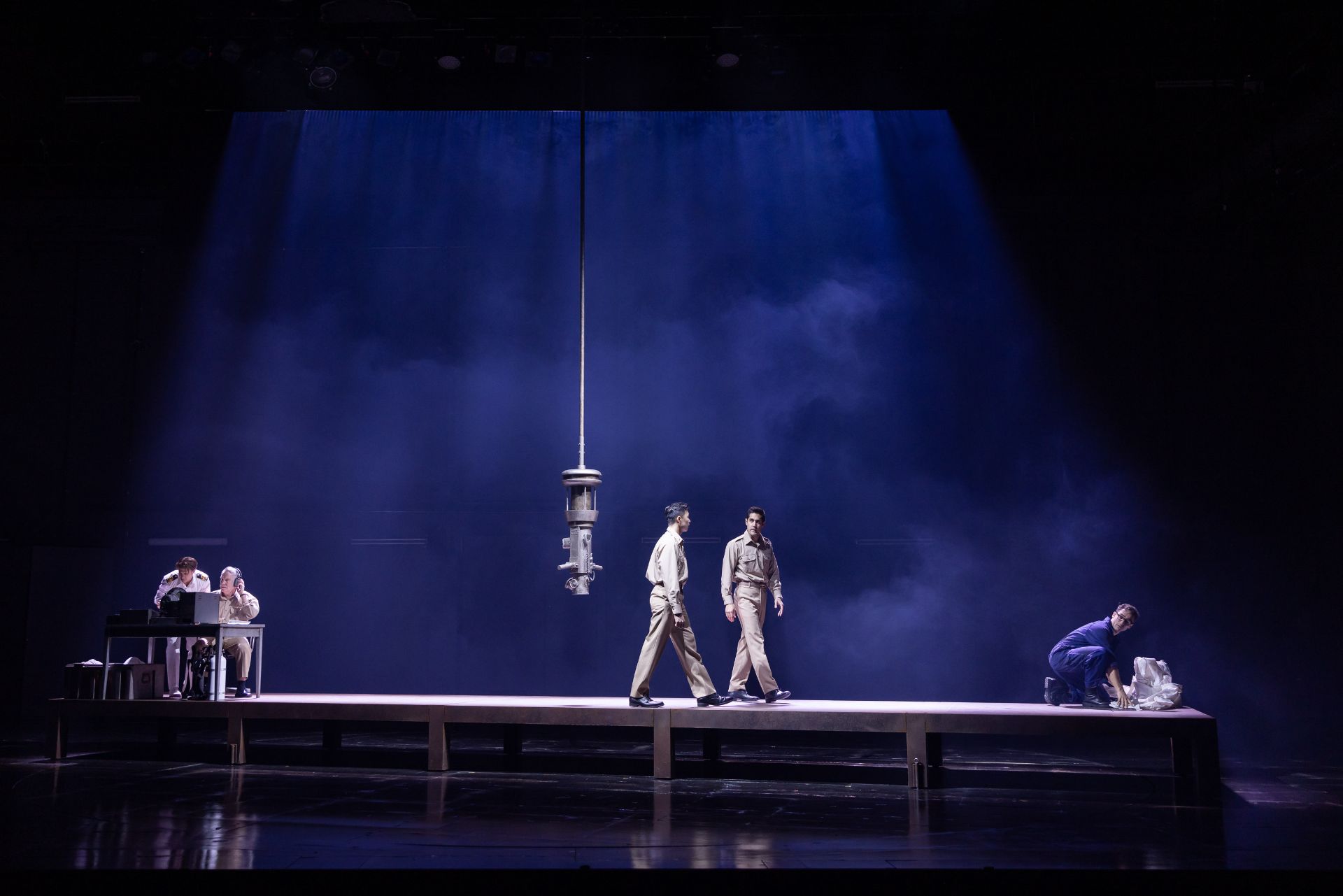

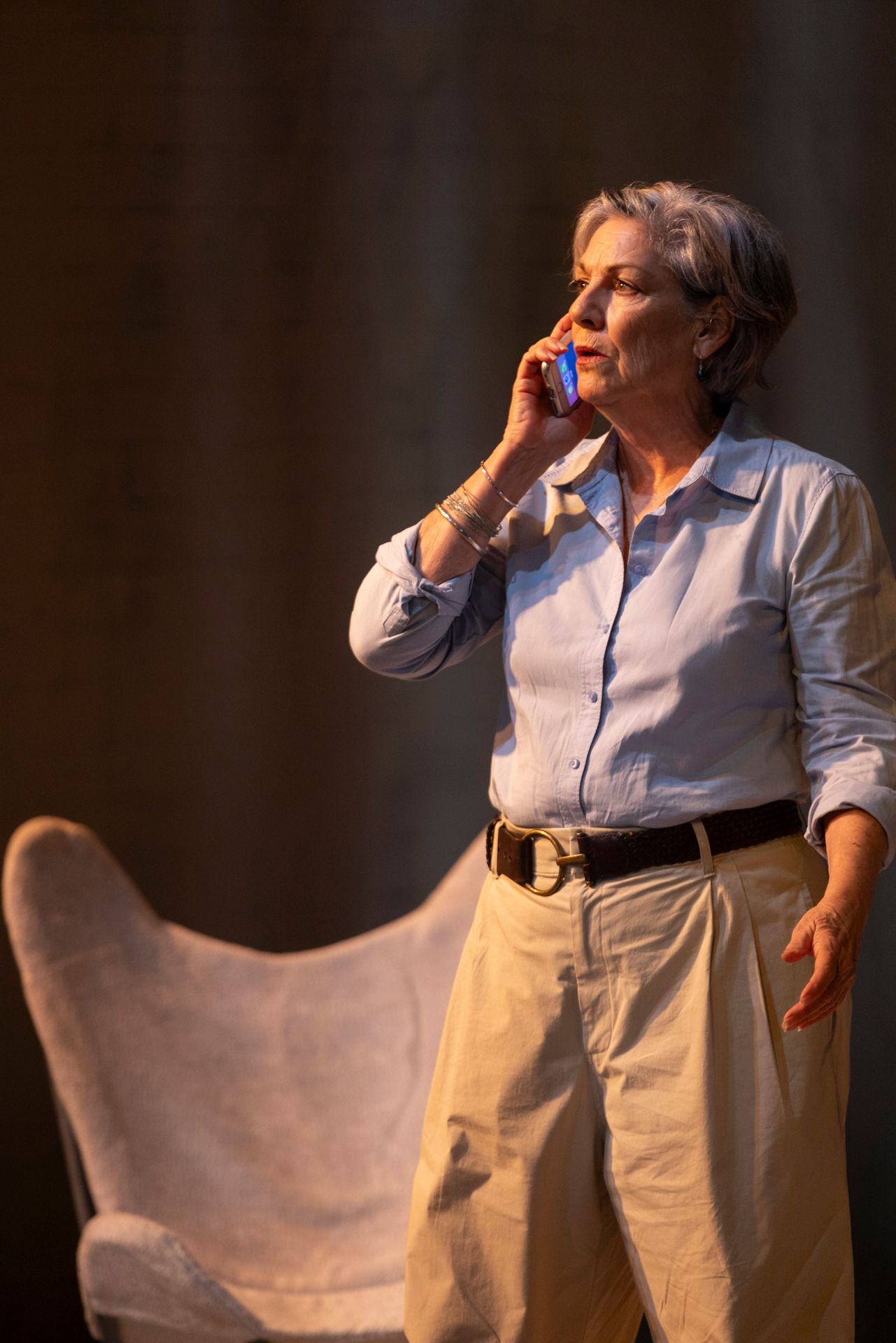

Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Aug 5 – Sep 10, 2023

Playwright: Sue Smith (based on the novel by Charlotte Wood)

