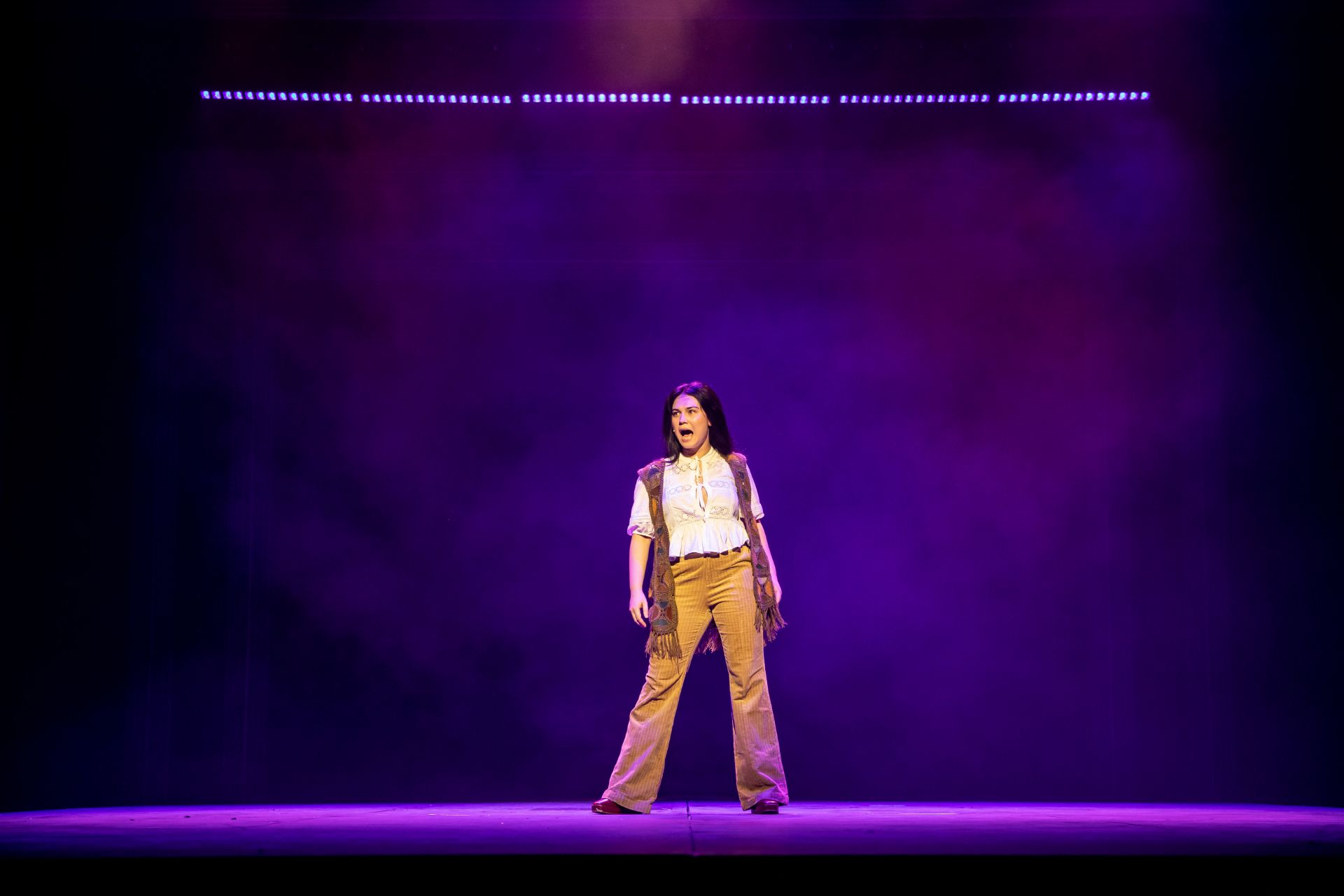

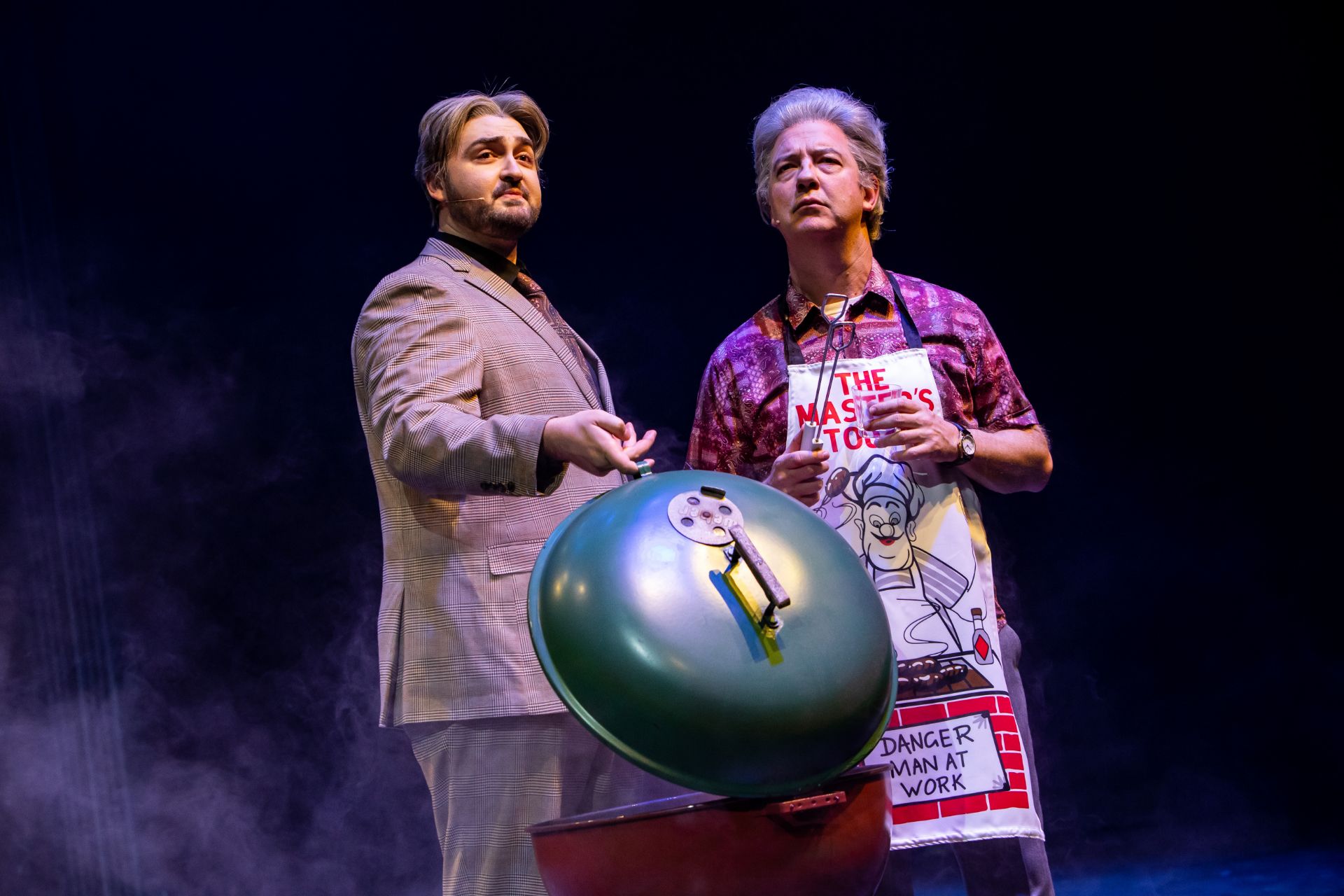

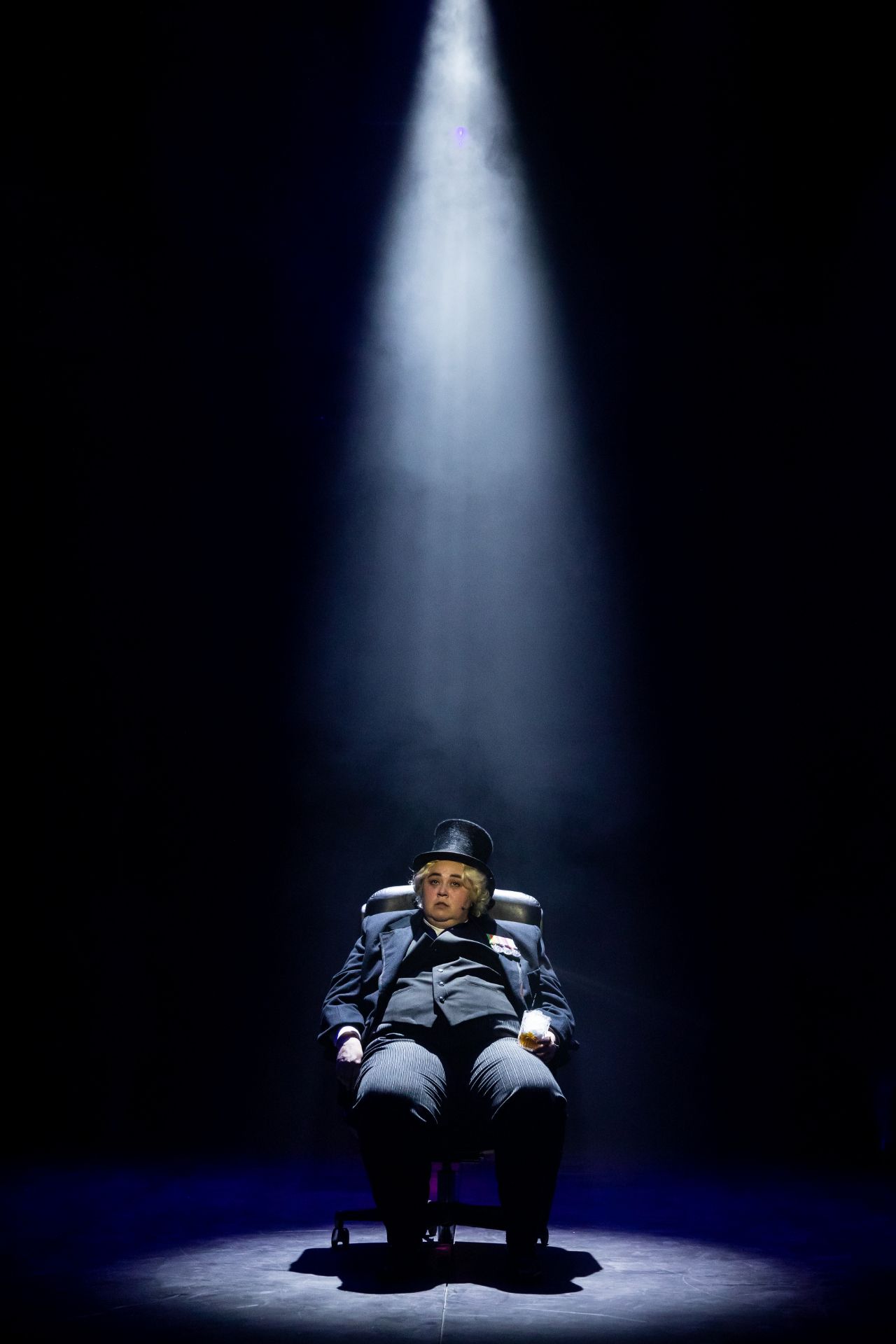

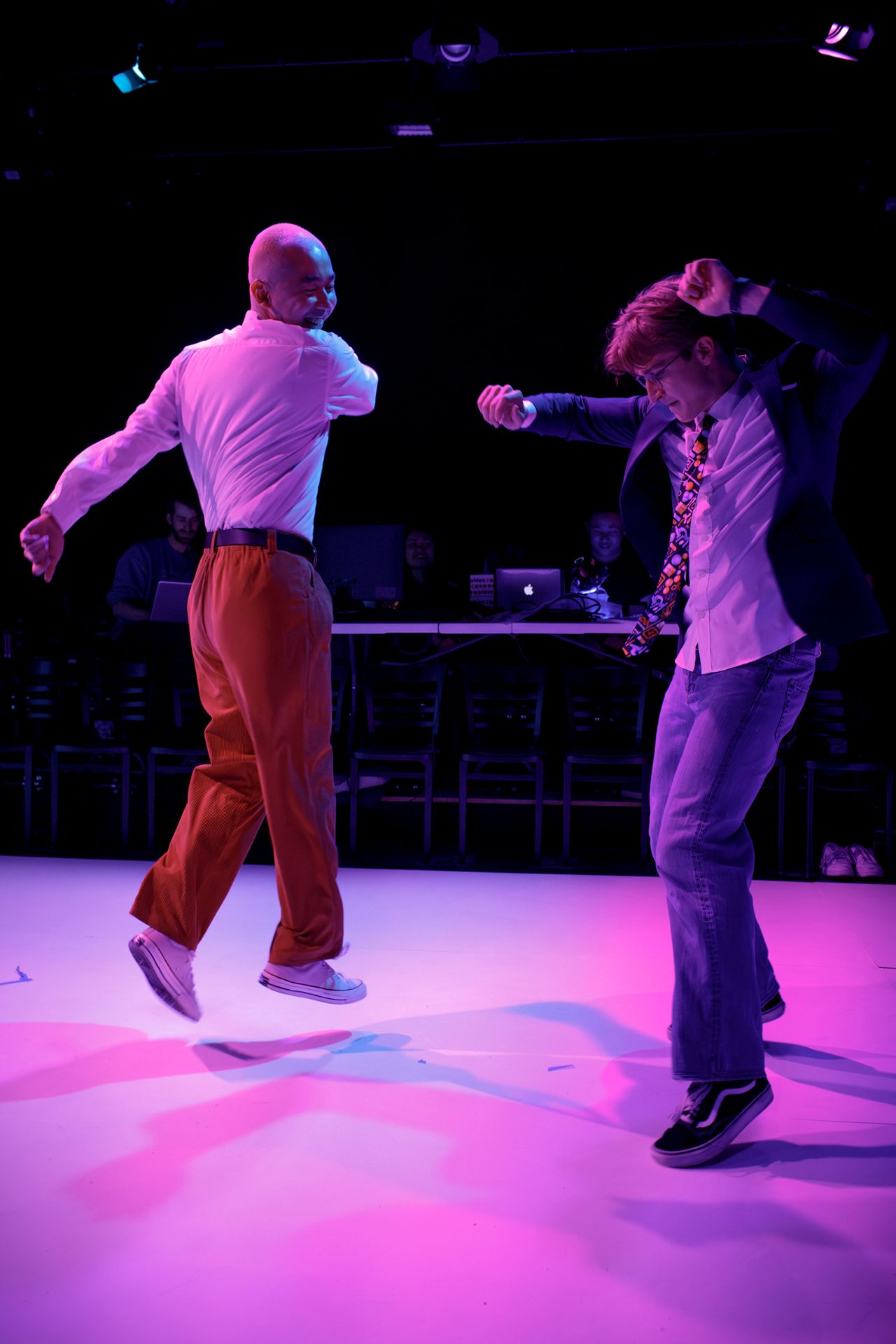

Venue: Ensemble Theatre (Kirribilli NSW), Sep 8 – Oct 14, 2023

