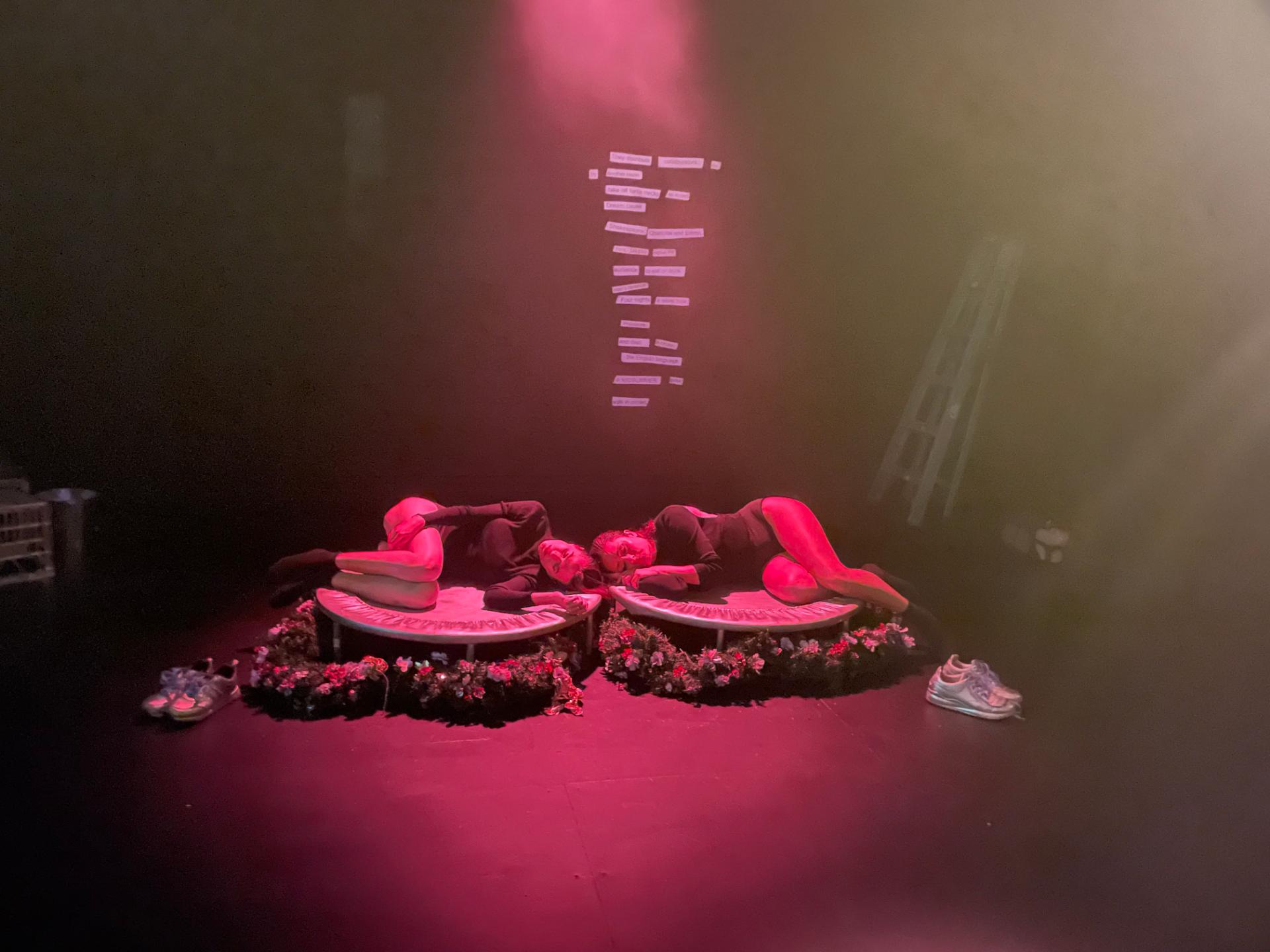

Venue: Old Fitzroy Theatre (Woolloomooloo NSW), Dec 1 – 10, 2023

Creators: Charlotte Farrell, Emma Maye Gibson

Theatre review

Feminists are not usually fans of Shakespeare’s oeuvre; his representations of women are often nauseating, if not completely despicable. Charlotte Farrell and Emma Maye Gibson seem to have a love-hate relationship with The Bard. A Midsummer Night’s Cream is a devised work that is both inspired by, and critical of Shakespeare. Early portions of the show are heavily centred around deconstructions of Shakespeare’s writing, reflecting perhaps a frustration derived from making theatre in a milieu that regards him to be foundational and epochal, even centuries later.

The show then swirls gradually away from that point of departure, and ventures somewhere more intimate, with Farrell and Gibson discussing motherhood. An intensification of atmosphere, luminated with a palpable sensuality by Cheryn Frost, almost indicates the true purpose of the exercise, as the two women engage in exchanges that explore those meanings that pertain to the young cisgender female body. Like Shakespeare being so intrinsically linked to how he conceive of the theatrical arts, pregnancy is to many women, inextricable and integral to their understanding of existence.

None of this is ever made explicit however, in a presentation that is as whimsical as it is poetic. Political but never pugnacious, A Midsummer Night’s Cream asserts itself with only the smallest affront to what it wishes to abolish, choosing instead to establish on stage, a new order that, unlike its predecessor, is characterised by inclusiveness and grace. Empowered to make change, with a humility informed by past deficiencies, Farrell and Gibson are careful not to inflict the same egregiousness it tries to replace.

This is a feminism that does not merely substitute one thing for another, preserving old structures while temporarily and superficially transforming them. What the artists deliver, looks like disruptive chaos, but that probably says more about our attachment to obsolete values, than it does the essential qualities of their work. Real change is uncomfortable, and good art is never afraid to challenge.