Venue: Roslyn Packer Theatre (Sydney NSW), Nov 21 – Dec 16, 2023

Playwright: Anton Chekhov (adapted by Andrew Upton)

Director: Imara Savage

Cast: Arka Das, Michael Denkha, Harry Greenwood, Markus Hamilton, Mabel Li, Sean O’Shea, Toby Schmitz, Sigrid Thornton, Megan Wilding, Brigid Zengeni

Images by Prudence Upton

Theatre review

Constantine’s angst remains resolute, even though he no longer lives in 1896 Russia. Andrew Upton’s adaptation of Chekhov’s The Seagull takes place in current day Australia, refreshed with modernised dialogue that effervesces amusingly, but is otherwise entirely faithful to the original. It is arguable whether these characters would think and behave the same, having moved continents and centuries. Even though human nature can be disconcertingly rigid, the dramatic (and iconic) conclusion of Chekhov’s play, feels too characteristic perhaps of an olden Russia. It is however certainly possible that that despondence is in fact no different, wherever and whenever the story takes place. Upton could be making the point, that we are in fact deluded, should we consider ourselves evolved and improved.

Nevertheless, the update feels somewhat tenuous, even though the contemporarised humour of the piece is an unequivocal pleasure. Directed by Imara Savage, the show is at its most appealing when moments are drenched in irony, as we watch persons of a certain privilege, unable to evade nihilistic despair. Reflecting on Chekhov’s times, we can associate The Seagull with impending revolutions, and explain that malaise within a context of disquietude and a thirst for upheaval. Watching the same tale unfold in our here and now, is a confronting proposition. That unflinching pessimism could be saying something appalling about the people we are, or we could simply regard this transposition to be somehow inauthentic.

