Venue: Hayes Theatre Co (Potts Point NSW), Sep 5 – Oct 5, 2025

Music, Book & Story: Steve Martin

Music, Lyrics & Story: Edie Brickell

Directors: Miranda Middleton, Damien Ryan

Cast: Cameron Bajraktarevic-Hayward, Kaya Byrne, Victoria Falconer, Genevieve Goldman, Jack Green, Deirdre Khoo, Hannah McInerney, Jarrad Payne, Rupert Reid, Katrina Retallick, Felix Staas, Alec Steedman, Molly Margaret Stewart, Olivia Tajer, Seán van Doornum

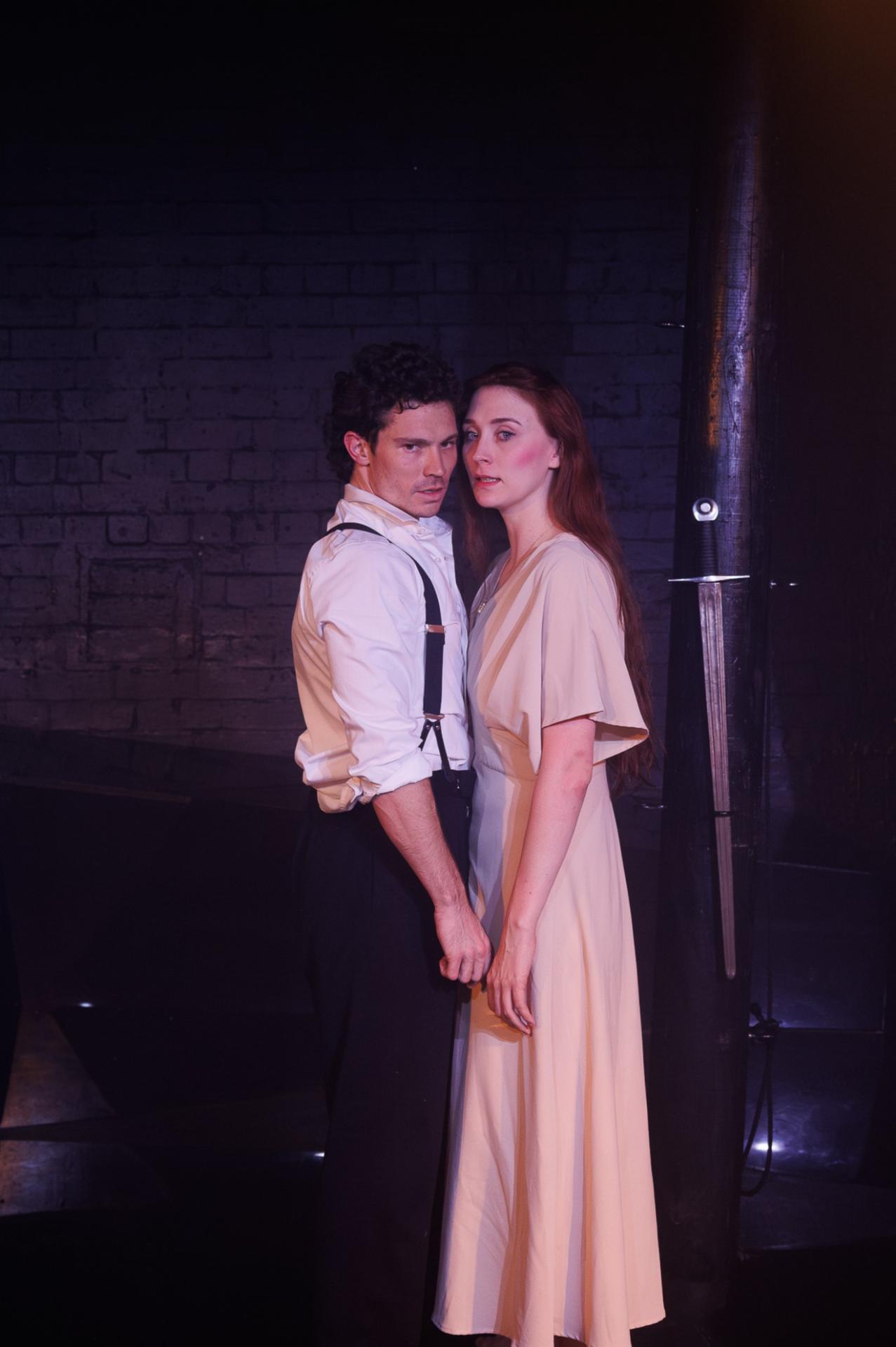

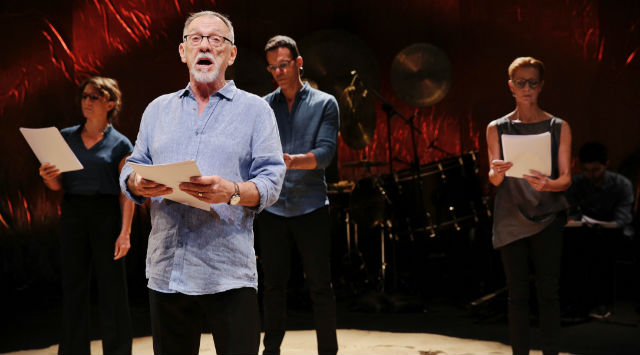

Images by Robert Catto

Theatre review

The story begins a century ago in North Carolina, where Alice falls pregnant out of wedlock and is forced to give up her child. At a time when single motherhood was considered unthinkable, women who defied convention by seeking independence or family without a husband were often subjected to severe persecution. Bright Star, the musical by Steve Martin and Edie Brickell, revisits this not-so-distant chapter of history, exposing the harsh, often barbaric conditions faced by some Americans. While the narrative tends to be too obviously tugging at our emotions, the production is buoyed by its irresistibly vibrant score, written in the bluegrass tradition, which remains a joy to experience.

Alec Steedman’s musical direction sweeps us into the romance and effervescence of every song, while co-directors Miranda Middleton and Damien Ryan shape the production into something strikingly elegant, imbued with warmth and empathy, even if the story’s separate timelines are not always clear. The design elements are handled with equal finesse: Isabel Hudson’s set exudes rustic charm yet retains a crisp sense of polish; Lily Matelian’s costumes evoke the American South with convincing detail, though they falter in ageing characters convincingly as the story shifts through time. James Wallis’ lighting is a continual delight—sumptuous, evocative, and unfailingly theatrical.

