Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Nov 5 – Dec 11, 2021

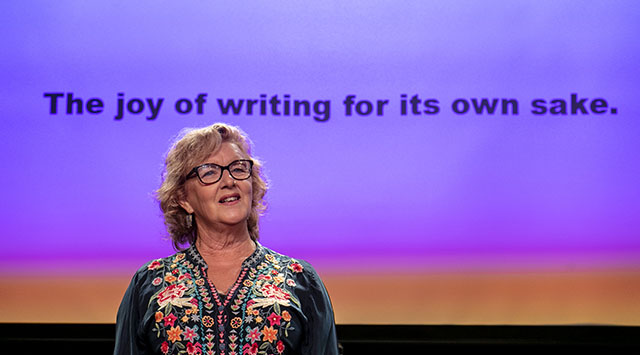

Playwright: Kendall Feaver

Director: Tessa Leong

Cast: Tony Cogin, Emily Havea, Mark Paguio, Jane Phegan, Fiona Press, Julia Robertson

Images by Brett Boardman

Theatre review

When Paige Hutson is raped in her own room, barely a week into life as a fresher at one of Australia’s oldest residential colleges, it becomes apparent that sexual assault on campus is exceedingly commonplace, and that entrenched mechanisms purporting to deal with these egregious trespasses serve only to protect the system, and not the victims. Kendall Feaver’s “Wherever She Wanders” is a strangely polite look at how a young feminist Nikki Faletau navigates her activism, within the conservative walls of a structure that is perhaps the most patriarchal of all our institutions.

The play’s ideas are modern, but not radical by any stretch of the imagination. It may even seem to occasionally be sitting on the fence, in its attempts to prevent characters from turning caricature. While “Wherever She Wanders” may not convey the incendiary passion often associated with political movements of our time, it certainly paints a cogent picture of the dynamics at play. Feaver takes a lot of care to map out many issues unearthed by that one horrific incident, but it is debatable if the granularity at which it examines them is necessary, at a time when matters of this nature are already stringently scrutinised in so much of our discourse.

Staging of the piece is humorous and jaunty. Directed by Tessa Leong, the show never fails to feel spirited, with an excellent attention to energy levels, aided by the commendable work contributed by designers, most notably Govin Ruben on lights, and James Brown on sound and music. “Wherever She Wanders” is engaging at every juncture, if slightly deficient in terms of the intellectual rigour, that a narrative of this nature should be able to provide.