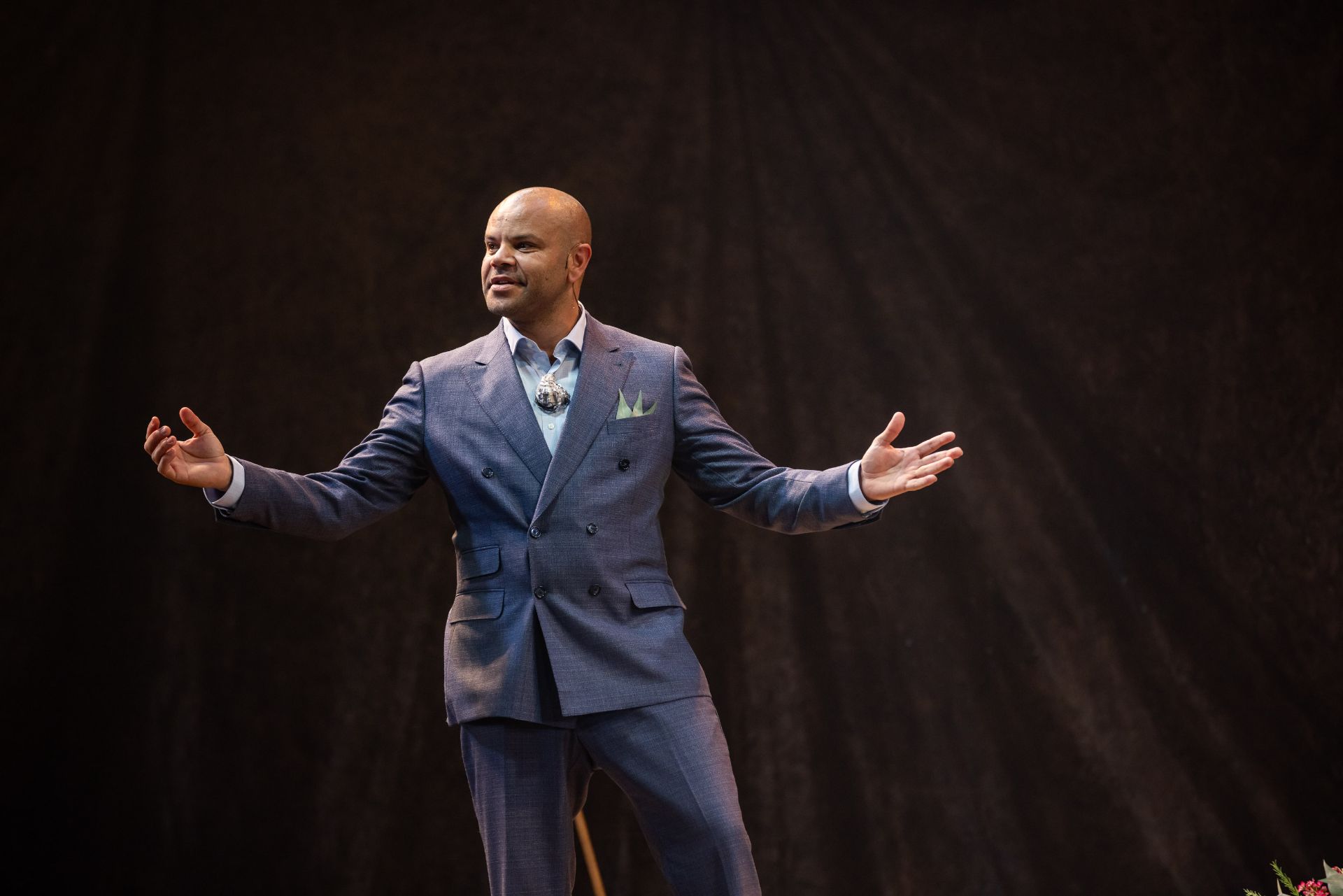

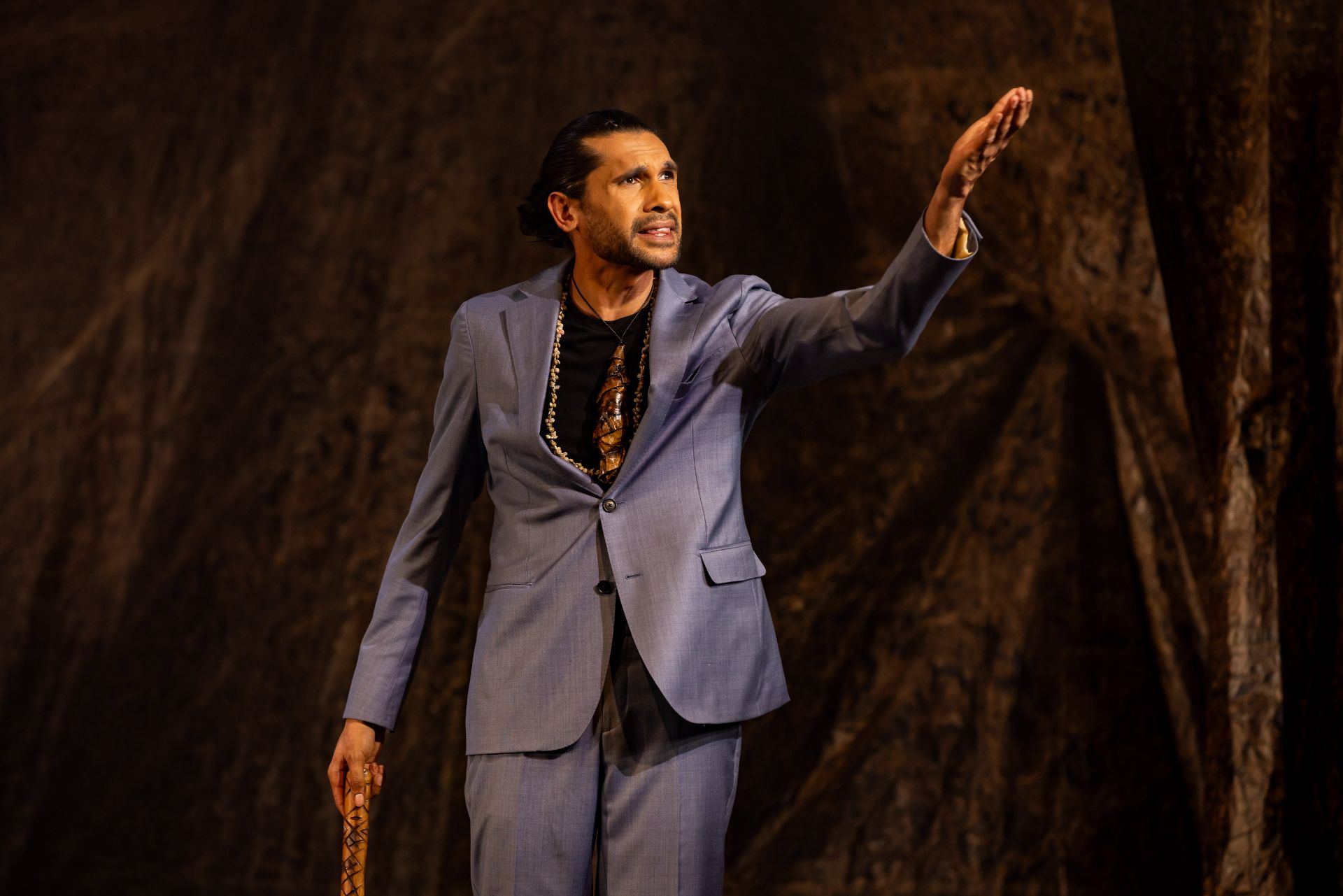

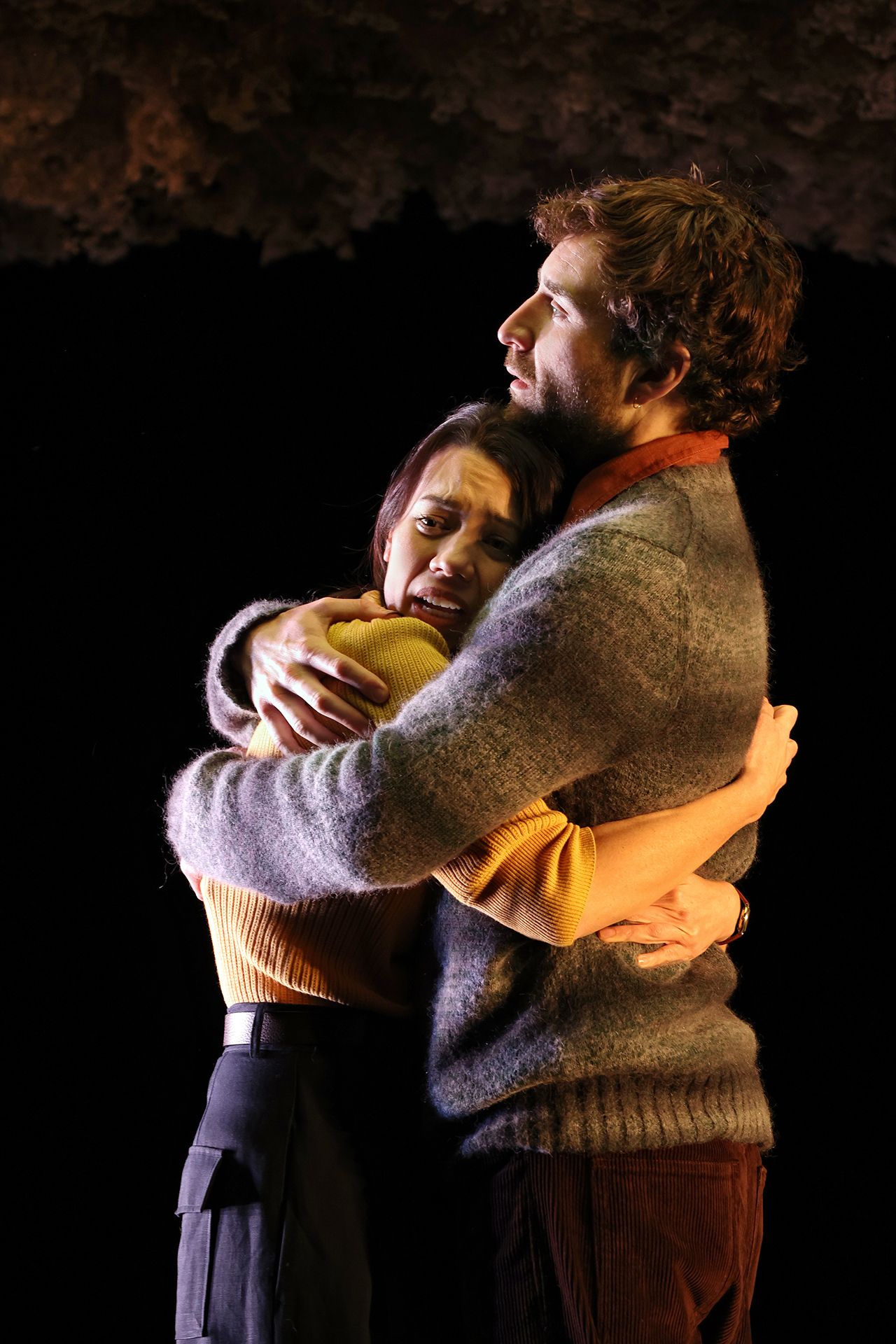

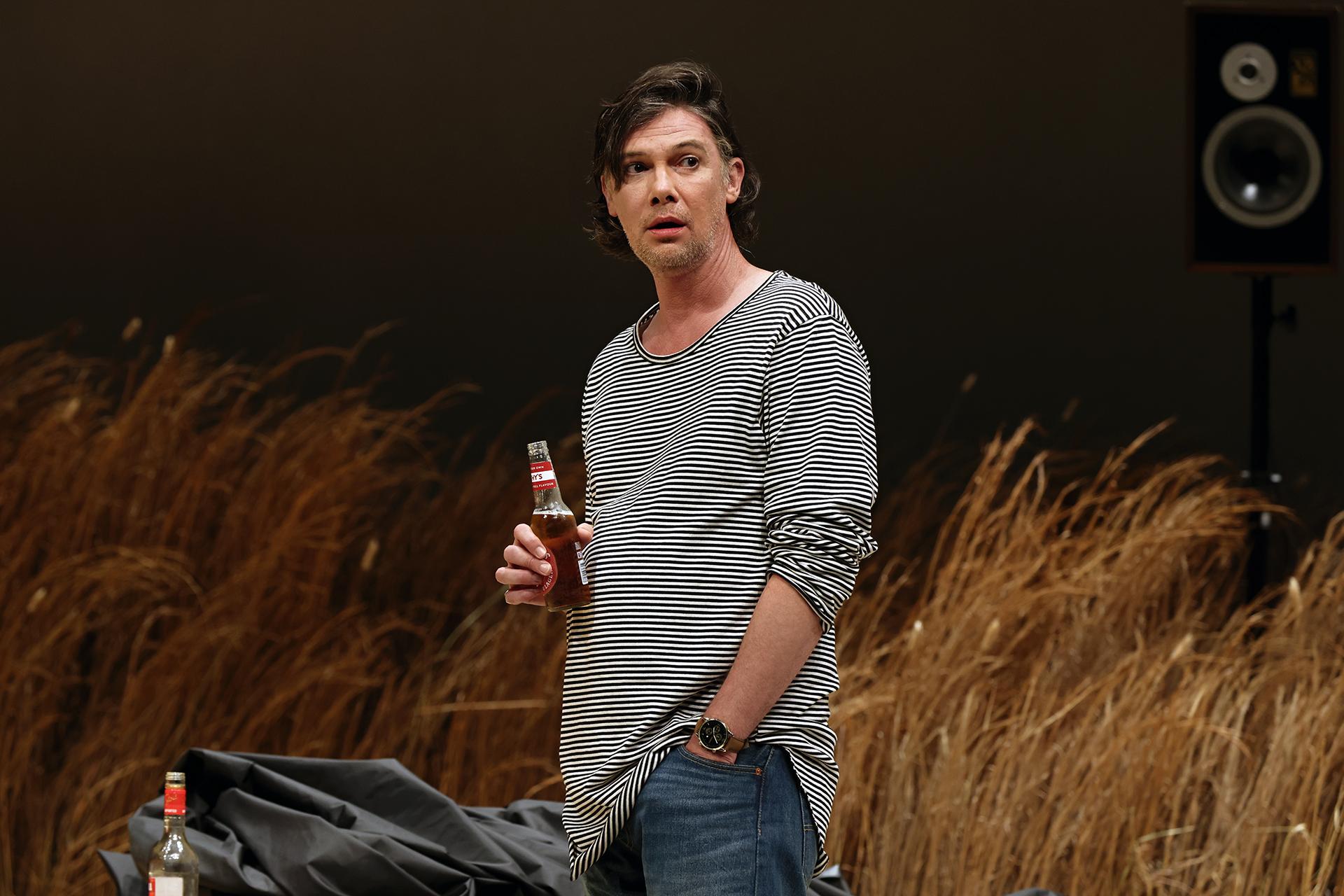

All the same, drama is delicious. Actor Harry Greenwood as Constantine is less sympathetic than is traditionally portrayed, but renders an unassailable sense of truth and integrity, to persuade us of his narrative. Other notable performers include Mabel Li, equally impressive in comedic and tragic portions of Nina’s exploits, able to make convincing the drastic shift in temperaments, for this classic showcase of lost innocence. Sean O’Shea’s highly idiosyncratic turn as Peter proves thoroughly delightful, very extravagant in style but unquestionably charming with his interpretations of an ageing invertebrate. Playing Boris the cad is Toby Schmitz, wonderfully inventive and unpredictable, in his thrilling explorations of self-absorption and immorality. On stage, Schmitz’s impulsiveness is a real joy.

