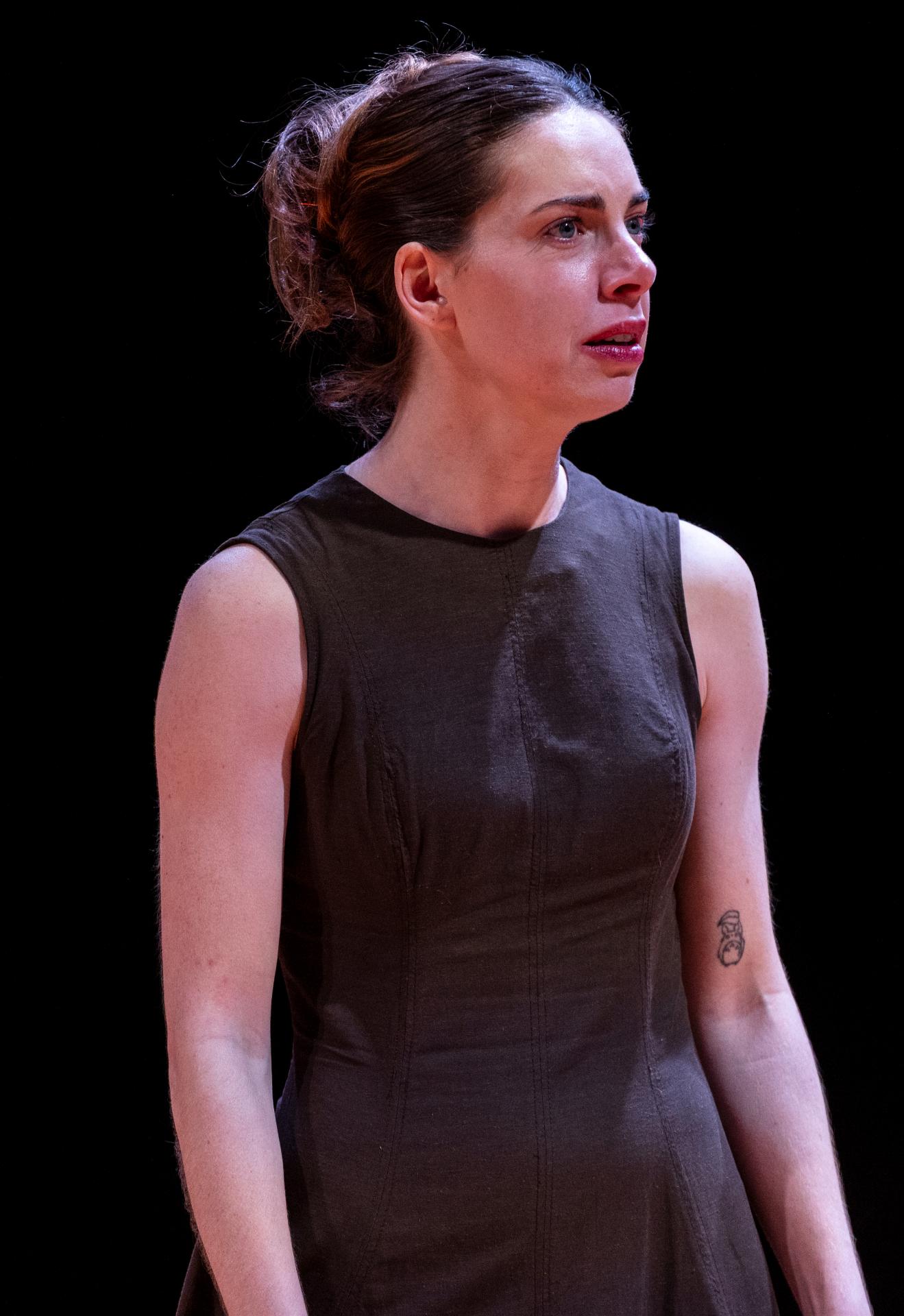

Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Feb 21 – Mar 29, 2026

Playwright: steve j. spears

Director: Declan Greene

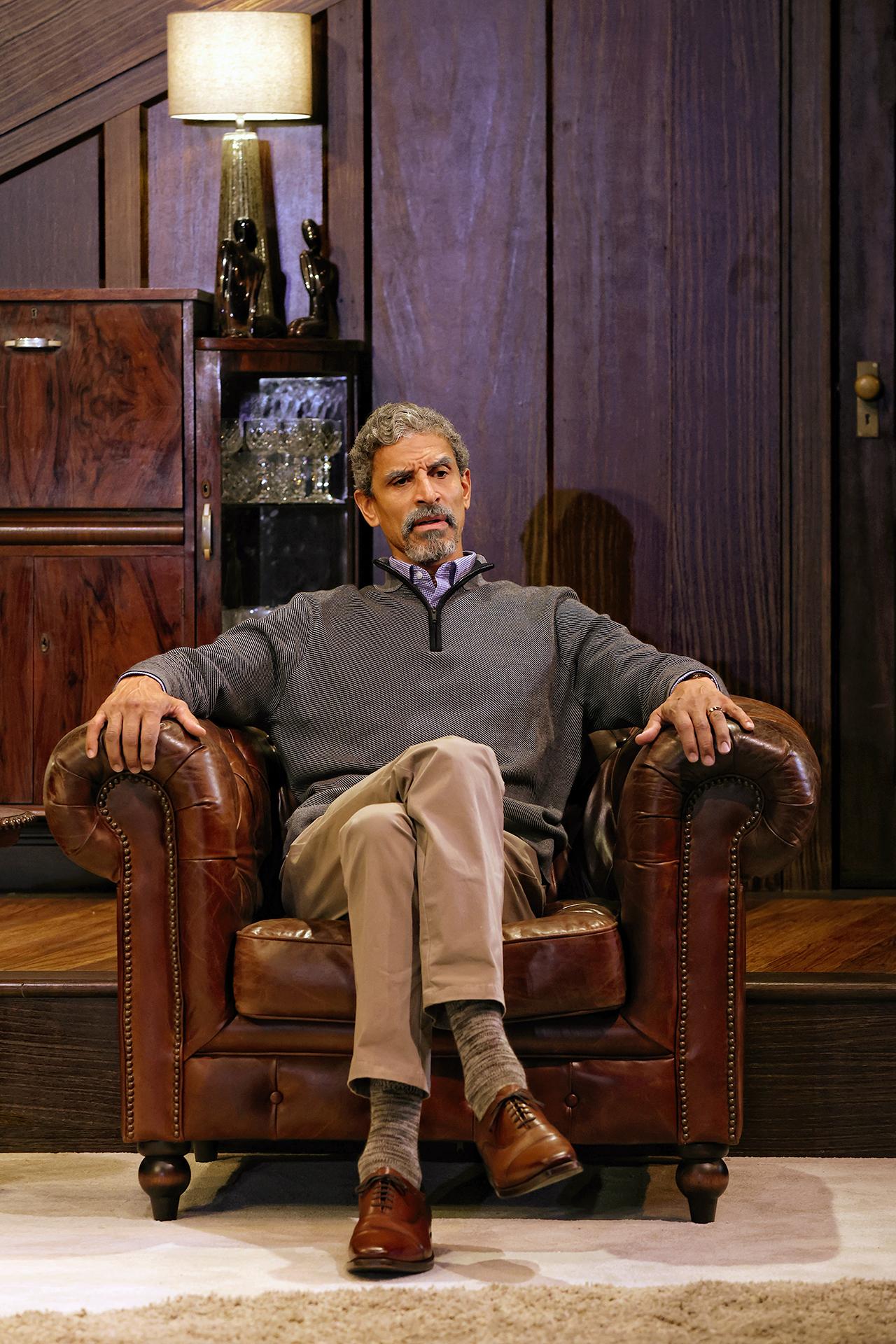

Cast: Simon Burke AO

Images by Brett Boardman

Theatre review

Robert O’Brien leads a life of deliberate seclusion, his world contained within the walls of his home where he devotes himself to the exacting art of vocal pedagogy, instructing pupils across the full spectrum of age and aspiration. The equilibrium of this carefully calibrated existence is disrupted when Benjamin—a twelve-year-old of startling precocity and unsettling sophistication—arrives to reveal himself as nothing short of prodigious. This narrative unfolds in the early 1970s, an era of terrifying peril for all who share Robert’s sexual orientation; even his most careful navigation of social propriety cannot insulate him from the devastating ease with which circumstance may turn into accusation, suspicion into ruin.

Half a century has elapsed since steve j. spears’ The Elocution of Benjamin Franklin inaugurated its world premiere upon the Sydney stage, and while the landscape of queer liberation has undergone transformation beyond measure, the play’s explorations of intolerance, prejudice, and bigotry remain as piercingly relevant as ever—a testament to the uncomfortable truth that while laws may evolve, the fundamental human capacity for cruelty and hate often endures.

