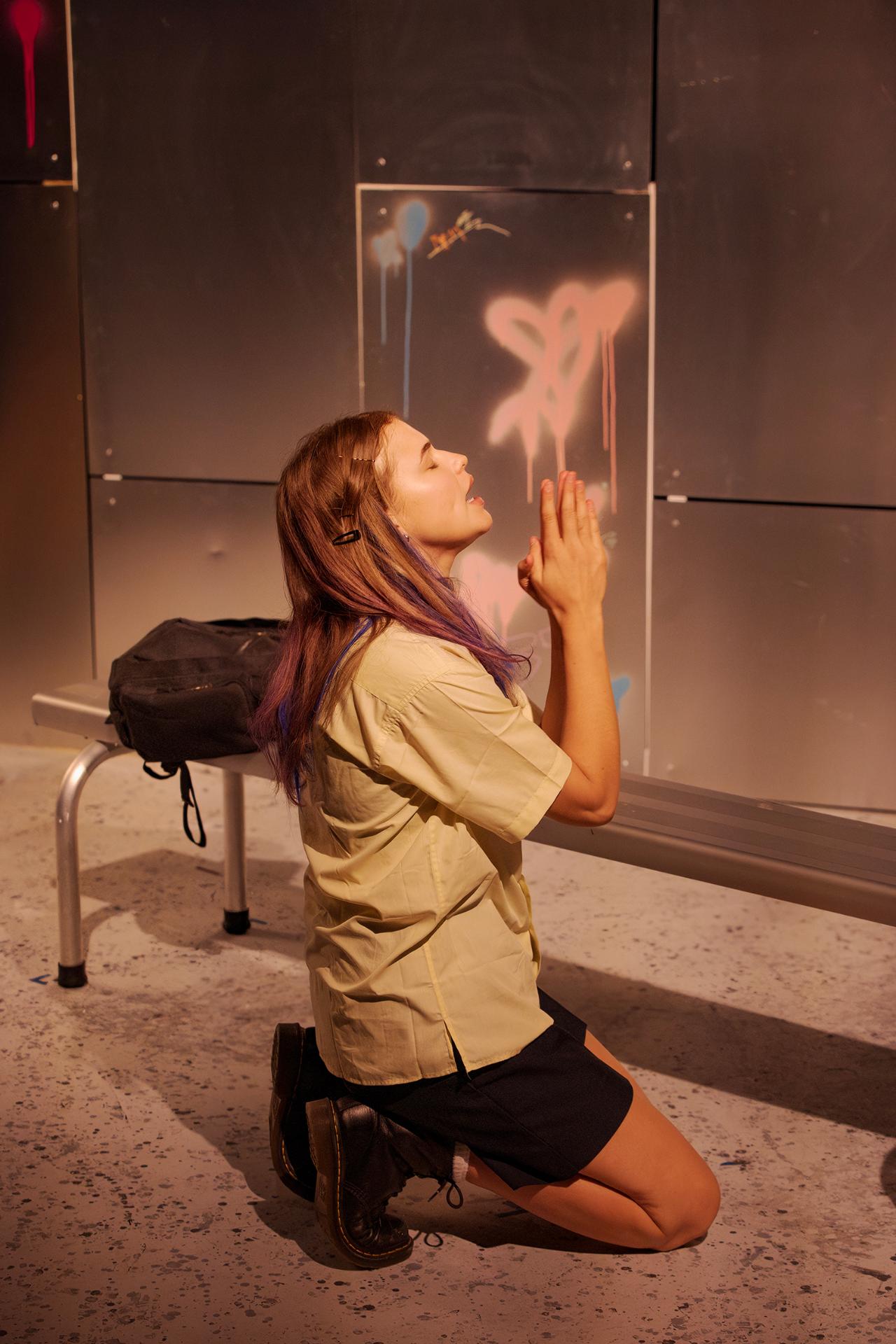

