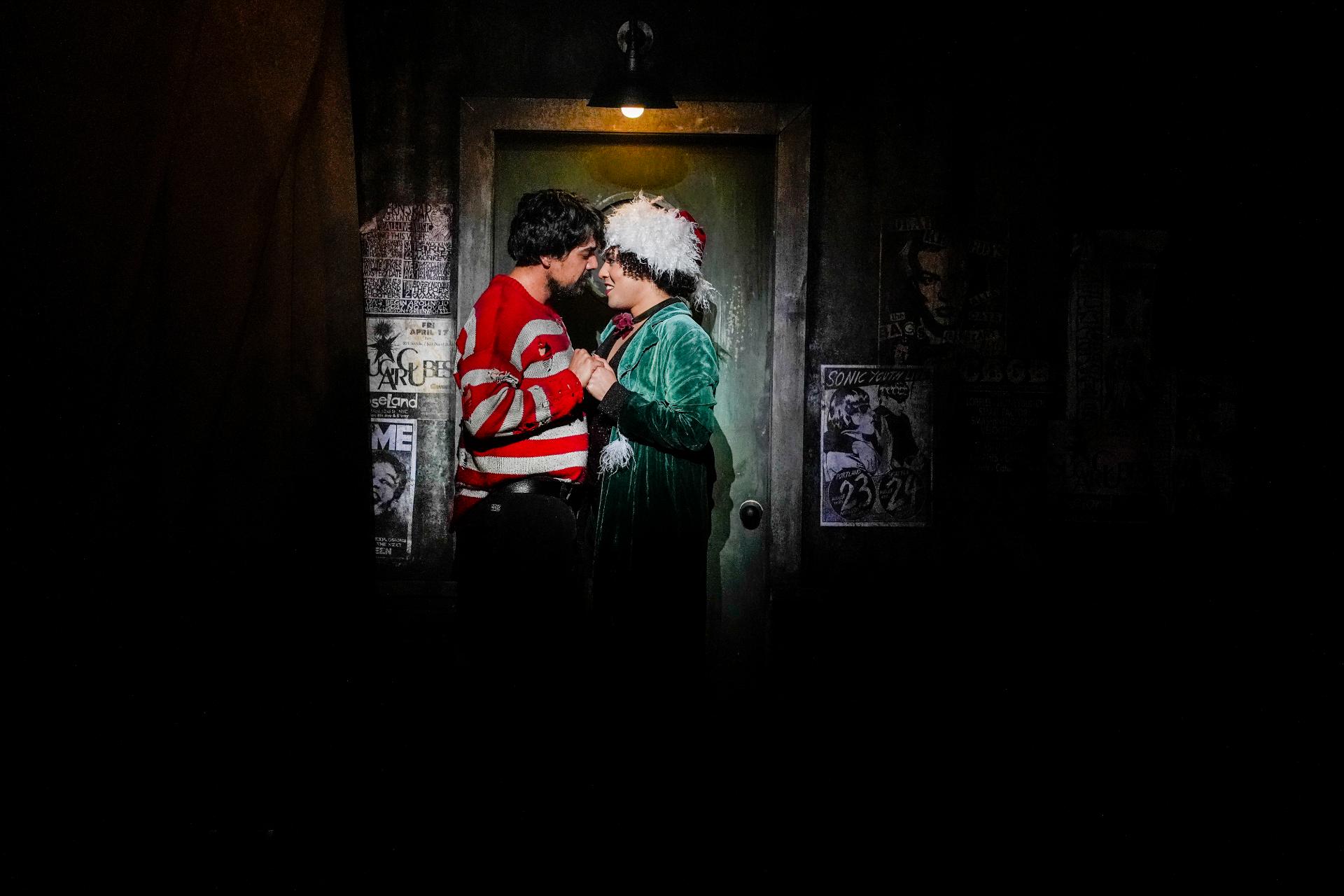

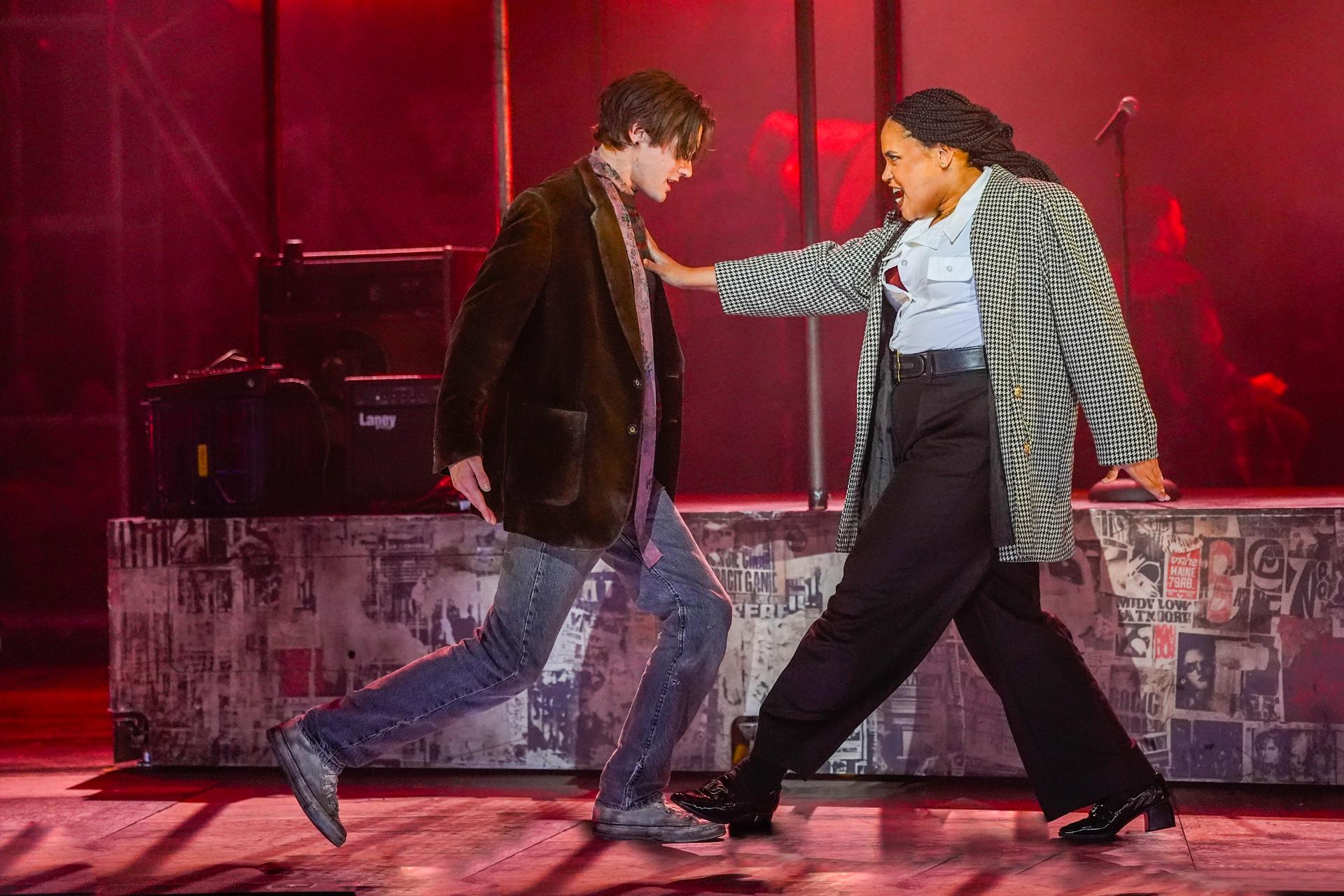

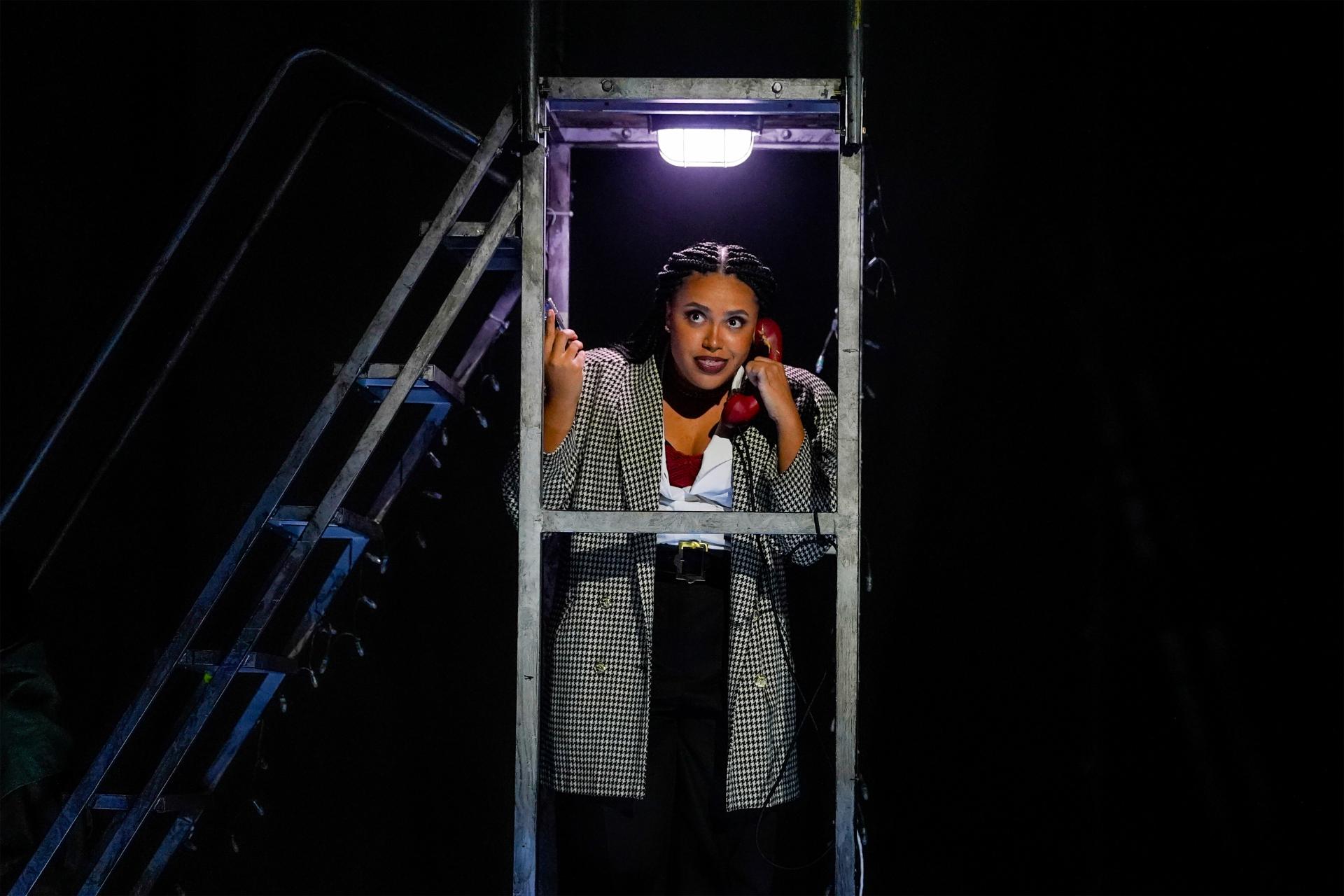