Playwright: Hilary Bell

Director: Francesca Savige

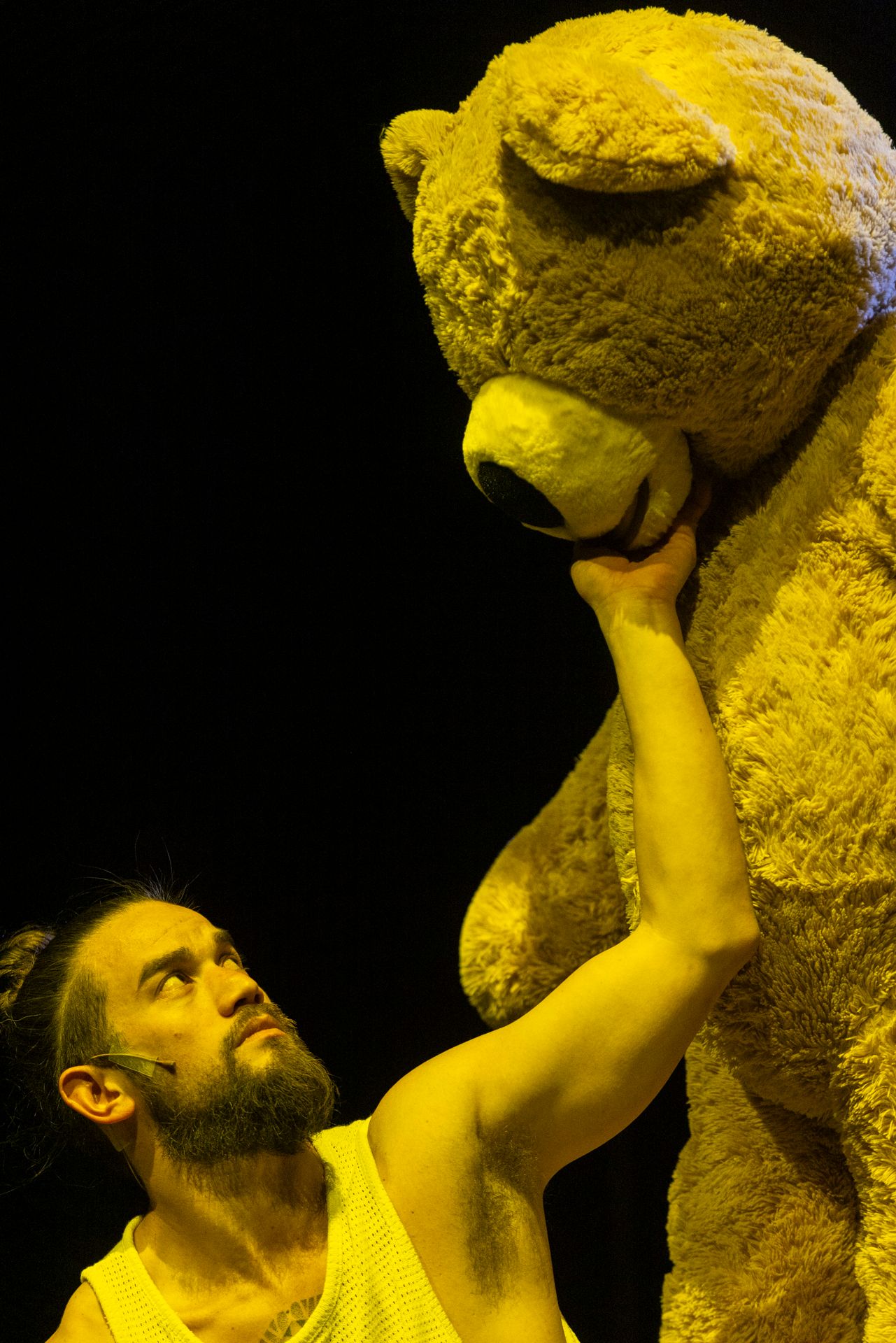

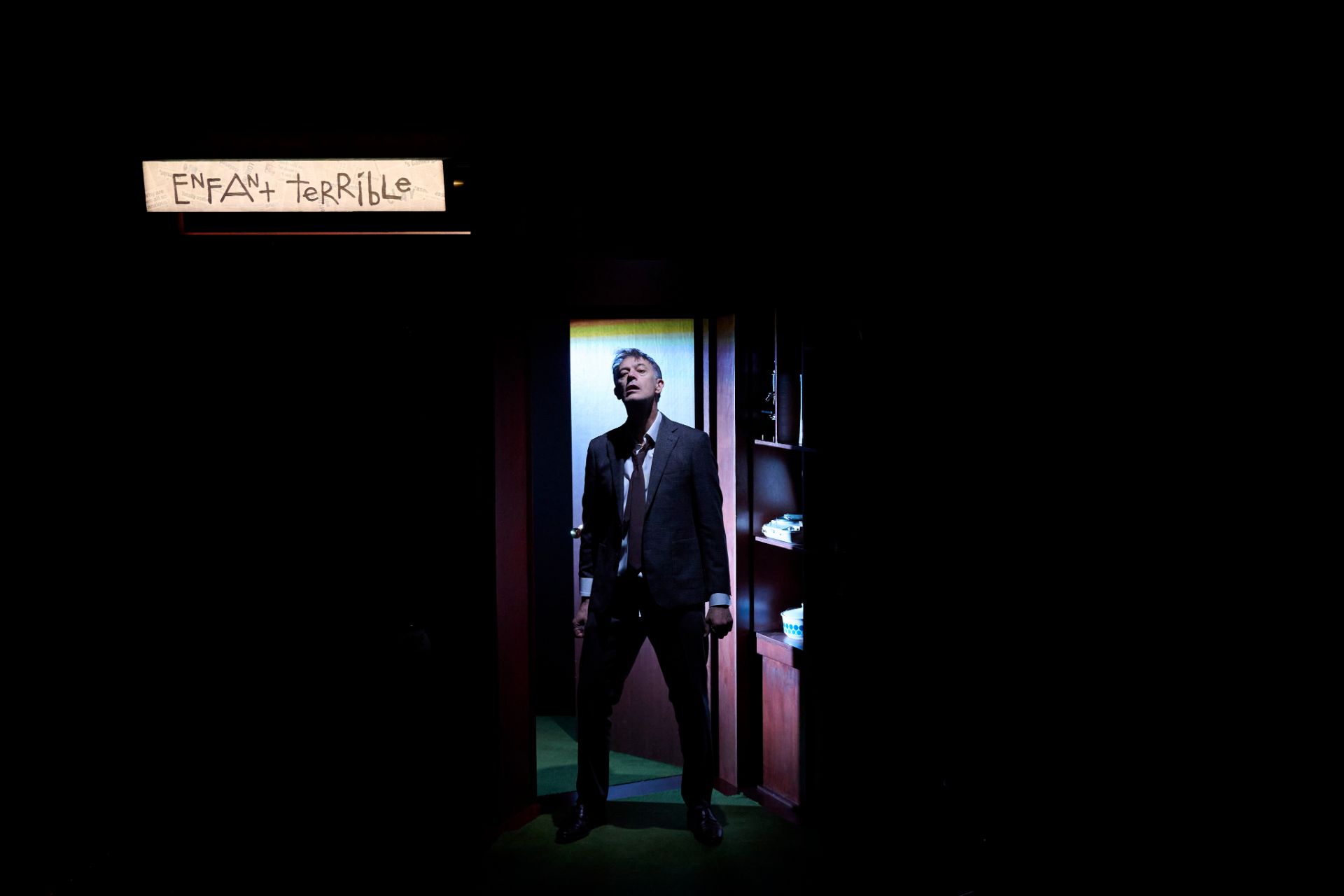

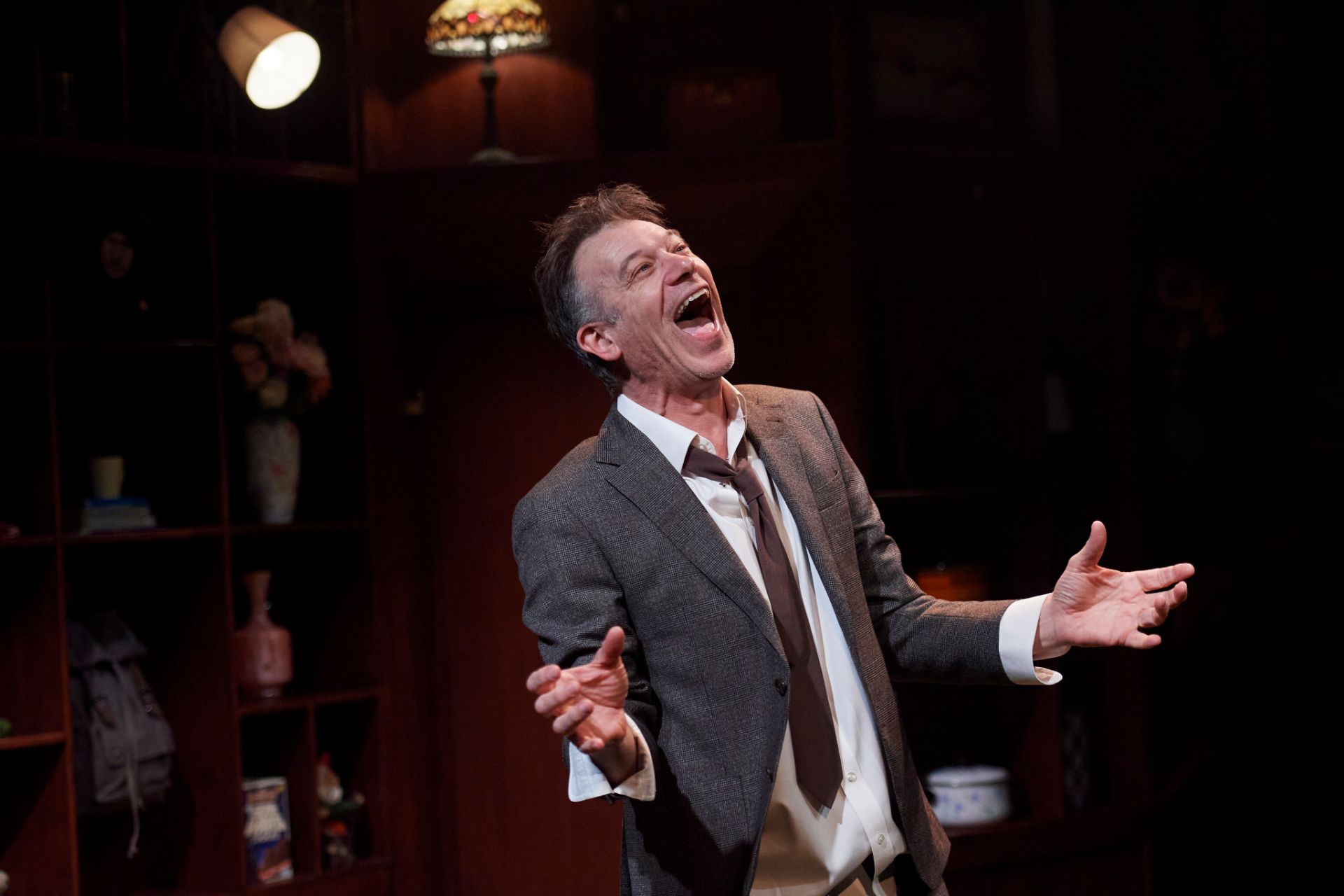

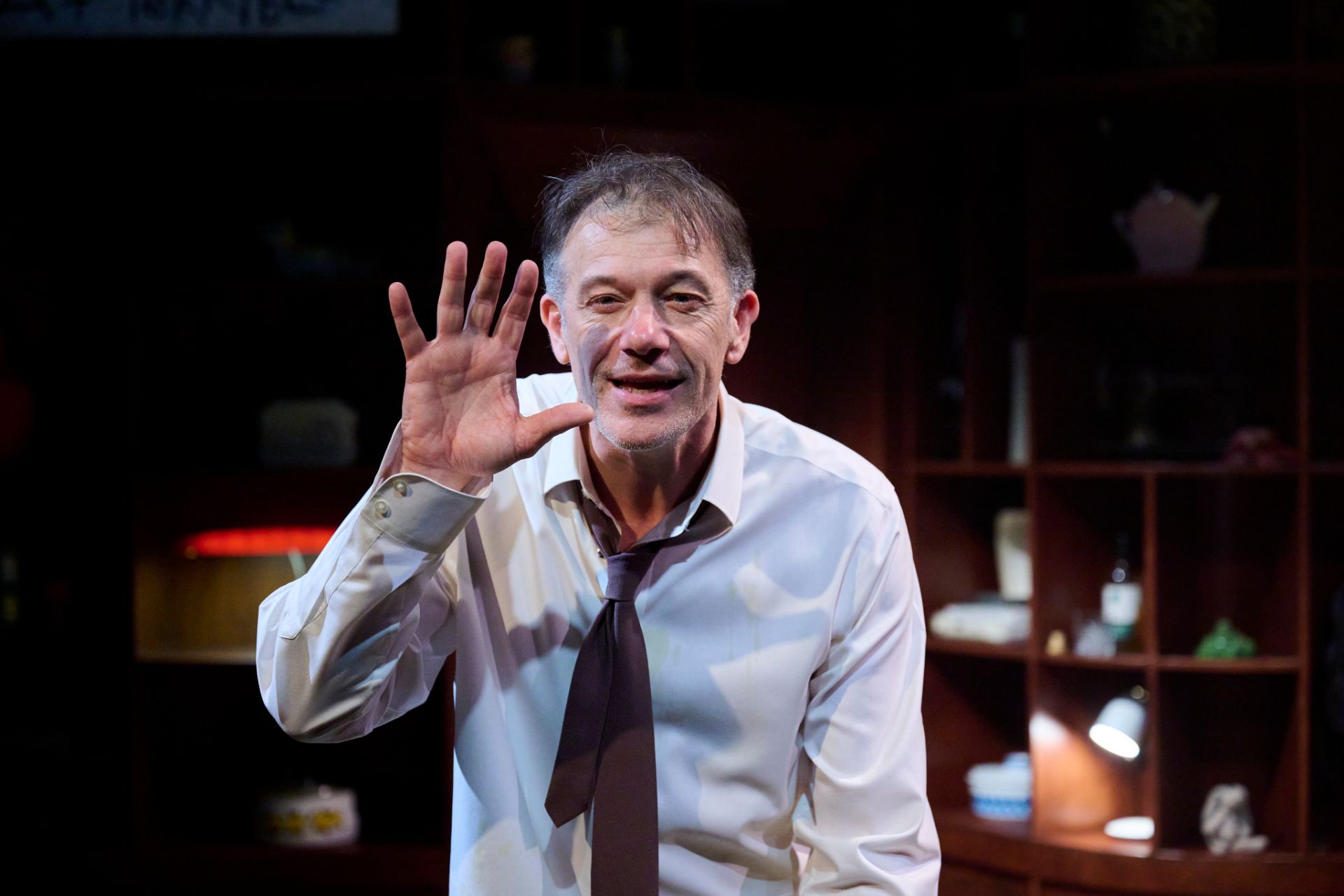

Cast: Berynn Schwerdt, Hannah Waterman

Images by Jaimi Joy

Theatre review

Hilary Bell’s trio of short plays may not be terribly fashionable, with their shared fixation on the 80’s, and a seeming disregard for anything topical that may feel directly relevant, to the myriad trending social concerns competing for bandwidth. It does however pay attention to an older cohort of our population, the ones we have come to nickname “the boomers” who seem to have it all. Yet in Summer of Harold, Enfant Terrible and Lookout, we find these Australian lives to be much more than the privilege with which they are resentfully associated.

