Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Jul 12 – 19, 2023

Book, Music and Lyrics: Jules Orcullo

Director: Amy Sole

Cast: Jules Orcullo, Nova Raboy

Images by Clare Hawley

Theatre review

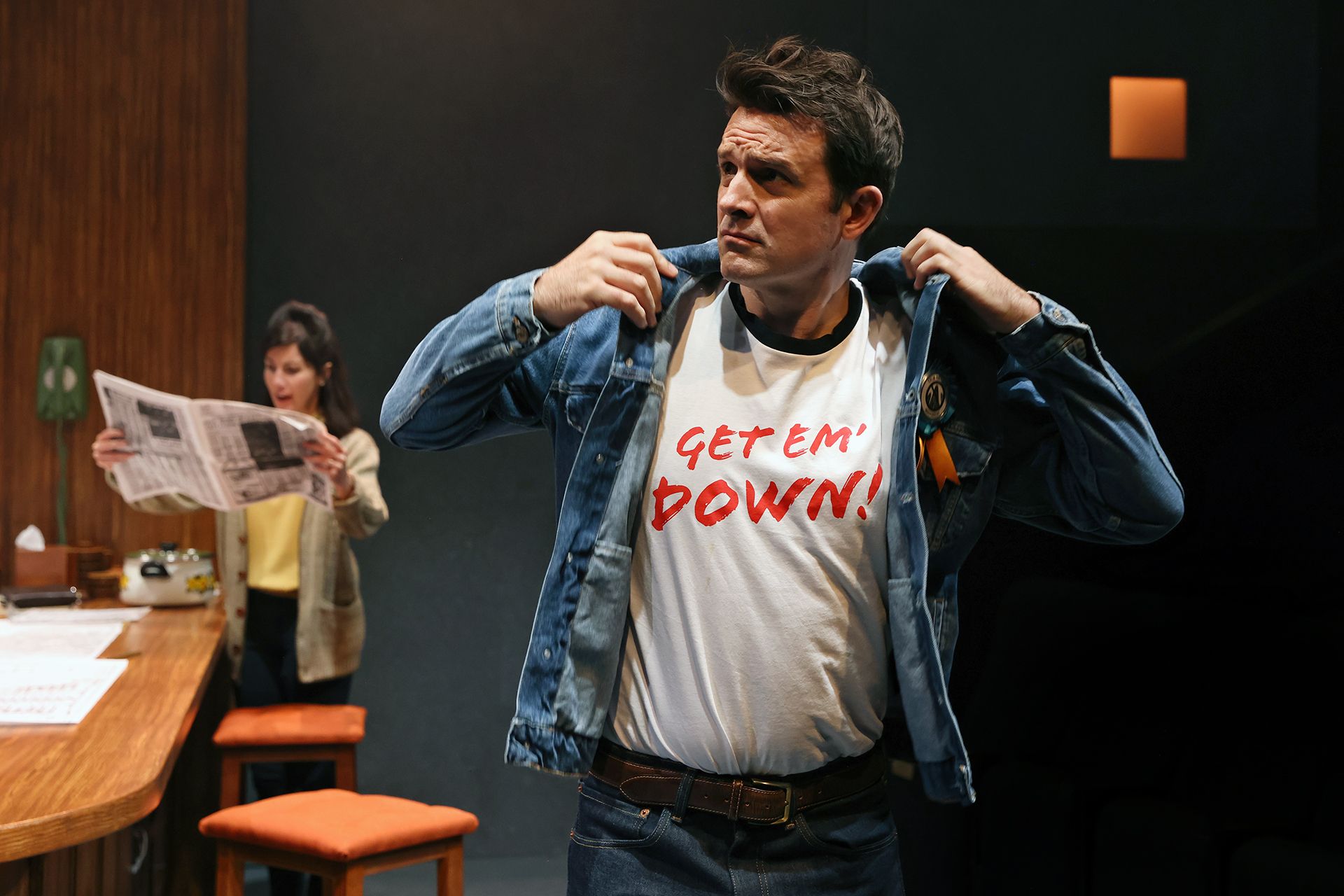

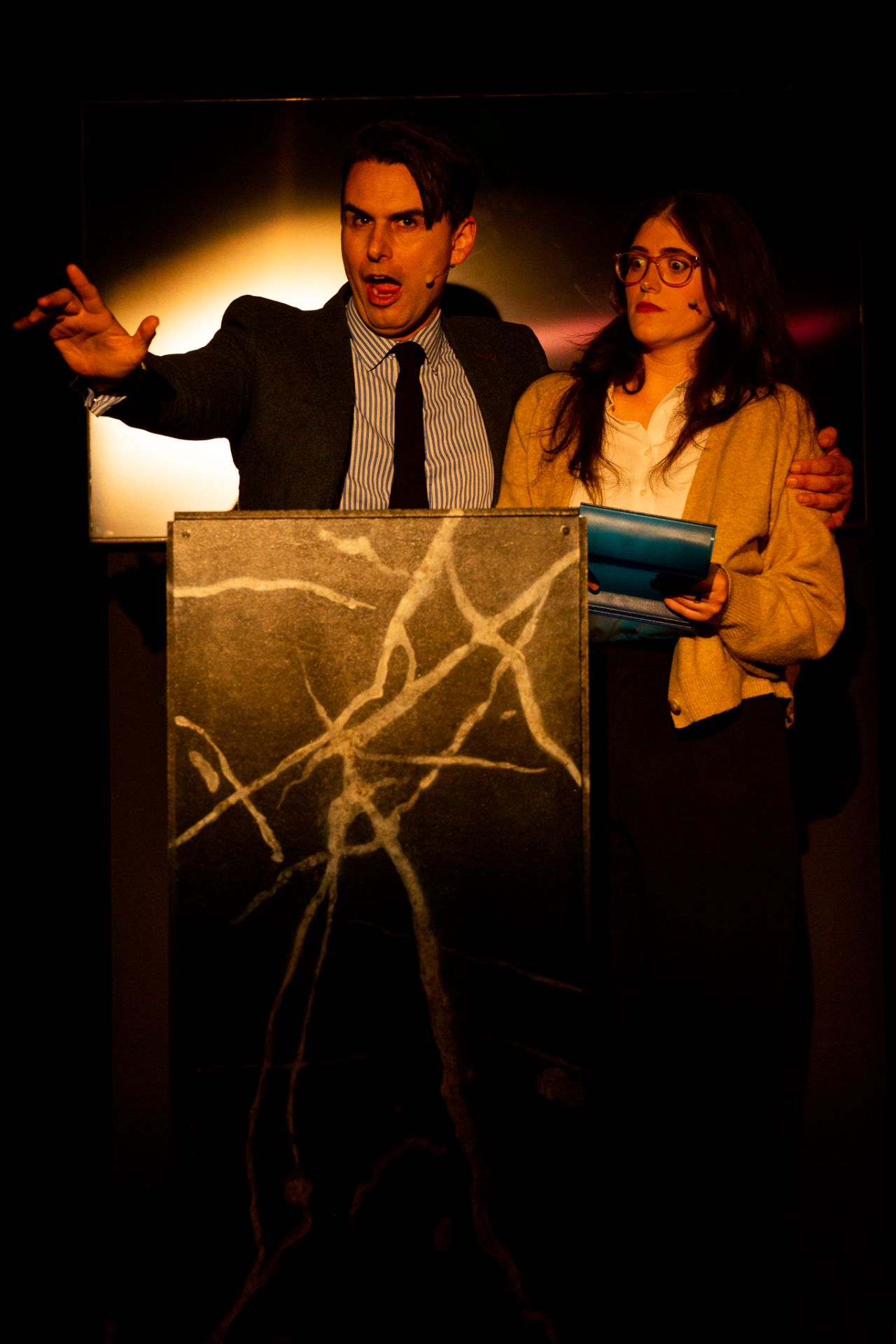

Jules quit her job and moved home during the pandemic, thinking she would take the opportunity to really develop her art. Just when she becomes exasperated about the lack of progress, an accidental social media post exposes her talent to childhood idol Tim Minchin, and things begin to magically fall into place. Jules Orcullo’s original musical Forgetting Tim Minchin is a deeply whimsical work, full of genuine hilarity, juxtaposed against an unrelenting and disarming commitment to emotional authenticity. Despite its creator’s many reminders that the story is mostly fictional, the musical captivates seemingly effortlessly, with its enchanting blend of comedy and heartfelt moments.

The show is hugely entertaining, directed by Amy Sole whose detailed approach ensures an extraordinary attention to nuance, so that we are seduced into the tiny microcosm of Jules’ bedroom, where a world of imagination and passion is allowed to flourish. Set and costume design by Hailley Hunt are rendered with accuracy, for familiar imagery that speaks on where and who the characters are, in both geographical and socio-economic terms. Lights by Kate Baldwin offer meaningful transformations of space, transporting us across various degrees of reality.

Most of the musical accompaniment is pre-recorded, and although arranged in the simplest style, the songs are never any less than thoroughly delightful. Along with a sound design by Christine Pan and musical direction by Andy Freeborn, all that we hear in this musical production, endears us to its central characters, making us understand and care for them, at every moment.

