Venue: Old Fitzroy Theatre (Woolloomooloo NSW), Nov 28 – Dec 14, 2025

Playwright: Jack Kearney

Director: Lucy Clements

Cast: Deborah Galanos, James Lugton, Owen Hasluck, Sharon Millerchip, Sofia Nolan

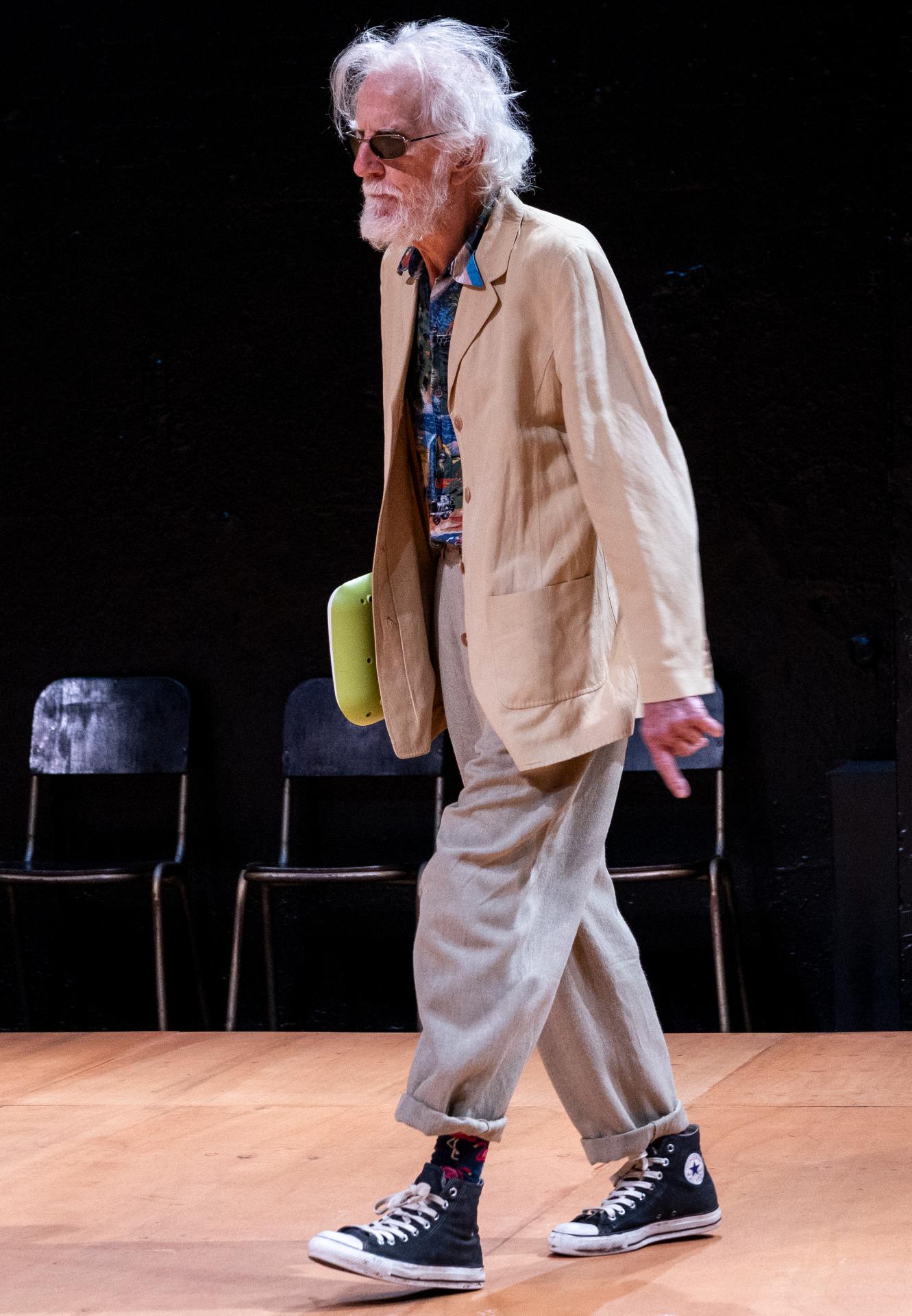

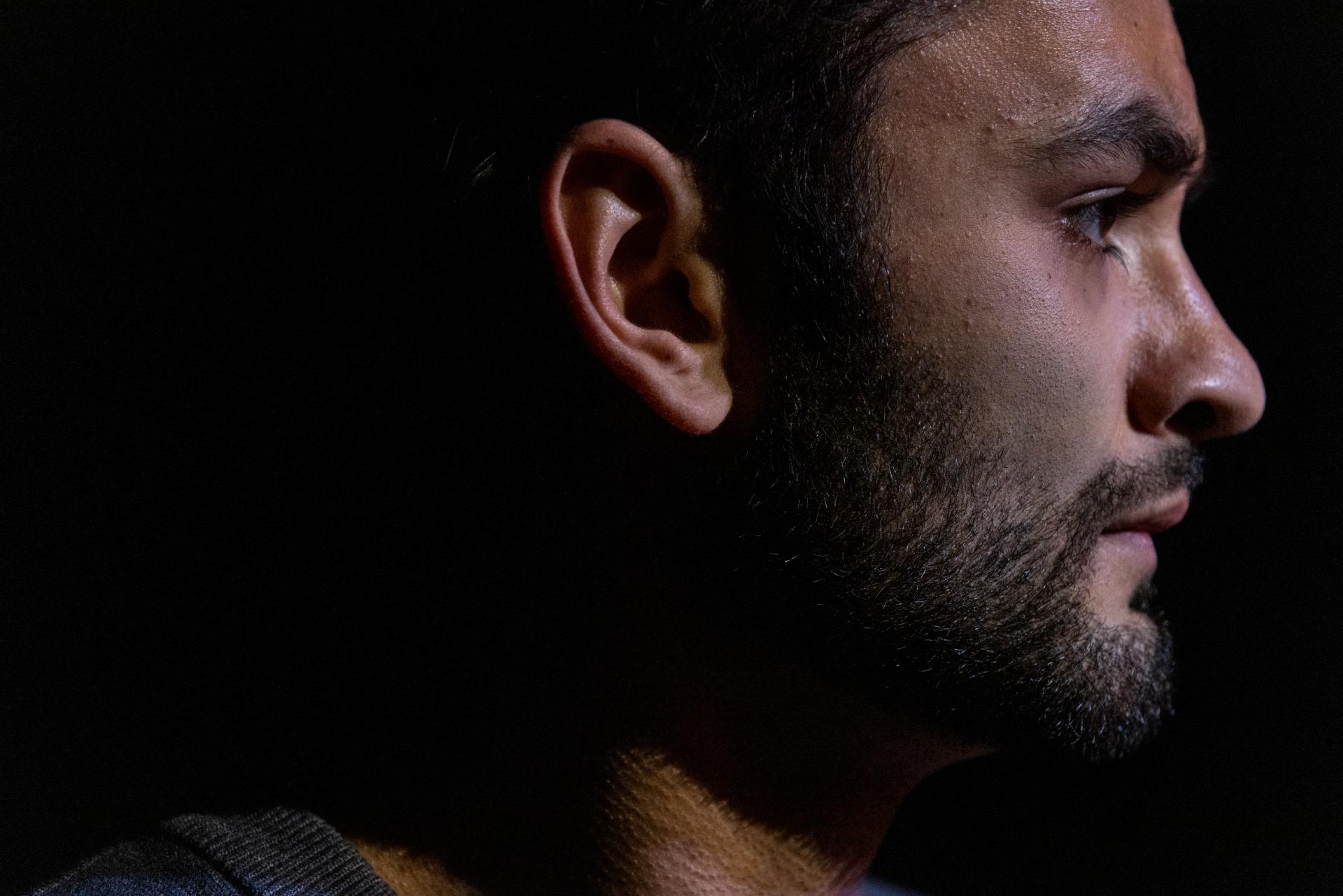

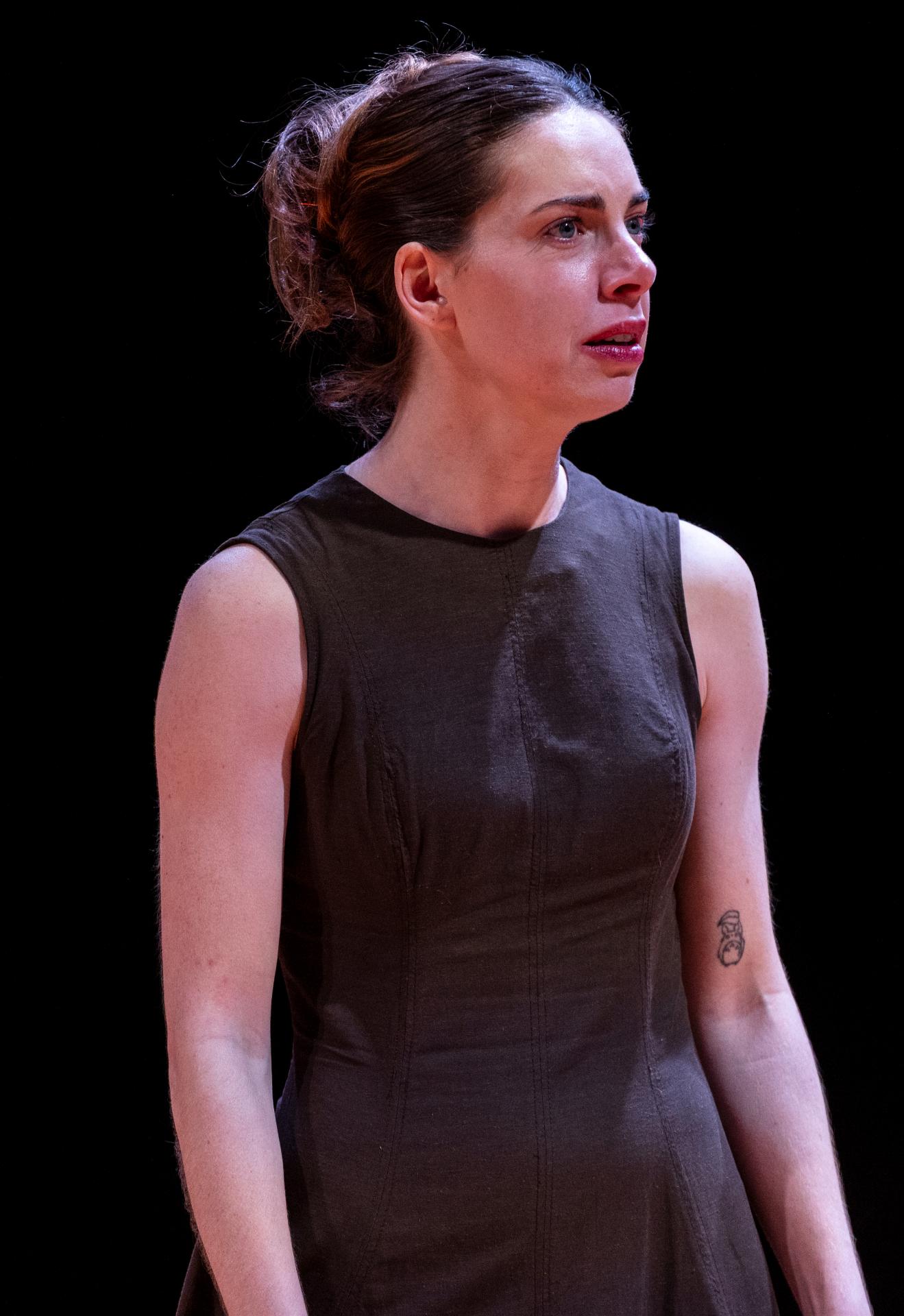

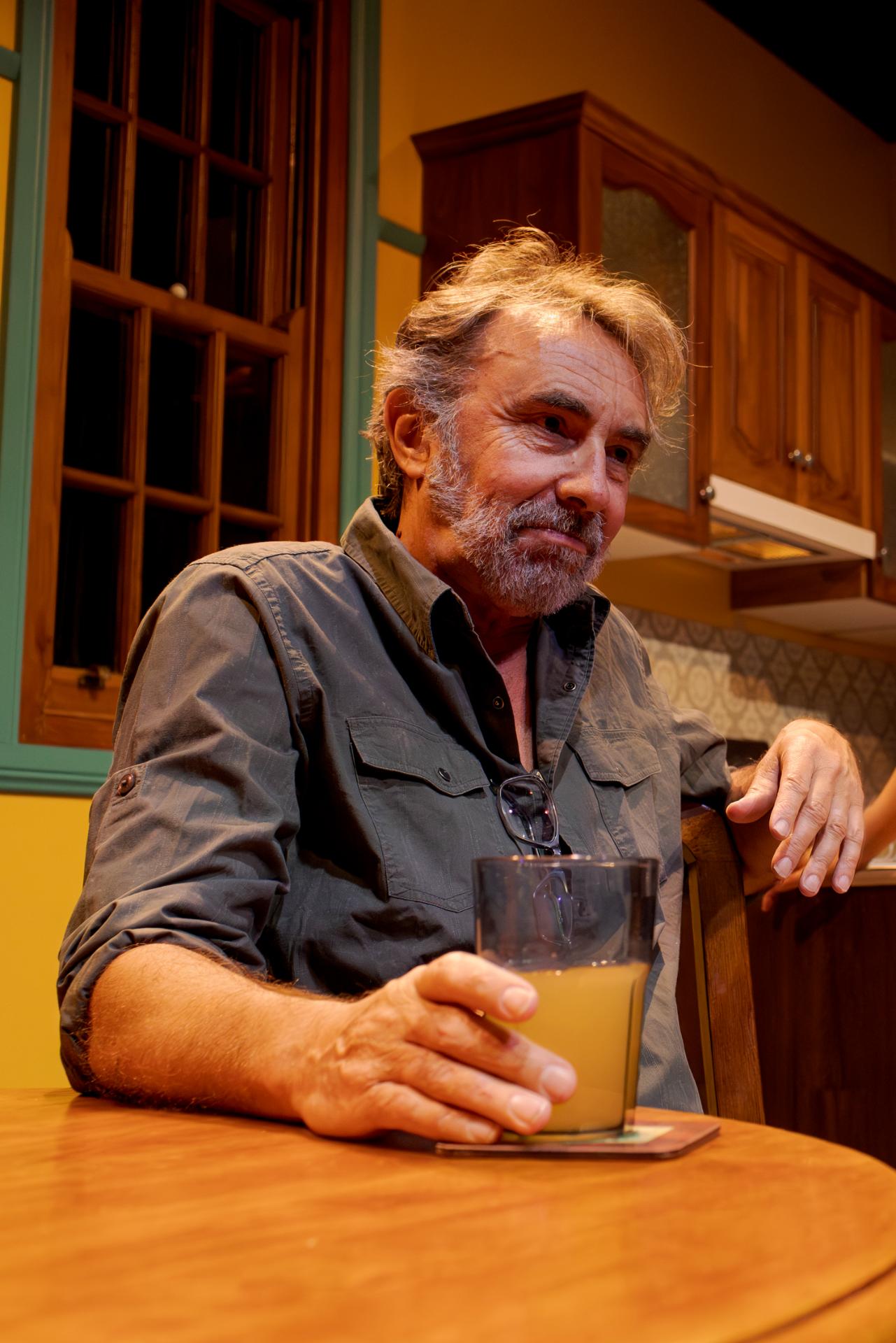

Images by Phil Erbacher

Theatre review

April returns to her family home in Western Sydney after several years in Denmark, only to find that the landscape she left behind has shifted in ways no one is willing—or equipped—to articulate. In Jack Kearney’s Born on a Tuesday, the family’s chronic ineloquence becomes a kind of endurance test: months pass, crises mount, yet they orbit around their wounds with quiet desperation, unable to summon the intimacy or vulnerability required for meaningful connection. The result is a drama in which very little seems to occur, and although it captures certain truths about Australian parochialism, the writing rarely deepens those insights into a fully satisfying theatrical experience.

Lucy Clements’ direction lends the production an unmistakable gravity, keeping us attuned to the persistent despondency saturating April’s household, but that solemnity never quite translates into emotional engagement. These characters are not unsympathetic, yet we are seldom invited far enough into their inner lives to feel invested in their journeys.

The performances, however, are uniformly strong. Sharon Millerchip, as April’s mother Ingrid, delivers an impressively layered portrayal, marked by meticulous detail and a striking naturalism. Sofia Nolan’s April is earnest and committed, though the evasive quality of the writing often constrains her. Owen Hasluck brings a welcome charisma to April’s brother Isaac, while Deborah Galanos and James Lugton infuse their neighbour characters with a vividness and vitality that guard the piece from tipping entirely into gloom.