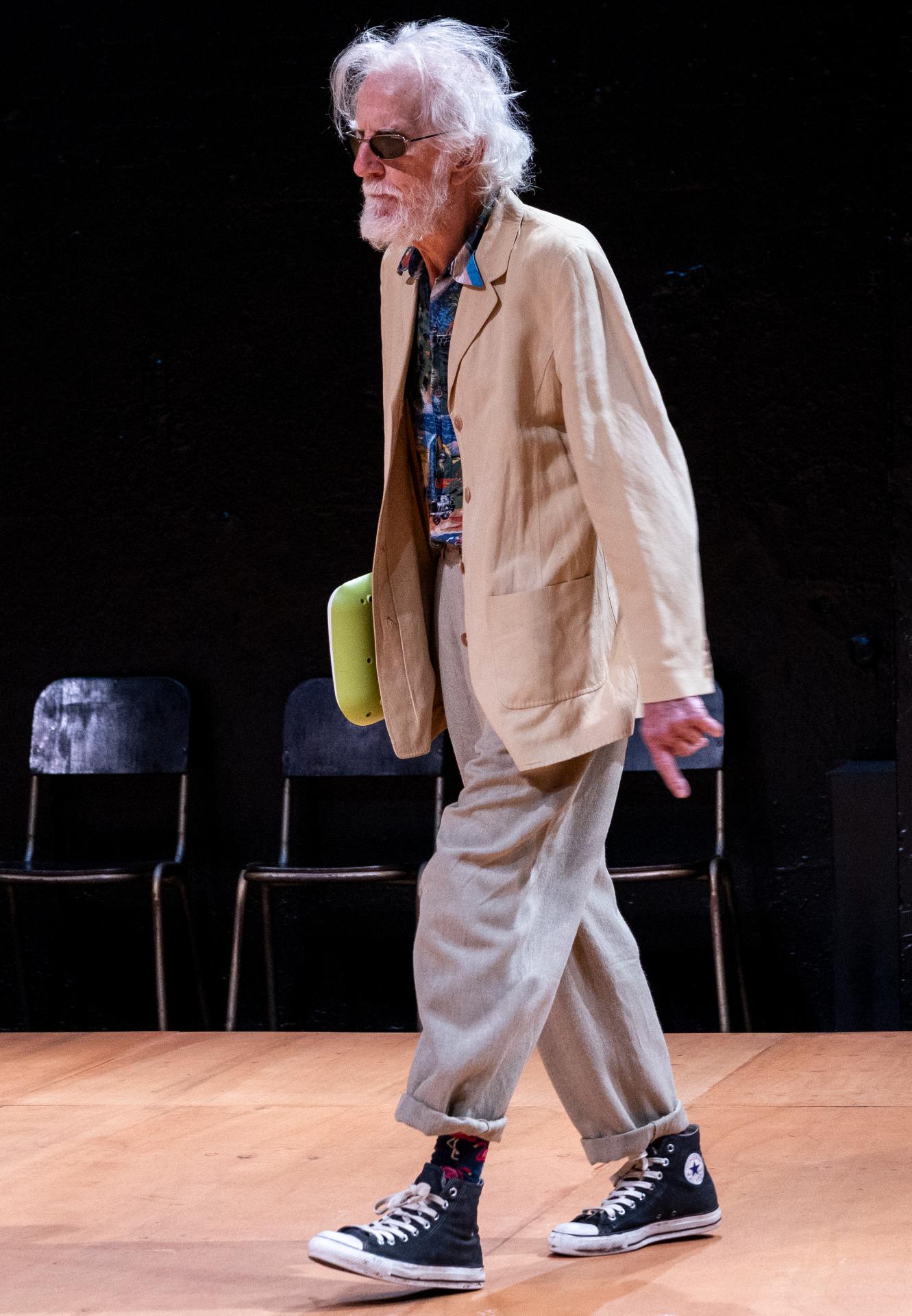

Under Declan Greene’s direction, the production carries an unmistakable reverence—a profound acknowledgment of a generation for whom queerness meant navigating a world far more hostile than today’s youth might readily comprehend. The work functions, quite clearly, as homage to those forebears and elders who charted paths through terrain that could, at any moment, turn treacherous. Yet the production never settles into mere period tribute; it remains astutely attuned to the present, using its historical lens to examine the seemingly cyclical nature of persecution and the ease with which any minority can become scapegoat du jour. The Elocution of Benjamin Franklin ultimately wields considerable power in its address, even as its dramatic traction proves somewhat uneven—with individual scenes varying in their capacity to compel as the narrative unfolds.

