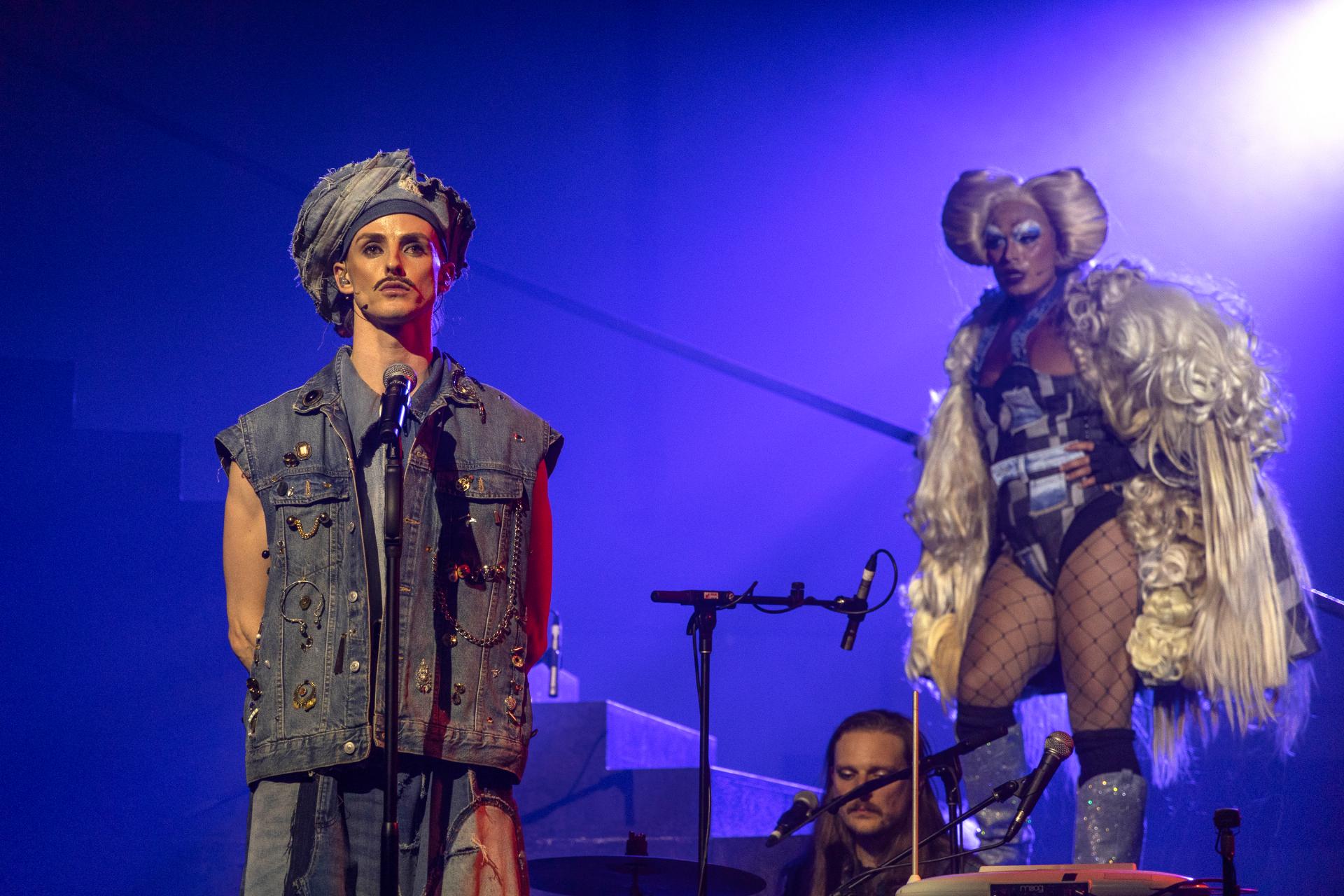

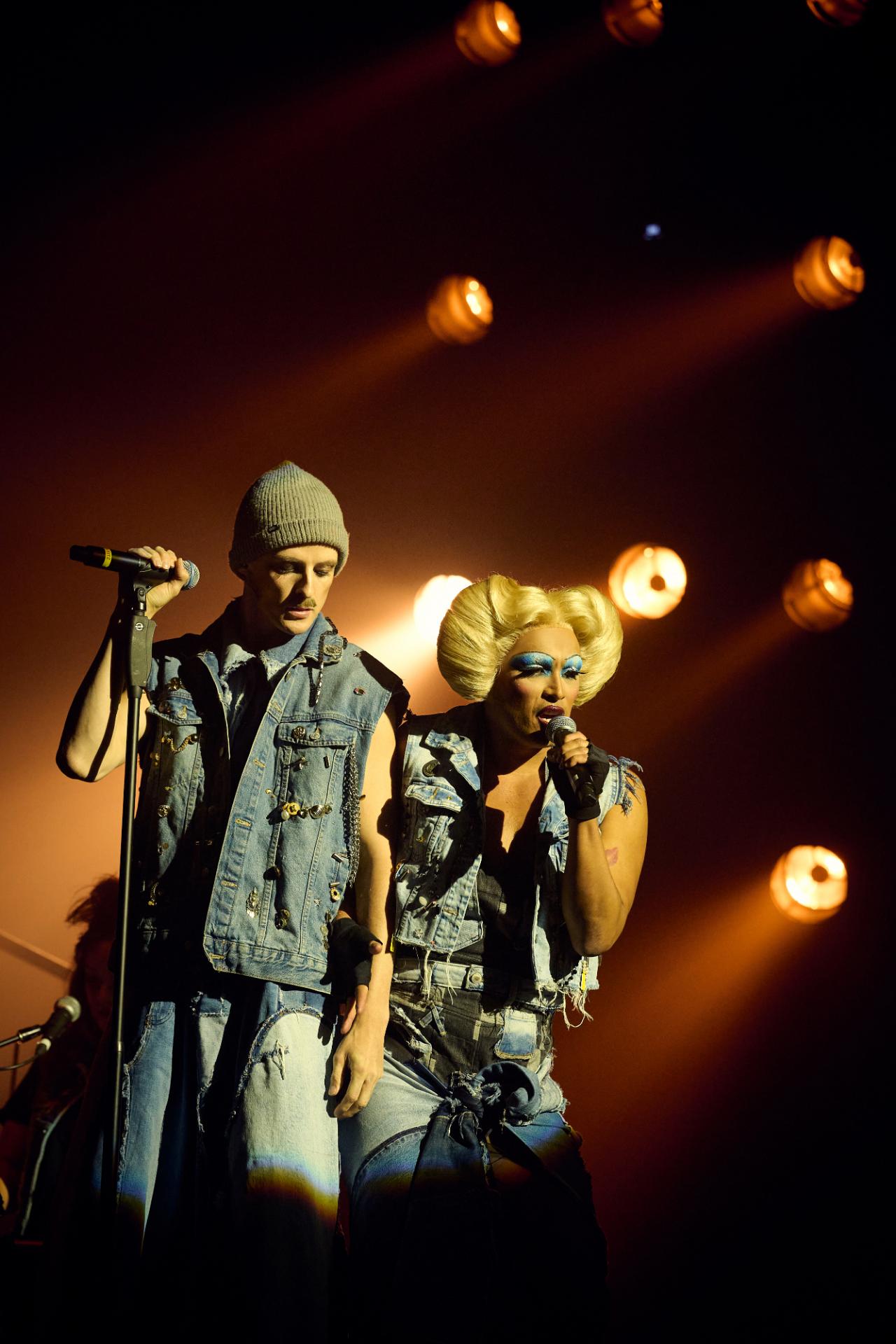

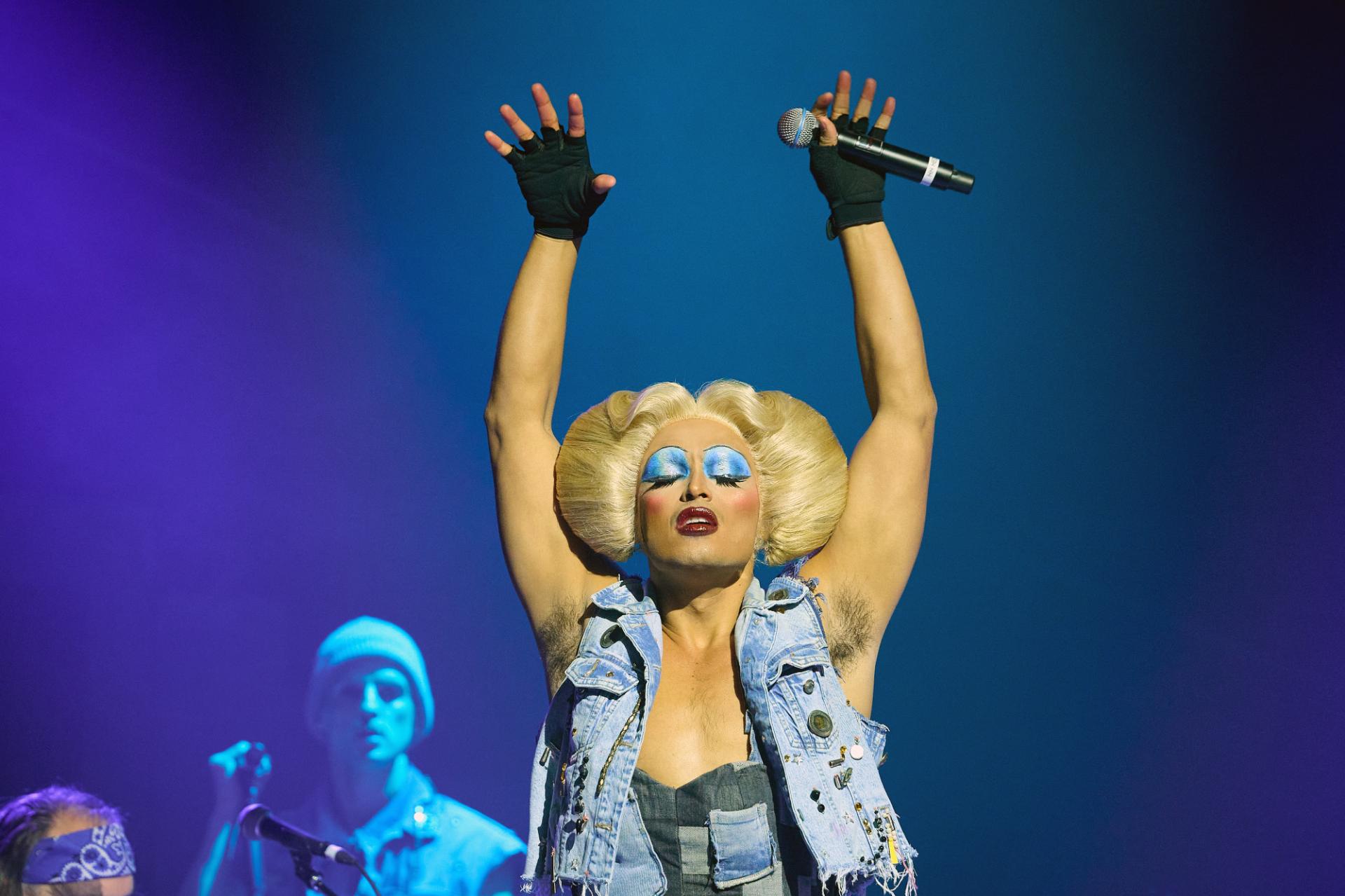

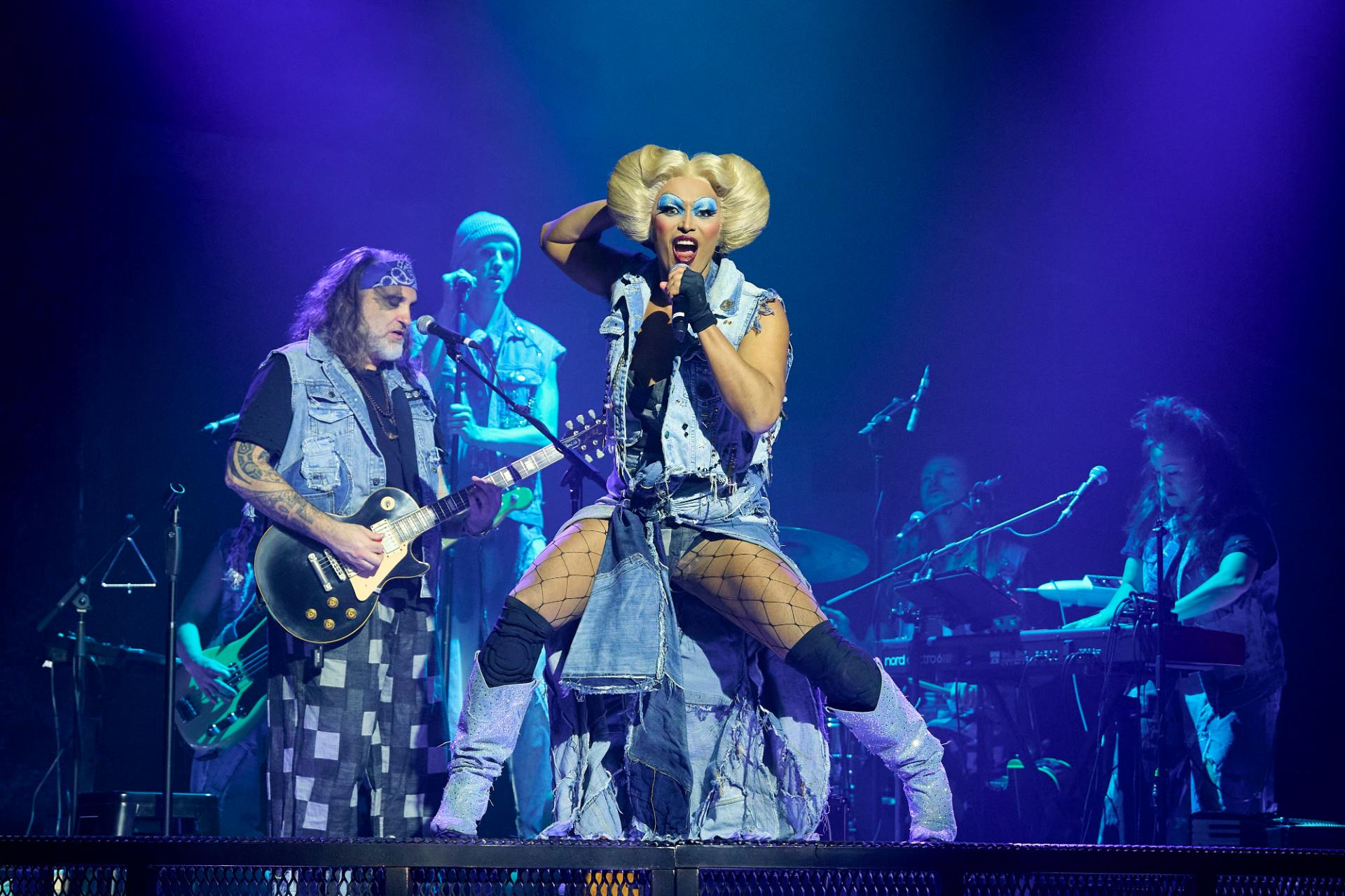

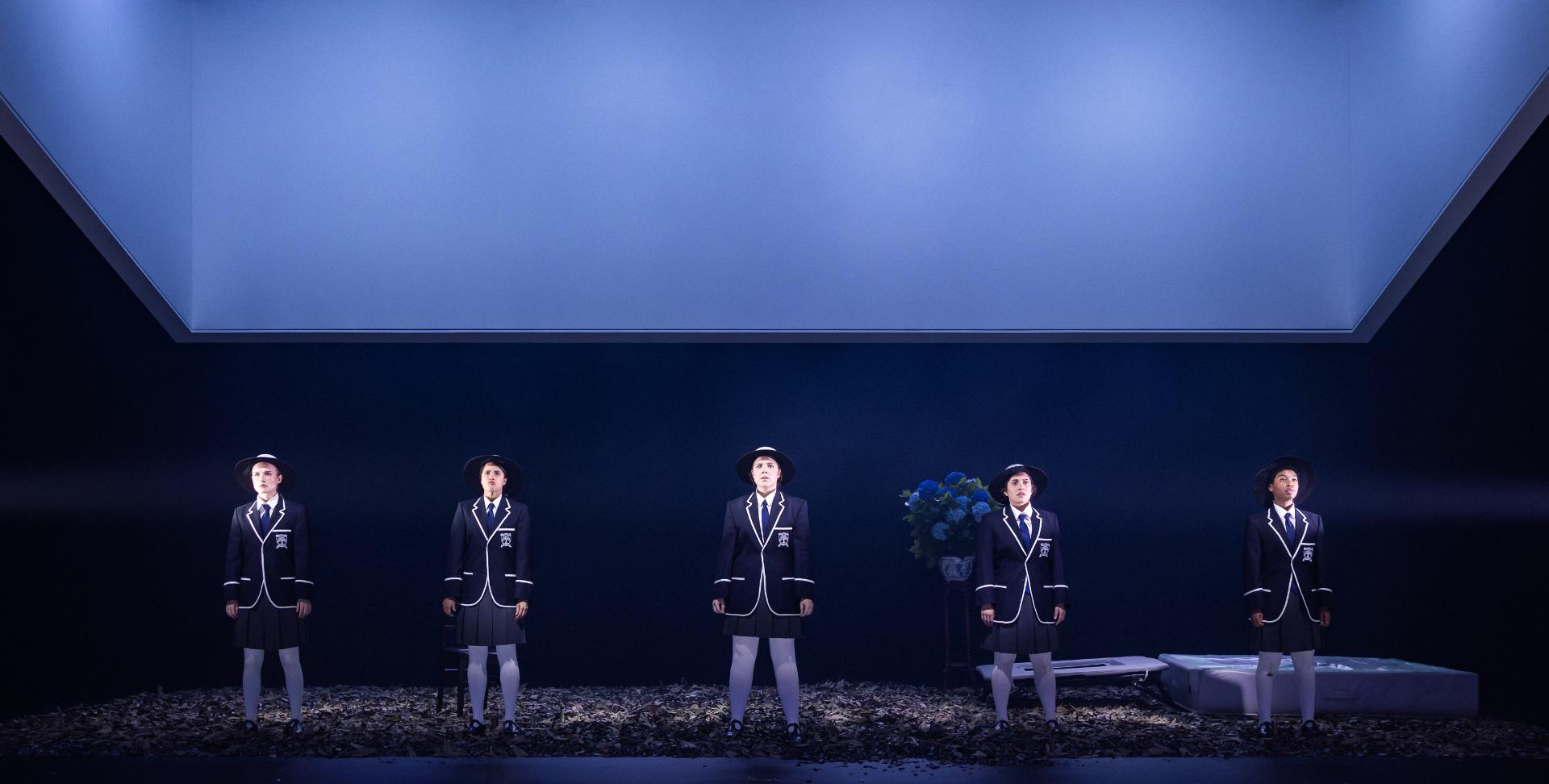

Venue: Carriageworks (Eveleigh NSW), Jan 7 – 18, 2026

Playwright: Travis Alabanza

Director: Sam Curtis Lindsay

Cast: Travis Alabanza

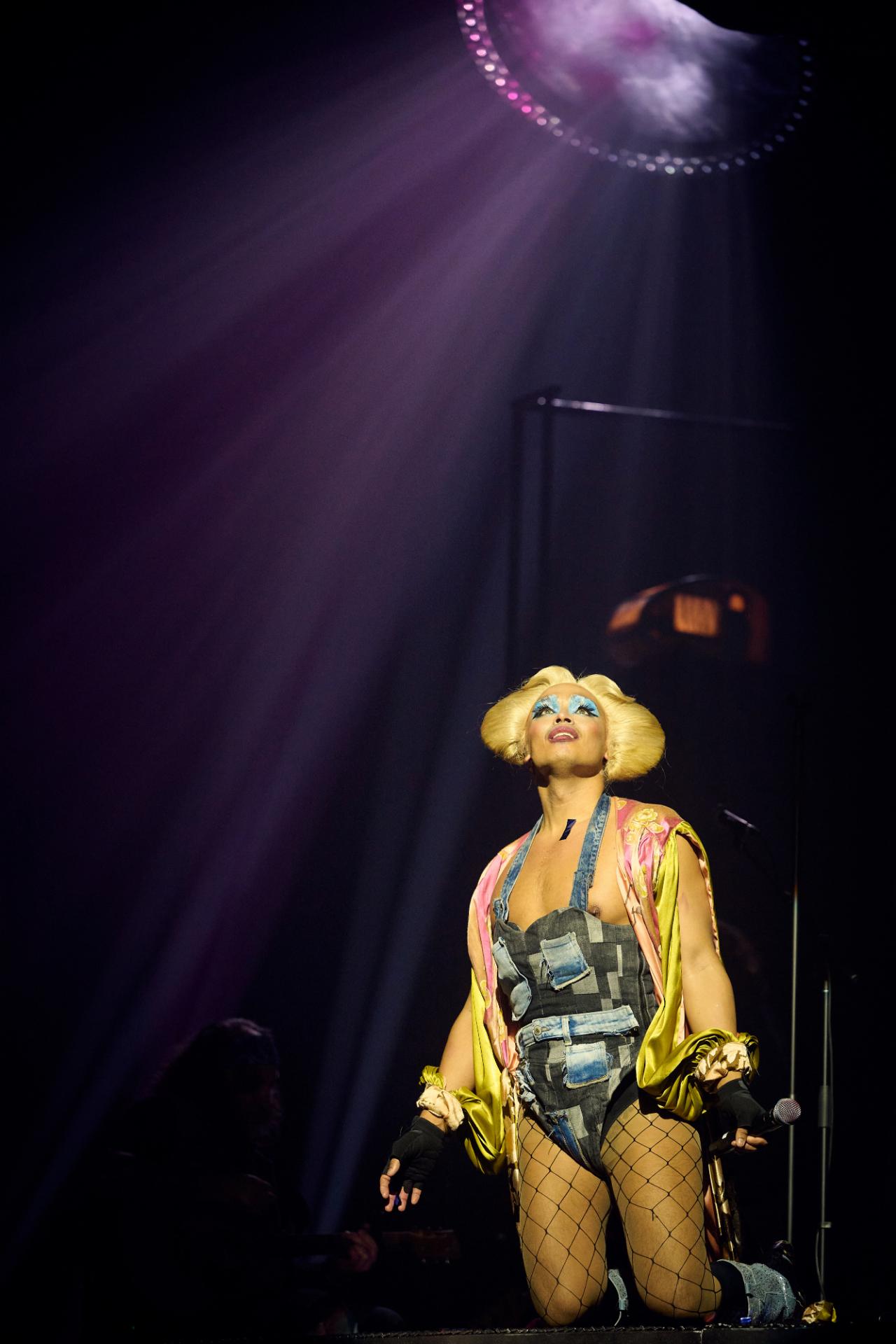

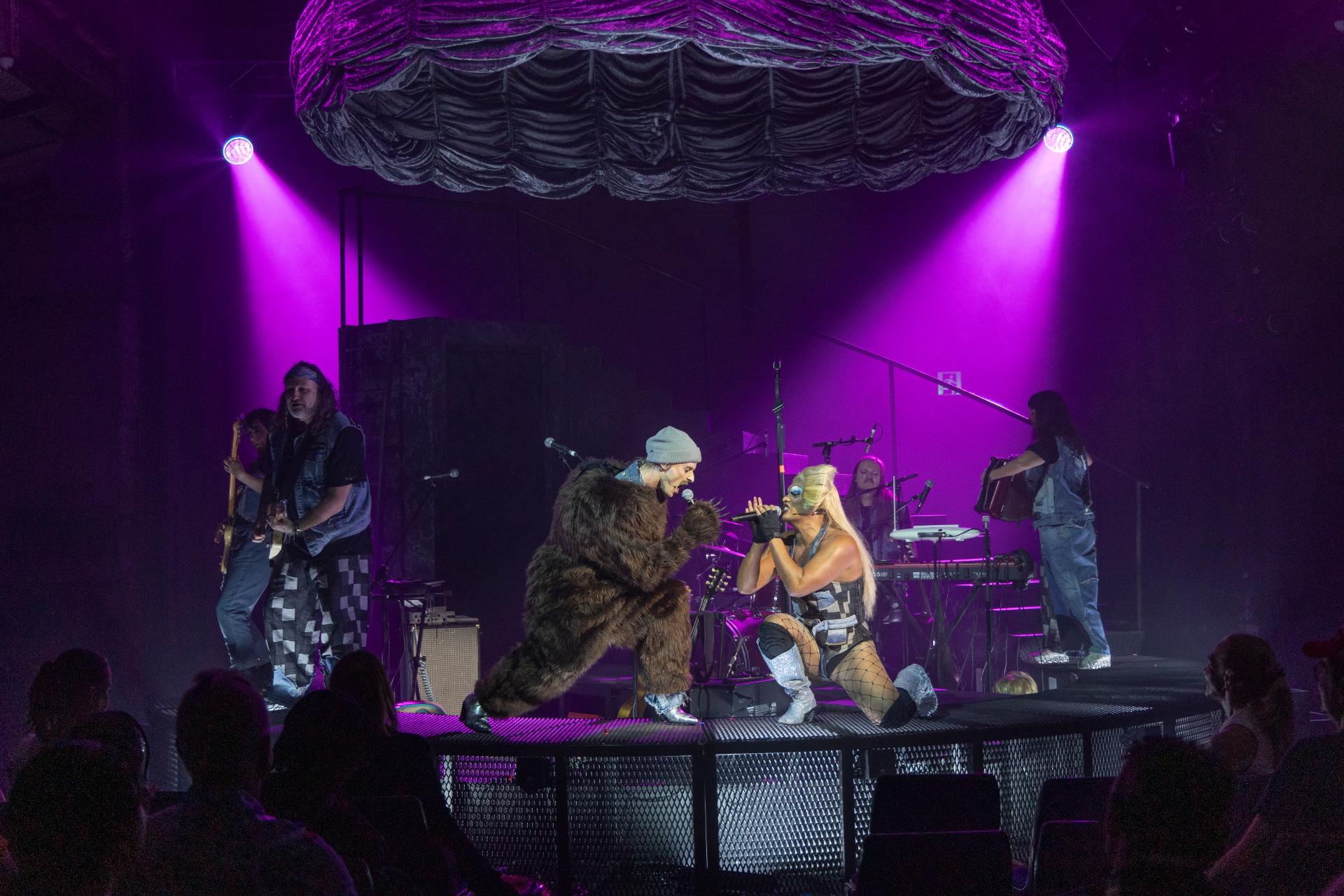

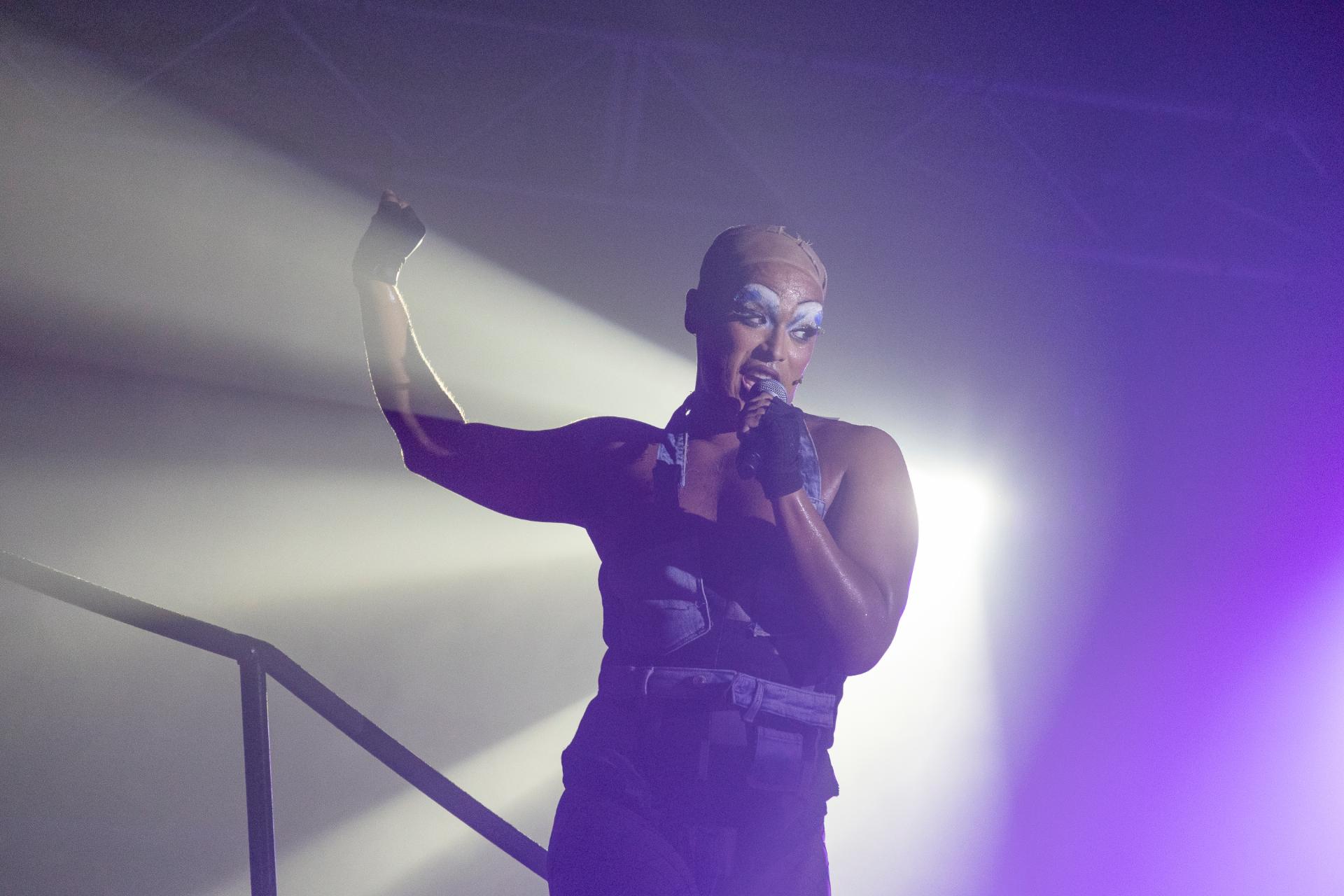

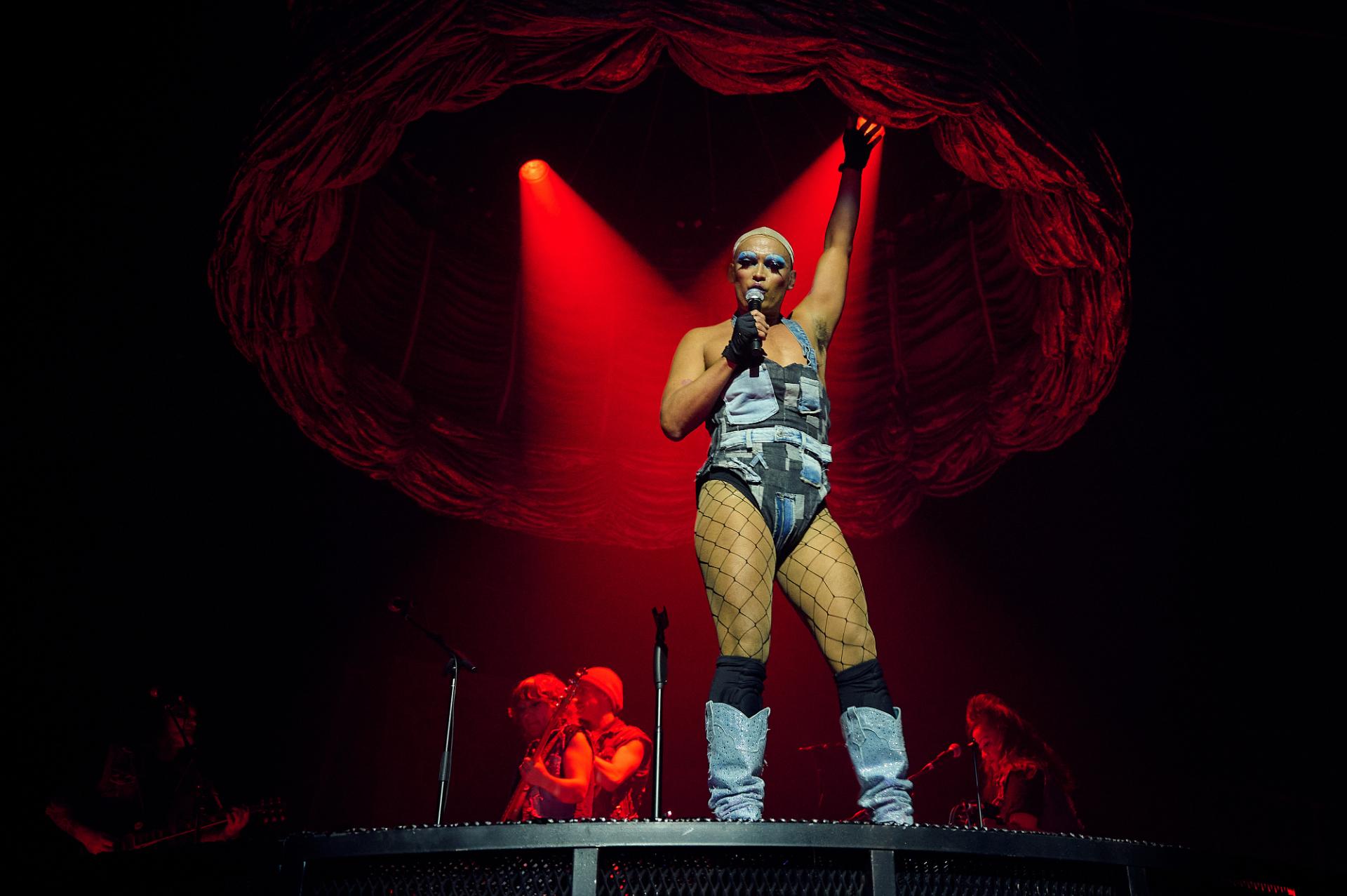

