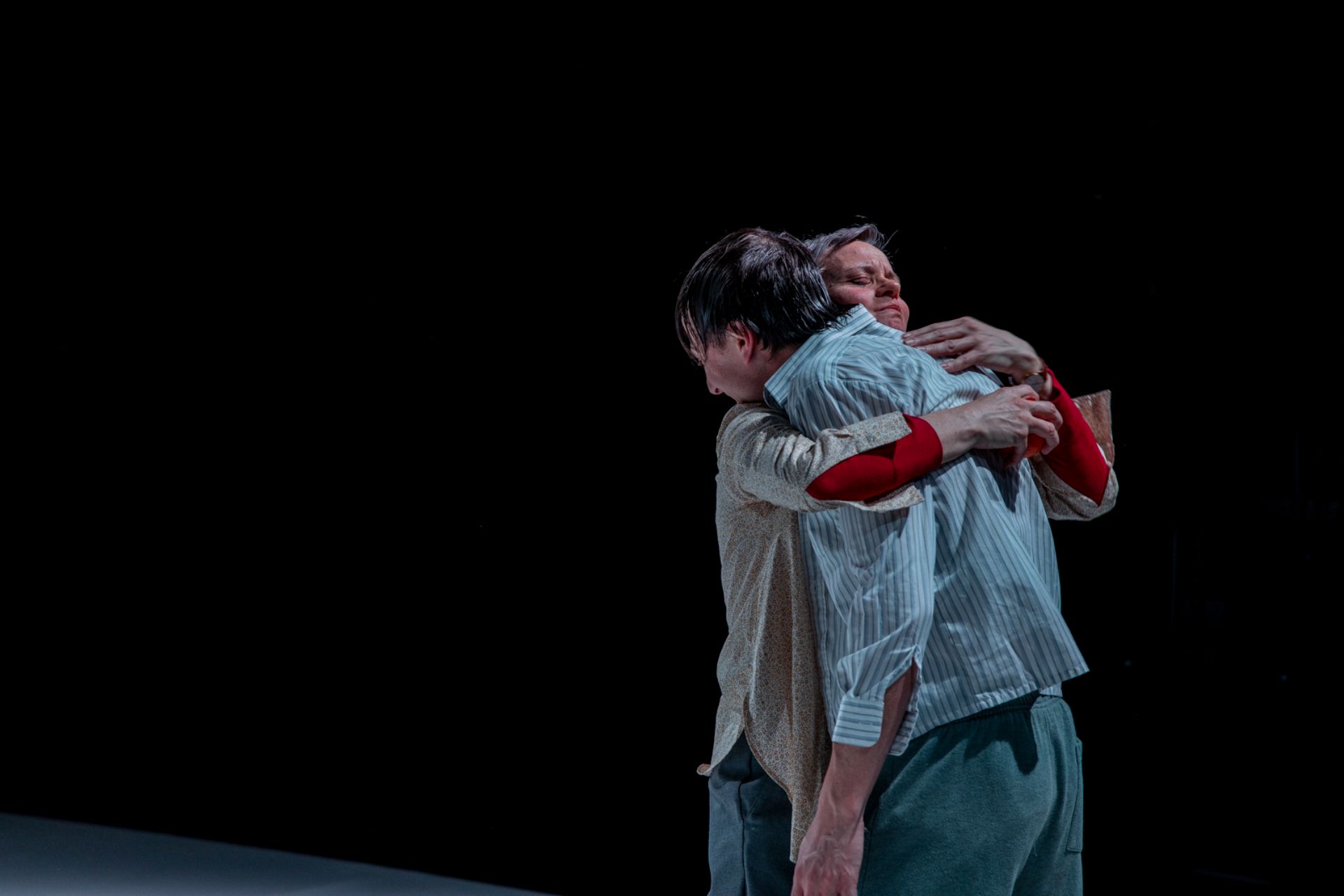

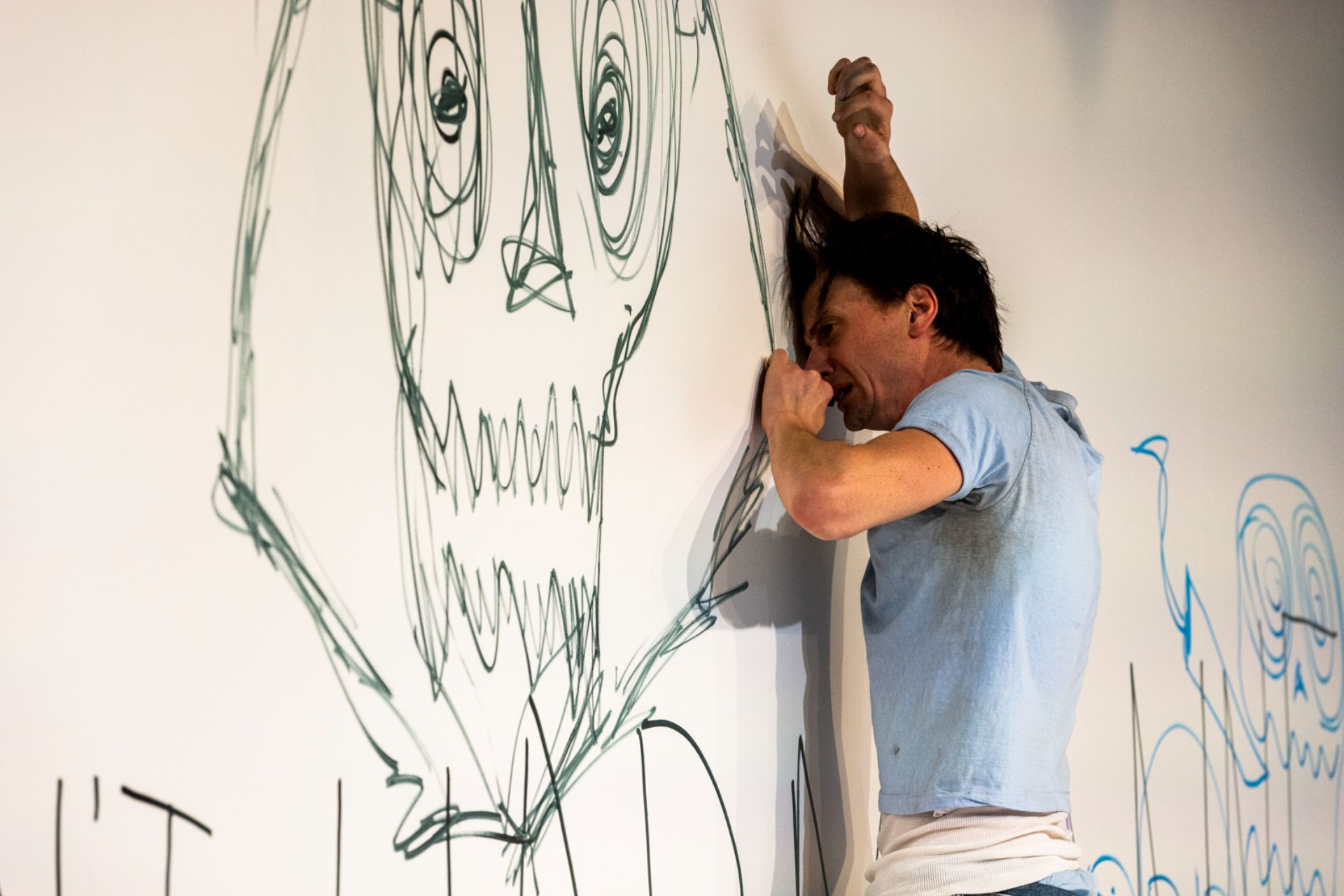

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Sep 15 – Oct 29, 2022

Playwright: Angela Betzien

Director: Jessica Arthur

Cast: Ezra Juanta, Catherine McClements, Michelle Ny, Nathan O’Keefe, Susan Prior, Stephanie Somerville

Images by Prudence Upton

Theatre review

Pat has been teaching for far too long, at West Vale Primary, a government school severely deprived of resources. Everything seems to be falling apart, not least of all its teaching staff. Pat’s palpable cynicism stands in stark contrast, against newcomer Anna, who turns up first day of term, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, to join the decidedly jaded team. In Angela Betzien’s Chalkface, we look at the public education system, and the people who do all the heavy lifting to keep it running.