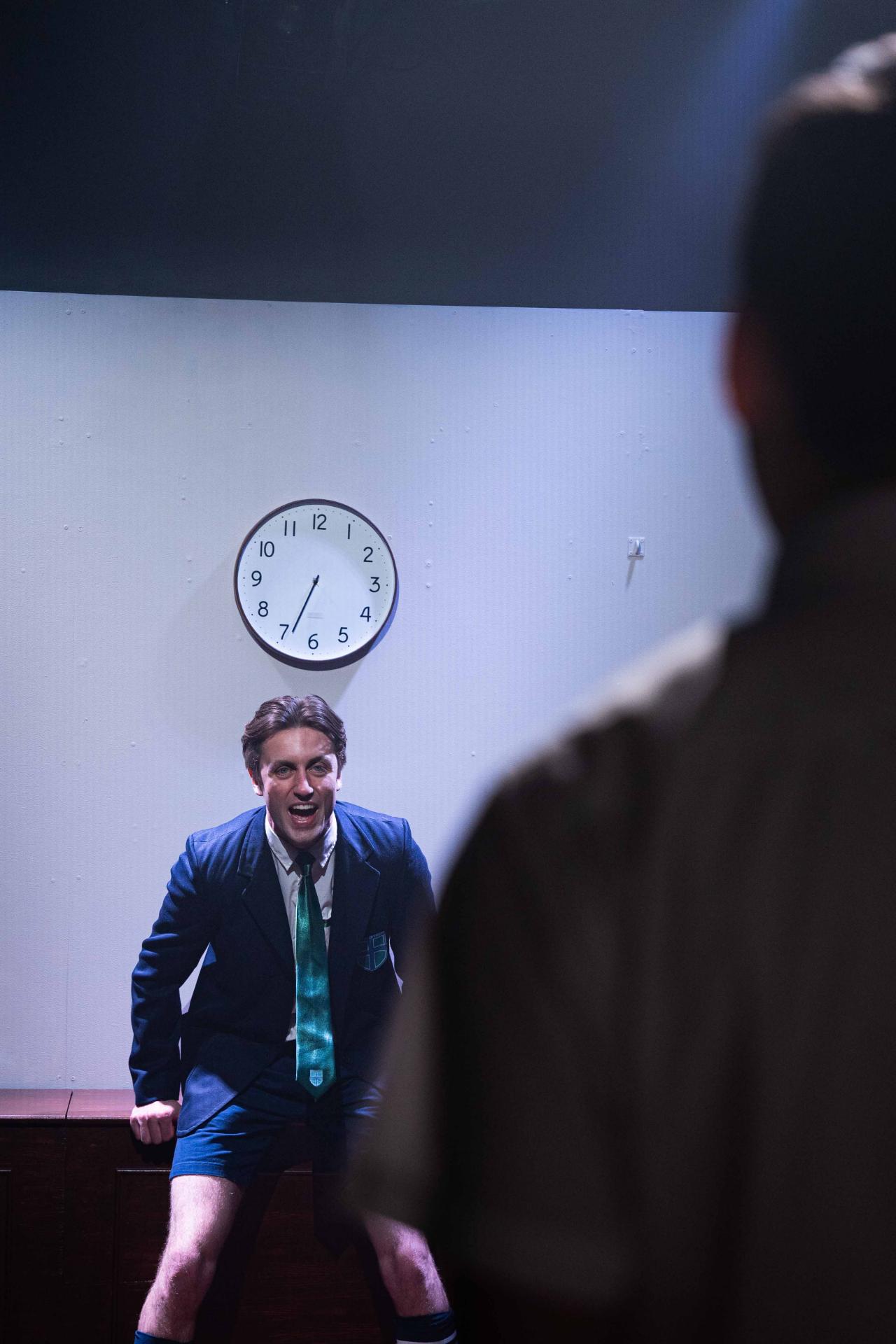

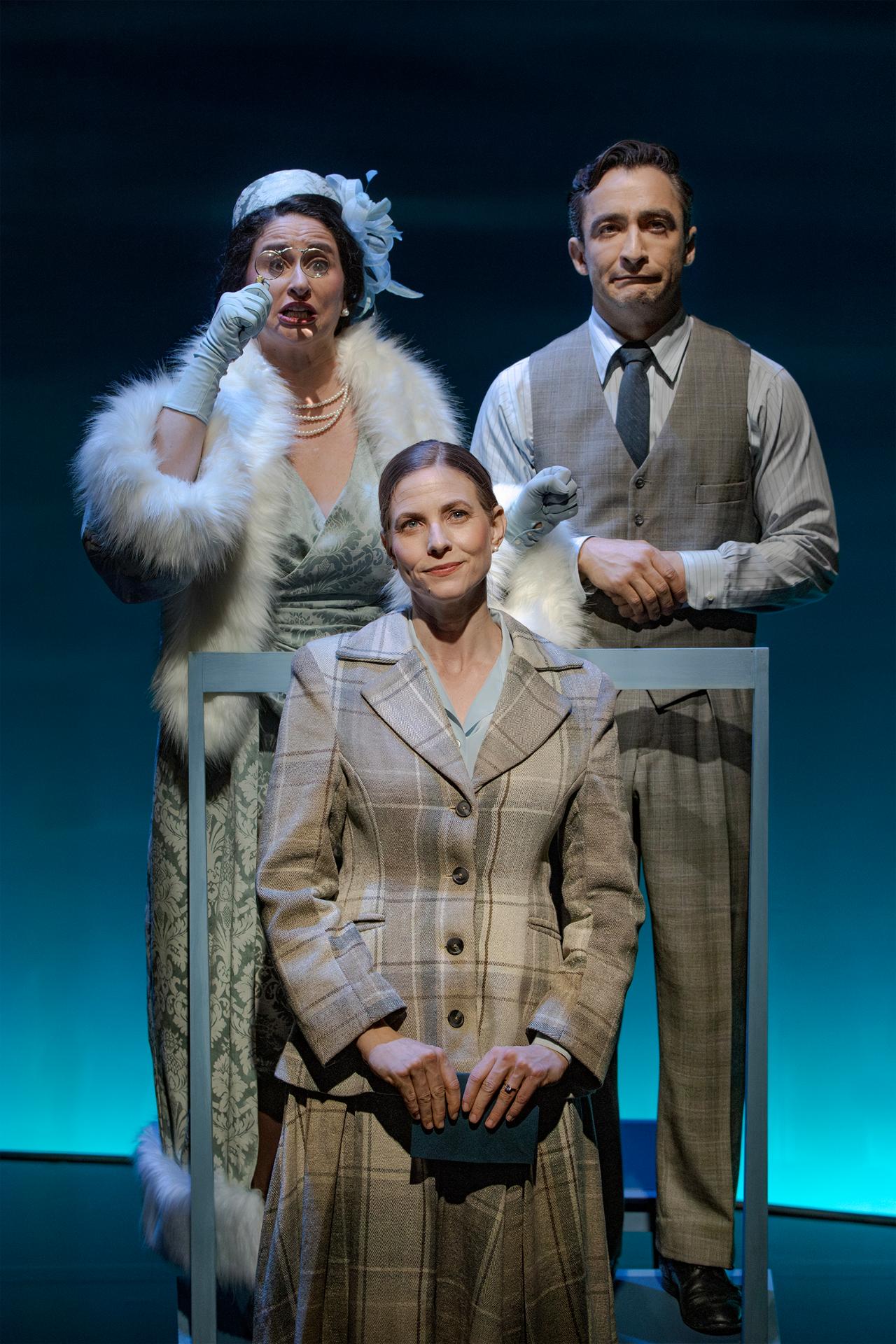

Venue: Old Fitzroy Theatre (Woolloomooloo NSW)

