Venue: Roslyn Packer Theatre (Sydney NSW), Mar 29 – May 11, 2025

Book and Lyrics: Tom Gleisner

Music: Katie Weston

Director: Dean Bryant

Cast: Evelyn Krape, Vidya Makan, Maria Mercedes, Eddie Muliaumaseali’i, John O’May, Christina O’Neill, Jackie Rees, Slone Sudiro, John Waters, Christie Whelan Browne

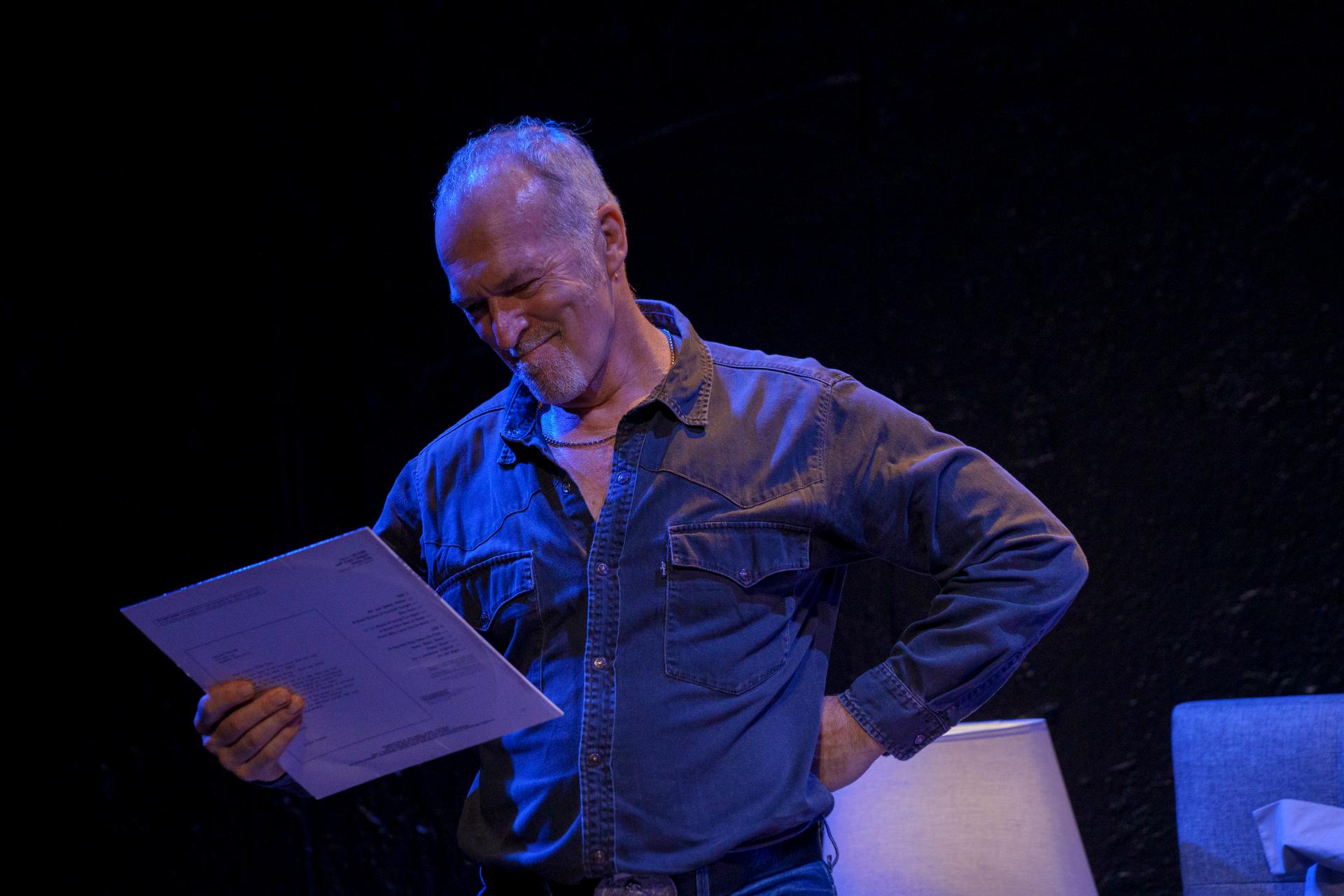

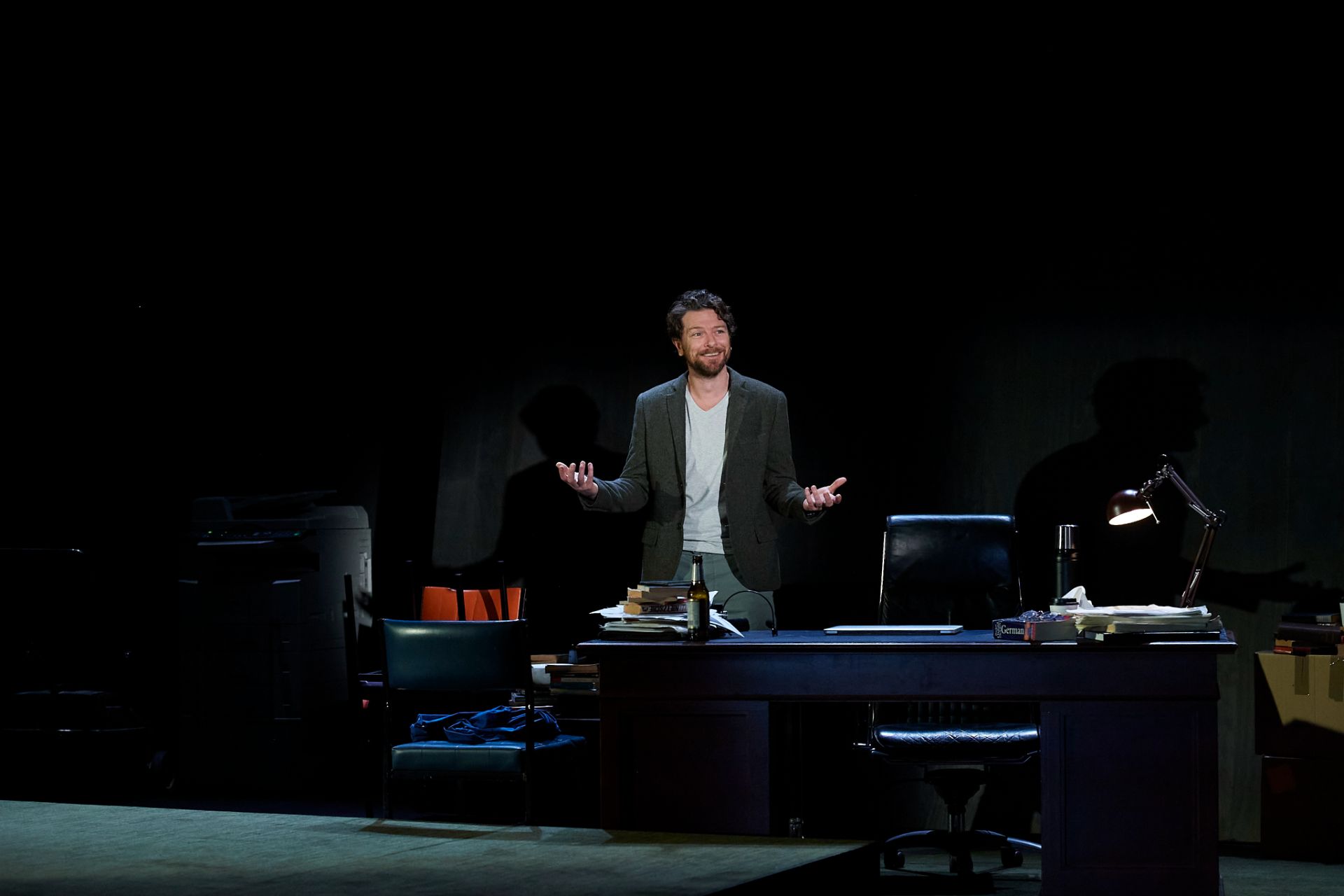

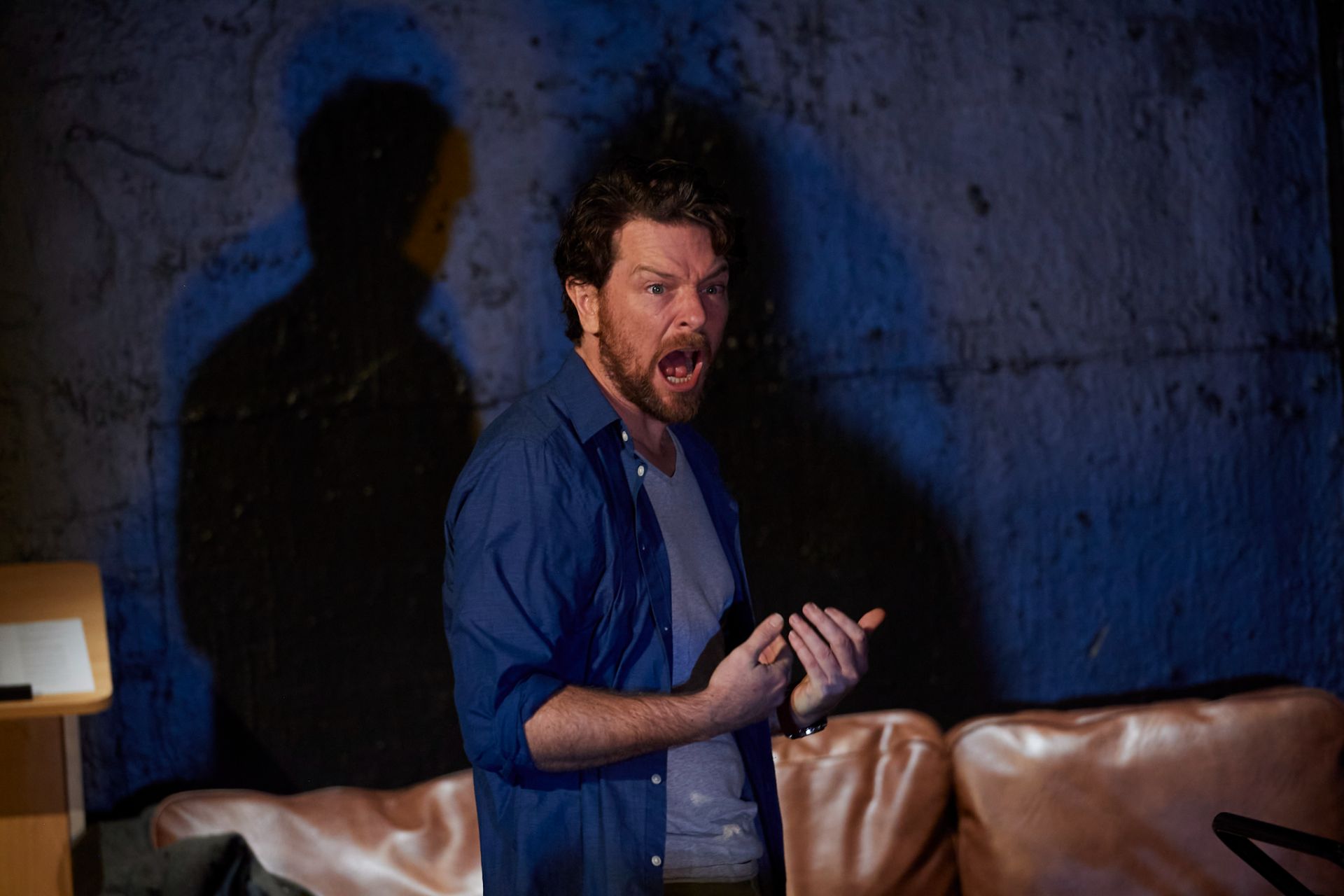

Images by Daniel Boud

Theatre review

One would hope that retirement homes are the most idyllic places in which the elderly can enjoy their twilight years, but Pine Grove is no such institution. In Tom Gleisner’s musical comedy Bloom, senior residents are treated with no respect, by a management that thinks only of the bottom line. The characters we encounter in Gleisner’s writing are thoughtfully assembled, but his plot unfolds predictably at every juncture, and a clichéd sense of humour guides the tone for the entire presentation.