Director: Sarah Goodes

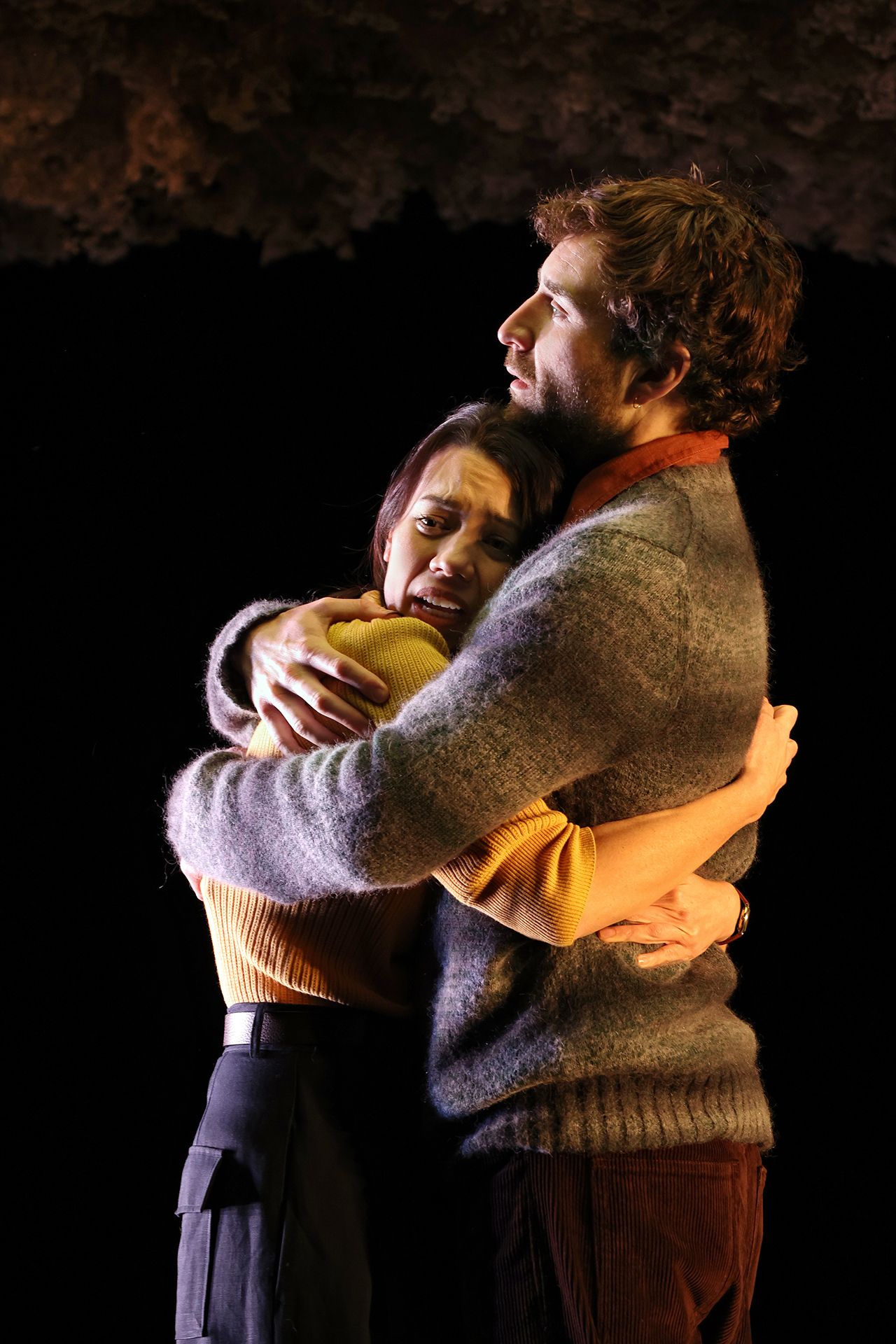

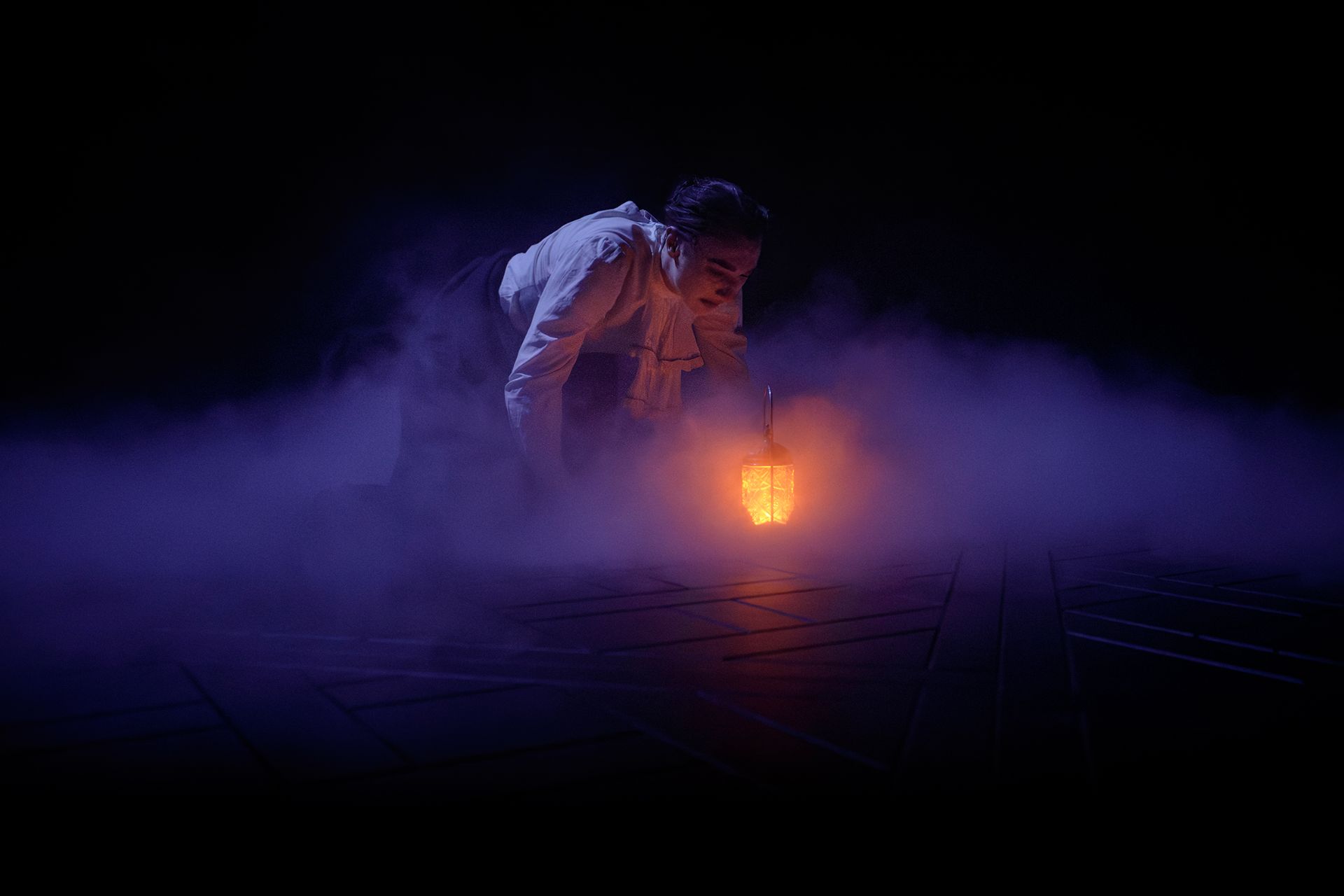

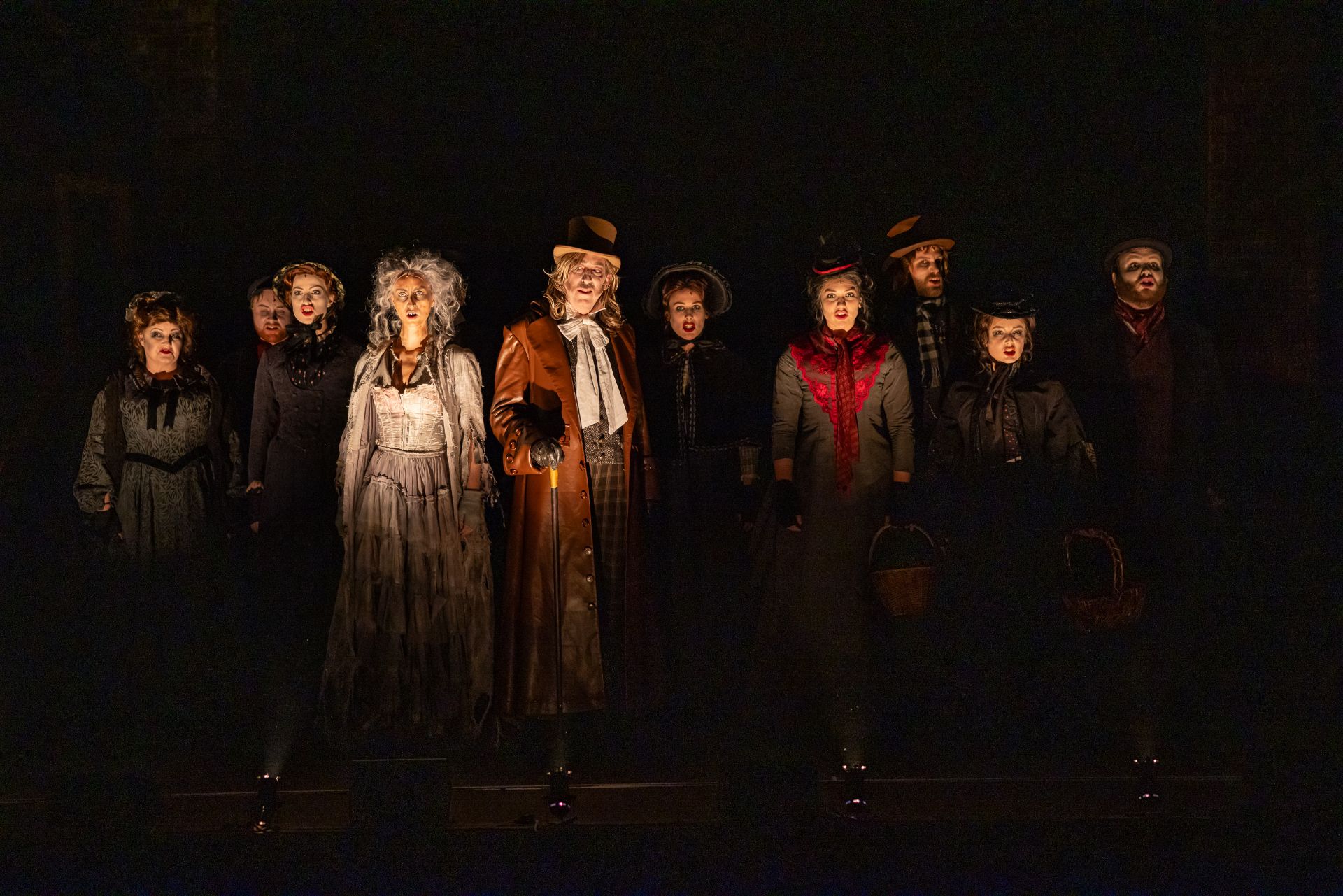

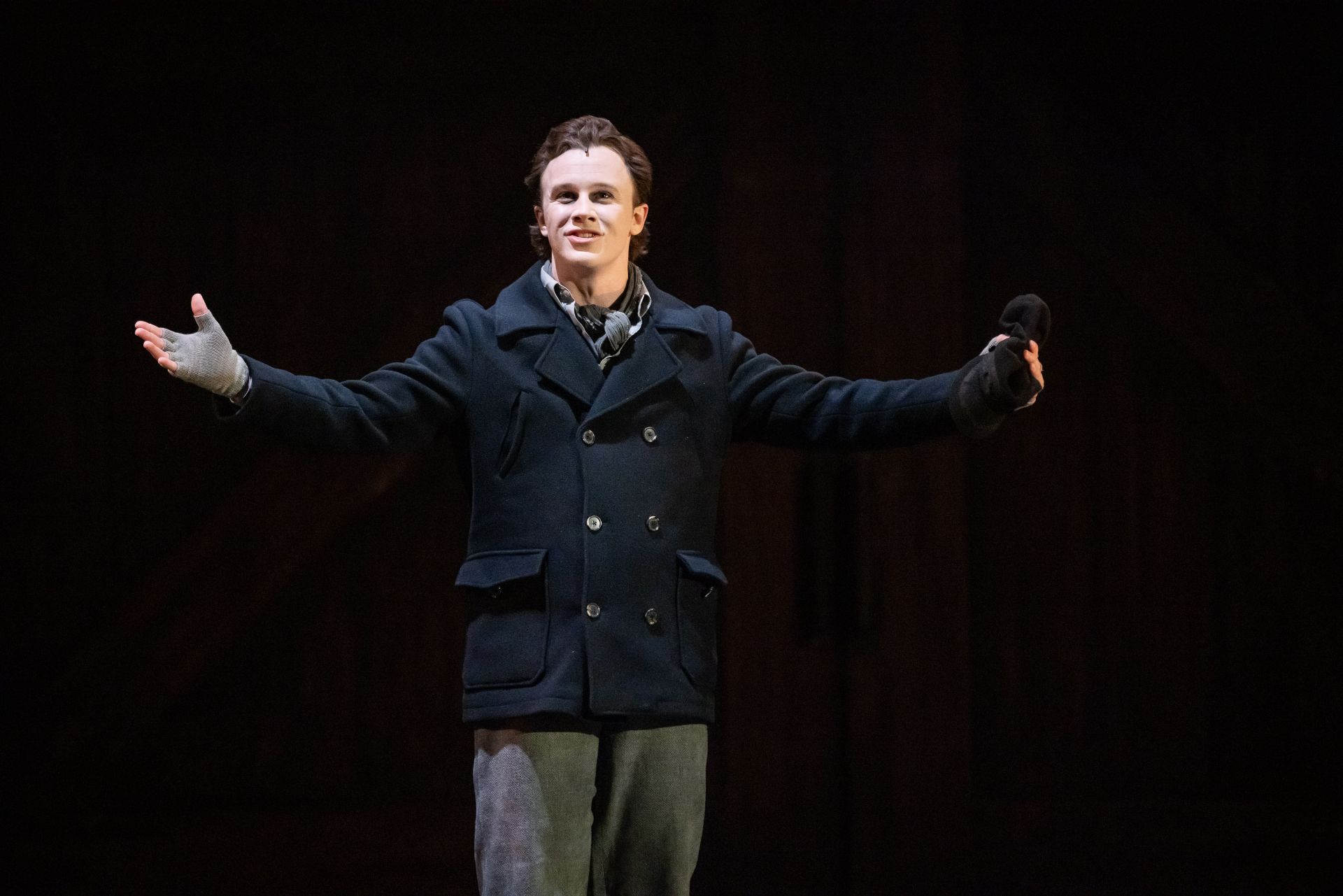

Cast: Roman Delo, Belinda Giblin, Melita Jurisic, Toni Scanlan, Keila Terencio

Images by Brett Boardman

Theatre review

Adele, Jude and Wendy are congregating at their recently deceased friend Sylvie’s beach house, to organise its sale. Charlotte Wood’s novel The Weekend deals with bereavement, through which we explore the meanings of life and of friendship, for women in their twilight years. Sue Smith’s adaptation is a gently humorous stage version, that offers