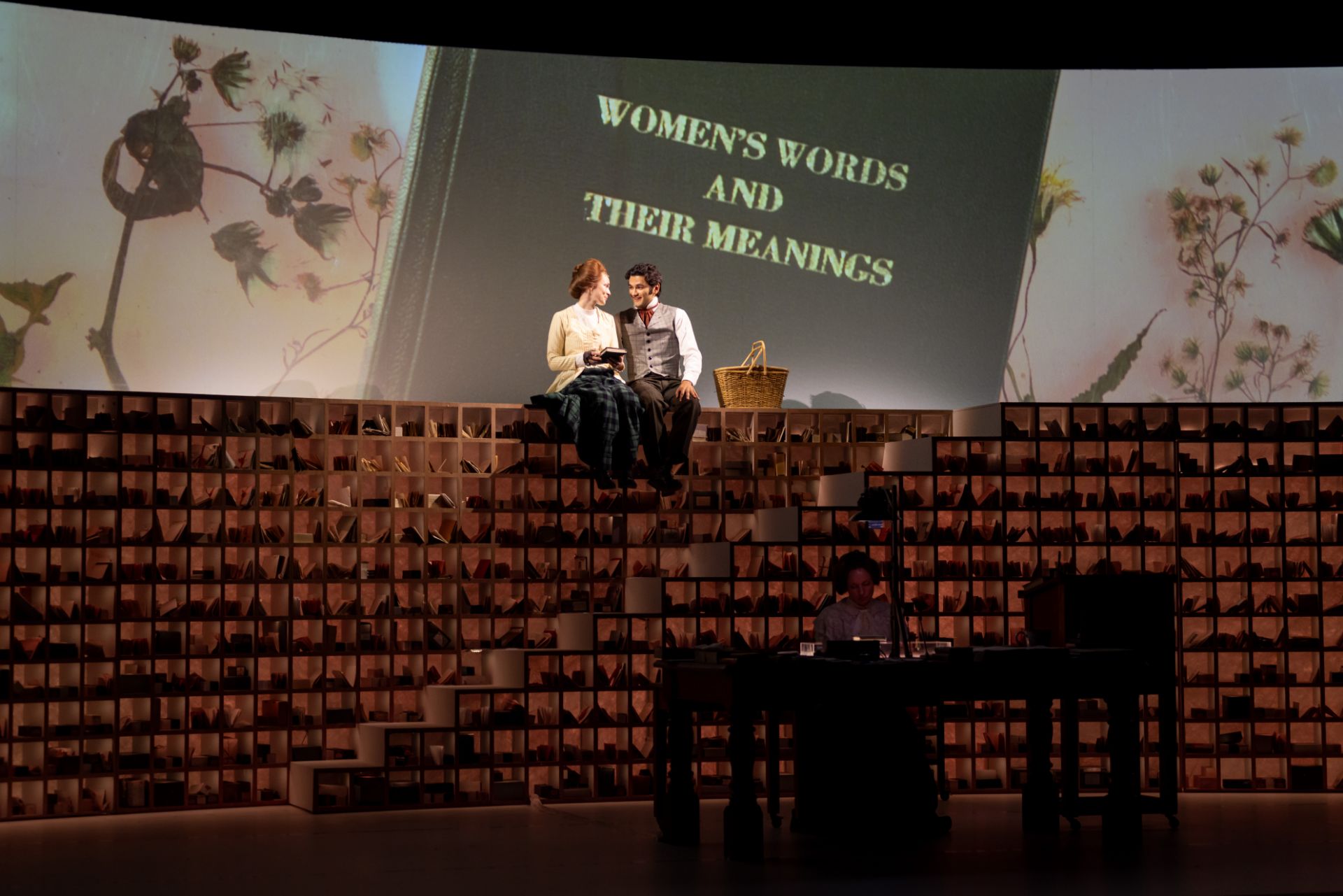

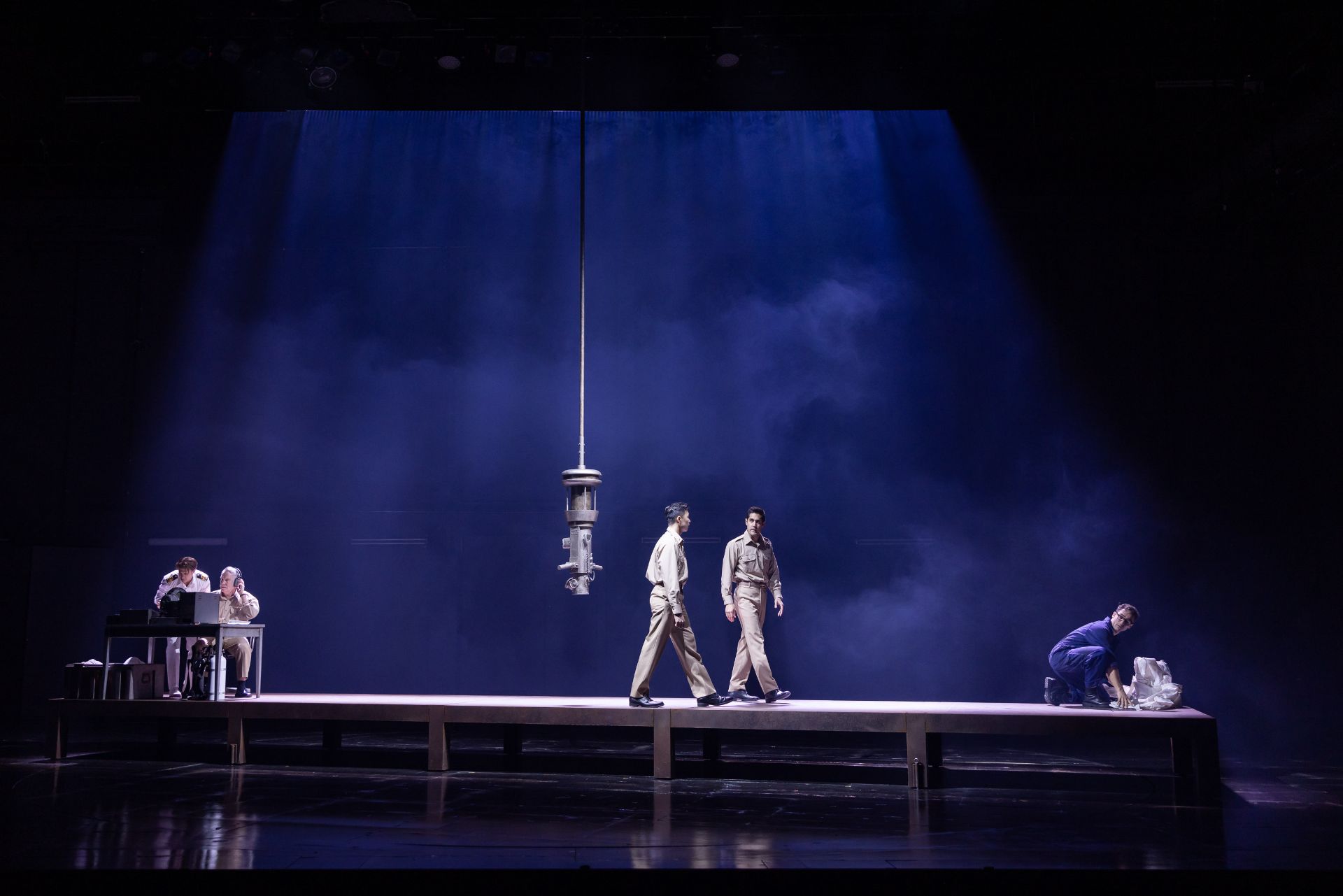

Set design by David Fleischer conveys a rustic sensibility, but always with a quiet sophistication that reminds us of the social class being depicted. Costumes by Renée Mulder emphasise the modernity of characters, keeping them accurately within the current generation. Lights by Amelia Lever-Davidson, along with sounds and music by Max Lyandvert, are extremely subtle until the final climactic scenes, when we are treated to a greater theatricality, as the show approaches its inevitable melodramatic conclusion.

The world tells Constantine that by virtue of his biological and social distinctions, that he is destined to be a leader and a winner. In the microcosm of his daily existence however, he only feels belittled and disgraced. Males account for three-quarters of suicide in Australia today. We can diverge in our understandings of that statistic, but it is a clearly a question of gender that cannot be ignored. We are all vulnerable beings. It is the quixotic notion that some of us have to be impervious to human fallibilities, that can drive a person to the brink.