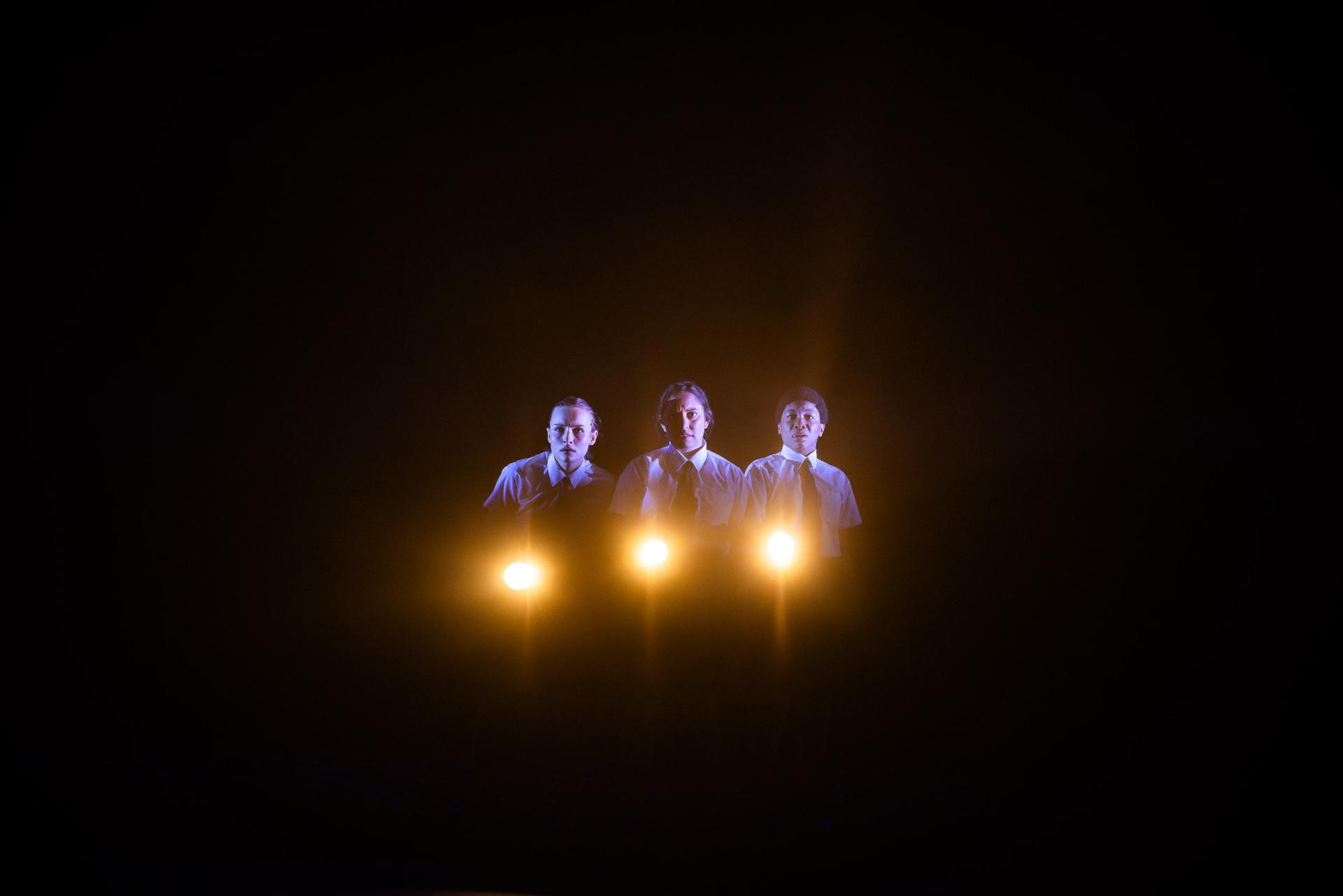

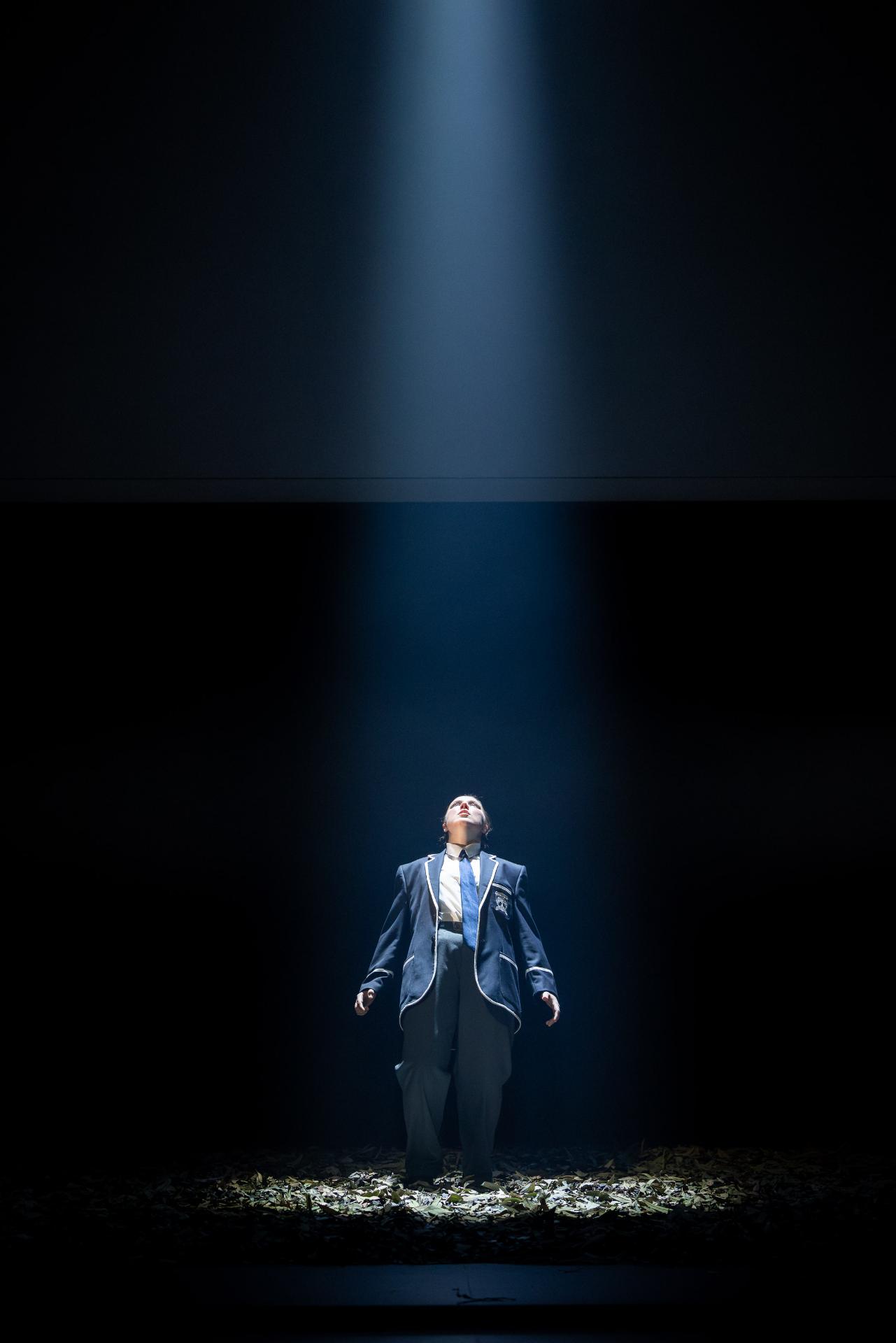

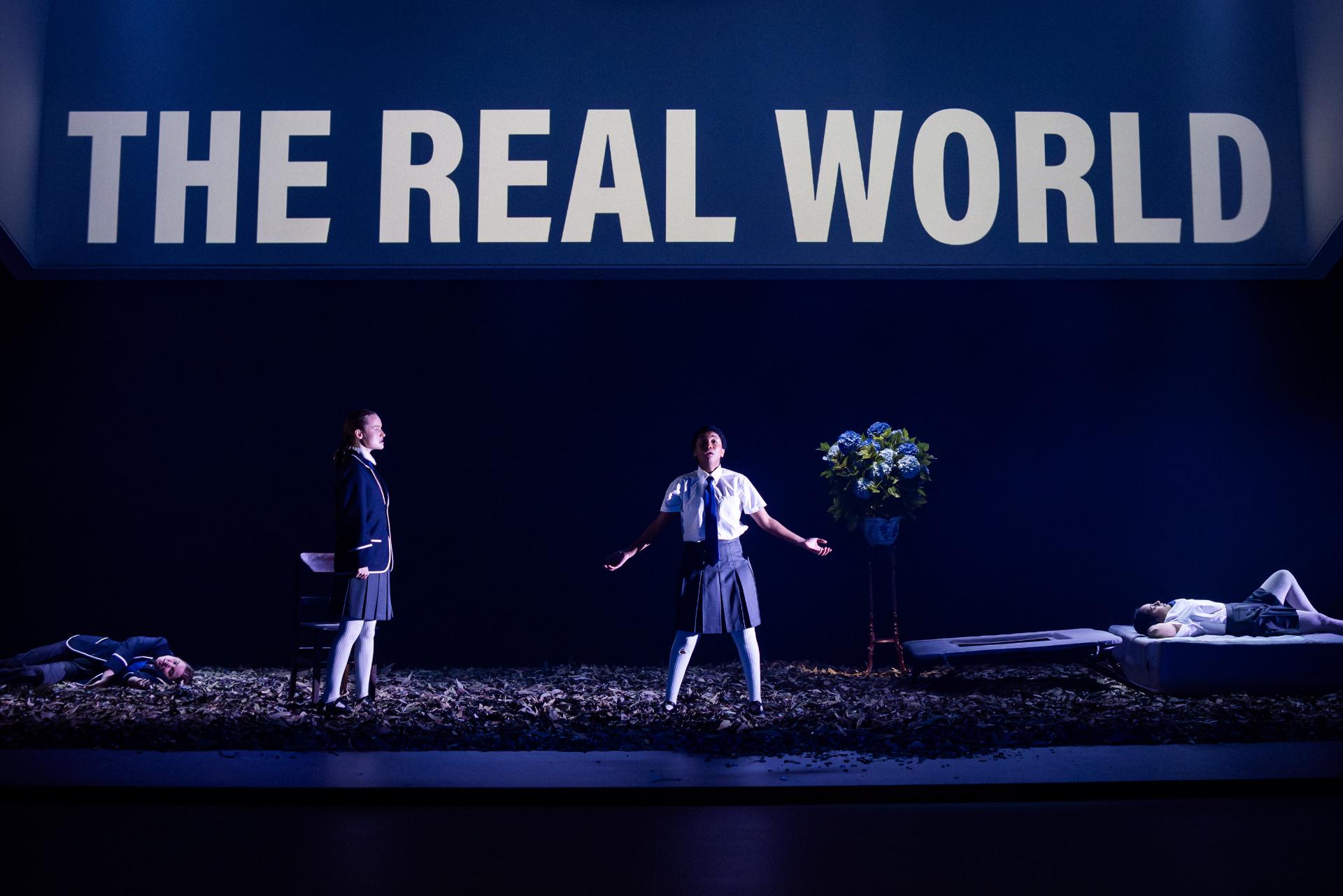

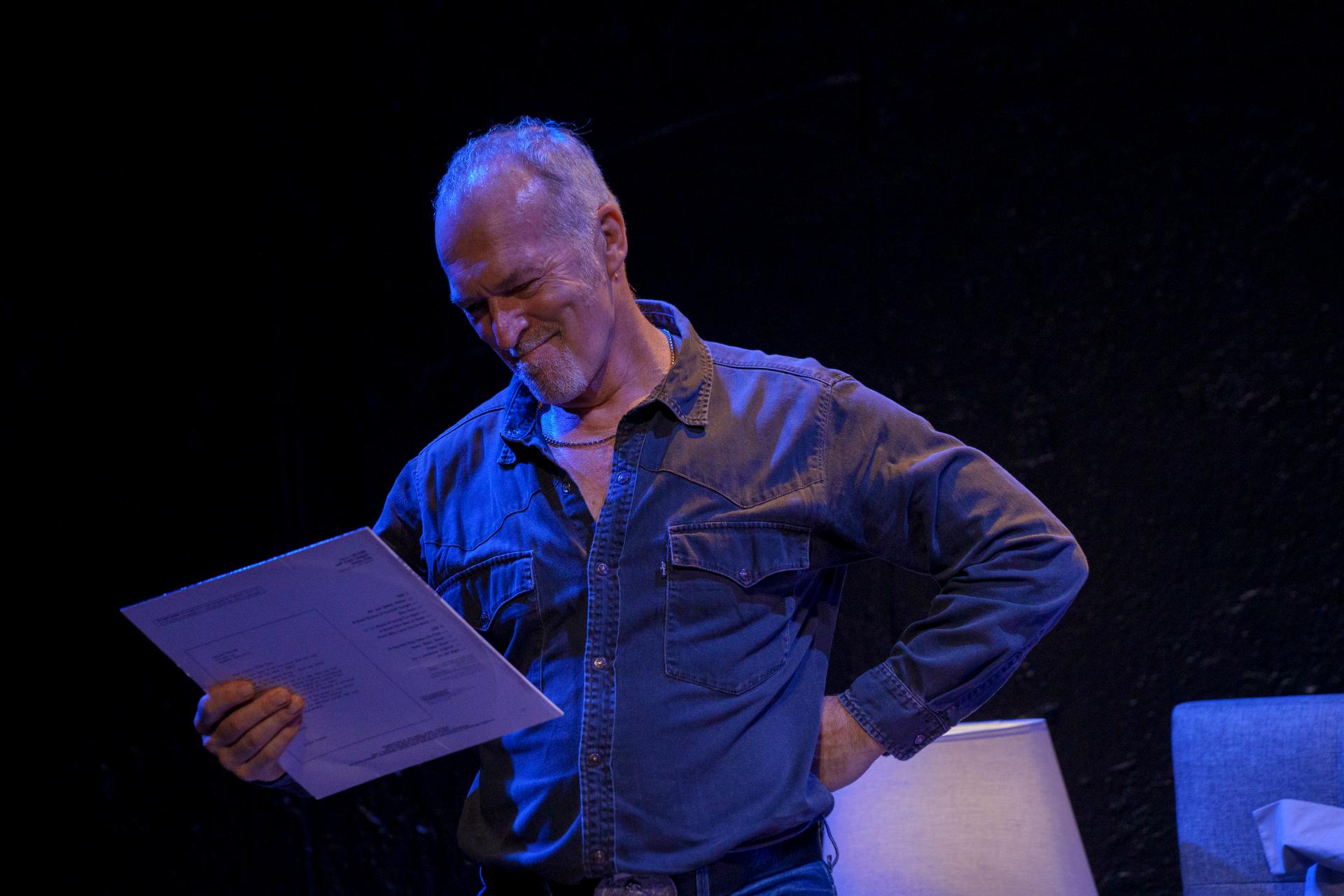

Images by Dorothea Tuch

Theatre review

Travis Alabanza embarks on the deceptively simple task of making their first burger, a venture that is daunting from its very inception. Expectations loom large: rules to be followed, standards to be met, and a destination already mapped out for a journey that has barely begun. Conscious of the weight of these prescriptions, Alabanza invites