Venue: Flight Path Theatre (Marrickville NSW), Feb 5 – 15, 2025

Playwright: Anton Chekhov (adapted by Victor Kalka)

Director: Victor Kalka

Cast: Matthew Abotomey, Meg Bennetts, Alex Bryant-Smith, Nicola Denton, Barry French, Sarah Greenwood, Jessie Lancaster, Alice Livingstone, Ciaran O’Riordan, Mason Phoumirath, Joseph Tanti

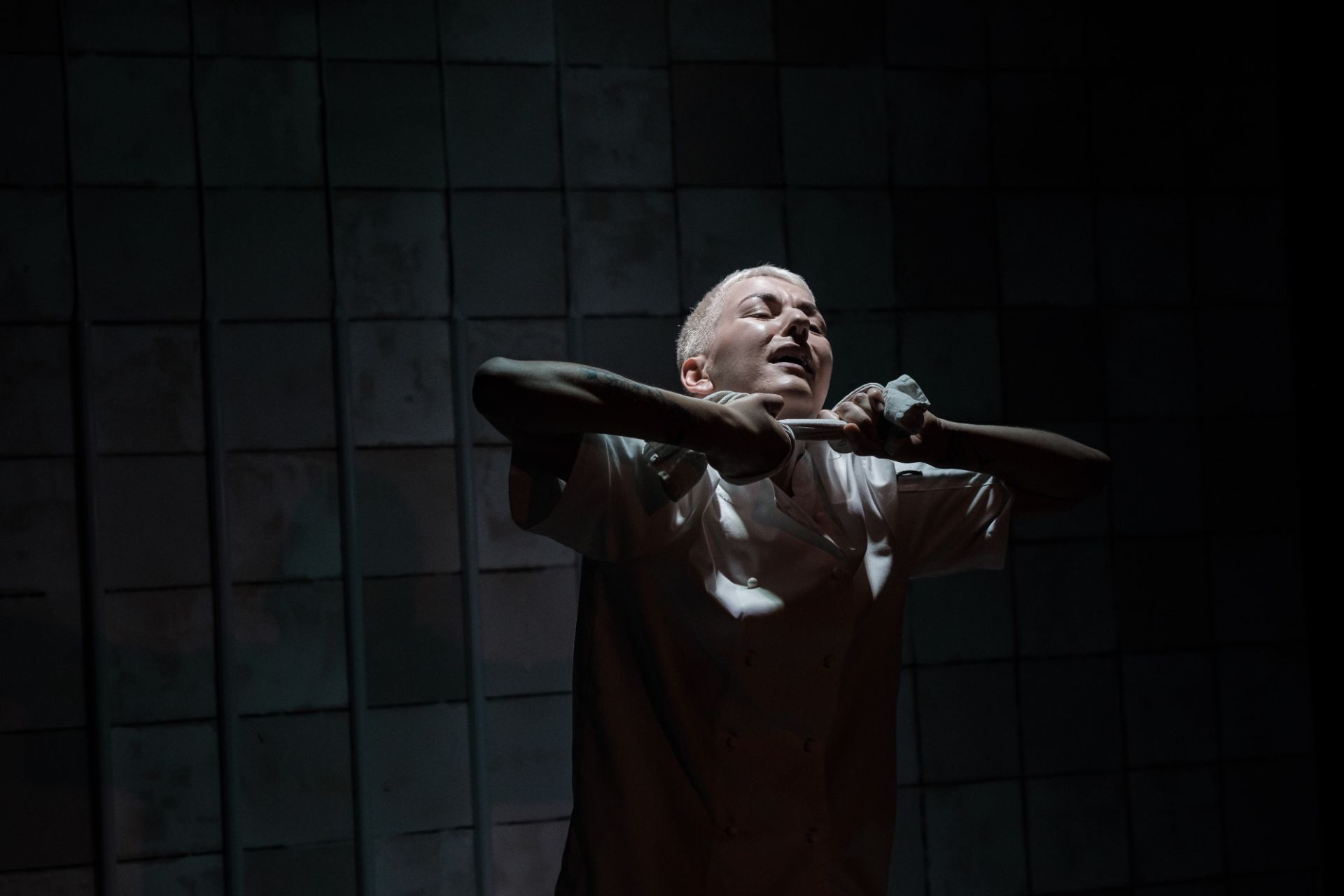

Images by Samuel Webster

Theatre review

It is becoming increasingly odd to see characters in Chekhov’s Three Sisters talk about “work” like it is something optional. The notion of nobility has faded so far from popular consciousness, that any alternative to a life of work, is now proving unimaginable. In this adaptation by Victor Kalka, we may not be able to relate much to the lifestyles of these Russians from the year 1900, but it seems that Chekhov’s representations of existential angst can still resonate.

This is a version that, at just over 100 minutes, should have been easily digestible, but early portions struggle to connect. The constant lamenting of a bygone era is tiresome, with characters expressing grievances that are entirely alienating. After the fire however, they are made to grapple with something more authentic, and in the concluding moments, Three Sisters comes back to life.

The cast of 11 can be lauded for establishing a uniformity in tone, even though some performers are certainly more compelling than others. Set design by Kalka thoughtfully positions entrances to the stage that facilitate smooth movement, but it is arguable if his take on modernised costuming depicts the nature of class appropriately for the story. Lights by Jasmin Borsovszky bring elegance to the presentation, along with pleasant variations to atmosphere. Sounds by Patrick Howard offer simple enhancements for a sense of theatricality.

It can be construed that the people in Three Sisters are looking for purpose, rather than literal work, in what they feel to be an aimless existence. In 2025 we are discovering that work can easily be just as unfulfilling, if not completely self-jeopardising, in this era of the oligarch’s aggressive re-emergence. In the present moment, authoritarian figures of power are demonstrating their patent disregard for our welfare as contributors to their successes, whether as consumers or as resources for production. We can still think of work as honourable, but more than ever, the understanding of what our labour is really serving, needs to come to the fore.