating a personality who only thinks of herself as sincere and well-meaning, but other forces can work harder to create a sense of opposition to Audrey’s behaviour.

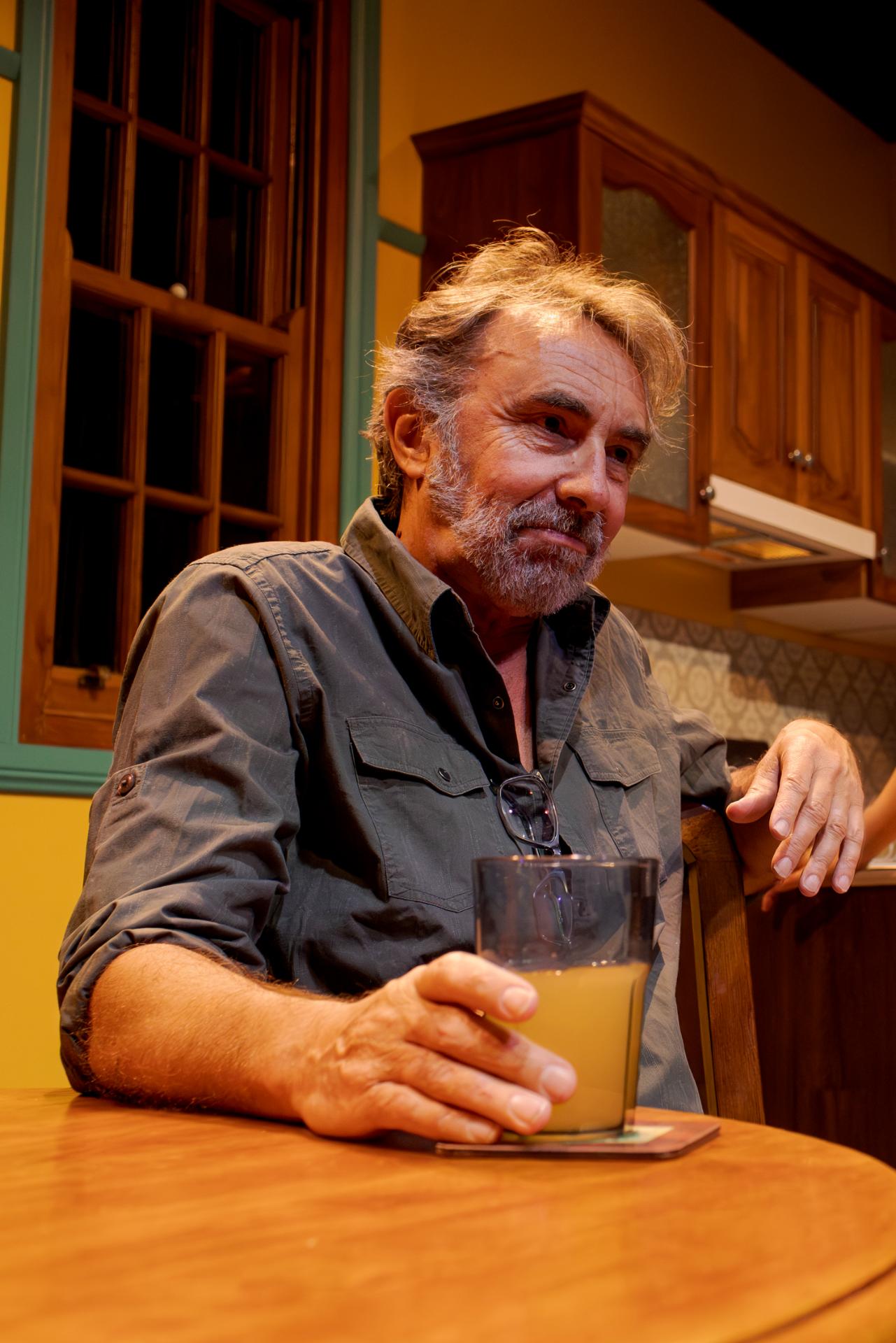

Thankfully, Briant’s is not the only strong performance from the cast. Claudette Clarke’s spirited defiance as Cheryl the ageing house cleaner, is a joy to watch, with an edgy abrasiveness that thoroughly elevates the presentation. Also highly persuasive is Charles Mayer, who plays Audrey’s ride-or-die lover Paul with a lightness of touch, humorously portraying the complicity of bystanders who have every opportunity to intervene but who choose to ride passively with the tides.