a glimpse into the challenges faced by three fiercely independent and professionally accomplished women, in a world that is not quite built for them.

Directed by Sarah Goodes, The Weekend is occasionally amusing, but with an intense melancholy that reflects a disquieting anxiety associated with the ageing process. Music by Steve Francis provides a sense of longing, one that relates perhaps to the dissatisfaction with a world that routinely neglects older women. Madeleine Picard’s sound design transports us to the idyllic coastal towns of Australia, where we are persuaded to yield to its seductive languor.

Stephen Curtis’ scenic design too, is evocative of that lazy beach life, along with costumes by Ella Butler that depict exactly, the class of people we are looking at. Damien Cooper’s mellow lights tell of the quiet maturity being portrayed. The three leading ladies, Belinda Giblin, Melita Jurisic and Toni Scanlan, offer distinct characters, each one dignified, authentic and intriguing. Puppeteer Keila Terencio brings the enfeebled but charming dog Finn to glorious life, and Roman Delo plays the part of young artist Joe with a charming irony, adding a dose of whimsy to the staging.

Much of The Weekend can feel strangely unaffecting, but there is no mistaking the importance of the discussion. It is true that Adele, Jude and Wendy have each other, but they deserve more. Western culture regards age and death with a grim disdain, that consigns our elderly, especially those of the female gender, to obscurity, leaving them marginalised and abandoned. Unlike the rest of the world, we do not honour the old. We consider our mastery at creating material wealth, to mean a superiority, and refuse to adopt values from other cultures that are plainly virtuous, and beneficial to societies at large. It is a privilege to experience life as an old person, and all our communities should make it a privilege as well, to have the elderly integral to the way we do things.