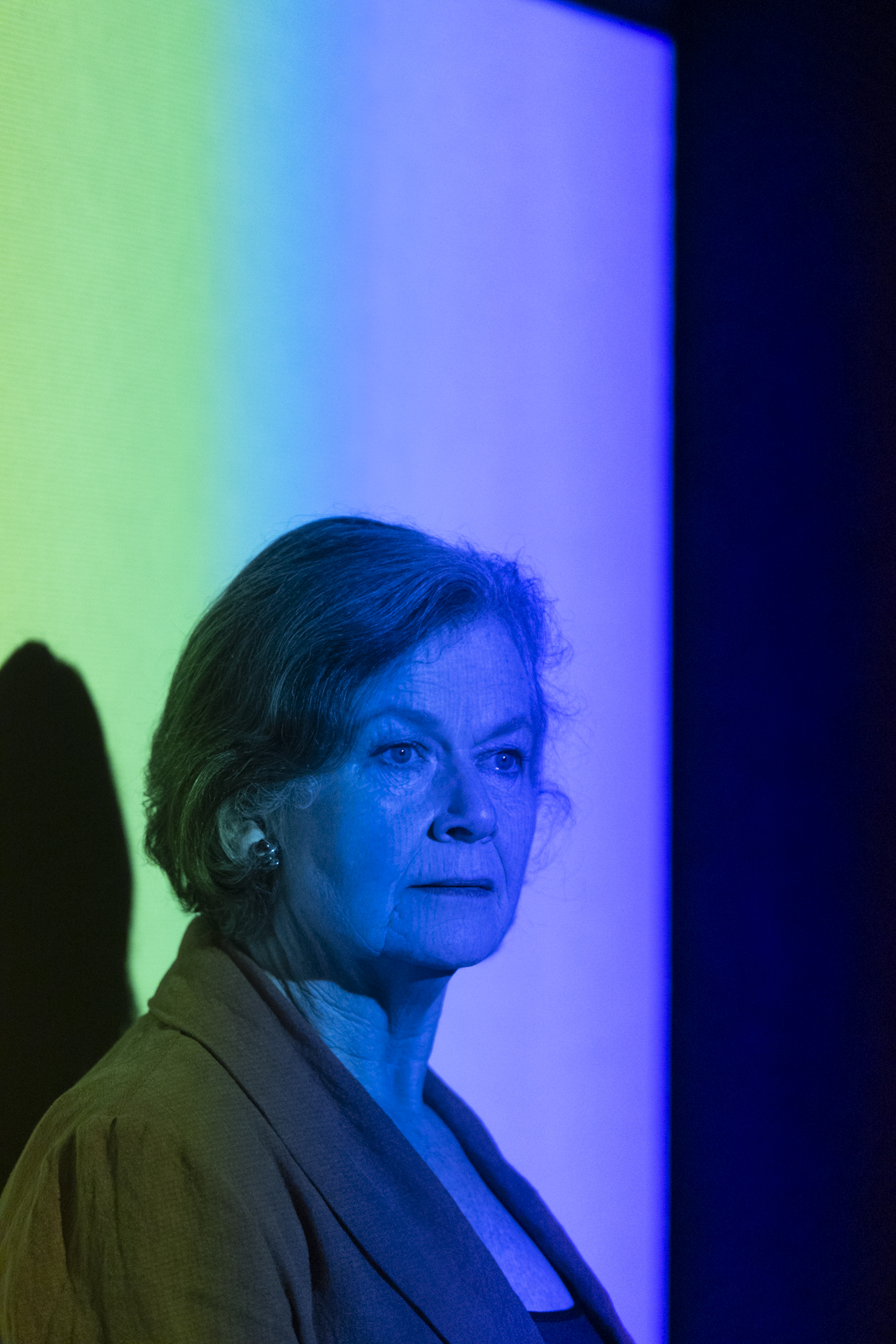

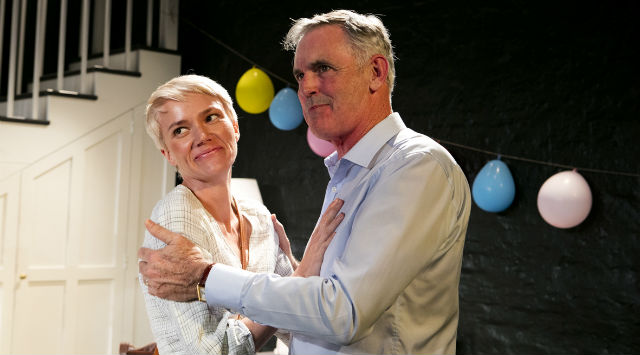

Presented by an amiable cast, with the vivacious Emily Havea as lead, bringing a valuable intensity to the earnest advocate Nikki. It is her vitality that gives the production, and the topics of discussion, a sense of authenticity and gravity. Her adversary Jo Mulligan is College Master, and feminist from a bygone era. Played by Fiona Press, who demonstrates great empathy for the role, inviting us to think about the way gatekeepers operate in our daily lives. Actor Julia Robertson does marvellously to deliver for Paige, an abundance of complexity and nuance, so that we may locate both agency and integrity for a young woman in danger of being defined solely by an instance of violation.

Whether one believes that the systems have become broken through the ravages of time, or that the systems were always designed to fail so many of us, one should already have come to the conclusion that it seems only drastic measures, can address all the foundational and fundamental problems that plague our traditional institutions. We observe Nikki’s persistence as she goes about trying to change things, but there is no evidence that the complaints and conversations she participates in, ever result in significant progress. Where there is power imbalance, the subjugated always runs the risk of being patronised. As long as the powerful remain in charge, there is never any incentive for them to do anything more than to pretend to listen. Change does occasionally occur however, and persistence seems the only tool that the disadvantaged an hang on to, aside from the ever-present fantasy of torching the whole place down.

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Apr 30 – Jun 5, 2021

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Apr 30 – Jun 5, 2021

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Apr 13 – 24, 2021

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Apr 13 – 24, 2021

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Mar 16 – 27, 2021

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Mar 16 – 27, 2021

Venue: Green Park (Darlinghurst NSW), Feb 5 – Mar 6, 2021

Venue: Green Park (Darlinghurst NSW), Feb 5 – Mar 6, 2021

Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Sep 25 – Oct 31, 2020

Venue: Seymour Centre (Chippendale NSW), Sep 25 – Oct 31, 2020

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Nov 1 – Dec 14, 2019

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Nov 1 – Dec 14, 2019

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Sep 6 – Oct 12, 2019

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Sep 6 – Oct 12, 2019

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Jul 26 – Aug 31, 2019

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Kings Cross NSW), Jul 26 – Aug 31, 2019