Sitting, Screaming Sep 20 – Oct 5, 2024

Playwright: Madelaine Nunn

Director: Lucy Clements

Cast: Clare Hughes

Images by Phil Erbacher

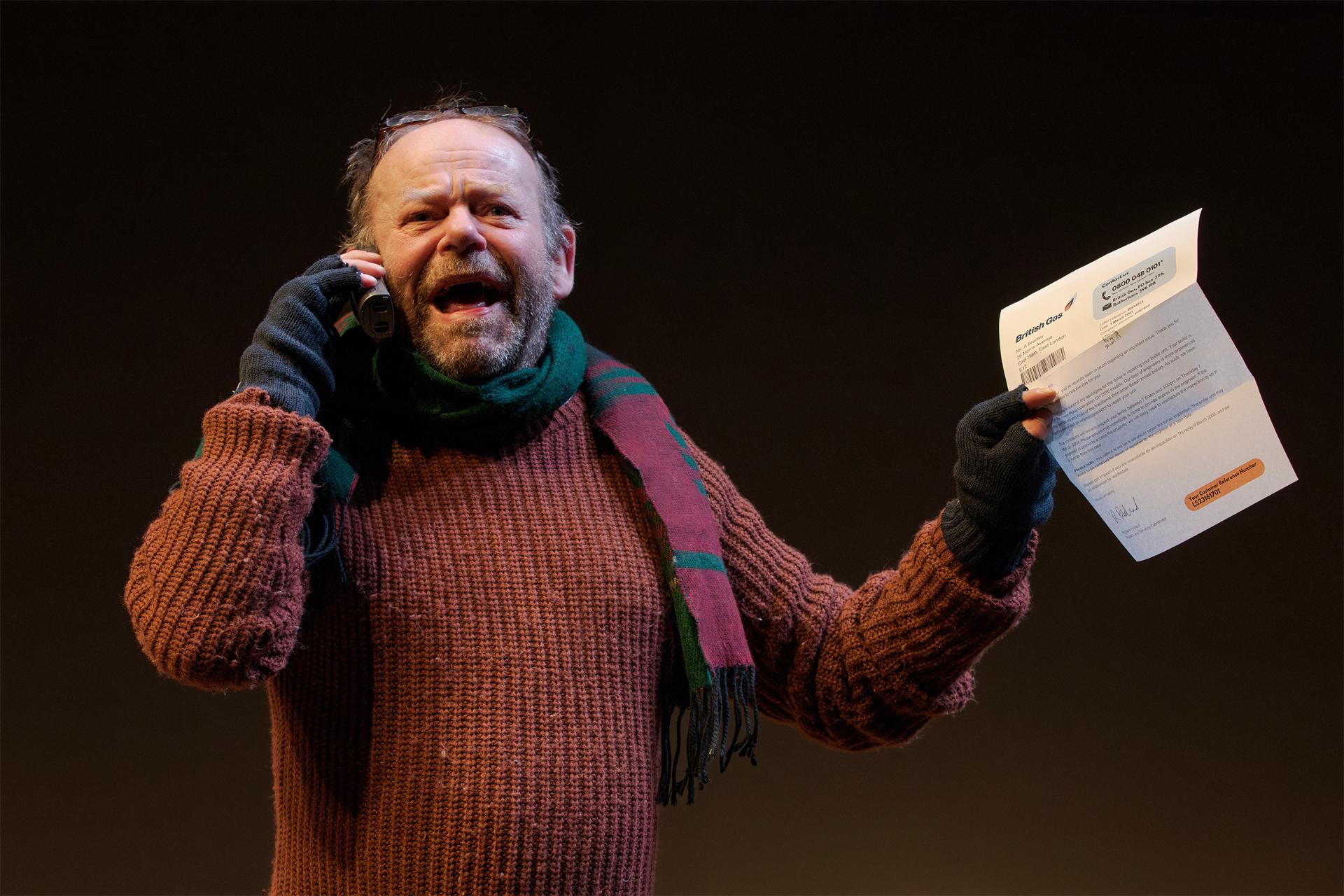

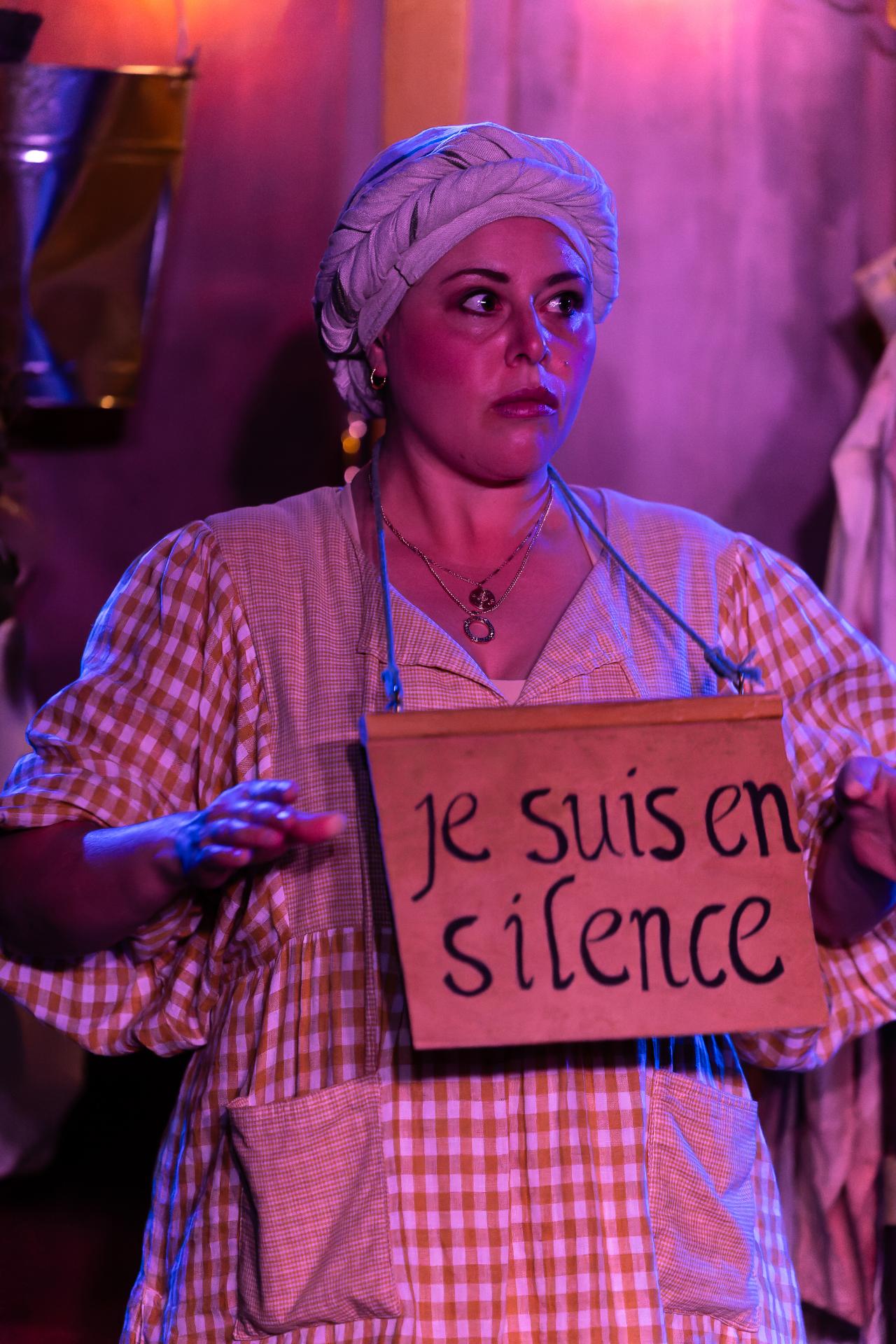

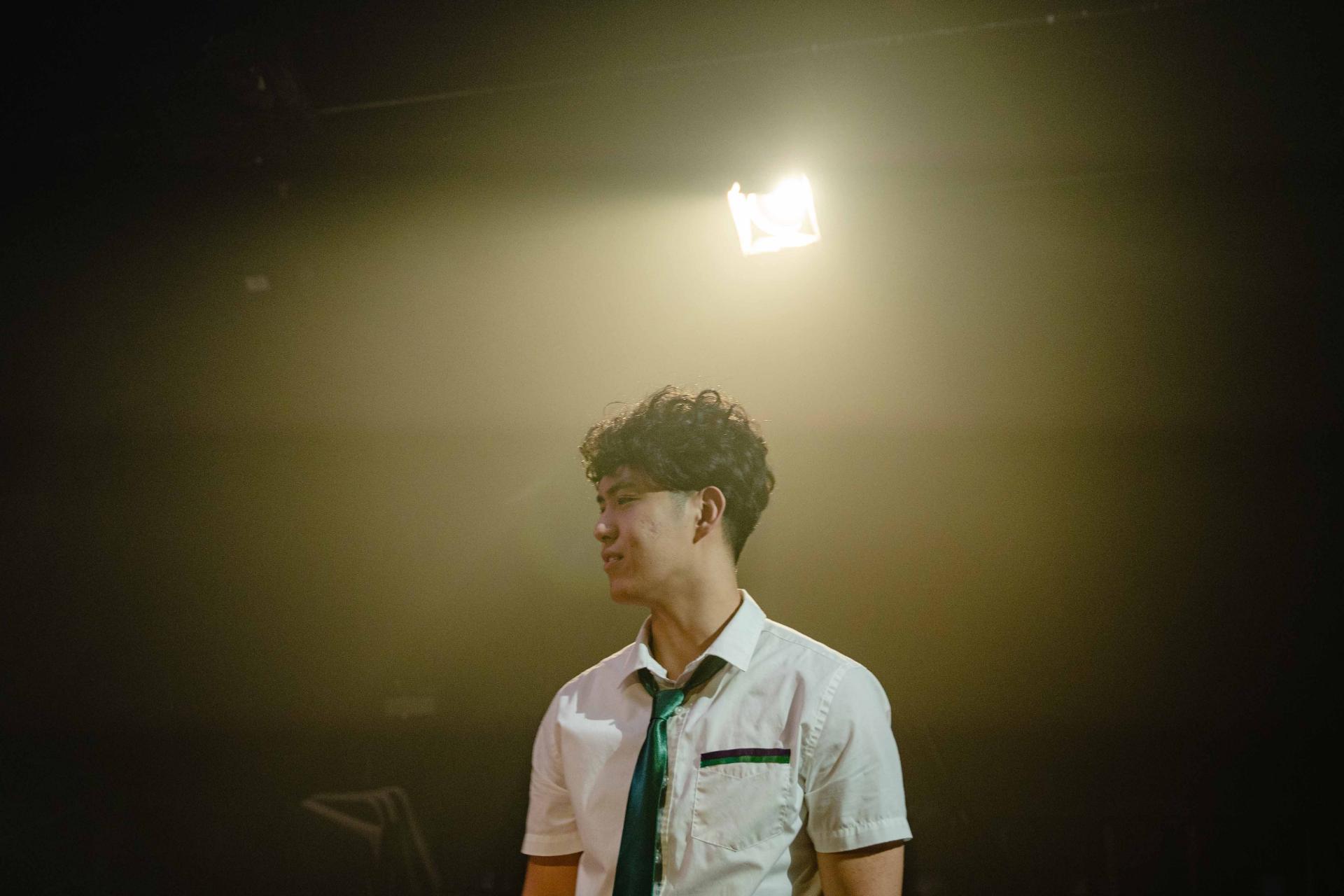

Anomalies Sep 20 – Oct 5

Playwright: Jordyn Fulcher

Director: Matt Bostock

Cast: Giani Fenech, Rhiaan Marquez, Harold Phipps

Images by Phil Erbacher

Theatre review

Centred in the second instalment of New Works Festival by Old Fitz Theatre, are the troubling lives of teenagers. Madelaine Nunn’s Sitting, Screaming depicts with searing realism the dangerous situation of a schoolgirl dealing with a predator, whilst Jordyn Fulcher’s Anomalies is completely fantastical in its speculations about a dystopian future, when three youngsters find themselves waking up to calamity, as an extensive technological malfunction takes hold.