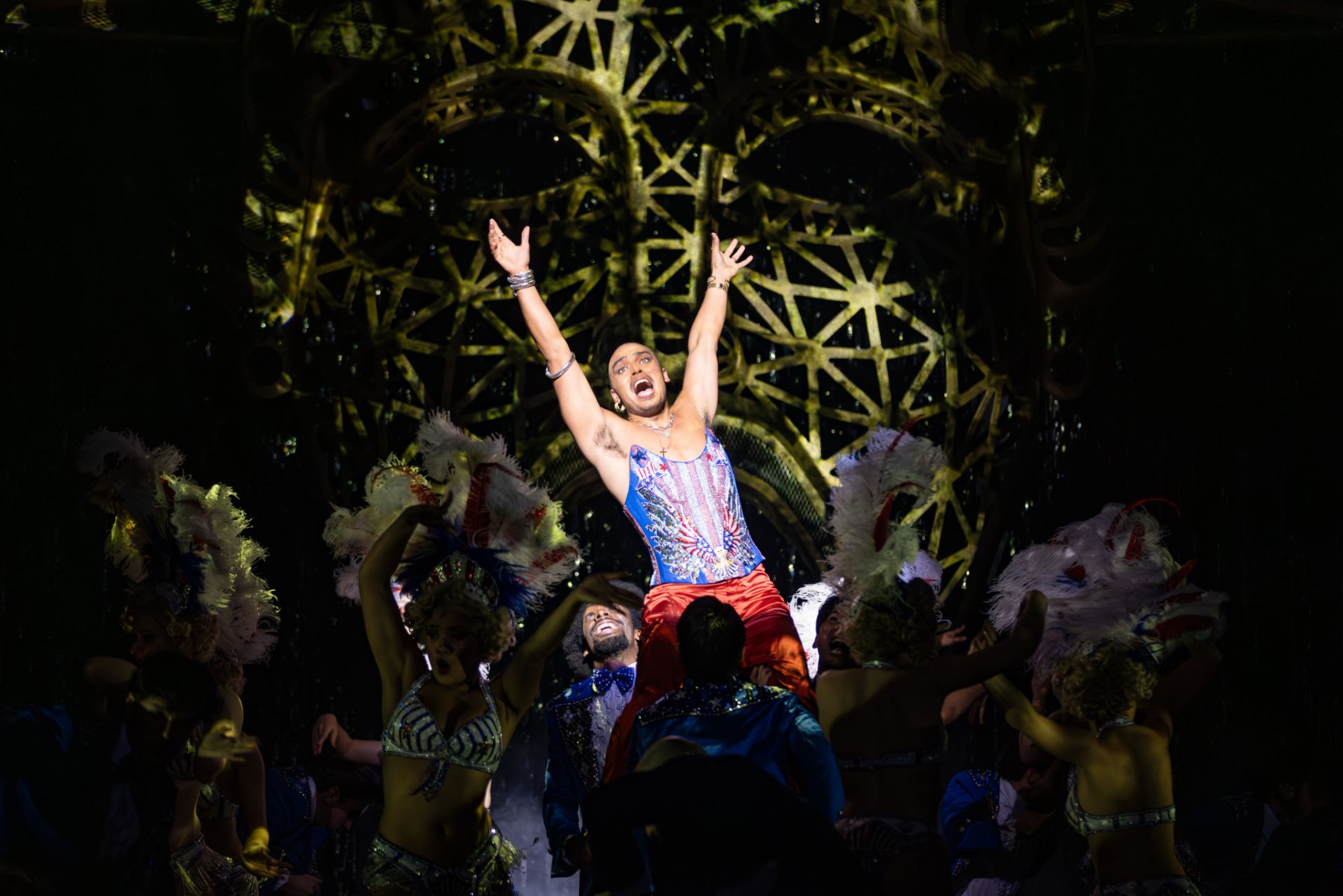

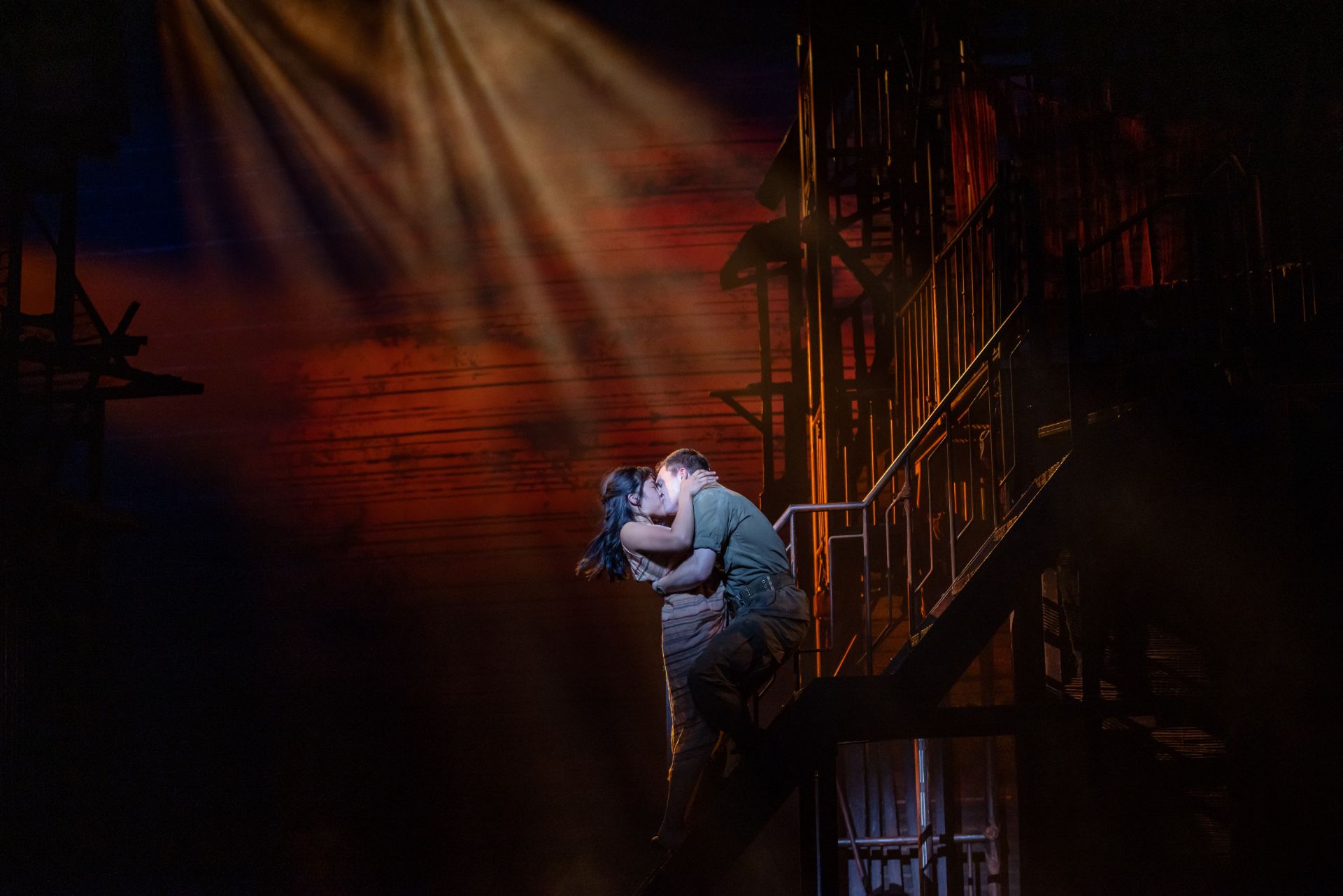

These characters are full of vulnerability, some of them consumed with sadness, others with regret or nostalgia. Bell’s depictions of humanity are certainly truthful, often with a gentle humour that makes her storytelling charming and resonant. Francesca Savige’s tender direction of the pieces is rich with emotion and consistently funny. These explorations are of a particular ordinariness but imbued with an unmistakeable generosity, so that we can perceive the sacred within the mundane, and that something universal can be discovered from these private moments. These stories are small, but Savige ensures that access to their spiritual core is always unrestricted.

It is an attractive stage design by Jeremy Allen that greets us, although not quite versatile enough to accommodate the three completely different settings required of the production. Matt Cox’s lights deliver an elegant sentimentality crucial to our appreciation of these intimate contemplations. Sound design by Mary Rapp guides us effortlessly from one segment to another, leaving a particularly strong impression with the intensity she renders for the final story.