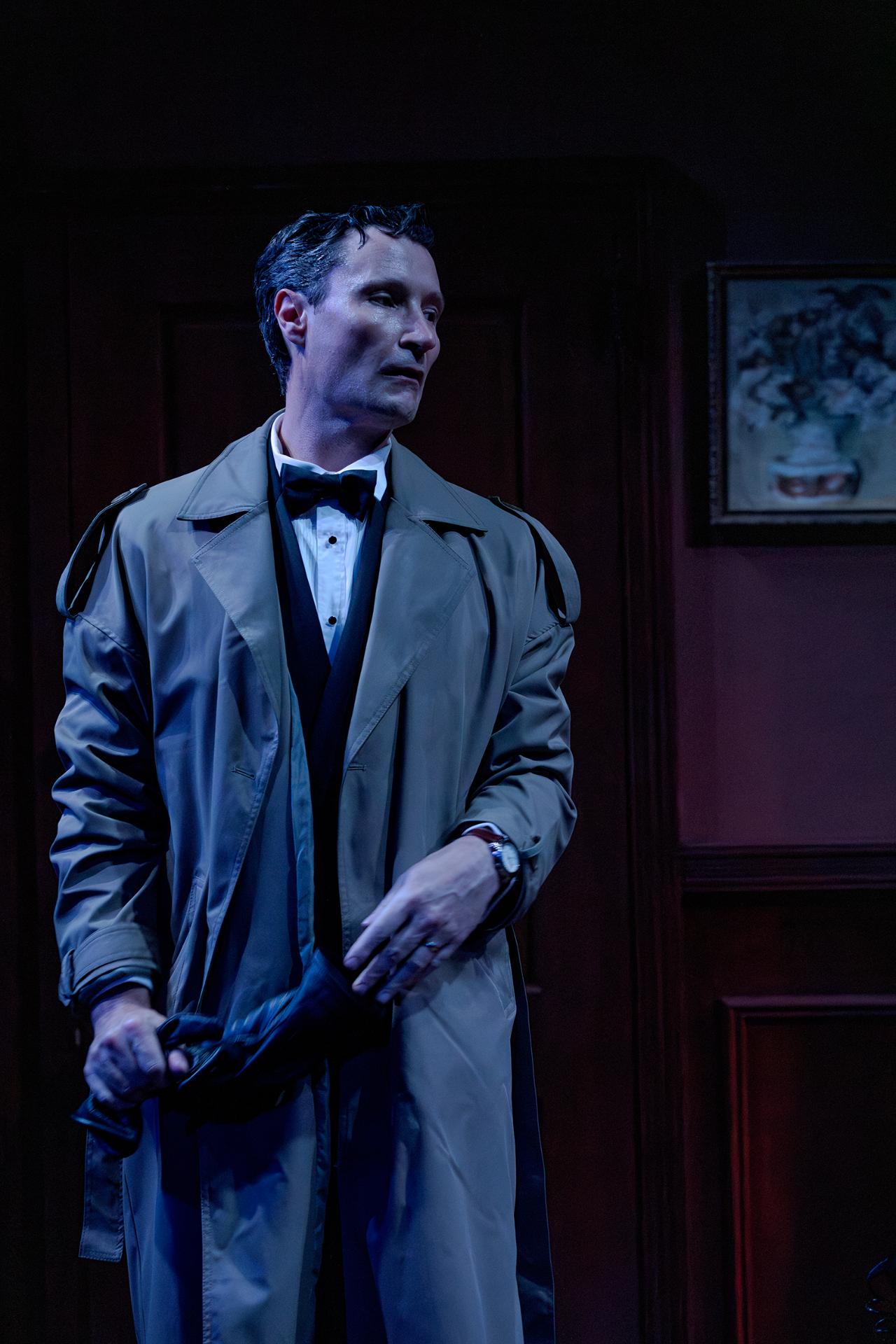

Isabel Hudson’s production design conjures a genteel nostalgia—an aesthetic meditation upon queer history that attends with equal sensitivity to the elegiac allure being manufactured and to the precariousness underlying its surface. Lights by Brockman prove instrumental in choreographing our temporal passage, whether languorous or abrupt; its mercurial unpredictability generates a distinctly satisfying theatrical frisson. Working in intimate concert, David Bergman’s sound and music prove equally indispensable, enabling the production’s transcendence of material realities to reach the essential core of its thematic concerns.

Simon Burke AO delivers a performance of remarkable depth and emotional acuity in his portrayal of Robert. Whether navigating registers of flippant vivacity or mortal gravity, he maintains a presence at once reassuring and undeniably sincere—radiating a warmth that secures our attentive vulnerability, rendering us receptive to the excavation of a queer historical epoch that demands our permanent remembrance.

Just when one might have reasonably supposed our community could begin to shift its focus from old battles to new horizons, these last forty-eight hours have delivered via the news, harrowing accounts of violence against young gay men—assaults whose contours bear chilling resemblance to those that recurred with grim regularity before decriminalisation, before marriage equality, before any number of legislative milestones we imagined might signal lasting change.

It is clear that legal frameworks, however essential, cannot alone dismantle the deeper machinations of prejudice. The same streets that witnessed violence decades ago continue to witness it still; the same fear that coursed through gay men navigating public space in the previous century courses through their counterparts today. Progress, for all its genuine achievements, does not move in an unbroken forward trajectory. It stalls, it falters, and sometimes it reveals itself to be far more fragile than we wish to believe. Hate crimes against queer people are not anachronisms—they are the present, demanding we reckon with how much remains undone.