Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Jun 24 – Jul 30, 2022

Playwright: Merlynn Tong

Director: Tessa Leong

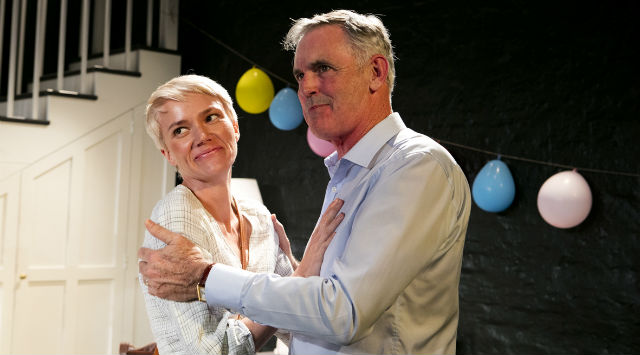

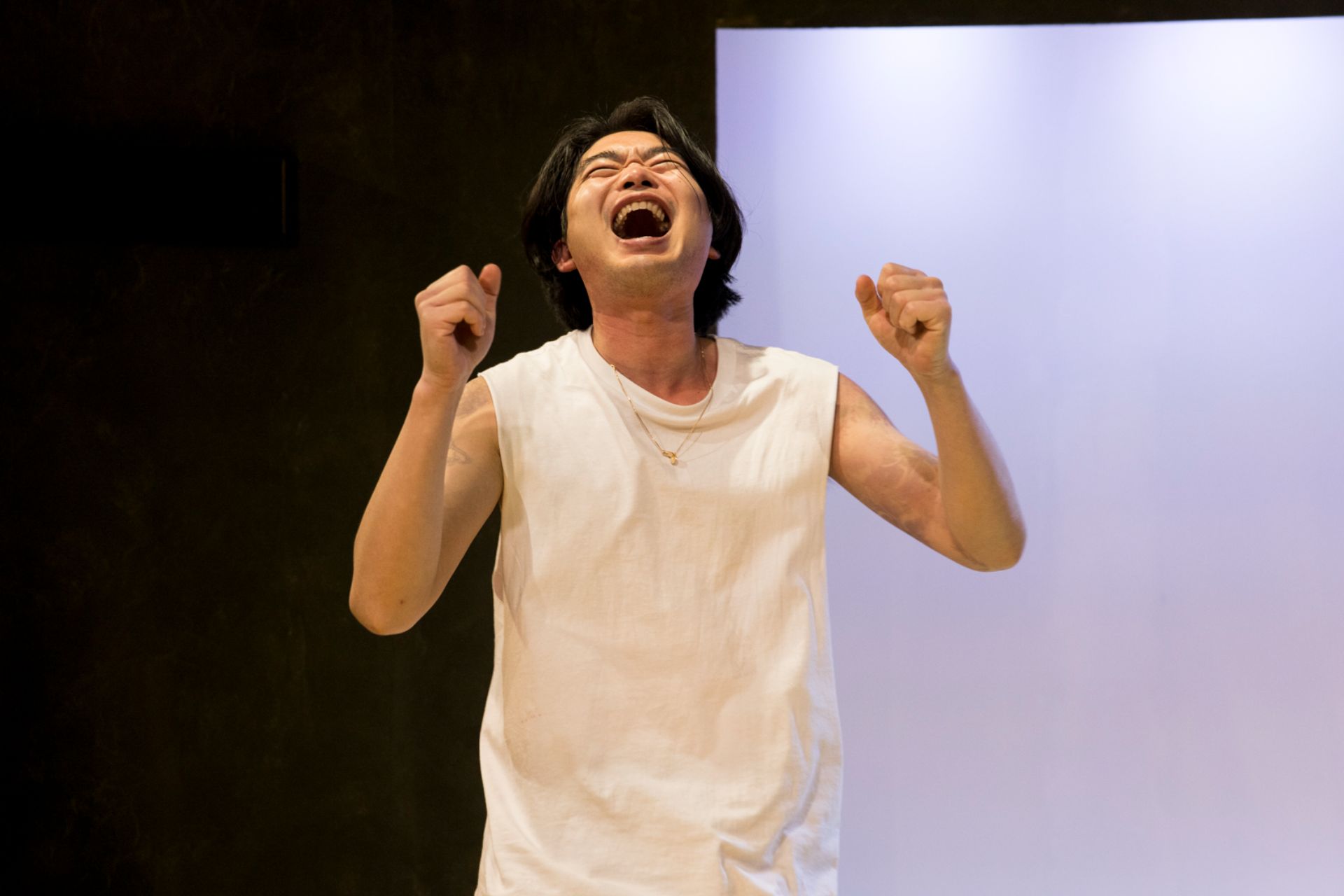

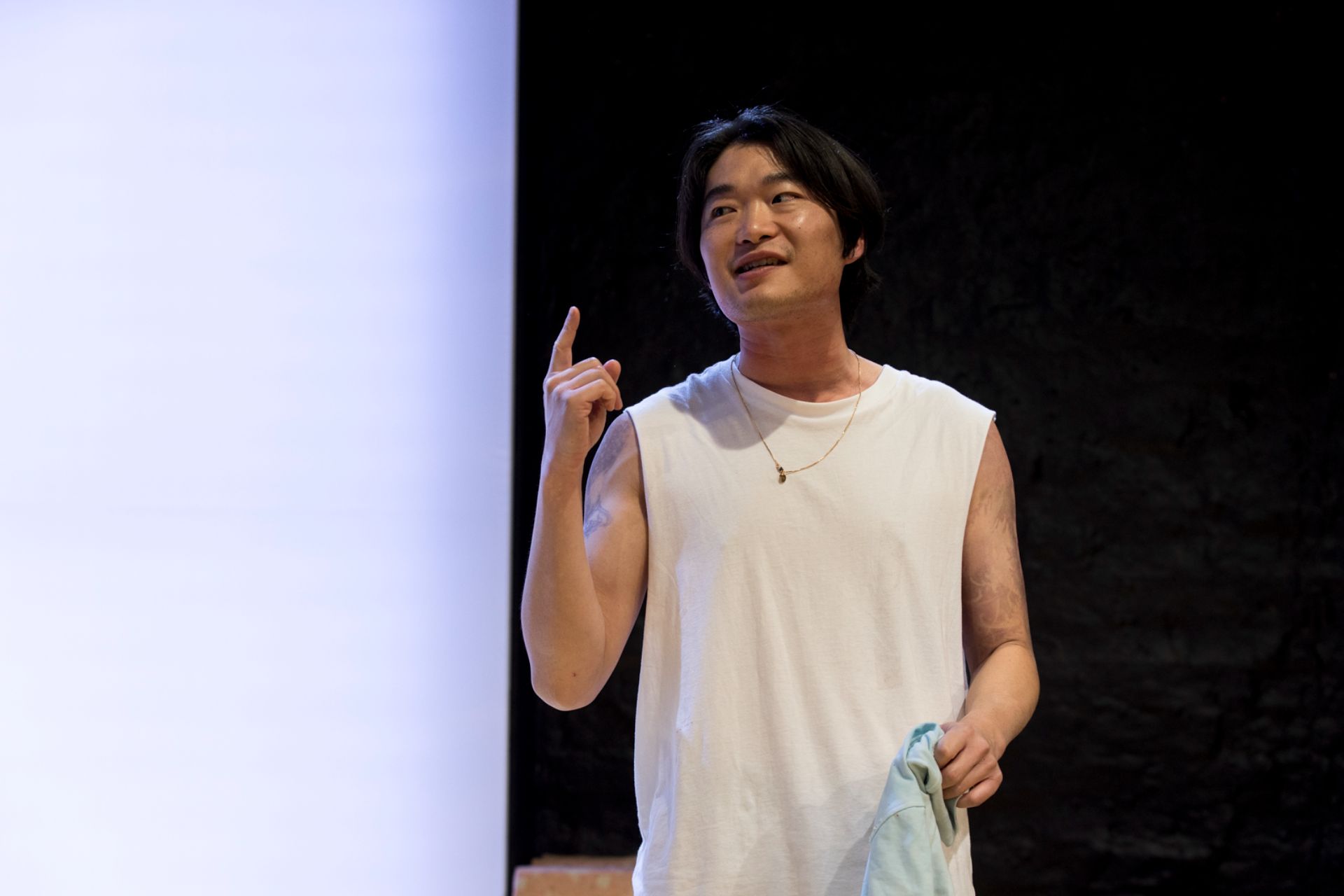

Cast: Merlynn Tong, Charles Wu

Images by Brett Boardman

Theatre review ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Girl, 14 and Boy, 21 find themselves orphaned upon their mother’s suicide. Having only each other to depend on, the two quickly grow closer, in a social vacuum that sees the wayward older sibling exercise increasingly undue influence on the innocent teen. Merlynn Tong’s Golden Blood takes place in late 90s Singapore, where unlawful gang activities, of which Boy was a committed member, were still making the news. In fear of bringing embarrassment to their family legacy, the young pair hatch creative but corruptive plans to make their fortune, on a land that places veneration on all things gold.

Tong’s writing is exciting and exceptionally colourful. Much of the dialogue in Golden Blood is in Singlish, but the “creole” is carefully crafted, in order that standard English speakers are not left behind. The humour in Tong’s work is thoroughly scintillating, with a broad appeal that transcends cultures. Furthermore the incorporation of Australia as a symbol for Girl’s escapism and ambitions, helps position the play at a point that gives psychological access to viewers here. As the stakes escalate in its narrative, Golden Blood turns melodramatic in a way that some might find alienating, but its concluding moments are unquestionably moving.

Directed by Tessa Leong, the show although never sanctimonious, is an intense and urgent exploration of modern youth. Replete with energy and an unmistakeable air of anxiety, we are compelled from the very start to invest in this unusual coming-of-age tale, of good intentions gone bad. There are slight incongruities with the inclusion of smartphones and certain clothing items, that can cause momentary confusion regarding the era being discussed, but they are ultimately a negligible oversight.