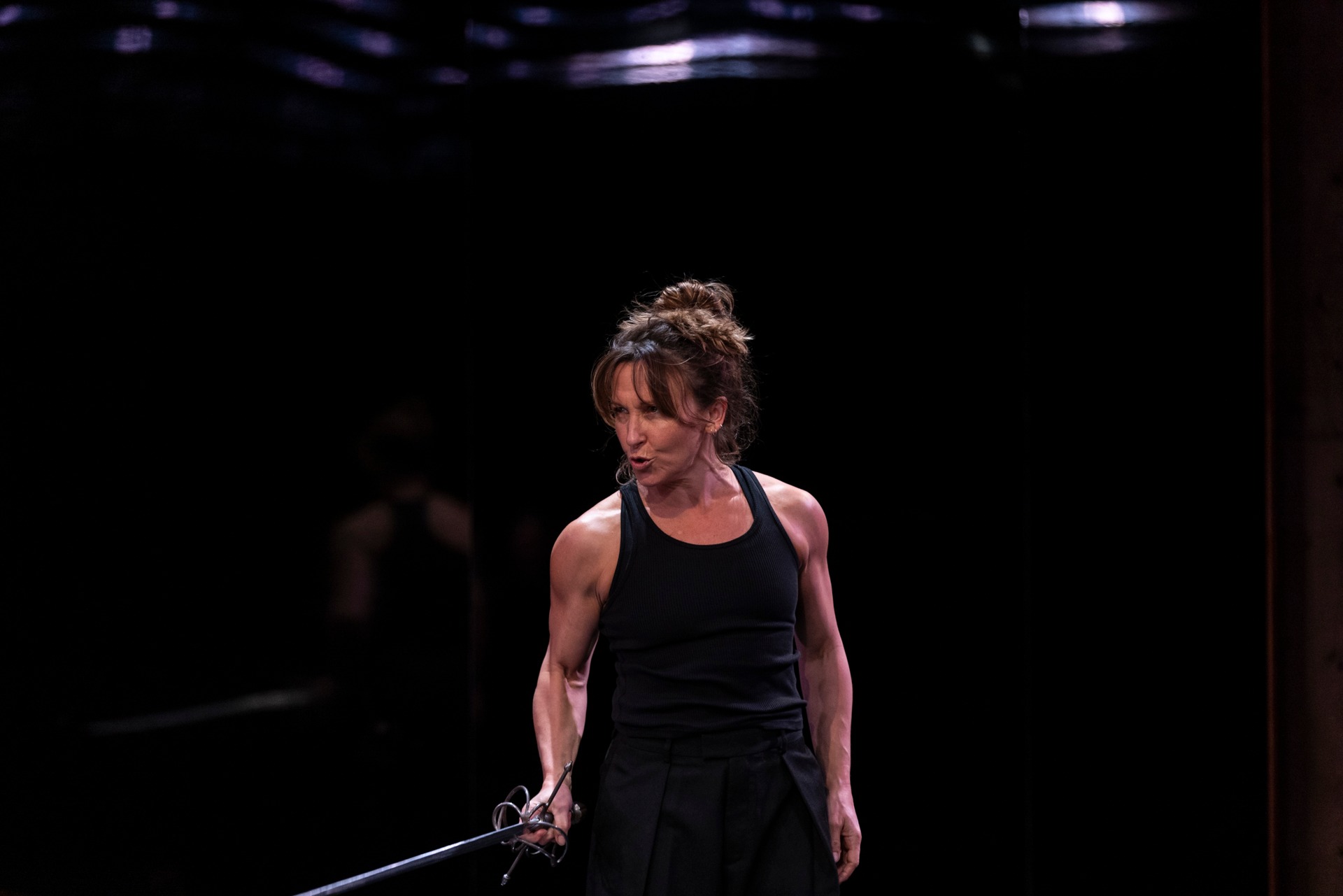

As performer, Orcullo is a magnetic presence, with an ability to access a certain inner truth, that makes her audience defenceless and entirely open to whatever may come, in this unpredictable journey. Playing Jules’ mother is Nova Raboy, whose remarkable capacity for tenderness and warmth, draws us further into the storytelling. Movement direction by Lauren Nalty gives both performers a sense of structured form and discipline to their physicality, to imbue a visual finesse that further elevates the production.

Forgetting Tim Minchin delivers laughter and tears, in copious amounts. It is an opportunity for emotional catharsis, but probably more importantly, it is an exercise in empathy at a time when we feel increasingly persuaded to become hardened and unfeeling. Orcullo’s work showcases a vulnerability that modern life is rarely capable of accommodating, yet is unequivocally intrinsic to the human experience, and foolish of us to neglect. With computers poised to take over every mechanical aspect of our existence, we should perhaps consider a great retreat into the essentially constitutive human materials, of flesh and spirituality; learn anew to celebrate an attention to vulnerability, and begin to strip off generations of cladding enclosed around it, leave behind what was meant to protect, but have inadvertently made us increasingly inhuman.