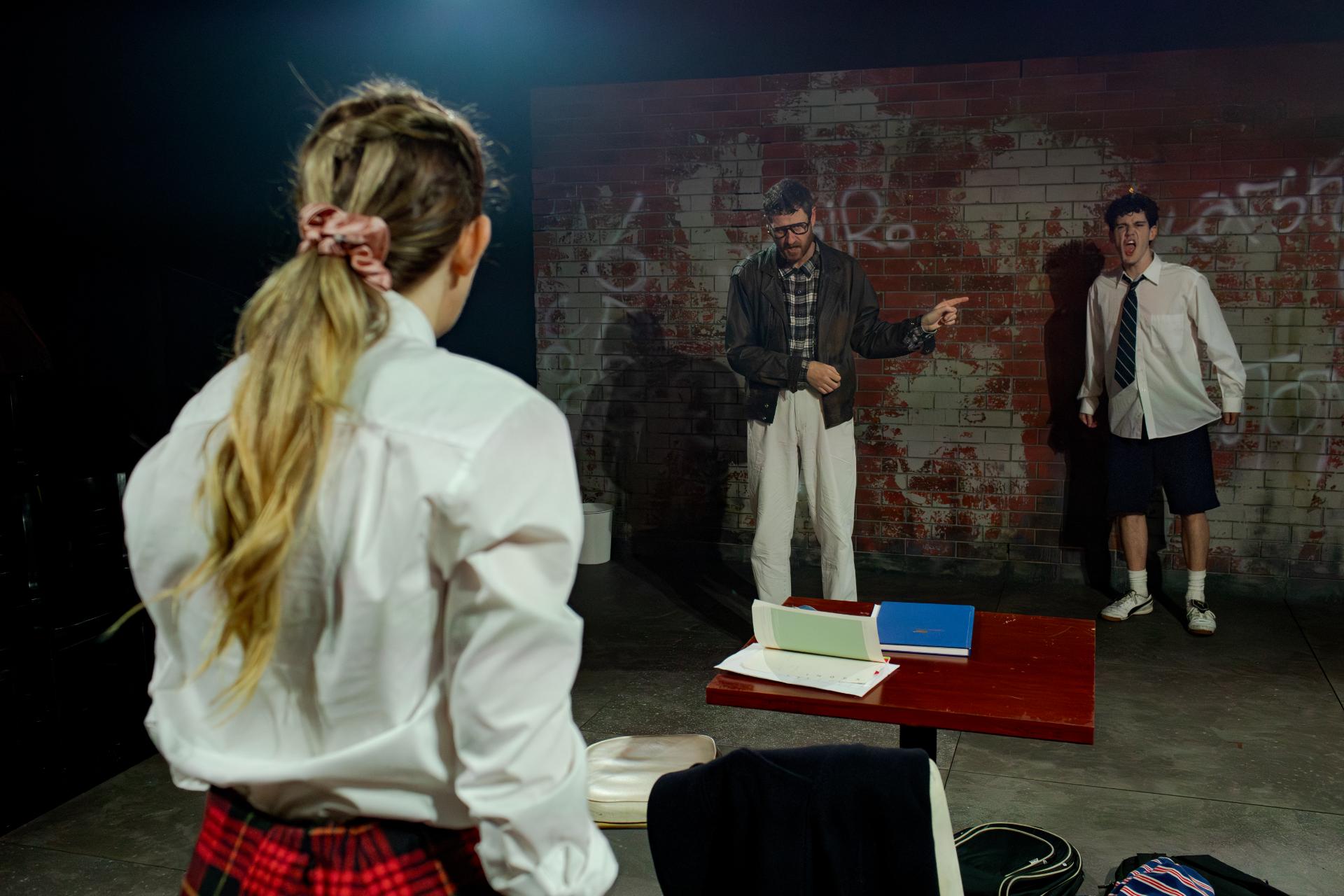

Venue: The Rebel Theatre (Sydney NSW), Oct 15 – 18 , 2025