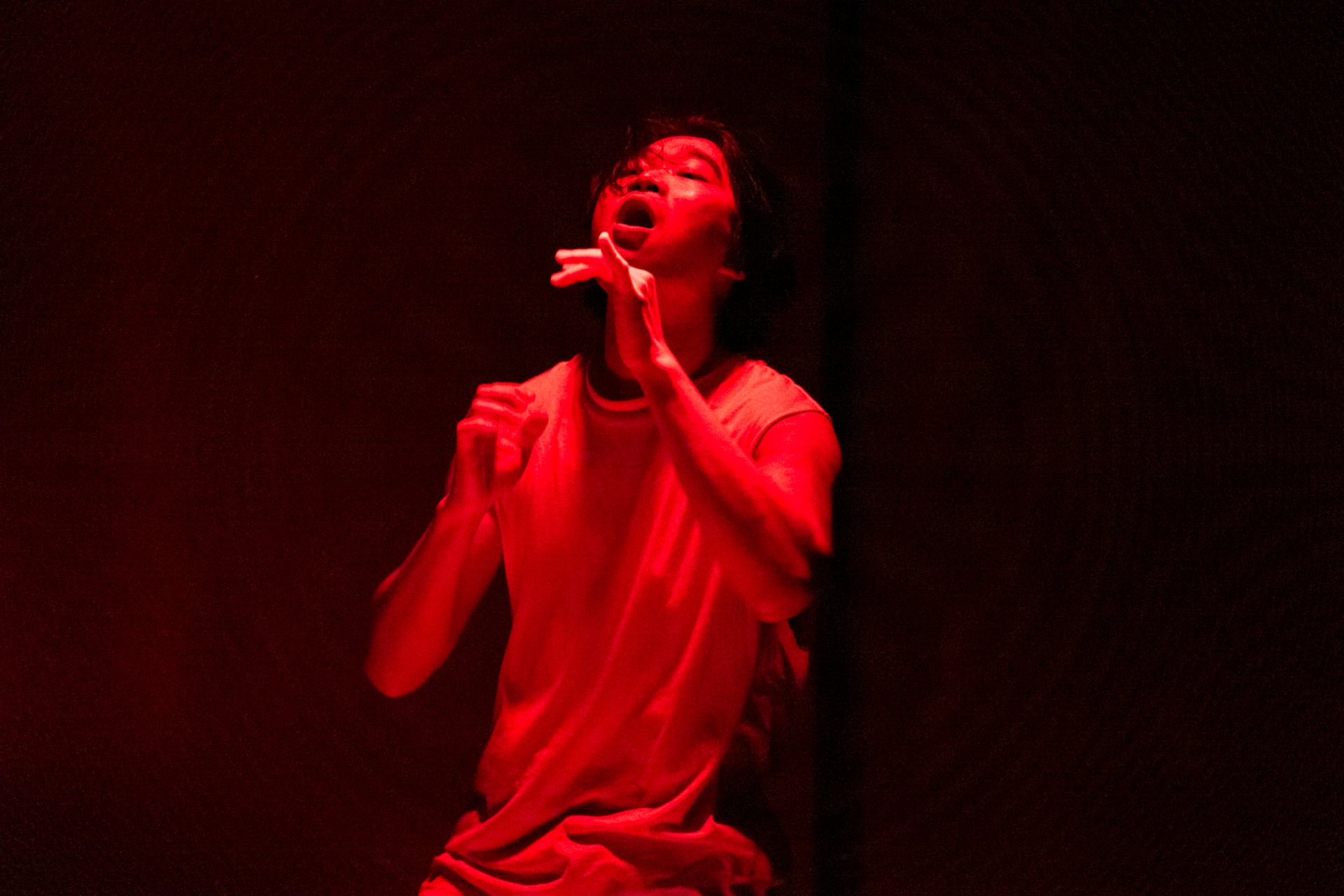

Set and costumes by Michael Hankin are efficiently rendered, and appropriately simple. In tandem with Fausto Brusamolino’s exuberant lights, visual aspects of the production are dynamic, and effective at keeping the audience in a state of consistent tension and tautness. Sound and music by Rainbow Chan are similarly spirited, with cross-cultural influences that convey a valuable complexity, in relation to time and place for this story.

