Venue: KXT on Broadway (Ultimo NSW), Oct 31 – Nov 15, 2025

Playwrights: Zev Aviv, Lu Bradshaw, Byron Davis

Director: Lu Bradshaw

Cast: Zev Aviv, Byron Davis

Images by Valerie Joy

Theatre review

Chris and John meet at work, and an inexplicable attraction develops—something not quite romantic, yet undeniably charged with desire. When they finally give in to that magnetic pull, Chris moves on as though nothing has occurred, but John is irrevocably altered. His encounter with Chris has changed something fundamental in his mind, body, and perhaps even his soul. Monstrous keeps its meaning deliberately elusive, as if subscribing to the modern dictum, “if you know, you know.”

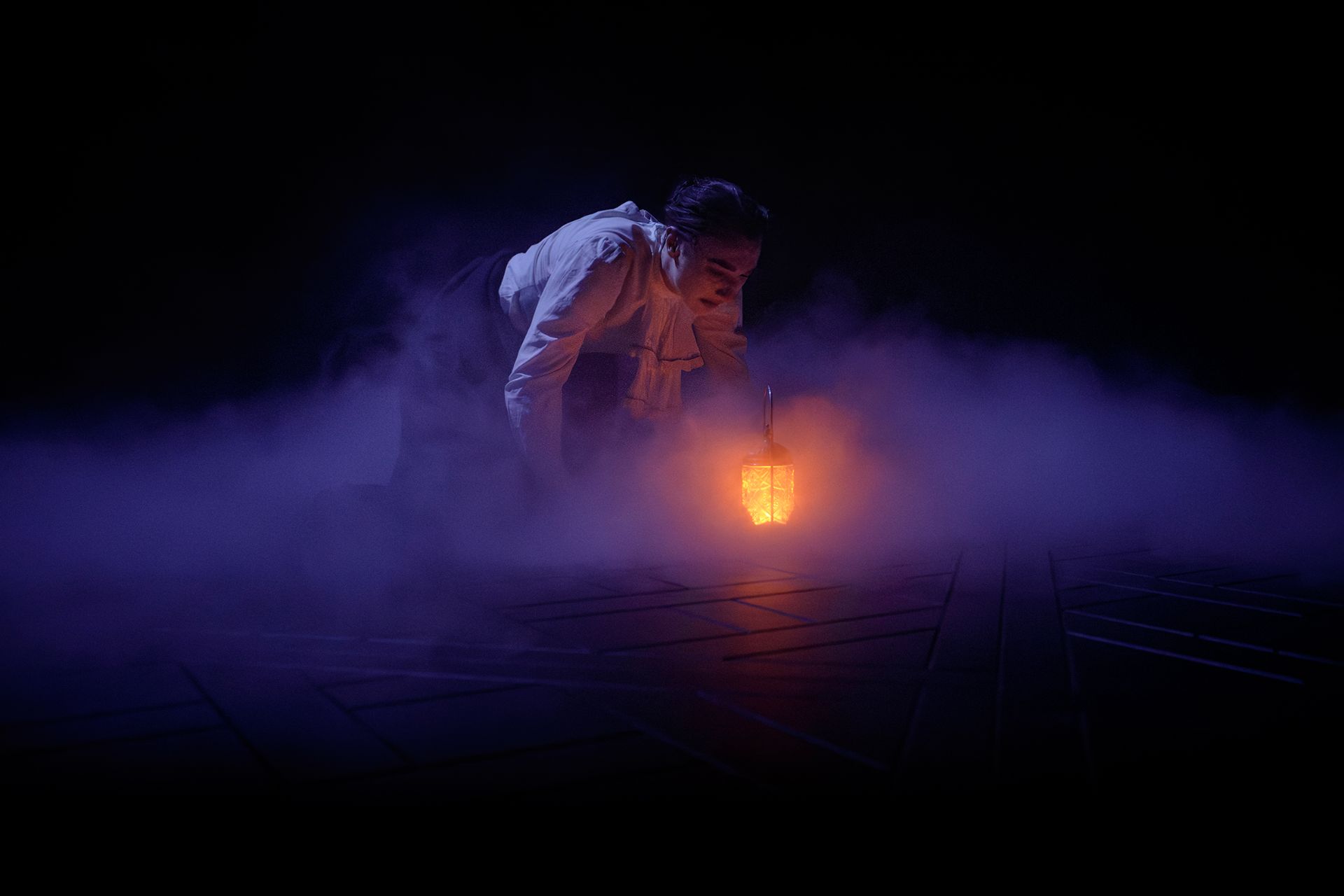

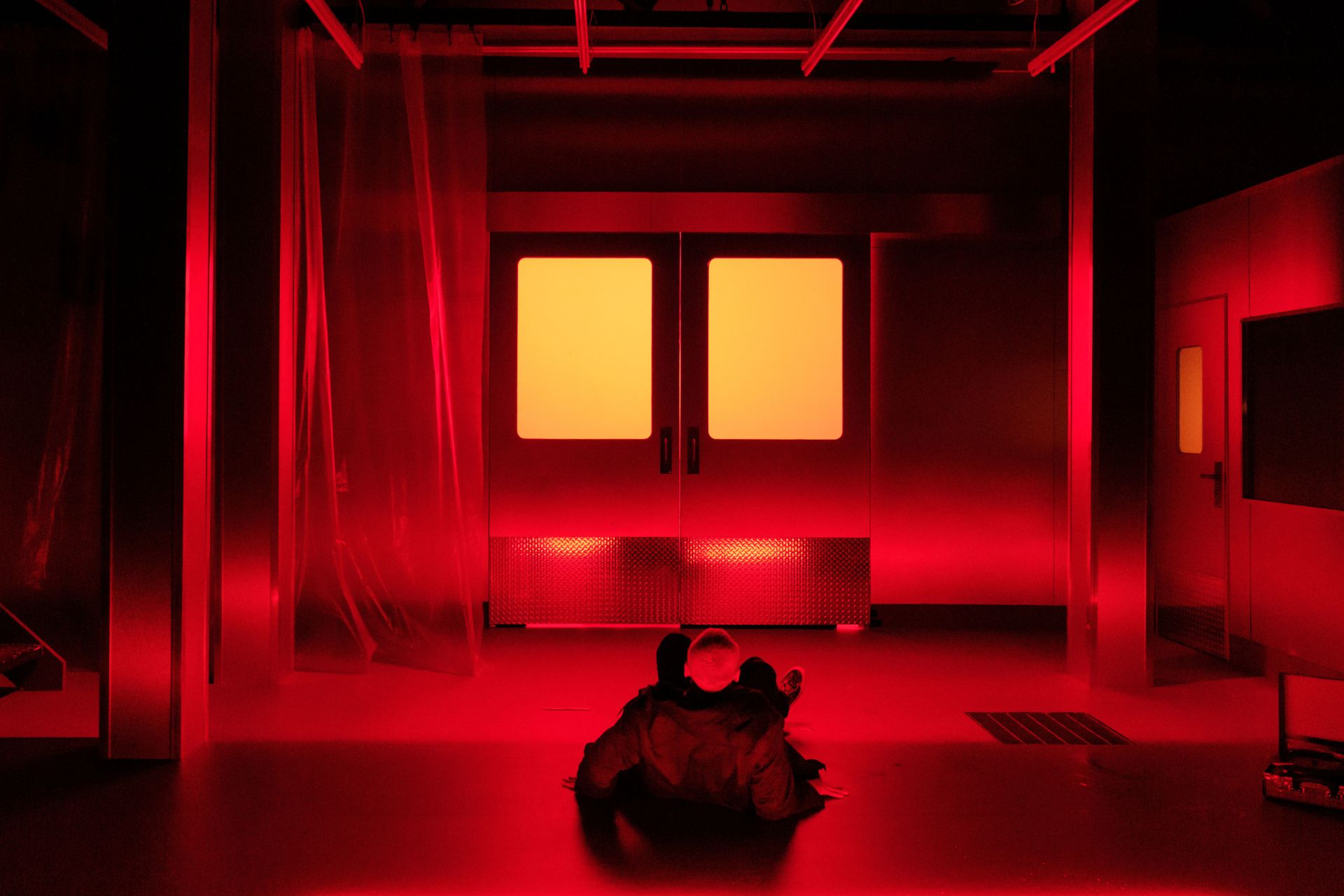

Lu Bradshaw’s direction fuses horror and the supernatural to conjure a meditation on embodiment—how the body can betray, transform, or transcend itself—exploring corporeal experience in all its contradictions: metaphysical yet visceral, intimate yet alien, and ultimately revealing the uneasy truth that our bodies are never as stable as we believe them to be.