Direction by Dean Bryant demonstrates little need for inventiveness, focussing efforts instead on creating a show that speaks with poignancy and tenderness. Its efficacy as a heart-warming tale is however debatable, with some viewers likely to respond favourably to its sentimentality, while others may be left unmoved by its hackneyed approach. The music of Bloom, written by Katie Weston and directed by Lucy Bermingham, is somewhat pleasant but the thorough conventionality of its style might prove uninspiring for some.

Set design by Dann Barber, along with costumes by Charlotte Lane, are appropriately and intentionally drab for a story about the failures of aged care systems. Lights by Sam Scott too, fulfil with unquestionable proficiency, the practical requirements of the simple narrative.

The ensemble is commendable for the gleam it brings to Bloom, with their confident singing and spirited delivery of old-school comedy, ensuring a consistent sense of professionalism. Performer Christie Whelan Browne is especially noteworthy for her flamboyant approach, in the hilarious role of Mrs MacIntyre the dastardly owner of Pine Grove. As staff member Ruby, Vidya Makan’s big voice is a treat and a memorable feature, in a production that has a tendency to feel more than a little tired.

Venue: Roslyn Packer Theatre (Sydney NSW), Apr 27 – May 29, 2021

Venue: Roslyn Packer Theatre (Sydney NSW), Apr 27 – May 29, 2021

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Nov 1 – Dec 14, 2019

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Nov 1 – Dec 14, 2019

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Mar 29 – May 19, 2018

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Mar 29 – May 19, 2018

Venue: Wharf 1 Sydney Theatre Company (Walsh Bay NSW), Aug 28 – Oct 17, 2015

Venue: Wharf 1 Sydney Theatre Company (Walsh Bay NSW), Aug 28 – Oct 17, 2015