Playwright: Honor Webster-Mannison

Director: Luke Rogers

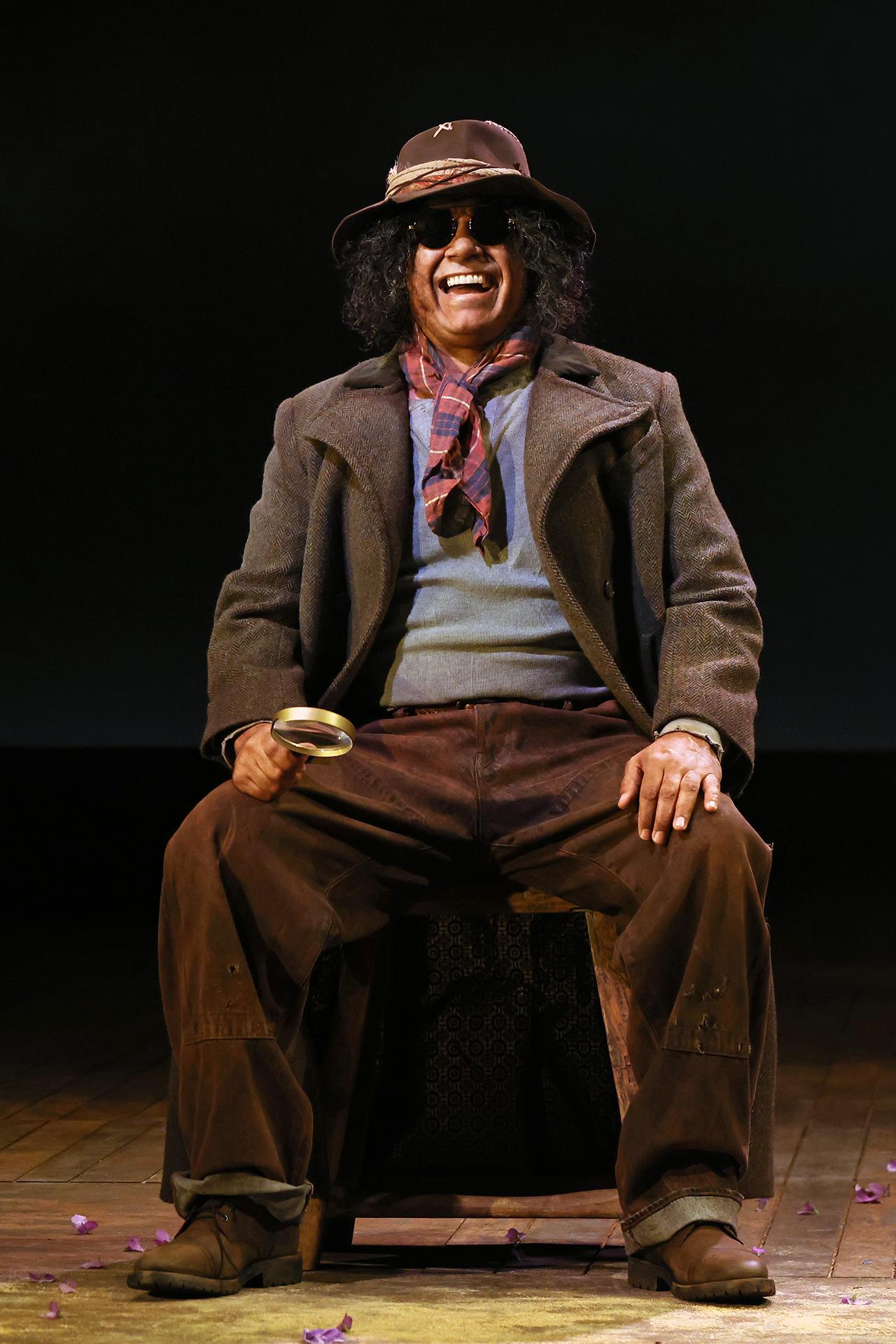

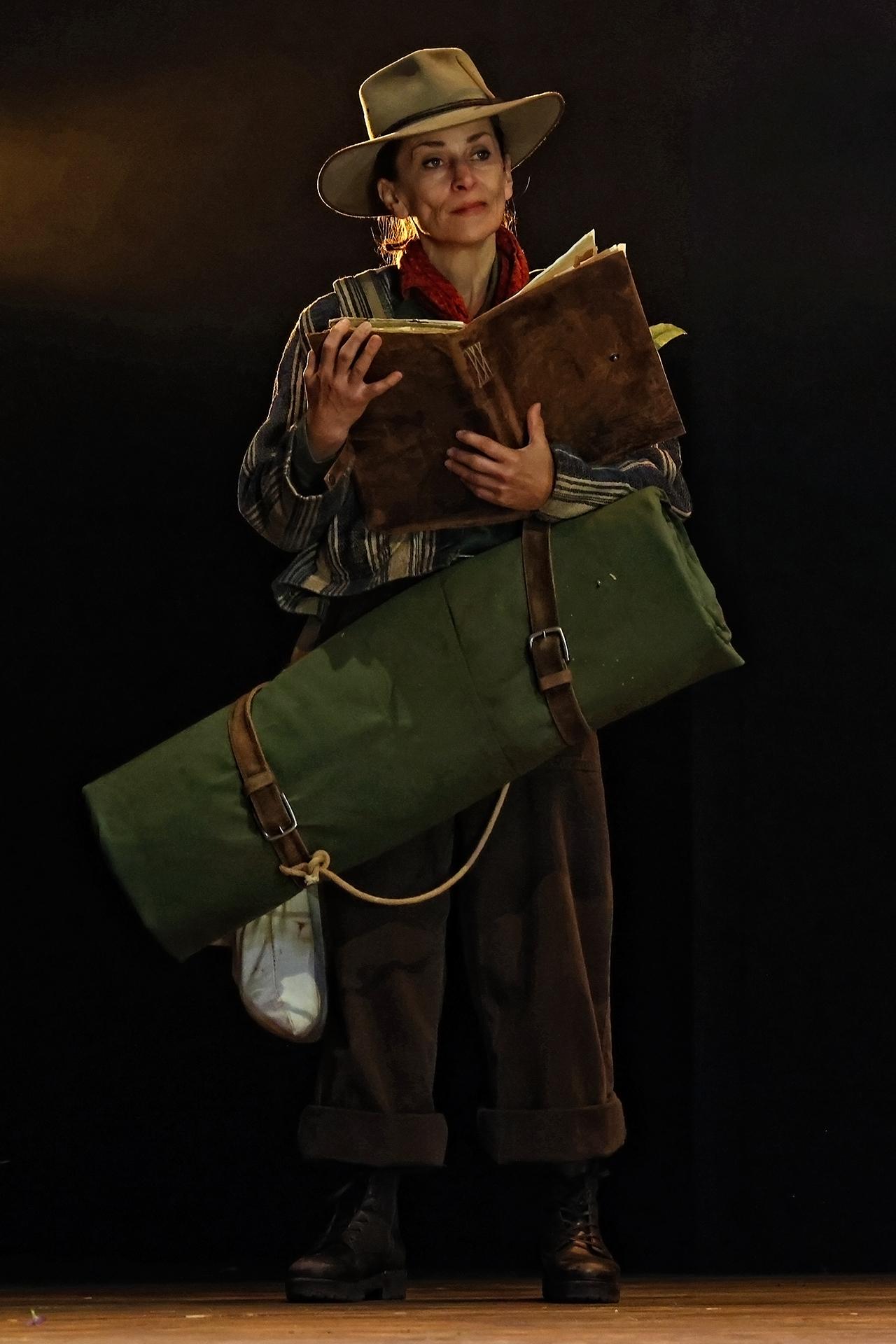