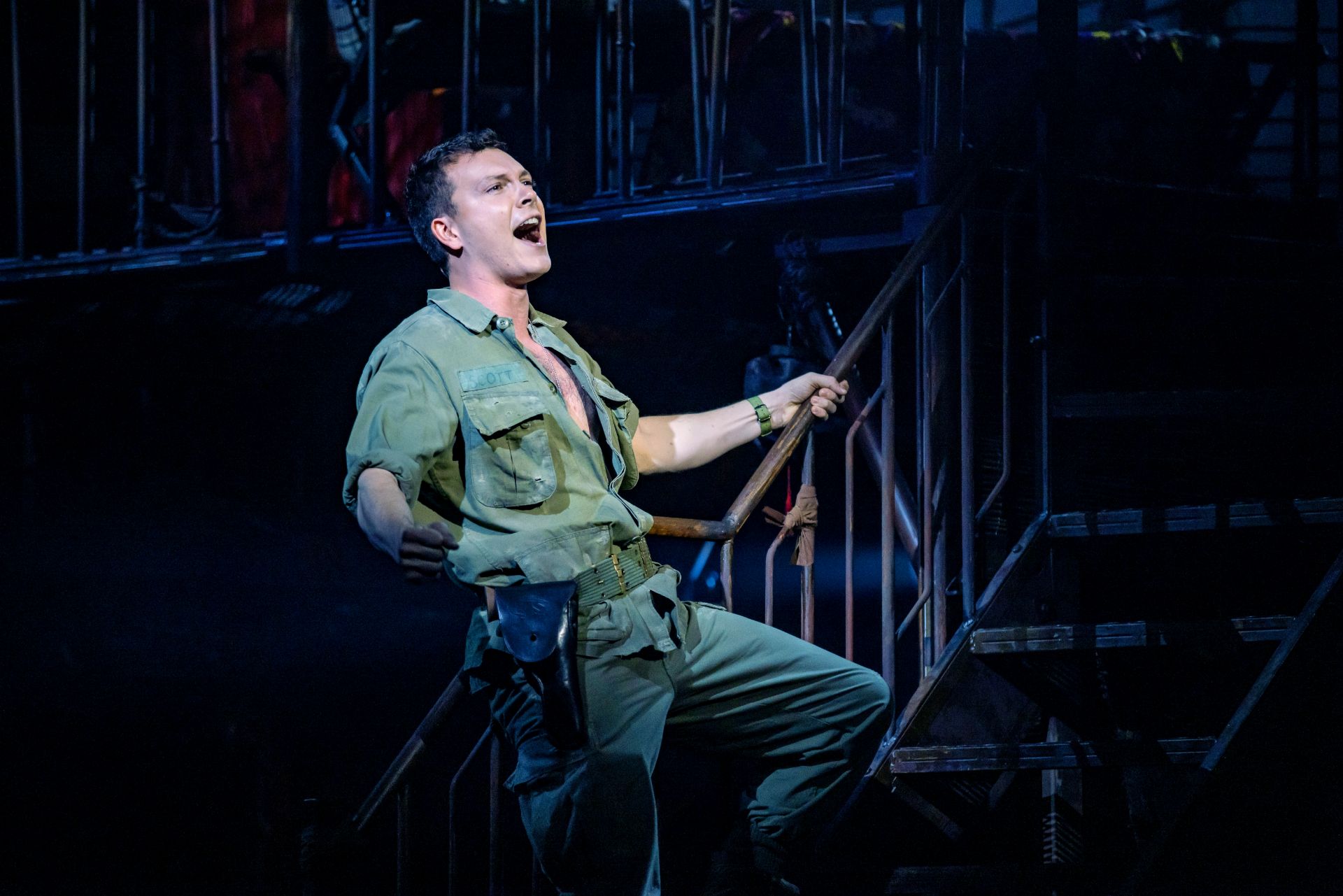

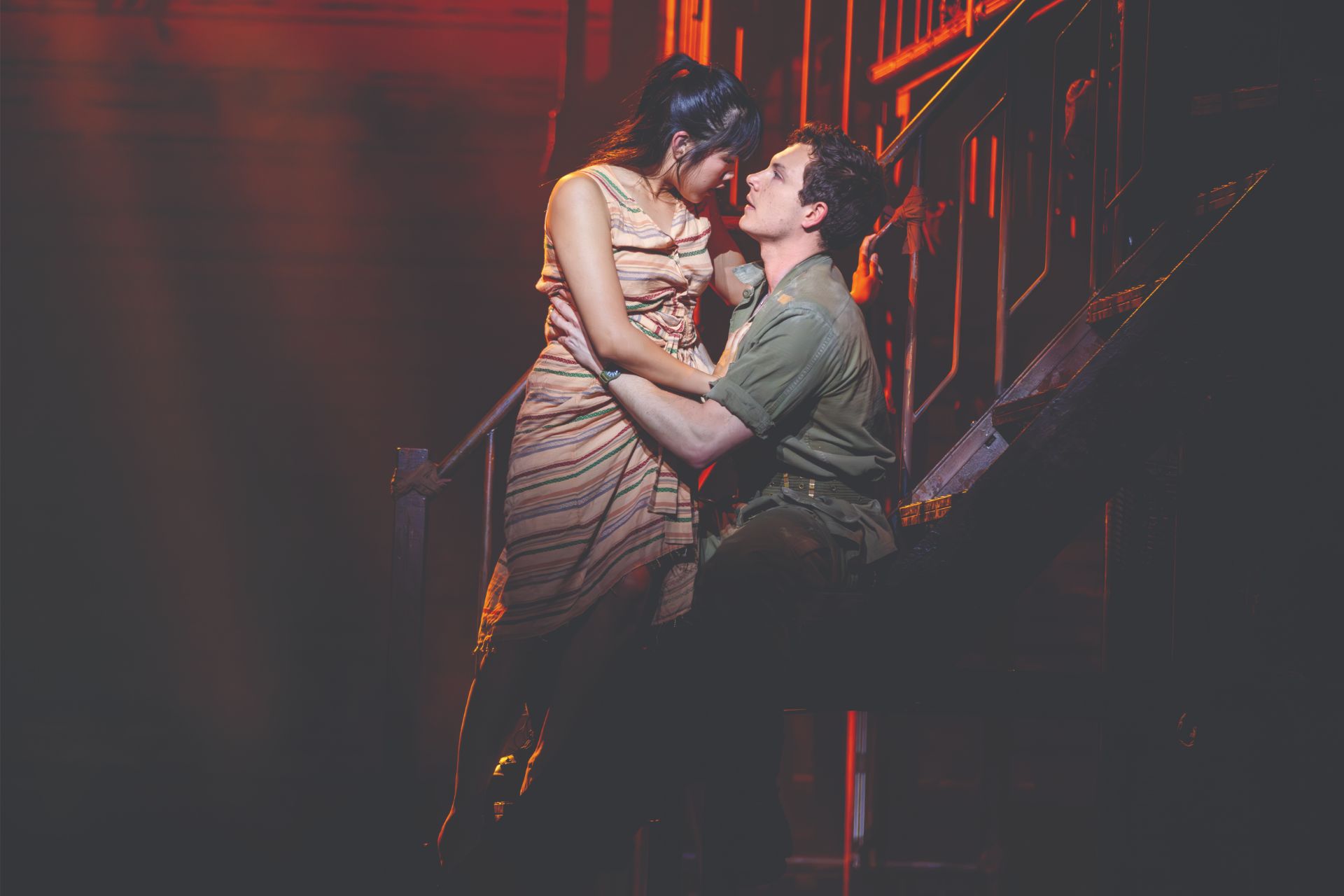

Actor Berynn Schwerdt demonstrates exceptional acuity in his interpretations of Gareth and Jonathan. Highly convincing in completely divergent roles, able to make them equally compelling, with flawless impulses, and an admirable creativity that allows him to introduce surprising nuance at every turn. Playing Janet and Rae is Hannah Waterman, whose rawness as a performer invites us to connect with the internal dimensions of the women being portrayed, both of whom seem so cordially familiar.

Some of these characters we meet, have pasts they need to leave behind, while some others are quite content staying put. Time can be thought of as linear, especially useful when indulging in flights of fancy pertaining to matters of progression. History does show undeniable propensity in how we are able to make things better. Time can also be thought of as circular or oscillatory, so that we may feel no inadequacy in this state of being, that one is always enough wherever one might be. Fortunately both are concurrently, and eternally, real.