a volunteer to join them on stage—specifically a straight white man. The choice is pointed rather than incidental, reflecting the reality that so many of the rules governing our lives, both in the UK where the work originated and here in Australia, are institutionalised by those who fit precisely that description.

A work that confronts both trans identity and lived experience as a person of colour, Burgerz is scintillating theatre that embeds danger at its very core. The volunteer does not appear briefly for light-hearted audience interaction; instead, he remains on stage alongside Alabanza for a substantial duration of the performance. This sustained presence heightens a palpable sense that “anything could happen”—a tension that lies at the heart of compelling theatre. More crucially, it mirrors the lived precarity of navigating heteronormative spaces as a trans person of colour, where the possibility of violence is never abstract, but ever-present, hovering in the background of even the most mundane encounters.

The risks Alabanza takes pay off emphatically. Immersed in an unrelenting atmosphere of vulnerability, the audience is held rapt, invested from the opening moments to the final beat. Alabanza’s exquisite wit and disarming charm ensure an unwavering alignment with them, while their intimate command of the material allows each unrehearsed moment of spontaneity—prompted by the surprise presence of a volunteer—to be met with razor-sharp sass and impeccable comic timing. Their capacity to generate genuine chemistry with a stranger is unequivocally extraordinary, resulting in a performance that is both singular and indelibly memorable.

Under Sam Curtis Lindsay’s direction, the work unfolds with instinctive precision, shaping a journey of unexpected texture and continual surprise, one that proves quietly and deeply emotional. The production remains consistently delightful while keeping audiences alert to its shifting rhythms and tonal turns. Soutra Gilmour’s production design embraces a pop-inflected sensibility that complements Alabanza’s signature, calculated flippancy. Lighting by Lee Curran and Lauren Woodhead, together with sound design by XANA, steers the staging through finely calibrated transitions of mood and atmosphere, reinforcing the work’s emotional and theatrical dexterity.

A man once hurled a burger at Alabanza in a public space, an act intended as humiliation and degradation. Alabanza can do everything within their power to reclaim and reframe the incident and its significance, yet a harder truth remains: it is not personal reckoning alone that must shift, but the conditions that permit such acts to occur. We watch Alabanza sink into deep contemplation, meticulously interrogating and dismantling the forces that render the world both resolutely and insidiously exclusionary.

What ultimately comes into focus is an irrefutable understanding that meaningful change requires collective responsibility. We are bound together by the inevitability of shared existence, and the work of recognising—let alone sustaining—one another’s humanity remains the most profound challenge of simply being here.

www.greendoortheatrecompany.com