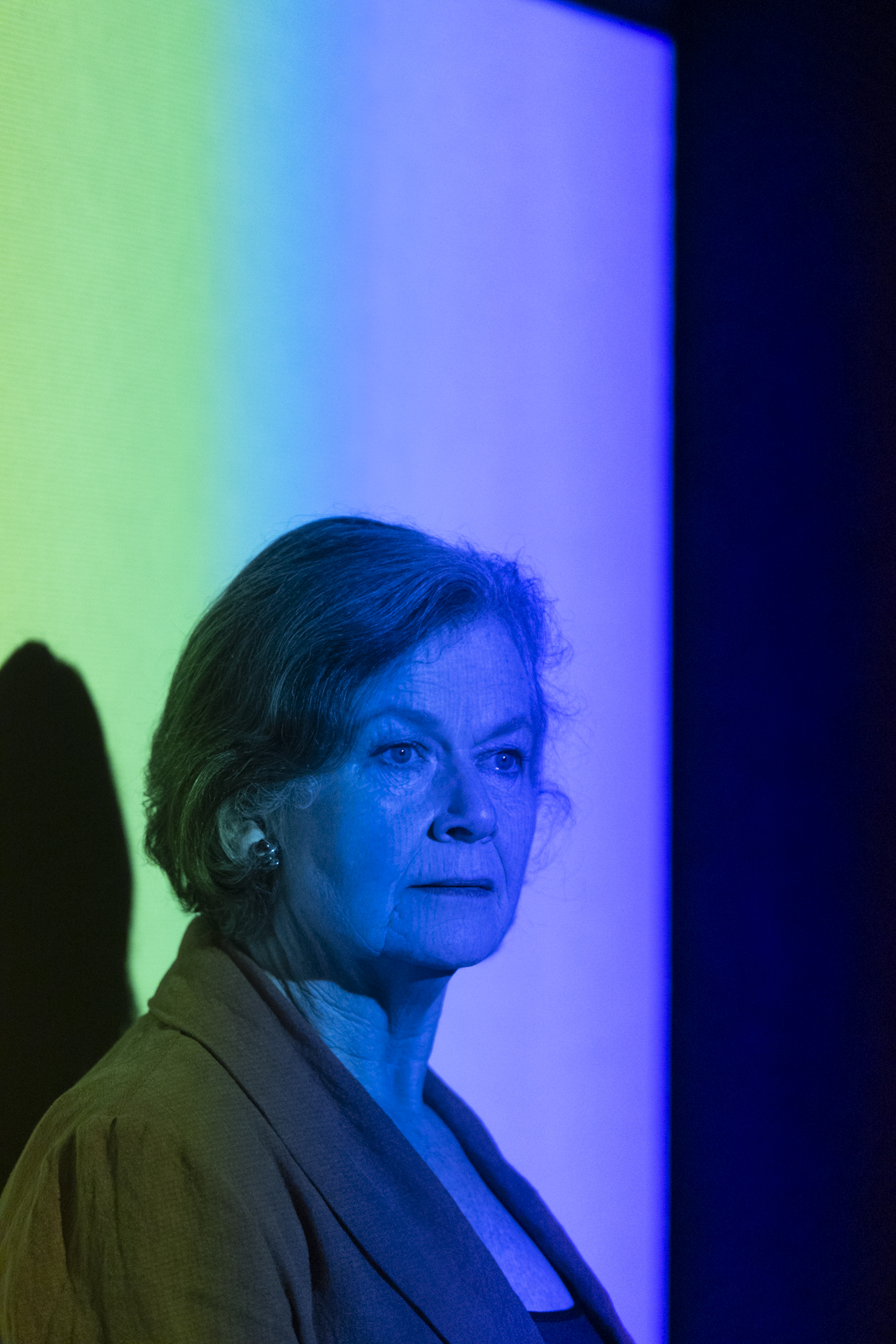

Tong herself takes on the role of Girl, profoundly moving as the misguided ingénue, but also disarmingly hilarious with her exquisite comic timing. Boy is played by Charles Wu, fantastic with the animated physicality and incredible voice he brings to the part. Their chemistry as a team is unbelievably flawless. Both actors bring a marvellous sense of depth to the characters they inhabit, allowing Golden Blood to venture into outlandish and wondrous spaces, without compromising even a fragment on authenticity.

When the definition of success is narrowed down to mean little more than material wealth, the result is an existence that can only ever be empty or exasperating. Girl and Boy were never taught right ways to be, not by their families, and not by the wider communities of which they belong. All they perceive are superficial markers of happiness, designed mostly to obfuscate and not reveal the truth. In Golden Blood we see, that the truth is persistent, even when we try hard to avoid it, and to honour it, is perhaps the only meaningful way to be.

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Jun 16 – Jul 3, 2021

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Jun 16 – Jul 3, 2021

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Apr 30 – Jun 5, 2021

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Apr 30 – Jun 5, 2021

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Apr 13 – 24, 2021

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Apr 13 – 24, 2021

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Mar 16 – 27, 2021

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Mar 16 – 27, 2021