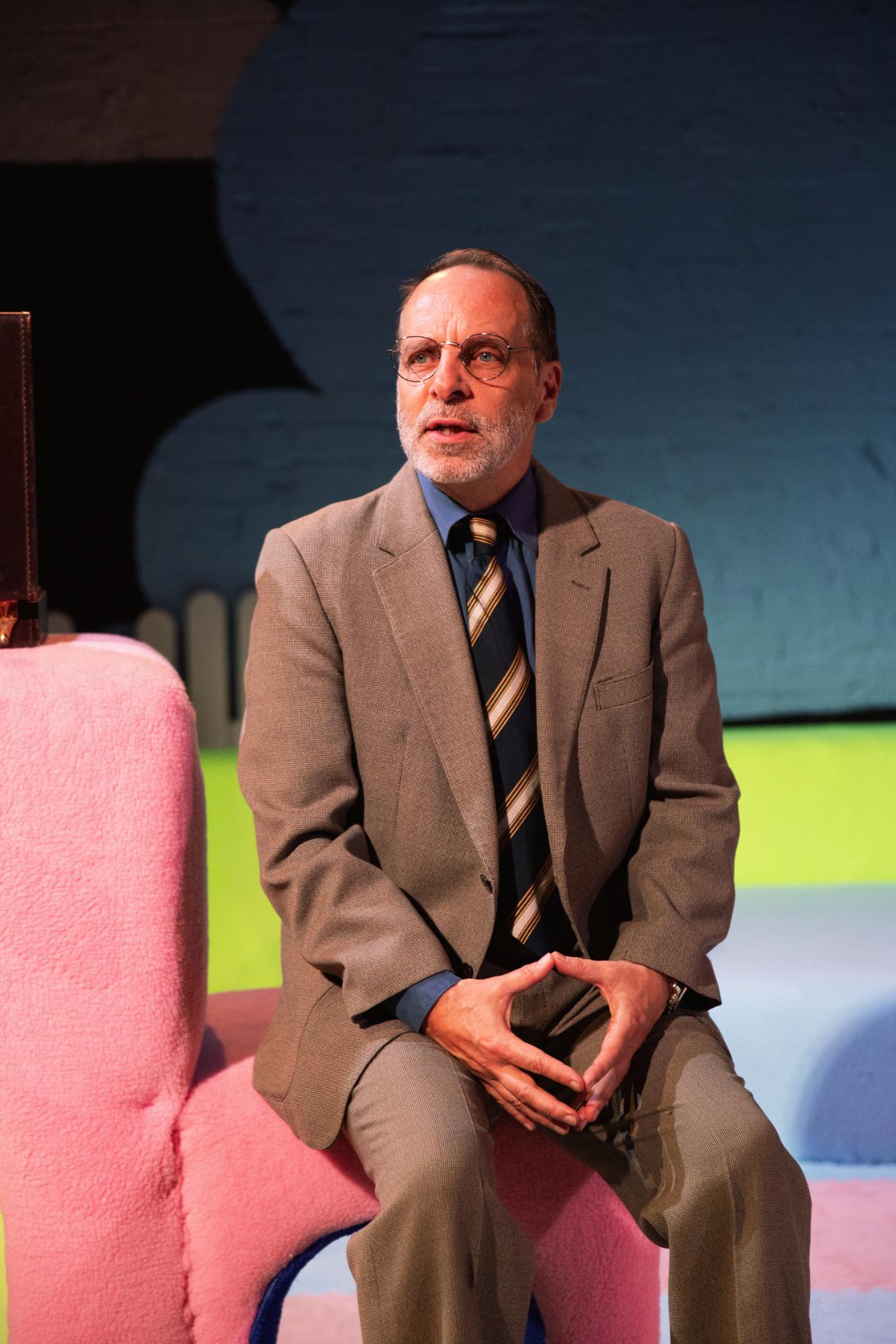

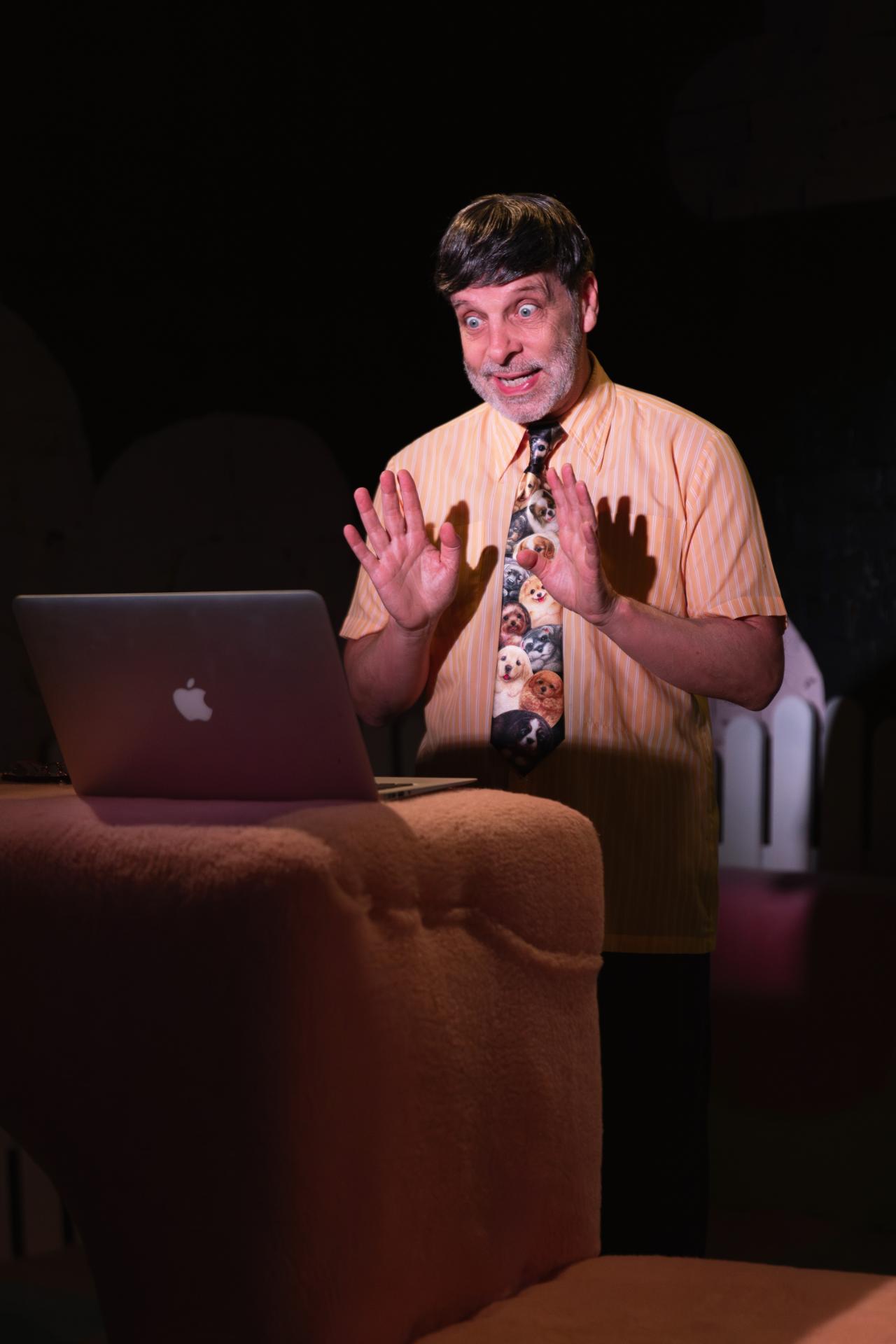

Cast: Georgie Bianchini, Hannah Cornelia, Kathleen Dunkerley, Quinn Goodwin, Matthew Hogan, Blue Hyslop, Sterling Notley, Emma Piva

