Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Jun 7 – Jul 13, 2025

Playwright: Eamon Flack (from the novel by Helen Garner)

Director: Eamon Flack

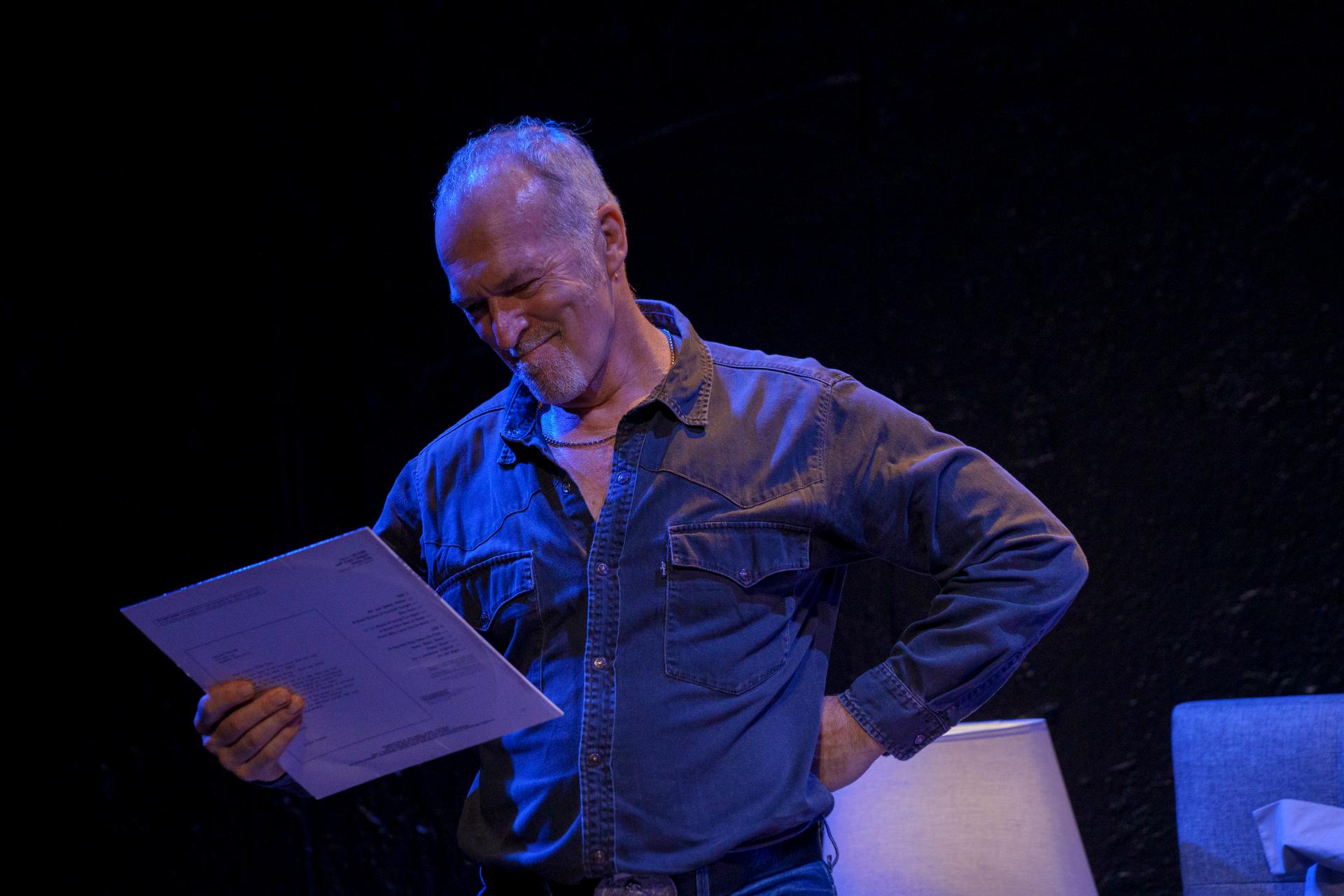

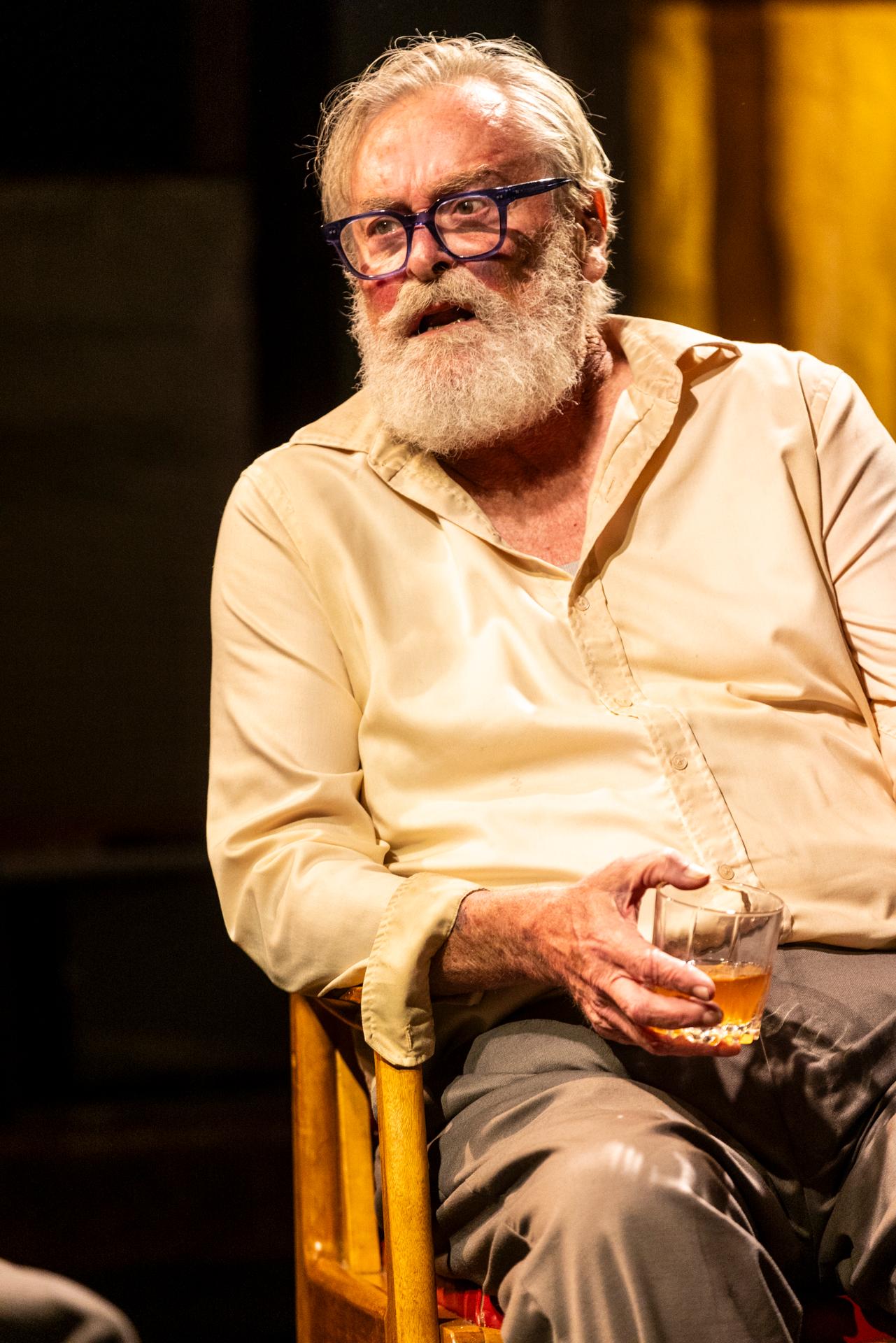

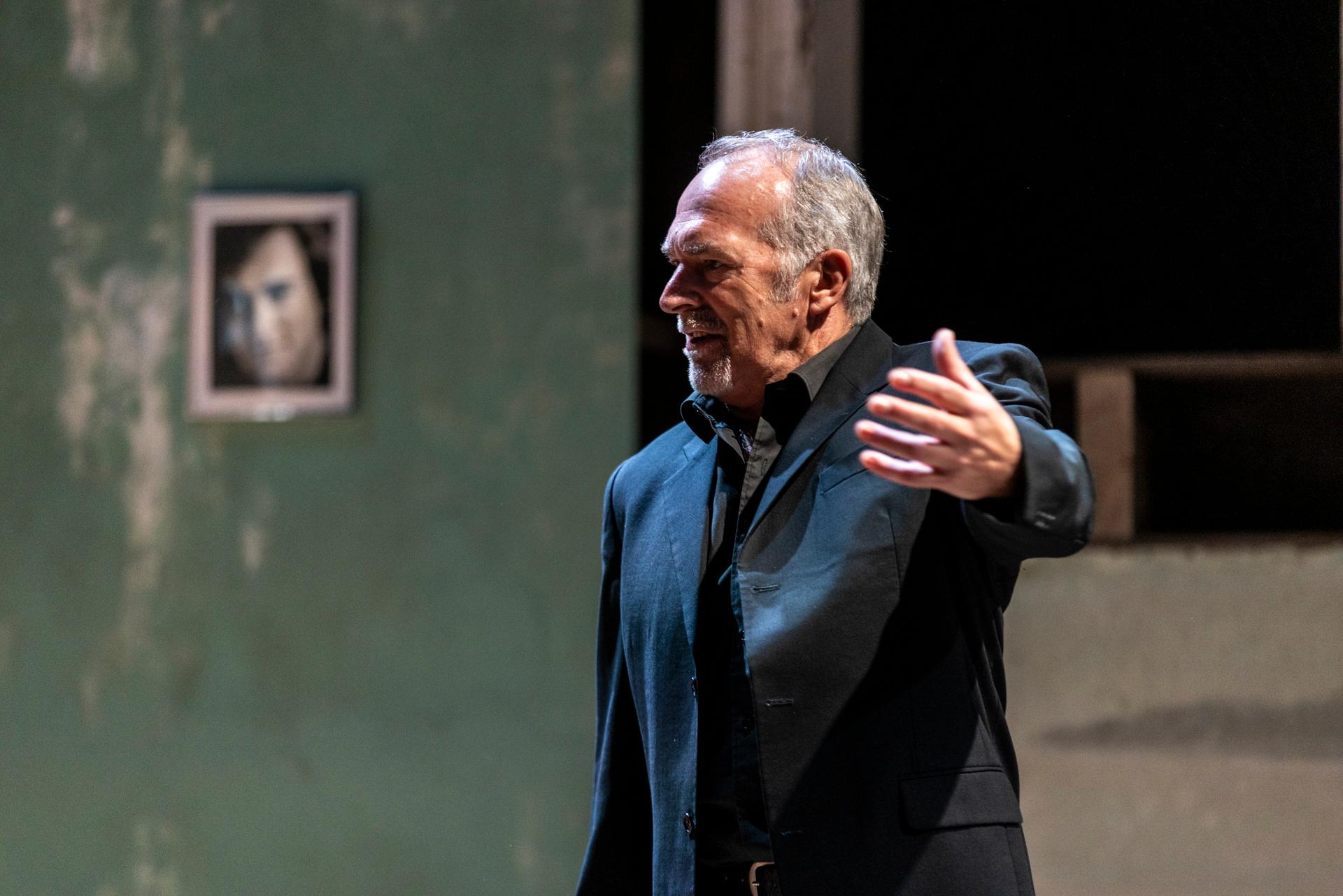

Cast: Elizabeth Alexander, Judy Davis, Emma Diaz, Alan Dukes, Hannah Waterman

Images by Brett Boardman

Theatre review

Nicola is spending a few weeks in Melbourne, as she undergoes “alternative cancer treatment”. Helen has volunteered as carer through the ordeal, completely unconvinced by the bogus claims of the expensive but unsubstantiated therapies. Helen Garner’s 2008 novel The Spare Room deals with sickness and death, from the perspectives of those who are terminally ill, and those close to them.

Adapted by Eamon Flack, this theatrical version is thankfully humorous in tone, even if it does delve deep into difficult subject matter. What it discusses is certainly worthwhile, considering its universality, and its somewhat taboo nature only makes the experience more meaningful. The show is mostly an engaging one, even if performers seem consistently under-rehearsed. Judy Davis as Helen has a tendency for physical exaggeration, while Elizabeth Alexander as Nicola is overly trepidatious, but notwithstanding these imperfections, both are able to tell the story convincingly.

To address the practical requirements of the text, set design by Mel Page incorporates elements that are disparately homely and clinical, leaving the space to languish in an awkward intermediary, never really conveying any believable locale. Paul Jackson’s lights offer intricate atmospheric enhancements, as does music by Steve Francis, notable for being performed live by a very attentive Anthea Cottee on her trusty cello.

At her time of need, Nicola becomes hugely demanding of her friends and family. Her friends and family in turn discover, that there are no burdens more special than those of a loved one, in their final moments.