Venue: Kings Cross Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Jun 8 – 18, 2022

Playwright: Cassie Hamilton

Director: LJ Wilson

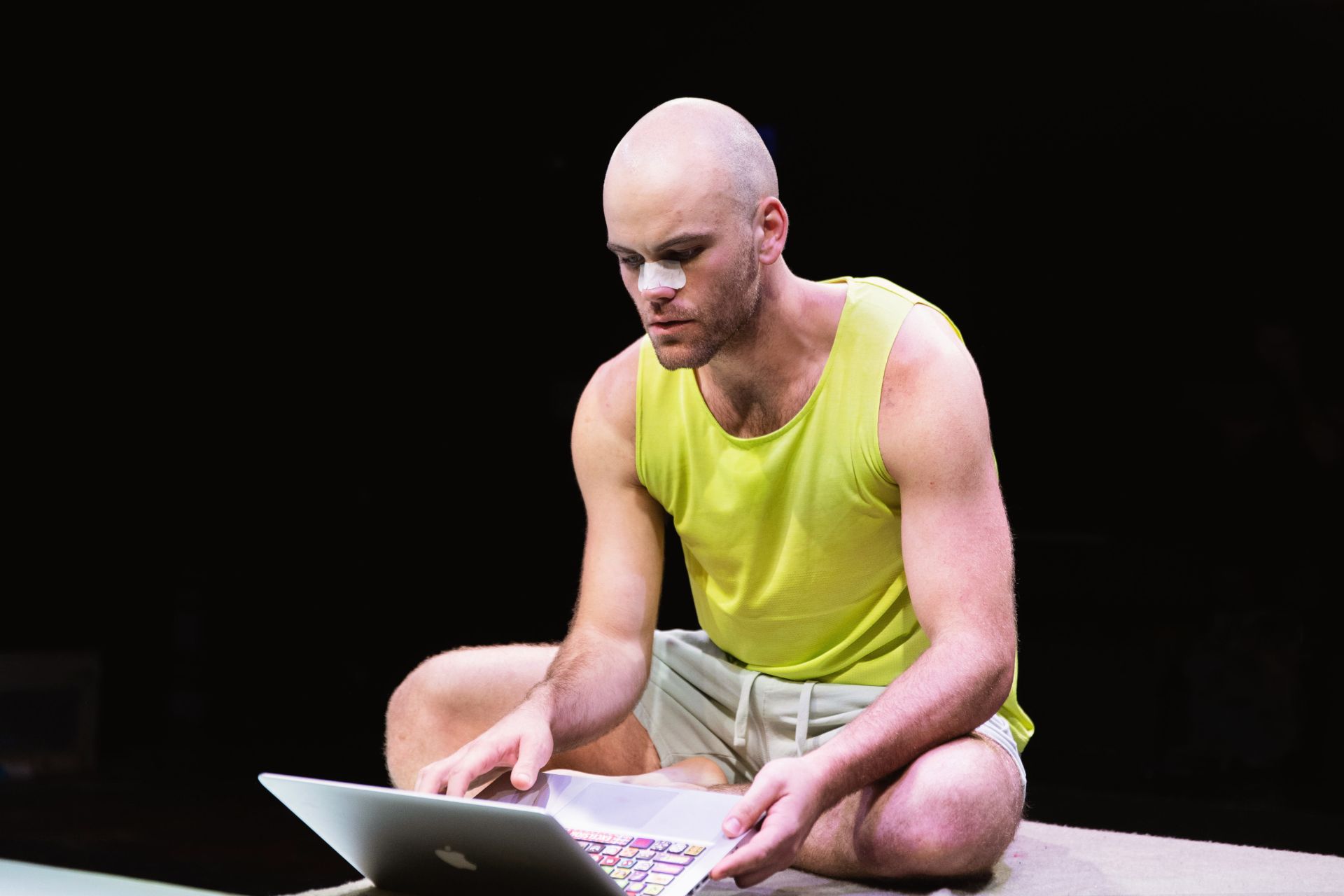

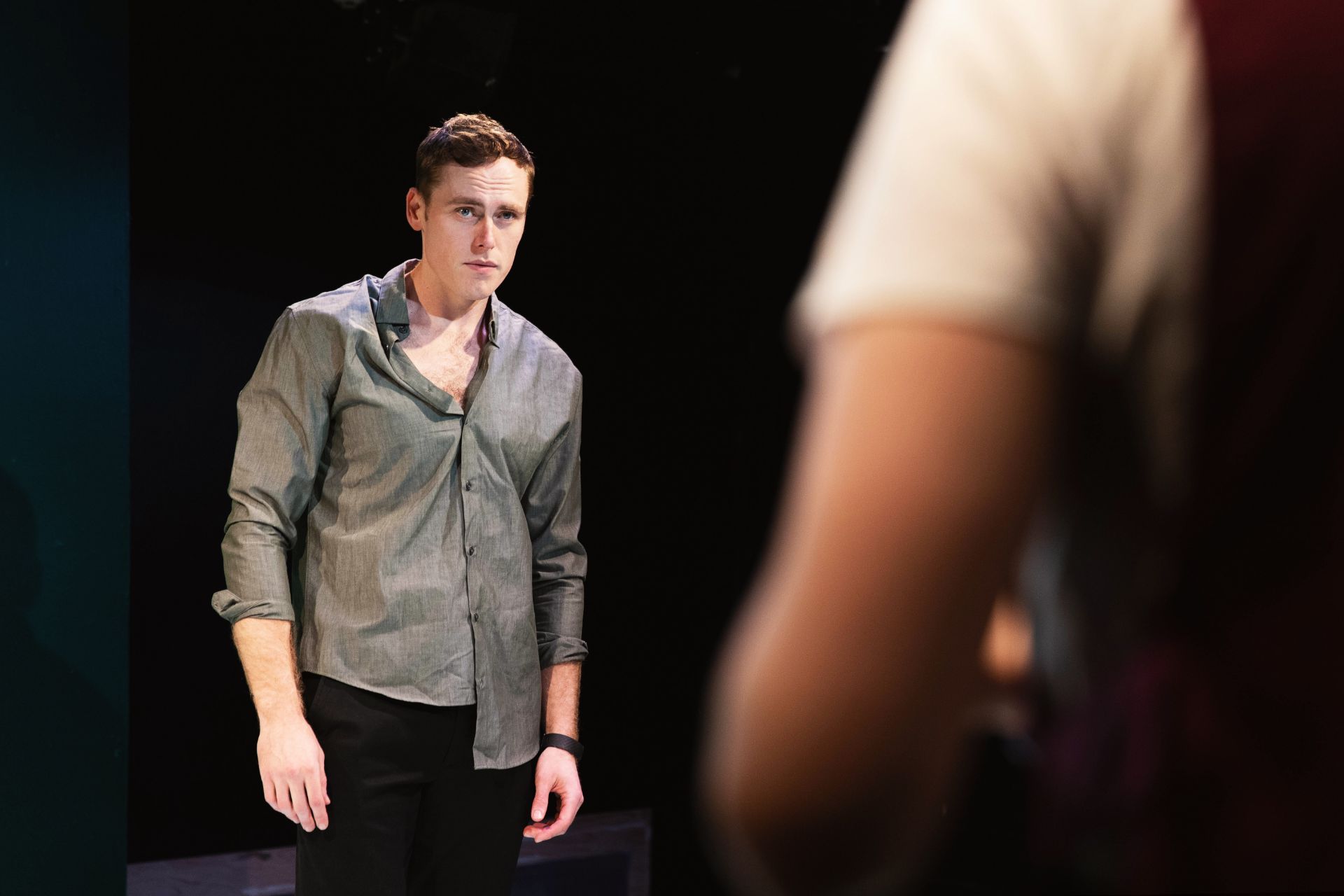

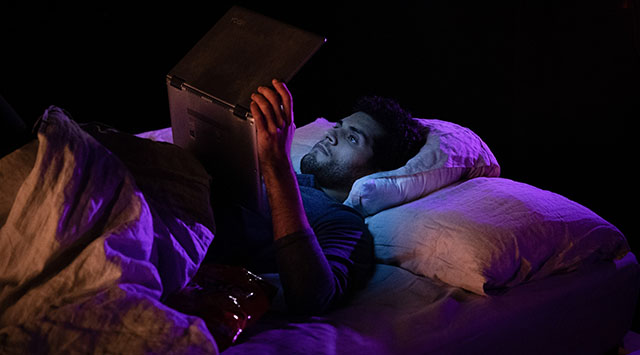

Cast: Sarah Greenwood, Clay Crighton, Jack Francis West

Images by Snatched Theatre Collective

Theatre review

In Cassie Hamilton’s Daddy Developed a Pill, Cynthia’s father strikes it rich, after inventing a drug that becomes hugely popular. The sudden change in lifestyle means that Cynthia no longer gets to see her father regularly. Feeling neglected, she grows into adulthood desperately trying to win his approval, and forms the belief that by creating a pill of her own, she would be speaking her father’s language, and thus able to regain his attention.

It might be a relatively simple narrative, but the plot of Hamilton’s play is complicated. 16 characters weave in and out, in an intentionally chaotic melange of short sequences, with rapid fire dialogue of which the audience is likely to only retain a small portion. The chronology of action seems erratic, but we are not the only ones confused. Cynthia is at the centre of all the hullaballoo, and she too is bewildered. Indeed, her existence is one of alienation and