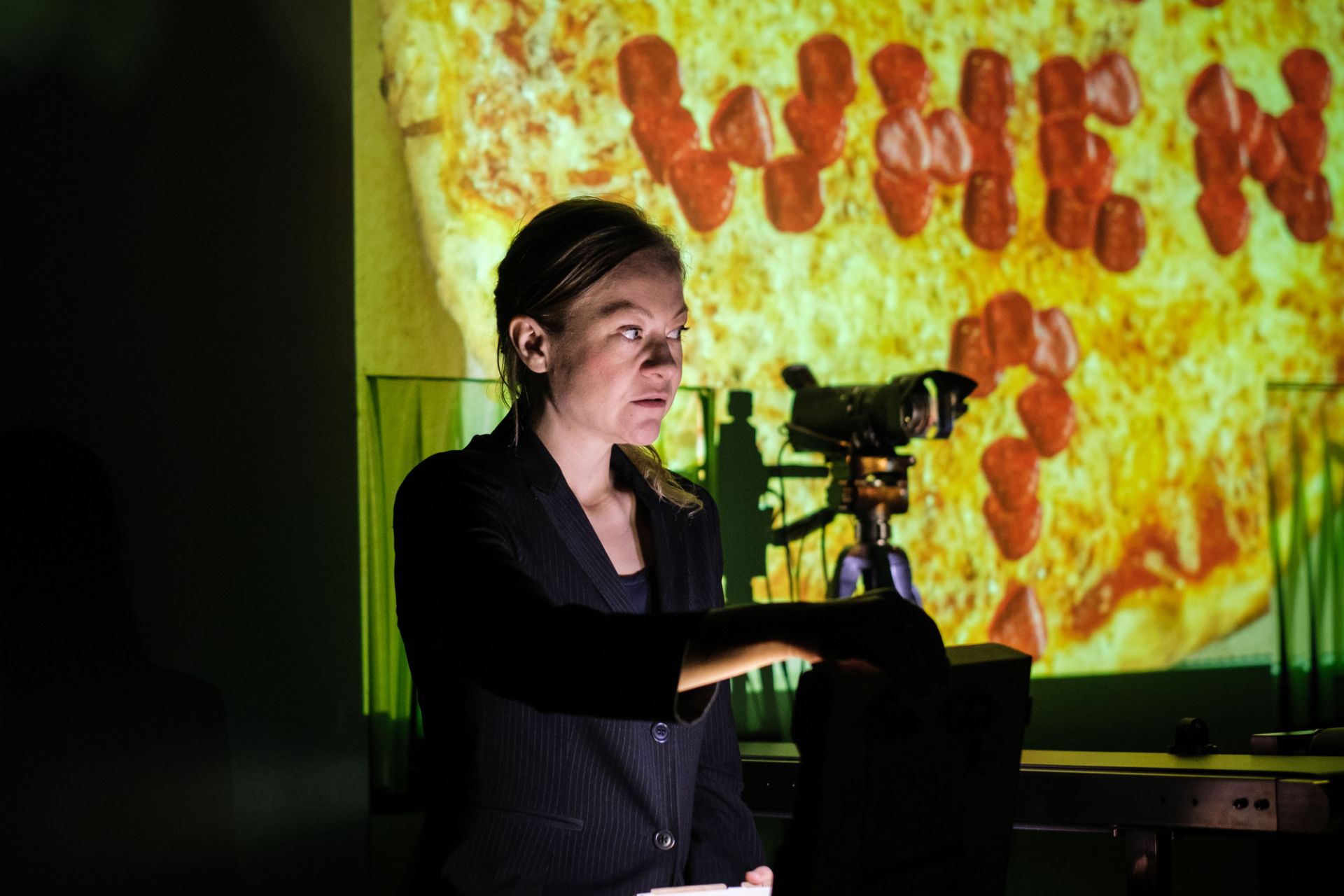

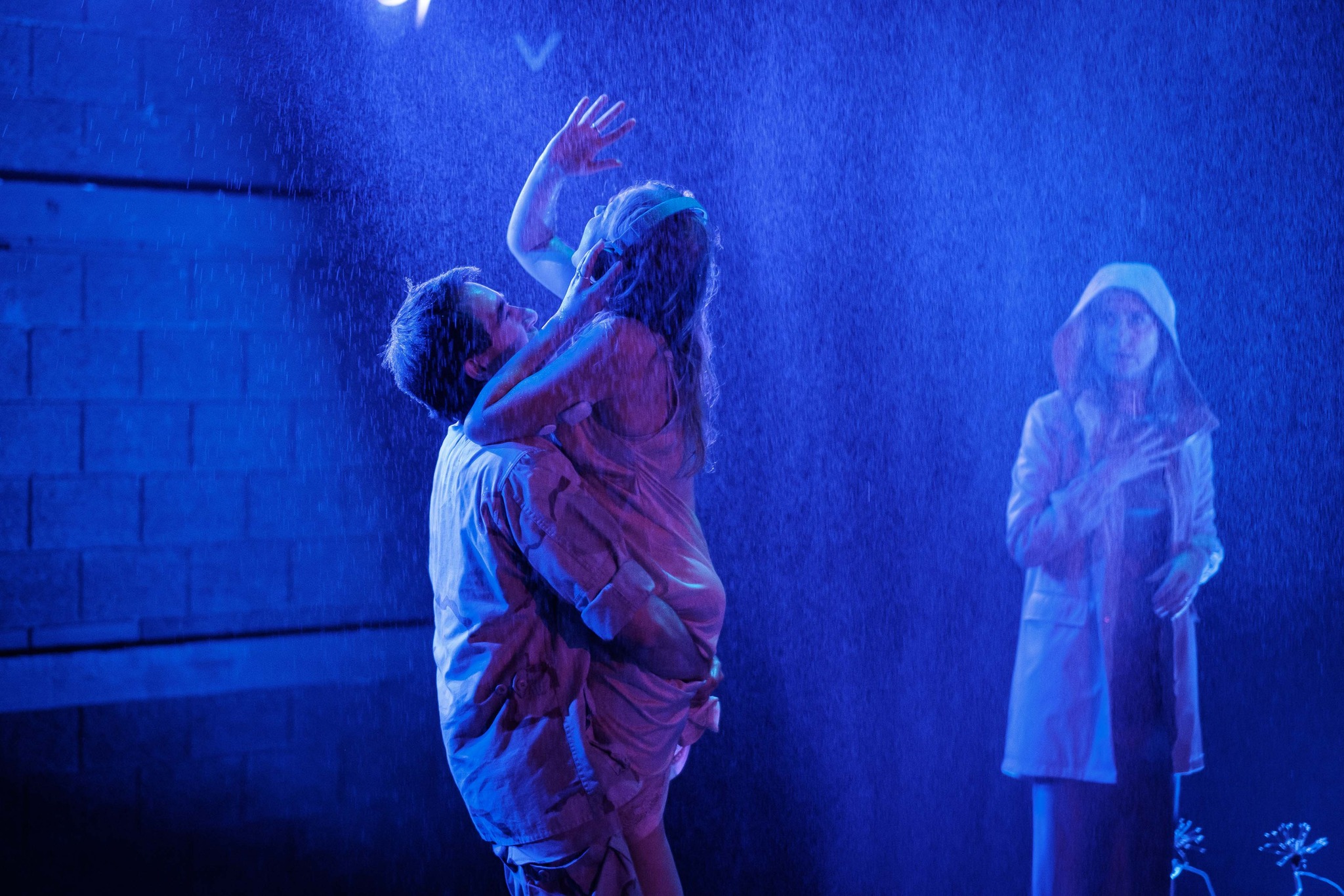

Imagery from this staging too, has its moments of glory. The collaboration between production designer Monique Langford and lighting designer Kate Baldwin, is a fairly ambitious one, able to invoke a grand landscape on foreign lands, with only the power of suggestion. Music and sound by Sam Cheng provide a gravity befitting the stakes involved, reminding us of the wider impact of these personal narratives.

Romantic nostalgia, the kind that Audrey is so invested in, represents a longing that those, for whom the system works, is bound to have. Of course Audrey is able to look back with rose-tinted glasses, now that she has her millions. There are others who simply cannot look at those symbolic structures, without having to wish for improvements. We do not regard icons with the same reverence, or indeed irreverence, because they mean different things to different people. The way in which we live our lives, have hitherto relied upon power discrepancies and injustices. Of course Audrey and her ilk will want to retain old things, but unless they can afford to make up for all the sacrifices, that the lower classes are no longer willing to submit to, then they too will have to move on with the times.

www.seymourcentre.com

Venue: Kings Cross Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Sep 27 – Oct 13, 2018

Venue: Kings Cross Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Sep 27 – Oct 13, 2018