Betzien’s keen observations are presented with cutting humour, for a work that delivers many laughs, based on our own refusal to do better for so many teachers and children. It is satisfying satire that inspires debates on our values, especially as they relate to resource allocation, thereby interrogating our priorities as a nation. Direction by Jessica Arthur leans on the writing’s acerbic qualities, for a production that appeals with its gentle irreverence. The comedy manifests in a style of theatricality that is unquestionably bold and mischievous, but the show is ultimately, and unsurprisingly, highly respectful of the teaching profession.

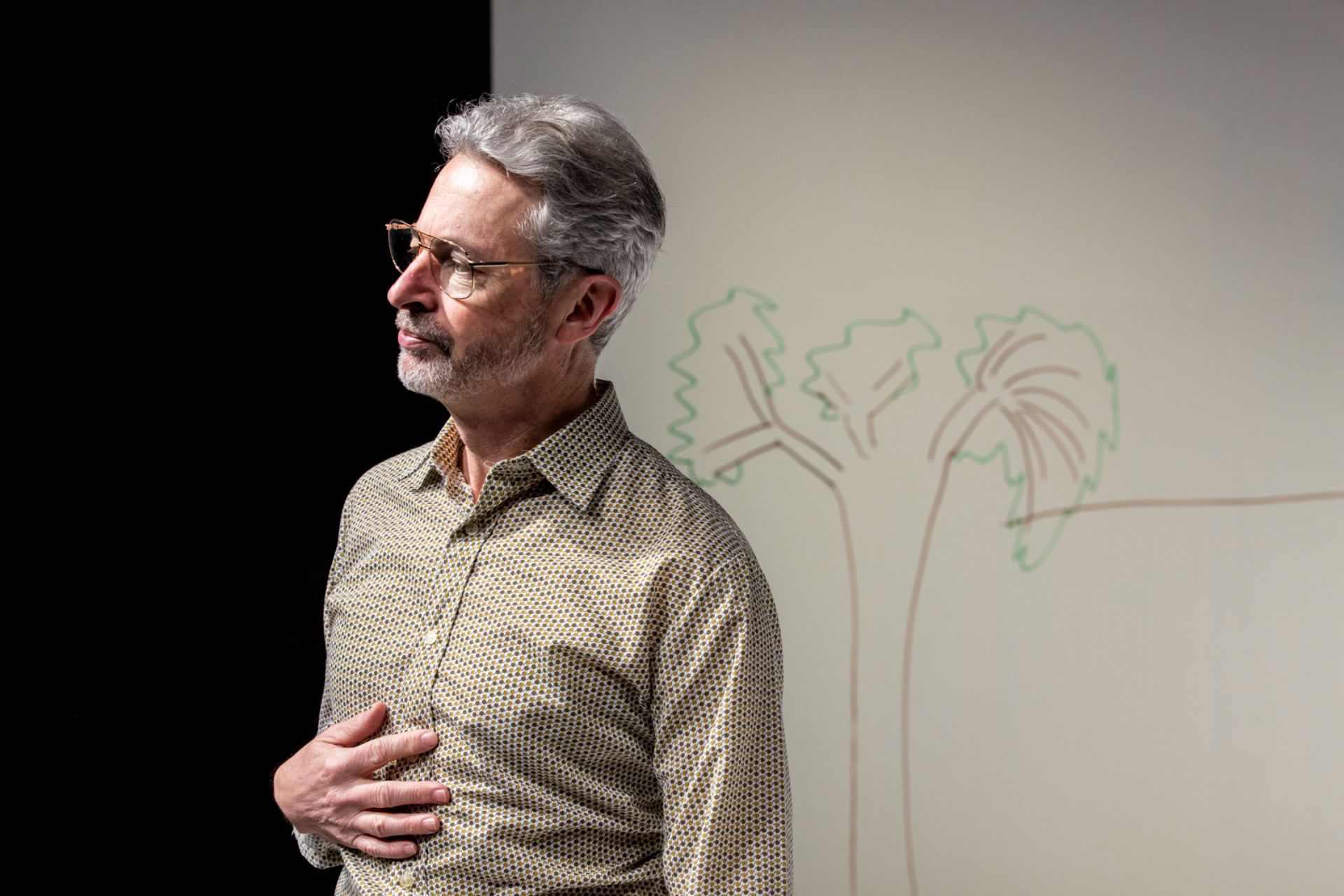

Chalkface features six characters, all of whom are made endearing by Arthur’s thoughtful approach to the depiction of humanity, in the midst of a lot of amusing hullabaloo. Actor Catherine McClements is wonderfully entertaining as the astringent Pat, turning middle-aged grumpiness into something altogether more playful and charming. Her portrayal of the burnt out civil servant drives home a salient point, about our failure to take care of those, who do some of our most important and hard work. Stephanie Somerville does an admirable job, of preventing the idealistic young woman from ever becoming nauseating, with an understated sassiness and confidence, that makes Anna a persuasive presence.