uncertainty. She stands outside, as though in a state of dissociation, whilst lovers, family and work associates, are fussing over her, caught up in dramas about Cynthia, while all she wants is her father.

Direction by LJ Wilson is relentlessly raucous. The entire show takes on the tone of a riotous comedy, but it is never truly funny. Even though the laughs are sporadic, much of the presentation proves captivating. The sheer energy of the staging sustains our interest, if only out of curiosity, for this rare occurrence of outrageously exuberant absurdism.

Rowan Yeomans’ sound and music are consistently lively, with a penchant for manufacturing an atmosphere of euphoria, to accompany the madcap performance style. Production design by Kate Beere is all glitz and camp, to invoke the vaudeville tradition. Jesse Grieg’s lights are flamboyant and colourful, adding great visual dynamism to proceedings.

Actor Sarah Greenwood as Cynthia is to be commended for conveying emotional authenticity, throughout the 95 minutes of ceaseless pandemonium. Clay Crighton and Jack Francis West are wonderfully animated with their extensive repertoire of roles, both impressive with the vigour they bring to the stage, and with the irrepressible mischievousness that accompany all the surreal hijinks they deliver. This team of three is remarkably well-rehearsed; the fluency with which they execute this intricate and convoluted work, is quite a sight to behold.

Cynthia struggles to find herself, because she feels unloved. Her father’s absence creates a hole that she seems unable to fill, yet life goes on. In Daddy Developed a Pill, it is the daughter who is left broken, and for those of us who recognise ourselves in that state of ruin, it is that honest depiction of a lack of closure, that resonates. Too much of our storytelling wants to offer catharsis, with sweet endings to sad tales. What seems more truthful on this occasion, is to see that we often experience no closure, only a hope that resilience accrues with each blow, and we simply keep going.

Venue: Kings Cross Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Apr 2 – 17, 2021

Venue: Kings Cross Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Apr 2 – 17, 2021

Venue: Kings Cross Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Mar 5 – 20, 2021

Venue: Kings Cross Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Mar 5 – 20, 2021

Venue: Kings Cross Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Feb 17 – 27, 2021

Venue: Kings Cross Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Feb 17 – 27, 2021