Hannah McInerney is commanding in the lead role of Alice, bringing remarkable depth and authenticity to the character, even if the distinction between her younger and older selves is not always sharply drawn. The two men in Alice’s life, played by Kaya Byrne and Cameron Bajraktarevic-Hayward, make a lasting impression with performances marked by sincerity, grounded realism, and an appealing lack of artifice. Also deserving mention are Deidre Khoo, Genevieve Goldman, and Jack Green, who, though in smaller roles, provide delightful flashes of humour and personality, their quirky characterisations and impeccable comic timing adding much to the production’s charm.

Not all storytelling lies in what is said, but in how it is told, and Bright Star is a case in point. The way its elements are assembled gives the production a resonance far greater than the sum of its parts. The meticulous musicianship, the generosity of its performers, and the discerning artistry of its designers coalesce to create a show that is consistently engaging, even when the plot itself borders on cliché. In this moment, we transcend the ordinary, reminded that art’s greatest gift is often the inspiration that it bestows.

Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Jan 23 – 27, 2019

Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Jan 23 – 27, 2019

Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Oct 11 – 27, 2018

Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Oct 11 – 27, 2018

Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Aug 9 – 25, 2018

Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Aug 9 – 25, 2018

Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Oct 12 – 28, 2017

Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Oct 12 – 28, 2017 Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Aug 3 – 19, 2017

Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Aug 3 – 19, 2017 Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Jun 15 – 24, 2017

Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Jun 15 – 24, 2017