The very cleverly structured and rigorously considered Sitting, Screaming is a work of gripping theatre, as directed by Lucy Clements, who brings exceptional detail to this exploration of rape culture. Its protagonist Sam is played by the wonderful Clare Hughes, who keeps us riveted for the entirety, highly impressive with the tonal variations she introduces, for an occasion of memorable storytelling.

Anomalies however is much more demanding of its audience. Although given energetic direction by Matt Bostock, the piece speaks in a convoluted and alienating language, over a lengthy duration, and with little narrative development. The cast works hard to make sense of the play, but Giani Fenech, Rhiaan Marquez and Harold Phipps can only be credited for being able to find meaning from Anomalies for themselves.

Thankfully, we discover that the staging for both are remarkably well designed. Hailley Hunt’s set and costumes are expressive, and convincing with what they wish to convey. Lights by Luna Ng are commendable for their attentiveness to the nuances of the writing, and for helping us shift through all the vacillating drama and comedy. Sounds by Sam Cheng for Sitting, Screaming too are effective at pulling us deep into the fluctuating emotional textures, just as Milo McLaughlin’s audio creations for Anomalies are able to indicate the escalating intensity of its sci-fi predicament.

Characters in both tales, one authentic and one imaginary, inherit broken worlds. So much of what is normalised, should never have been deemed acceptable. It is through the perspective of youth that we can clearly see that all we have acquiesced to consider good enough, is actually of tragic proportions. The eternal dilemma of humanity seems to be that we cannot help but conceive of perfection, but to bring it to fruition is always beyond us.

ww.oldfitztheatre.com.au | www.newghoststheatre.com