Venue: Ensemble Theatre (Kirribilli NSW), Oct 10 – Nov 22, 2015

Venue: Ensemble Theatre (Kirribilli NSW), Oct 10 – Nov 22, 2015

Playwright: David Hare

Director: Mark Kilmurry

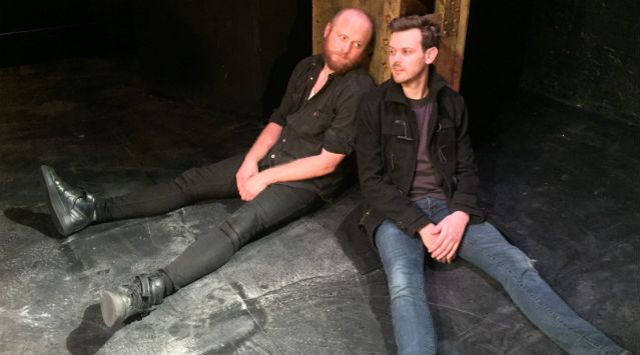

Cast: Danielle Carter, Sam O’Sullivan, Sean Taylor

Image by Clare Hawley

Theatre review

Addiction might be termed a modern phenomenon. In recent years, conditions of all kinds ranging from alcohol and drug use, to sexual and stealing behaviours, have become forms of addiction, almost achieving medical or pathological legitimacy in the general discourse of Western life. David Hare’s My Zinc Bed examines the meanings behind this contemporary way of looking at human volition and responsibility, and the quality of human weakness versus expectations regarding the individual’s contribution or dependence on society. The script is extremely contemplative, punctuated by stimulating and controversial ideas that can be challenging, although the tone of the work is notably gentle and compassionate. We are encouraged to examine the human condition from a refreshing perspective and to evaluate our assumptions about addictions of different kinds, but always being mindful about the vulnerabilities that we share.

Mark Kilmurry’s direction is interested in all the philosophical content of the text, and succeeds in making his play a relentlessly thoughtful one, while maintaining a dramatic tension that keeps us engaged throughout. Characters in the play are not particularly likeable, but their experiences are readily identifiable, and Kilmurry ensures that their exchanges never fail to fascinate. Visual elements are effectively minimal, but subtle design flourishes are executed with remarkable elegance. Tobhiyah Stone Feller’s set and Nicholas Higgins lights provide the illusion of emptiness, but provide immense scope for sentimental fluctuations. What appears to be cold and hard on the surface, is actually quite subconsciously moving with each transition of scenes.

There are breathtaking performances to be found in the production. All three actors demonstrate a thorough understanding of text and characters, and their interactions are consistently powerful. Every line is delivered with the sizzle of subtext and mystery, and we are seduced into worlds of imagination and reflection. The rhapsodic Sean Taylor is as magnetic as he is convincing. We are lured into studying his every minute gesture, believing them to be of great significance, and his commanding voice is simply irresistible. The actor’s presence is an overwhelming one, and it is fortuitous that his abilities at storytelling are no less impressive. Danielle Carter’s part requires her to display extraordinary inner complexity and also to portray the somewhat customary femme fatale with a forceful allure, both of which she performs with tremendous impact. The central Paul Peplow is played by Sam O’Sullivan, who brings earnestness, passion and emotional intensity to a personality that is more than familiar to many of our lives. His work feels genuine, and the believability of his creation is crucial to the show’s success.

Being social means that we rely on each other. Every person is both strong and weak, and there is a constant negotiation that happens in how much we are willing to forgive, how we apportion blame, and how far we can extend kindness. Paradigms of illness and disease demand of us generosity, but like anything social, they stand to be exploited in ways that will not always find universal agreement. Addiction is real, but also false. Like any label of identification, it provides an indication of circumstances, that must always be prepared to be questioned.

Venue: Hayes Theatre Co (Potts Point NSW), Oct 8 – Nov 1, 2015

Venue: Hayes Theatre Co (Potts Point NSW), Oct 8 – Nov 1, 2015 Venue: King Street Theatre (Newtown NSW), Oct 13, 2015

Venue: King Street Theatre (Newtown NSW), Oct 13, 2015 Venue: The Depot Theatre (Marrickville NSW), Oct 7 – 24, 2015

Venue: The Depot Theatre (Marrickville NSW), Oct 7 – 24, 2015 Venue: New Theatre (Newtown NSW), Oct 6 – Nov 7, 2015

Venue: New Theatre (Newtown NSW), Oct 6 – Nov 7, 2015 Venue: King Street Theatre (Newtown NSW), Oct 6 – 24, 2015

Venue: King Street Theatre (Newtown NSW), Oct 6 – 24, 2015 Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Oct 1 – 17, 2015

Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Oct 1 – 17, 2015 Venue: Bon Marche Studio (Ultimo NSW), Oct 1 – 4, 2015

Venue: Bon Marche Studio (Ultimo NSW), Oct 1 – 4, 2015 Venue: Blood Moon Theatre (Potts Point NSW), Sep 29 – Oct 17, 2015

Venue: Blood Moon Theatre (Potts Point NSW), Sep 29 – Oct 17, 2015 Venue: Old Fitzroy Theatre (Woolloomooloo NSW), Sep 29 – Oct 10, 2015

Venue: Old Fitzroy Theatre (Woolloomooloo NSW), Sep 29 – Oct 10, 2015