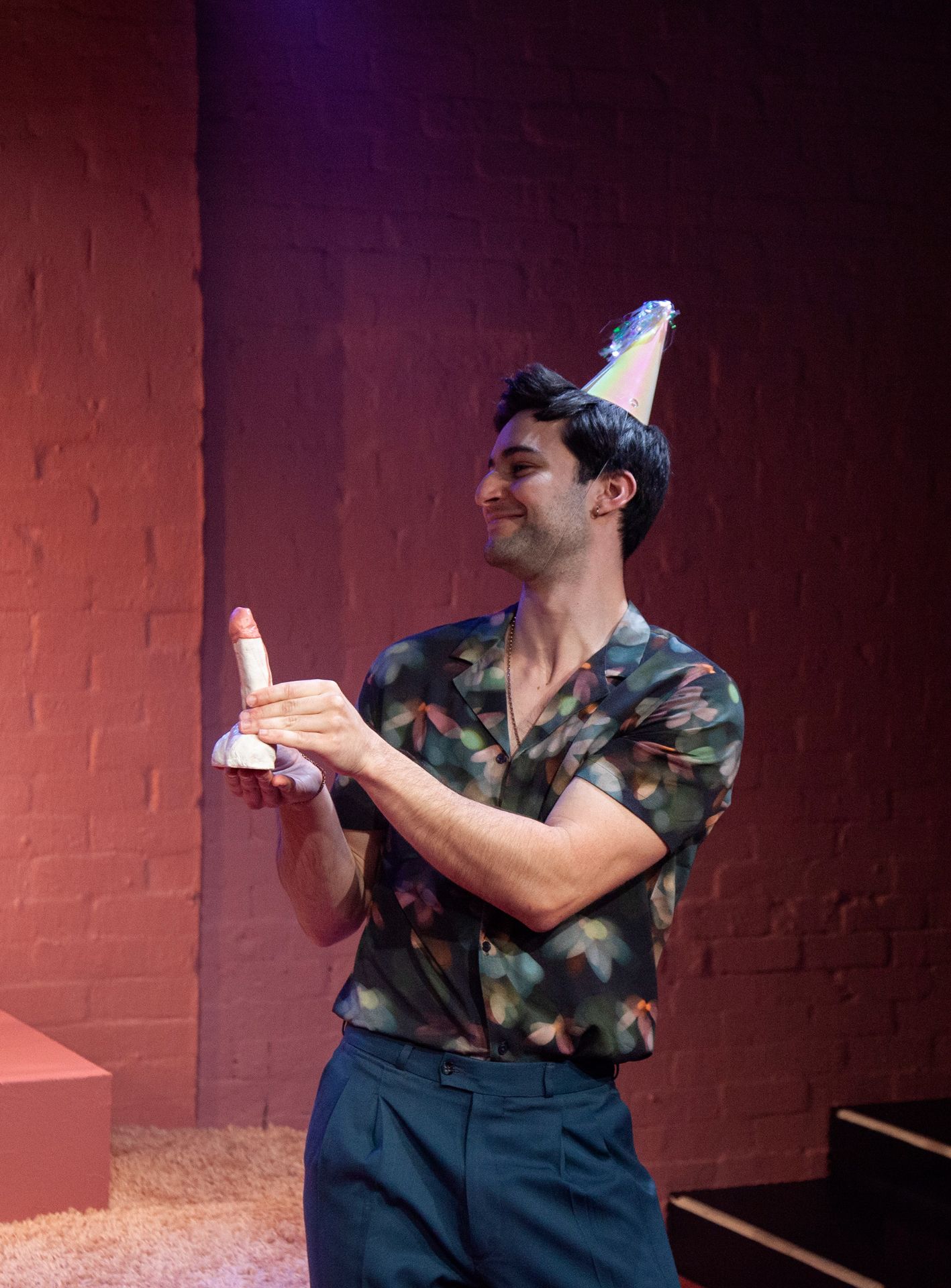