Images by

Theatre review

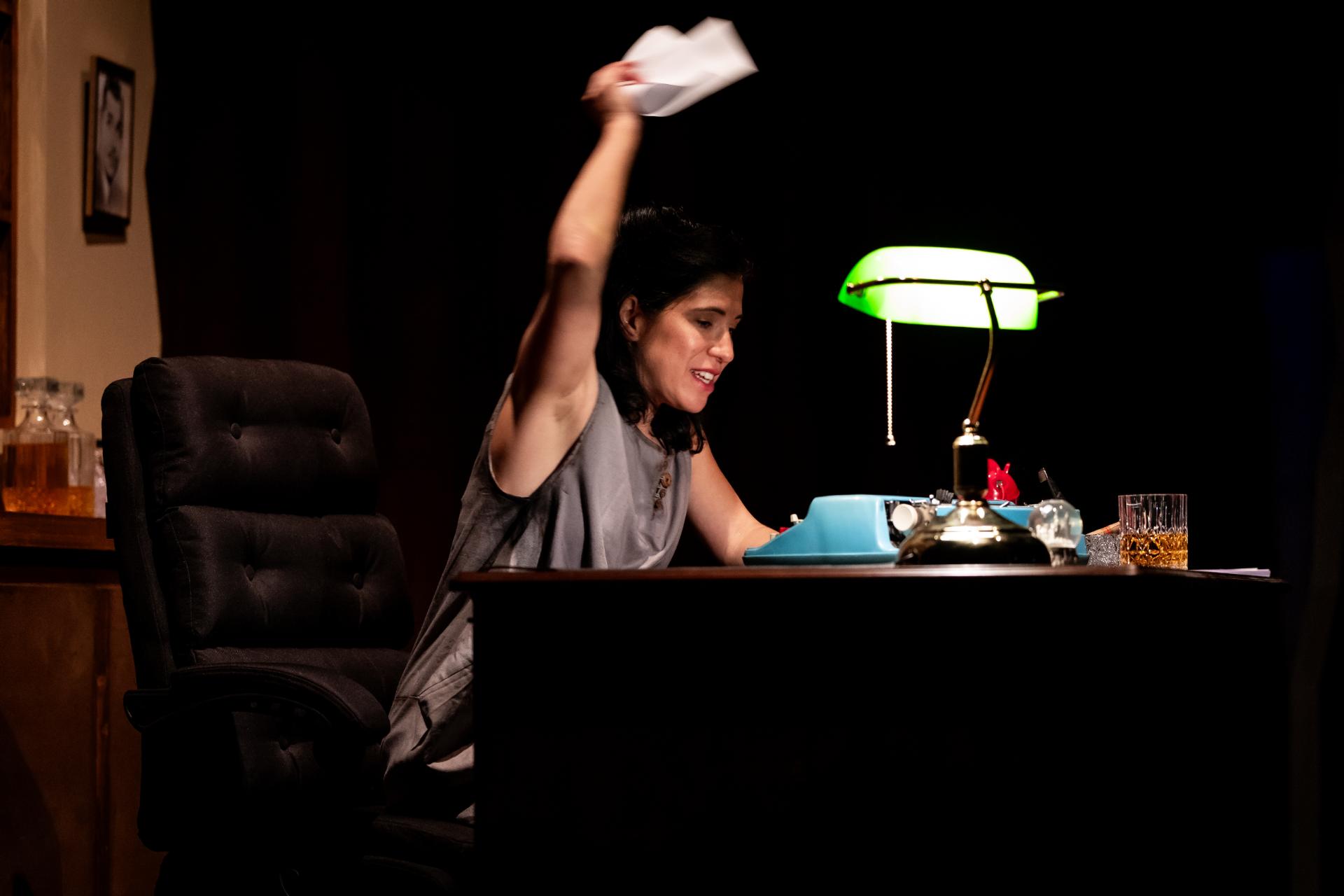

Chaos is the natural order in a fast-food restaurant, where young workers hold down the counters and, by extension, the bottom tiers of vast corporate empires. Honor Webster-Mannison’s Work, But This Time Like You Mean It announces its irony from the title, a wry invitation to reflect on labour, performance, and disillusionment. The play mines humour from the everyday grind, though its observations rarely move beyond the familiar. Still, the writing’s energy and authenticity make it a fertile ground for theatrical invention.