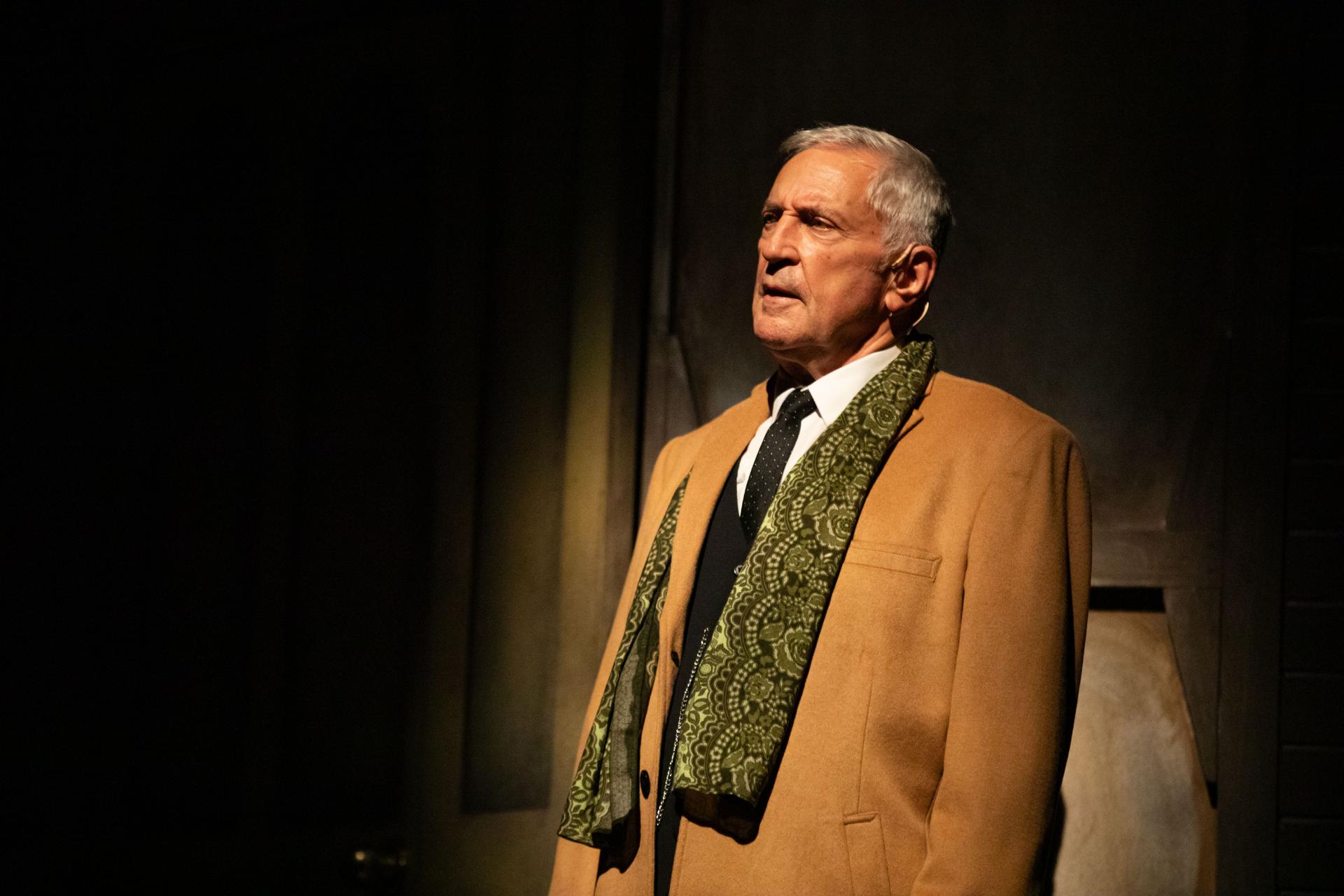

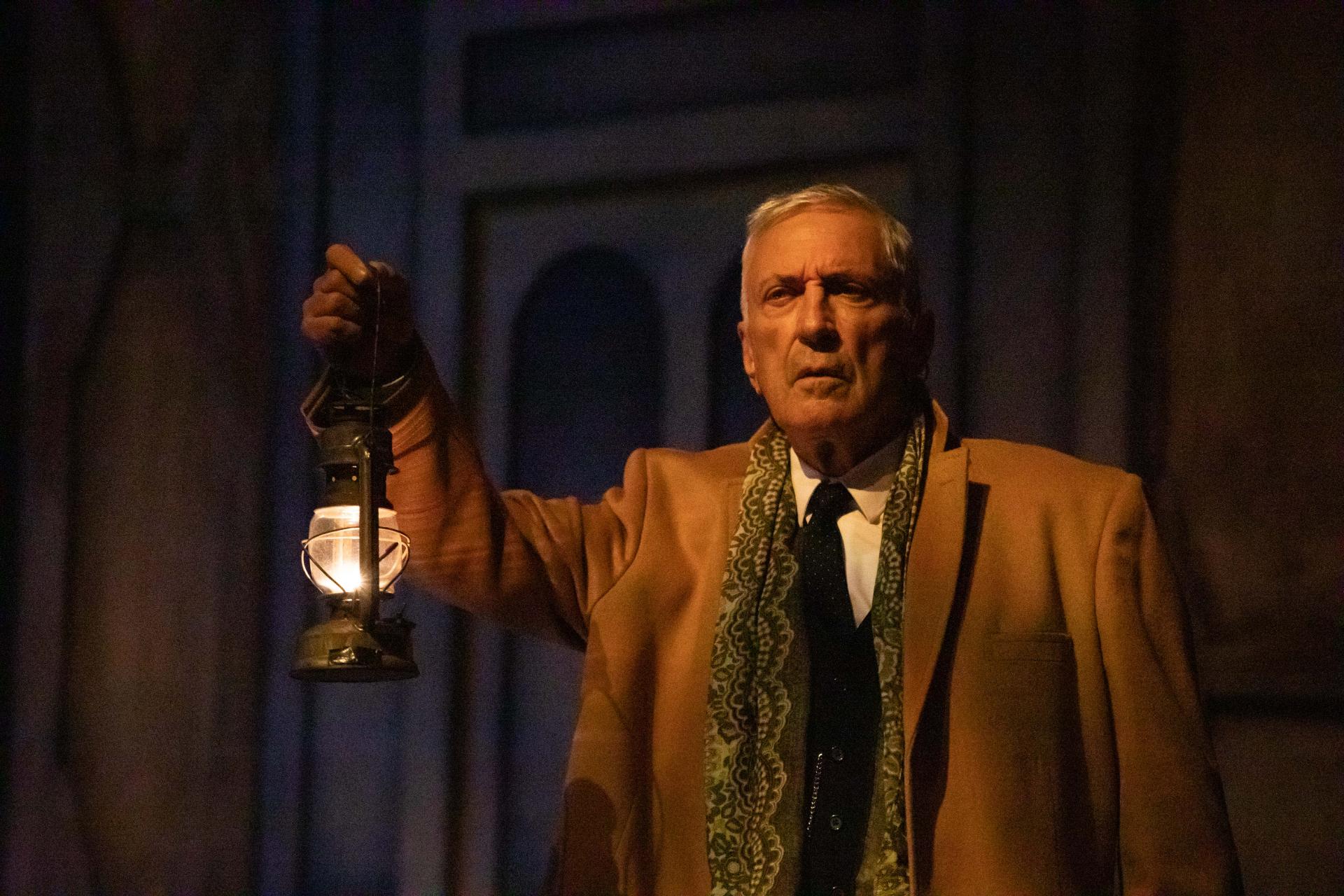

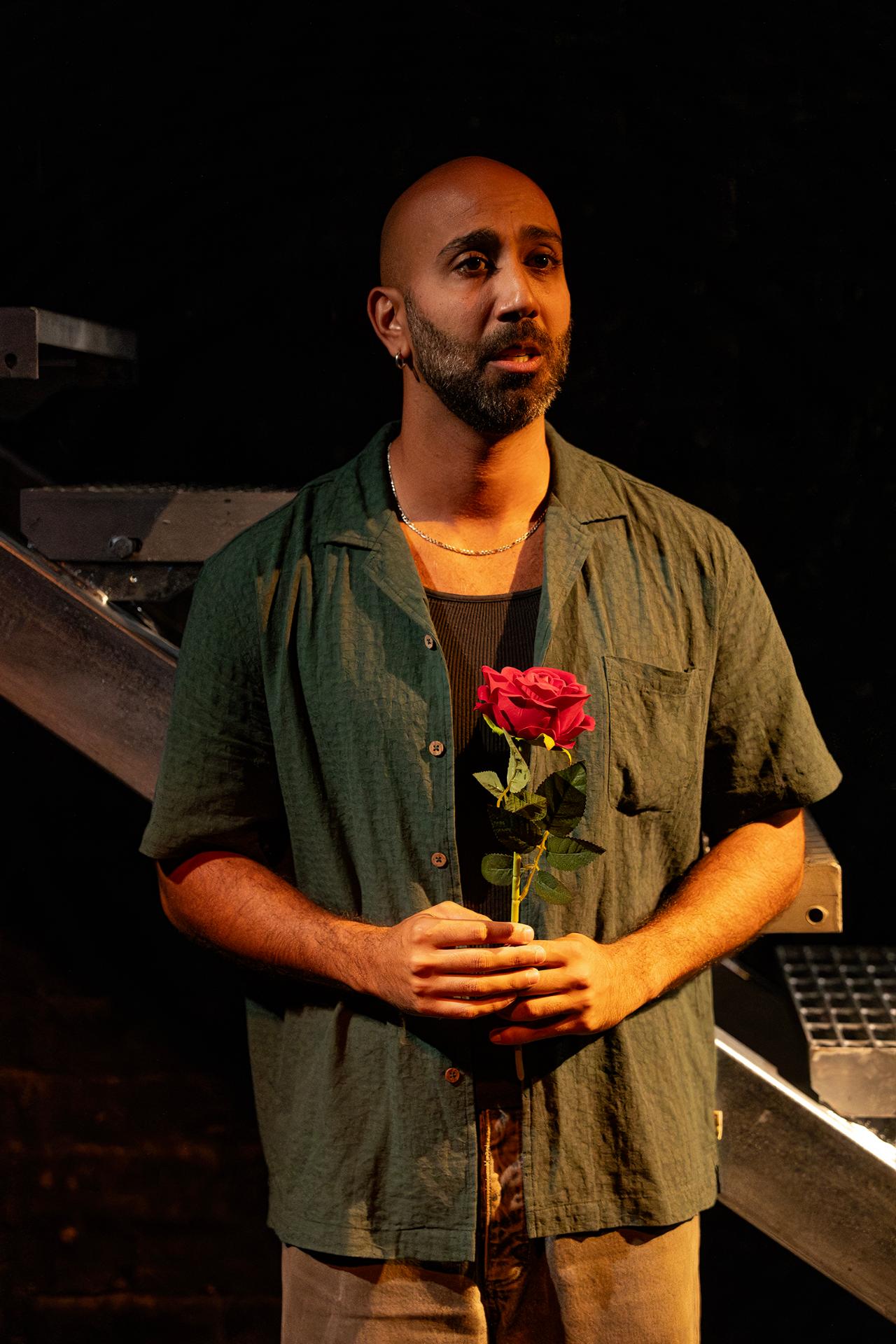

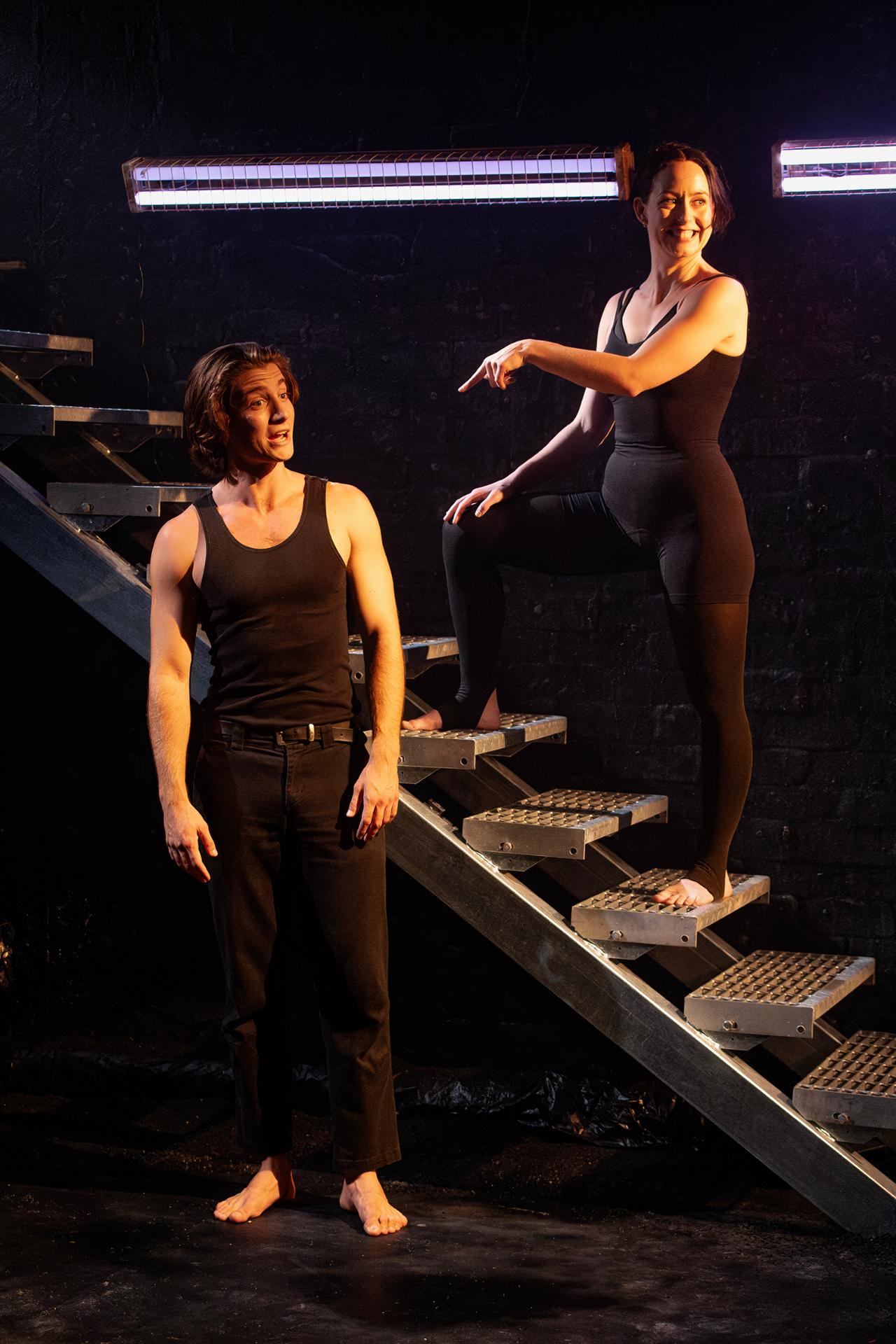

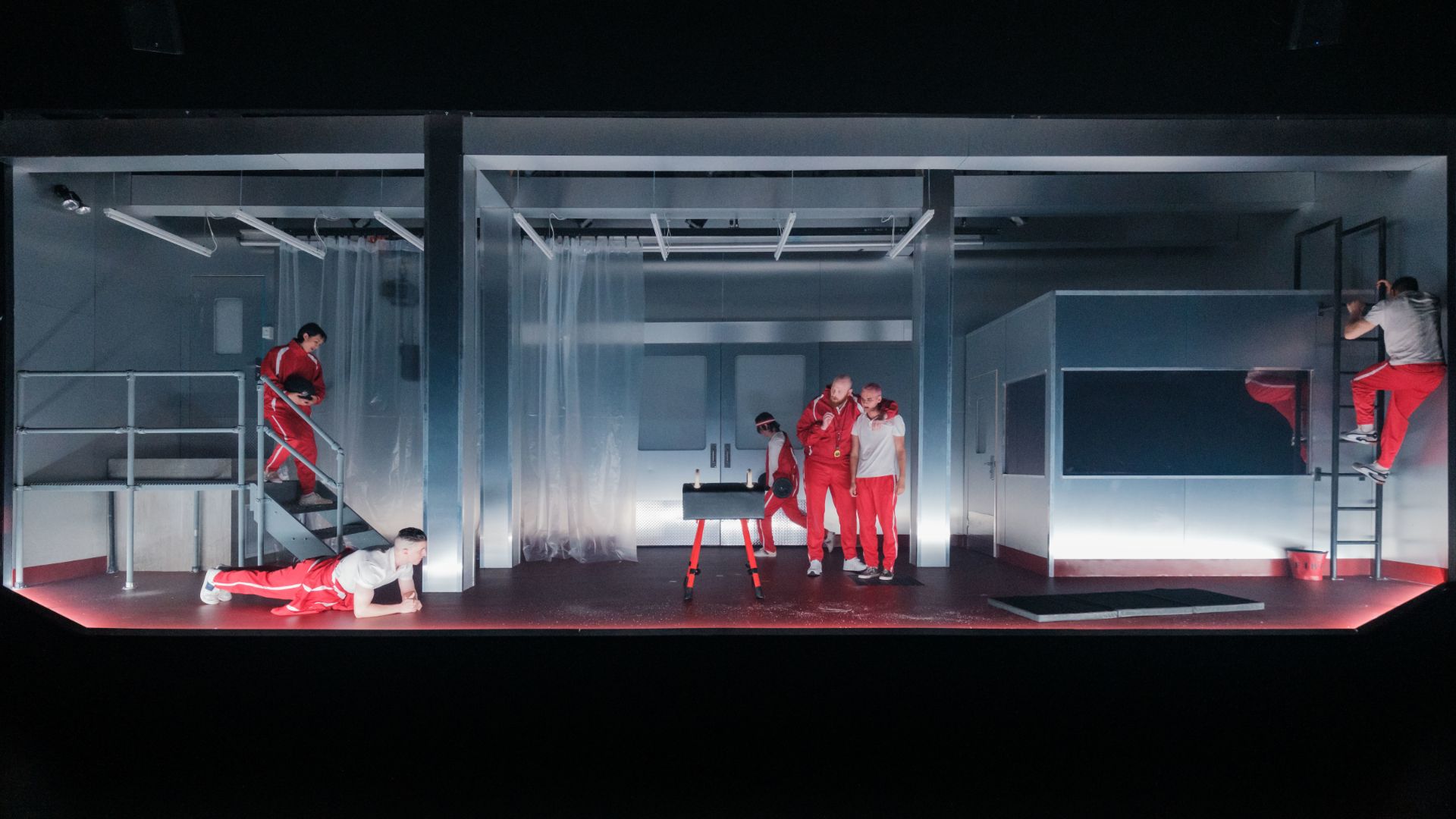

Zev Aviv plays Chris with a compelling ambiguity of intent, yet an identity that is unmistakably trans. Their very presence signals that Monstrous’ meditations on flesh and blood emerge from a distinctly trans gaze, even if the work never makes that perspective explicit. Byron