Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Oct 4 – Nov 9, 2025

Creator: Meow Meow

Director: Kate Champion

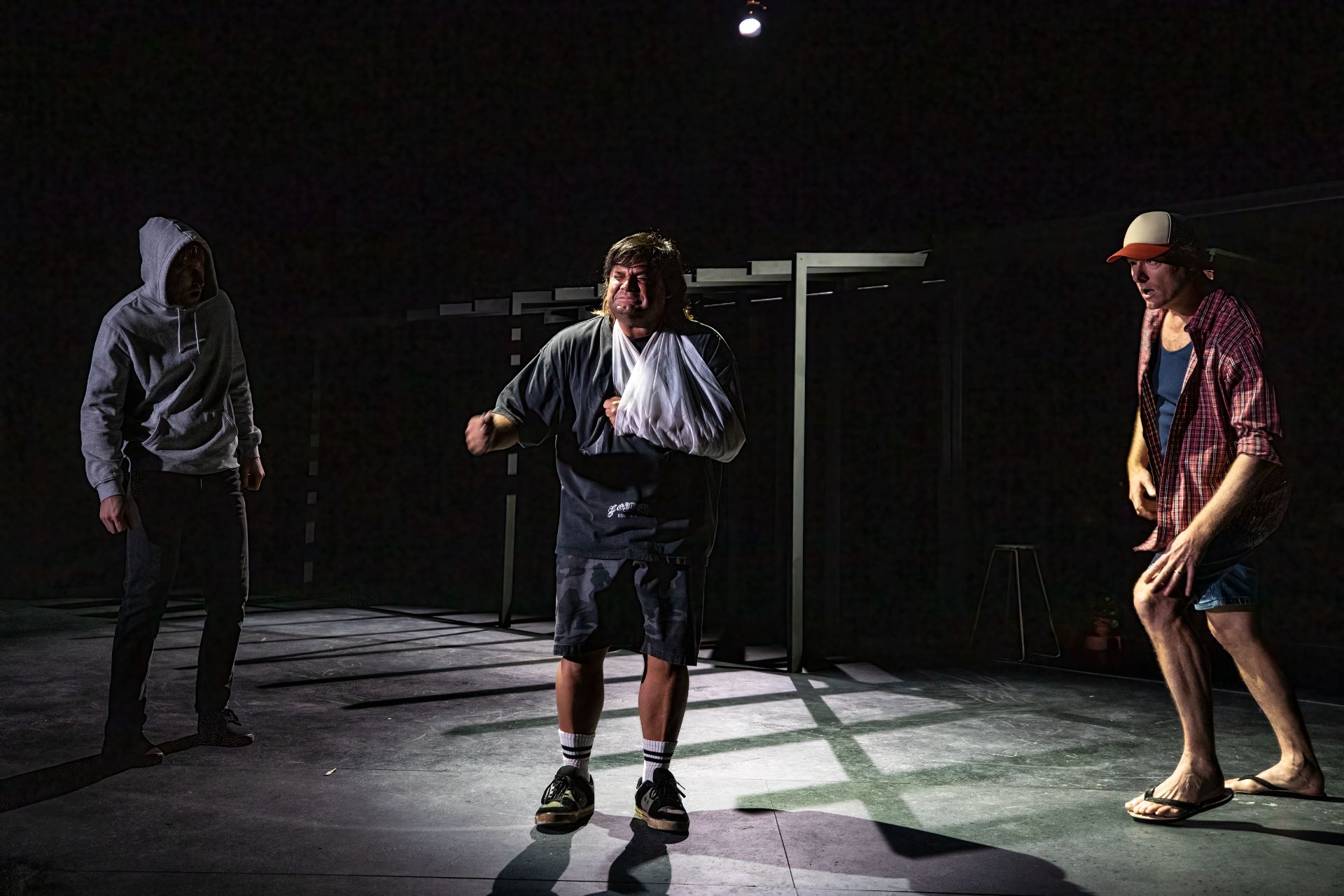

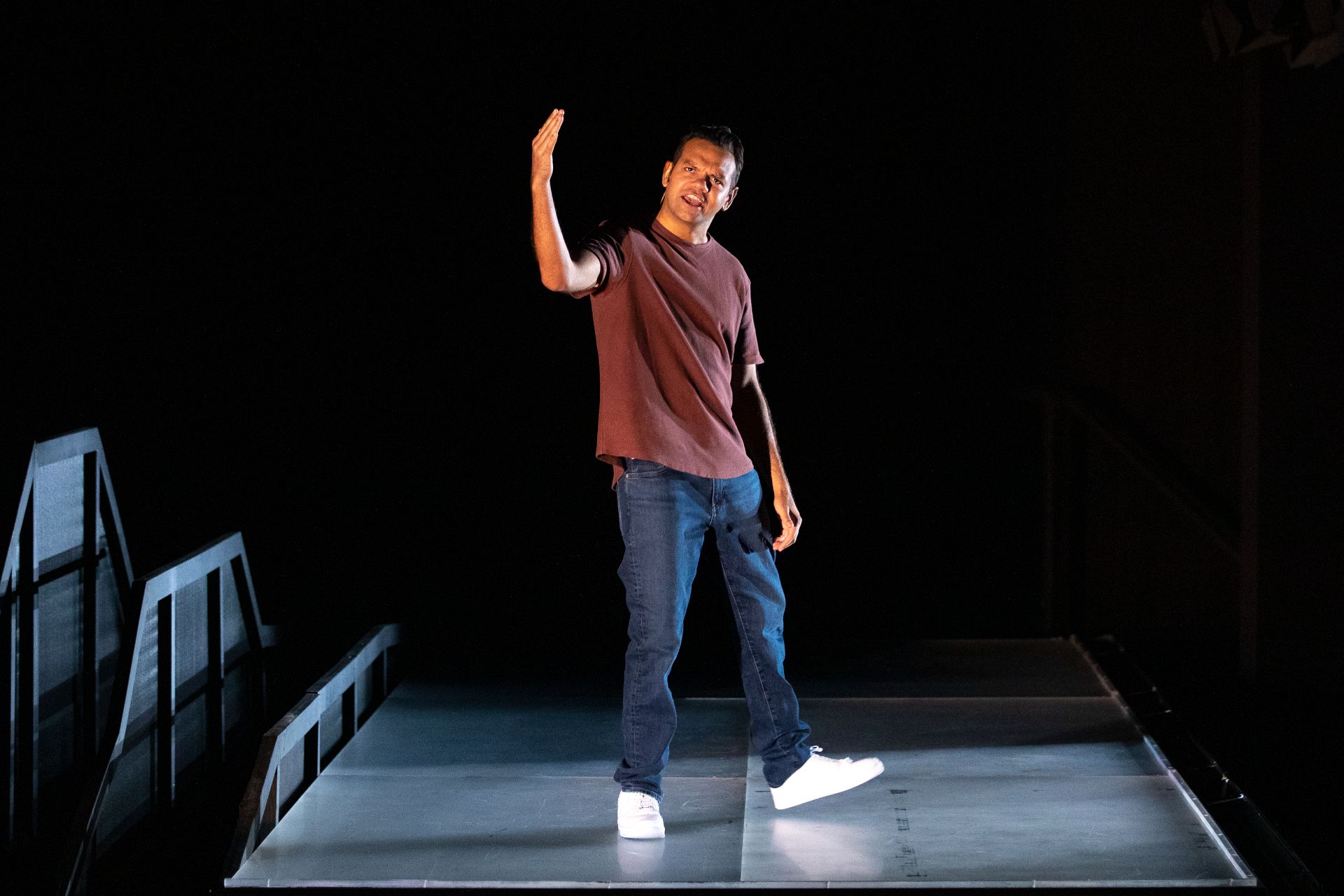

Cast: Kanen Breen, Mark Jones, Meow Meow, Dan Witton, Jethro Woodward

Images by Brett Boardman

Theatre review

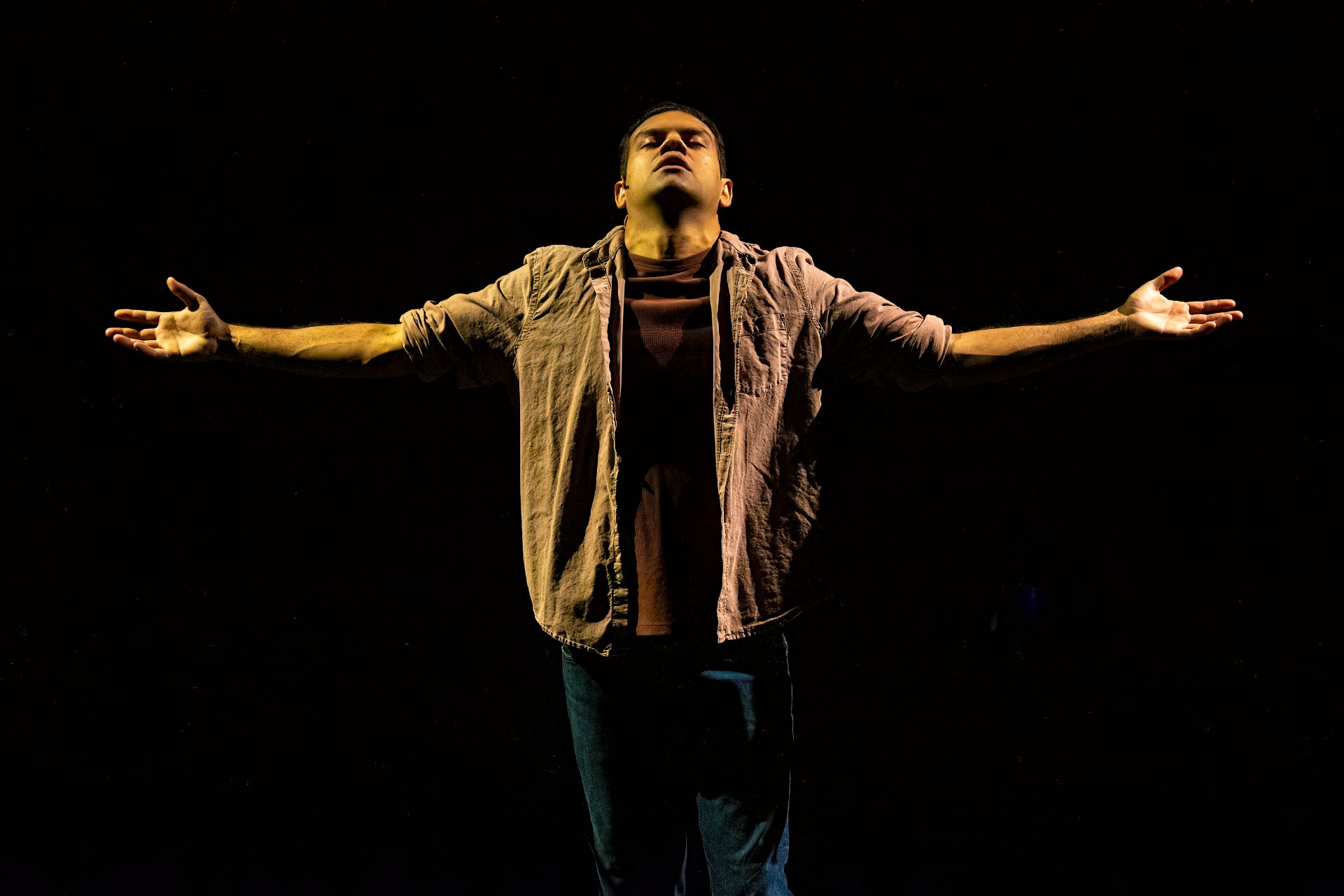

In Hans Christian Andersen’s original tale, a young girl is condemned to dance without end, her obsession consuming her entire being. Meow Meow’s The Red Shoes transforms this fable into a self-reflexive performance piece, with Meow Meow — the self-proclaimed “eternal showgirl” — embodying an autobiographical figure who cannot stop performing, trapped in the perpetual motion of her own artistry. She describes her practice as non-linear and anti-narrative, and those qualities are evident here. Yet if the work falters, it is not because of its structural resistance to story, but rather because its gestures, however extravagant, begin to feel drained of true inspiration.

Nonetheless, Meow Meow’s song writing remains unequivocally delightful, buoyed by Jethro Woodward’s musical direction, which is both sophisticated and deeply satisfying. The staging of each number, under Kate Champion’s direction, abounds with visual allure, though the production’s overall lack of emotional resonance can leave one curiously hollow. Dann Barber’s set and costume design are splendidly realised, conjuring an atmosphere of apocalypse without ever relinquishing a sense of glamour. Meanwhile, Rachel Burke’s lighting is nothing short of transcendent, transforming the space with a radiance that is as visceral as it is luminous.