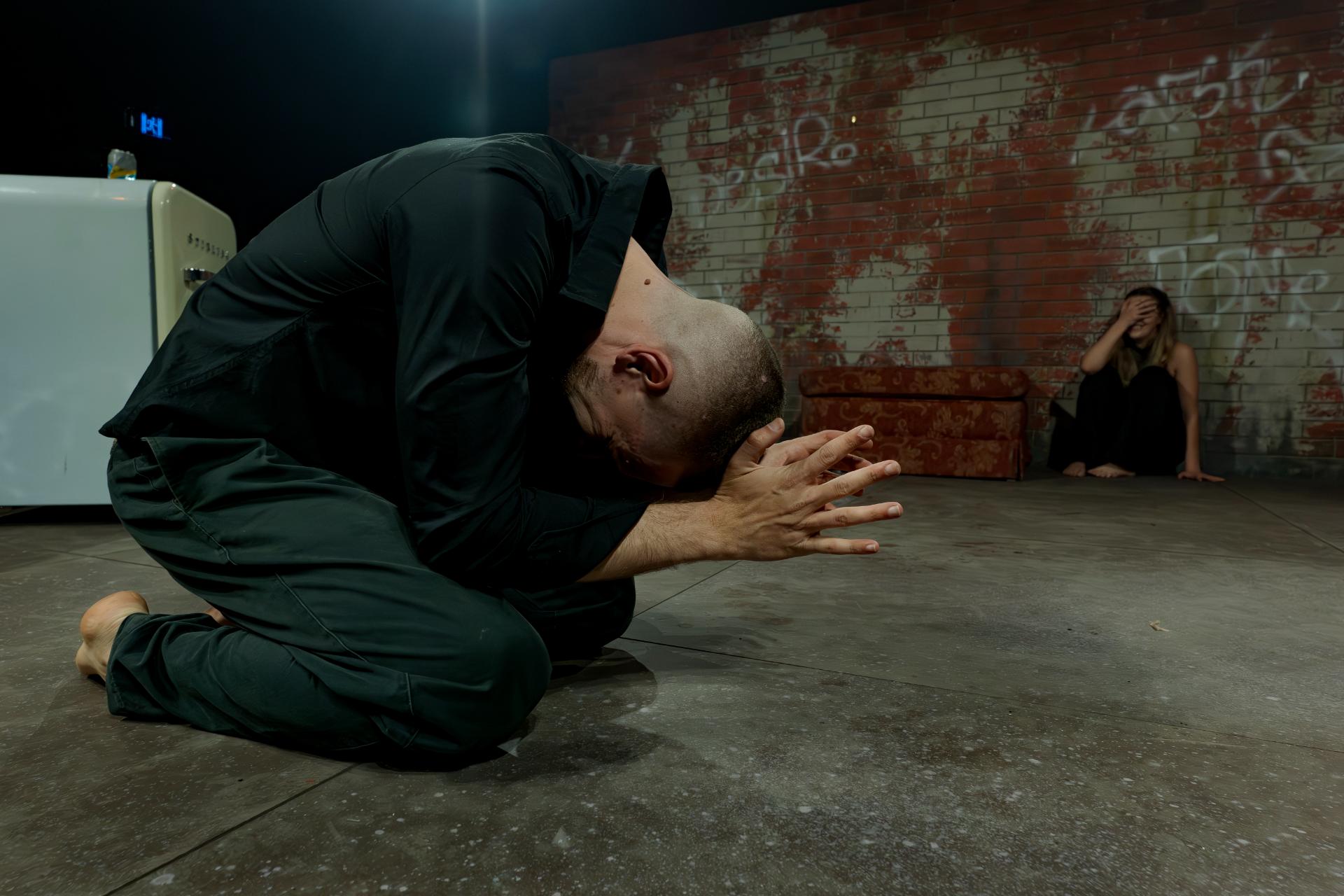

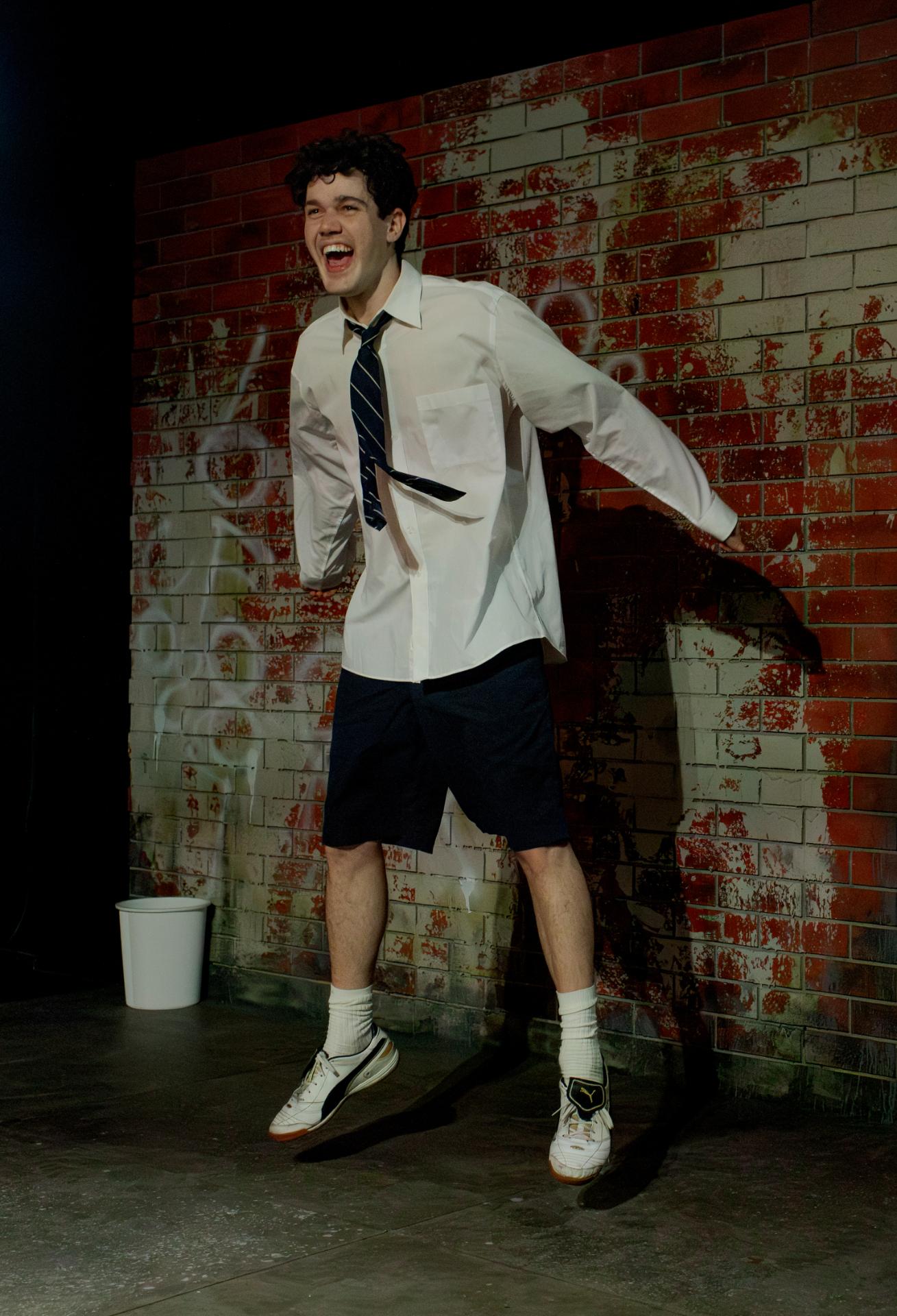

Directed by Luke Rogers, the production delivers amusement in spades, impressing with its relentless energy and visual exuberance. Set within the bleak confines of a takeout joint, Rogers’ staging transforms the banal into the spectacular, revealing the latent drama of labour and exhaustion.

Kathleen Kershaw’s set is both playground and pressure cooker, facilitating agile movement while immersing us in vivid, layered visuals. Ethan Hamill’s lighting gives the work structure and momentum, while Patrick Haesler’s sound design further heightens atmosphere and tension, ensuring the production maintains a constant sense of urgency and rhythm. Together, these elements generate a rhythm that feels breathless yet purposeful, a choreography of survival rendered with theatrical bravado.

A cast of eight delivers the show’s discombobulating heart with infectious precision and energy. Their performances are tightly honed, radiating a cohesion and verve that keep the audience engaged from start to finish. As the beleaguered branch manager, Blue Hyslop stands out for both charm and nuance, balancing comic timing with moments of surprising emotional depth amid the surrounding mayhem.

Work, But This Time Like You Mean It presents entry-level work as both crucible and classroom, a space where identities are forged under pressure, and where the absurd machinery of labour dispenses its quiet lessons in endurance. It exposes the inevitability of our initiation into capitalism, especially at an age too young to grasp its traps, when the thrill of a first job disguises the real lesson: that the system always starts by teaching us how to stay in line.