Davis, as John, is bright and mercurial, his performance brimming with restless energy that draws us in completely—by turns beguiling and bewildering, but always alive.

Corey Lange’s set design is understated yet effective, grounding the production in recognisable, everyday spaces. Lighting by Theodore Carroll and Anwyn Brook-Evans is boldly executed, heightening the story’s sense of the fantastical and encouraging us to see the body anew. Ellie Wilson’s sound design adds both intensity and texture, its esoteric undercurrents propelling us toward a heightened awareness of our physical selves, creating an aural landscape that seems to pull our bodies into the mystery it seeks to unveil.

John is one thing one moment, and something entirely different the next. What emerges takes him completely by surprise, leaving him powerless to resist. His own body becomes unfamiliar terrain—something alien, unpredictable, and alive with hidden will. There are many moments in life when our bodies can feel foreign to us: strange, unrecognisable, beyond our control. The body remains an endless mystery, even as we insist on treating it as something fixed and knowable. That tension between discovery and fear is where the terror lies—in realising that what feels monstrous may only ever be natural, when its strangeness refuses to conform and the body asserts itself in ways our simple minds cannot quite comprehend.

www.kingsxtheatre.com | www.instagram.com/red_zebra_productions

Venue: Kings Cross Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Jan 29 – Feb 13, 2021

Venue: Kings Cross Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Jan 29 – Feb 13, 2021

Venue: Carriageworks (Eveleigh NSW), Jan 13 – 17, 2021

Venue: Carriageworks (Eveleigh NSW), Jan 13 – 17, 2021

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Feb 11 – 15, 2020

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Feb 11 – 15, 2020