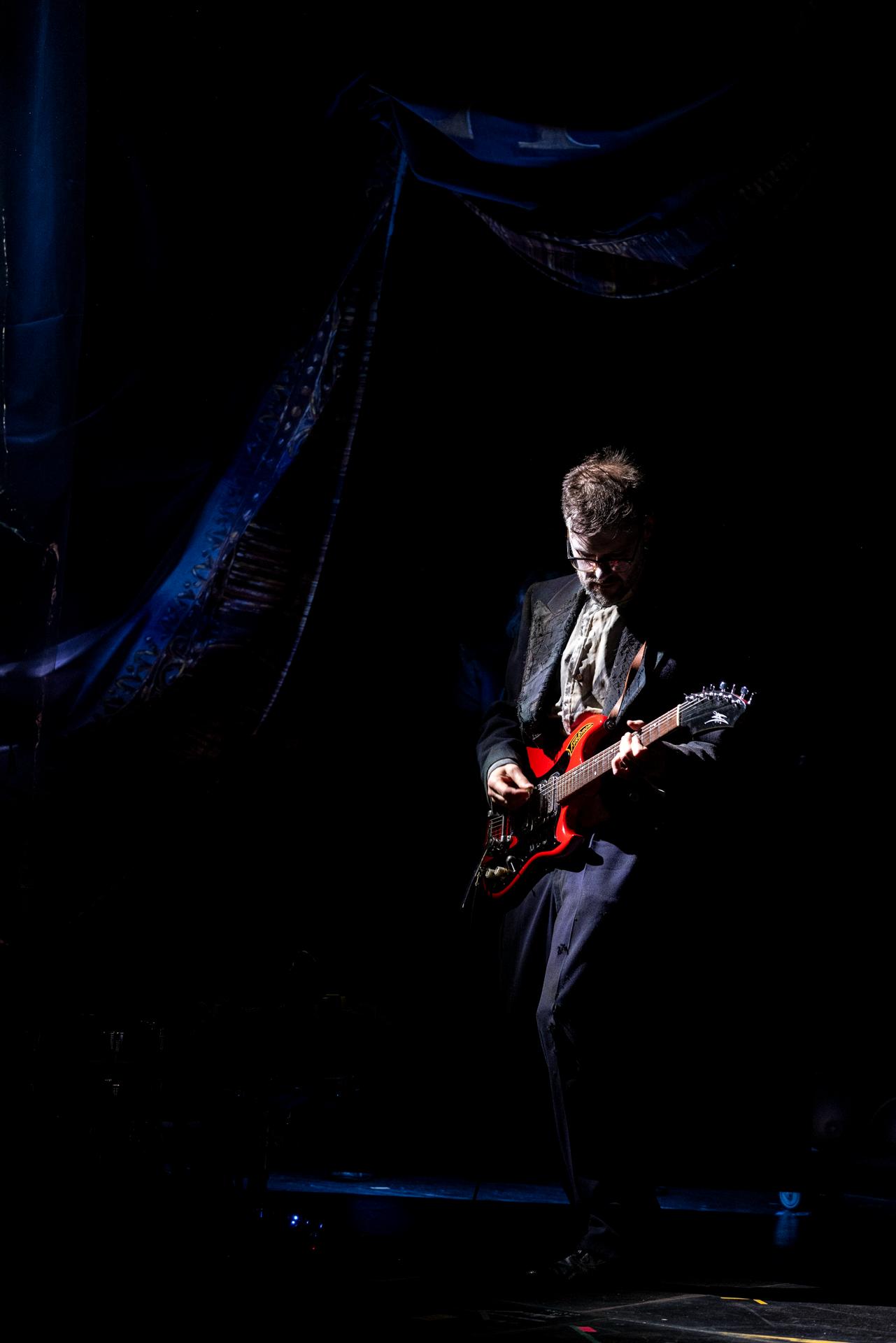

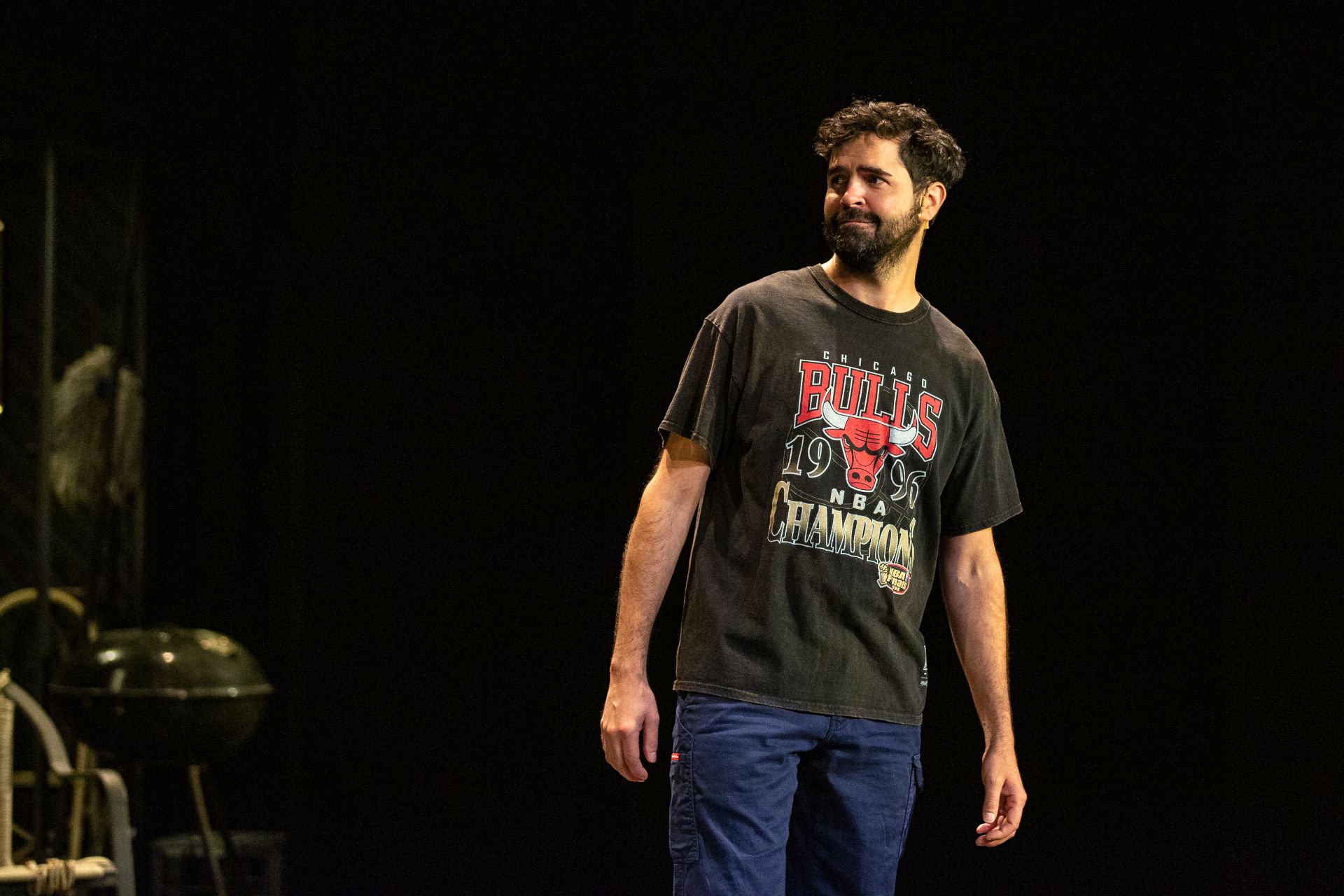

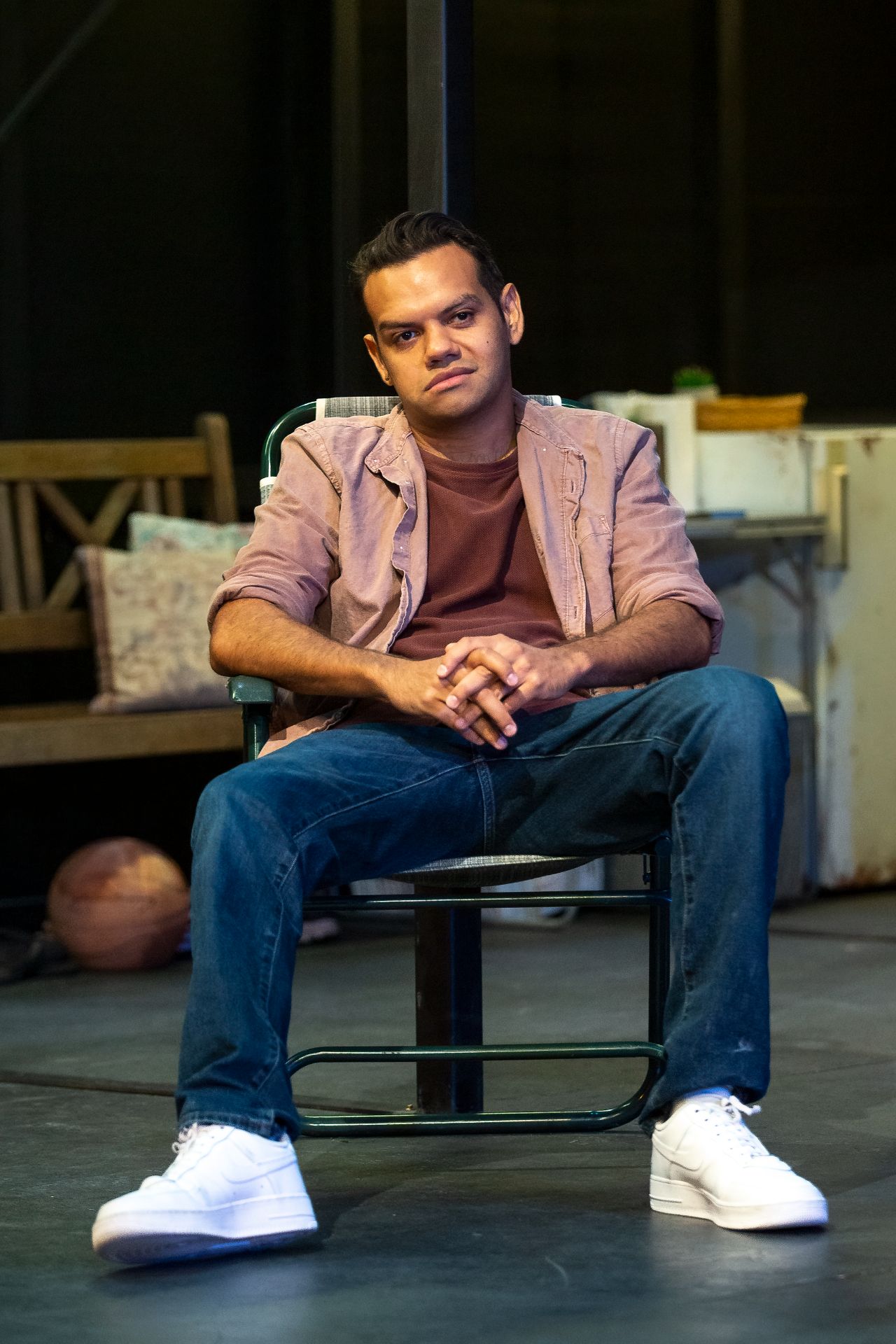

Meow Meow is, without question, a consummate performer — her voice rich and expressive, her physicality precise and magnetic. Yet beneath the impeccable technique lies a curious detachment, as though the machinery of performance turns flawlessly, but the spark within flickers faintly. In contrast, Kanen Breen radiates exuberance and conviction as her onstage companion, his presence a buoyant counterpoint that reanimates the stage. Exquisite musicians Mark Jones and Dan Witton, alongside Woodward, contribute not only live accompaniment but a heady air of bohemian decadence, infusing the production with an intoxicating sense of play.

Andersen’s 1845 tale The Red Shoes may glimmer with romance, yet beneath its sheen lies a stern puritanism — a warning against the woman who dares to follow her own desire. In Meow Meow’s hands, that cautionary fable is turned tenderly inside out: love, not vanity, becomes the pulse of her relentless motion. It is the reach for connection, not self-admiration, that keeps her dancing — as if true salvation lies in crafting communion, even in a space as fleeting and ephemeral as the theatre.

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Jul 18 – Aug 24, 2019

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Jul 18 – Aug 24, 2019