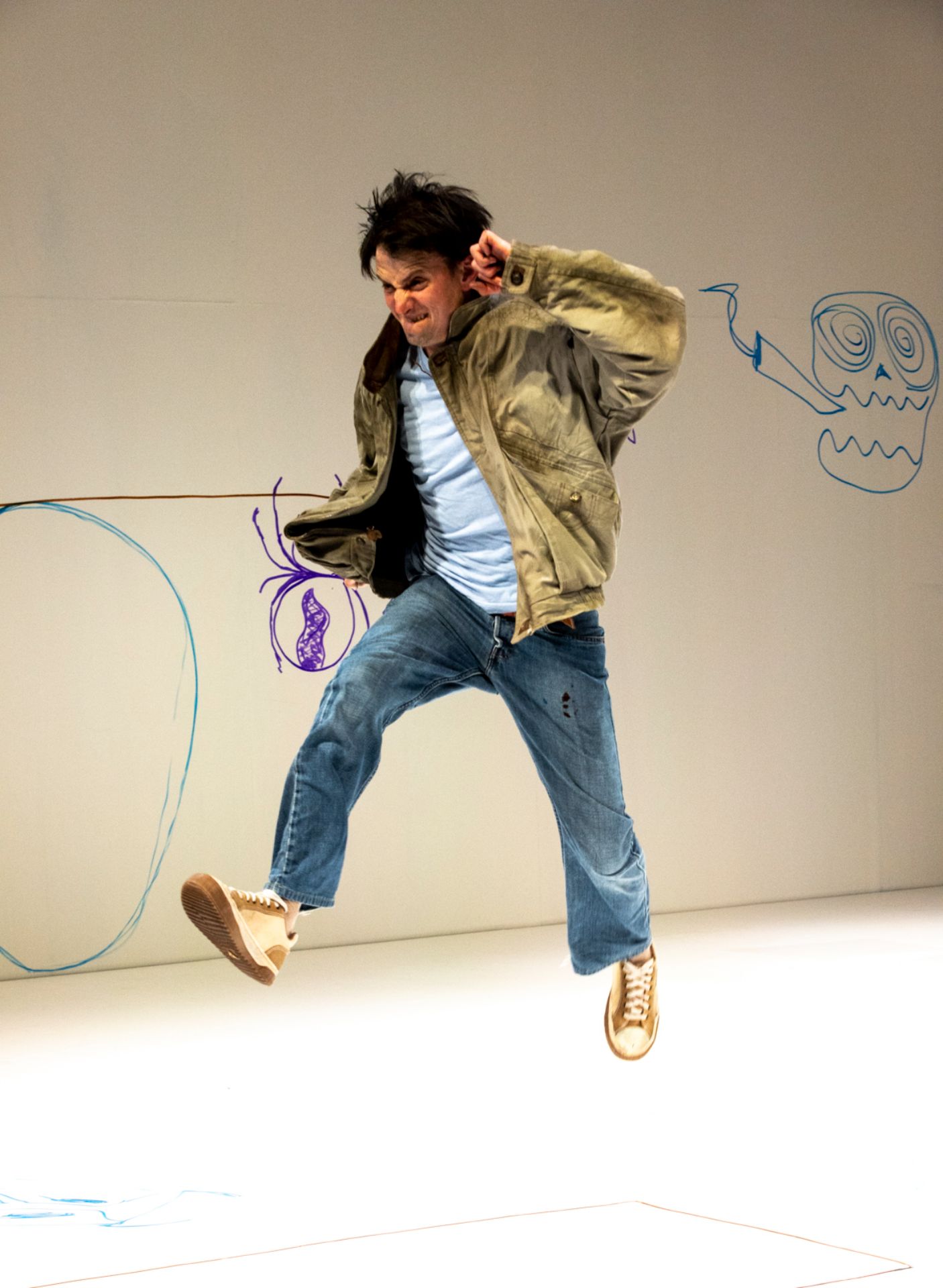

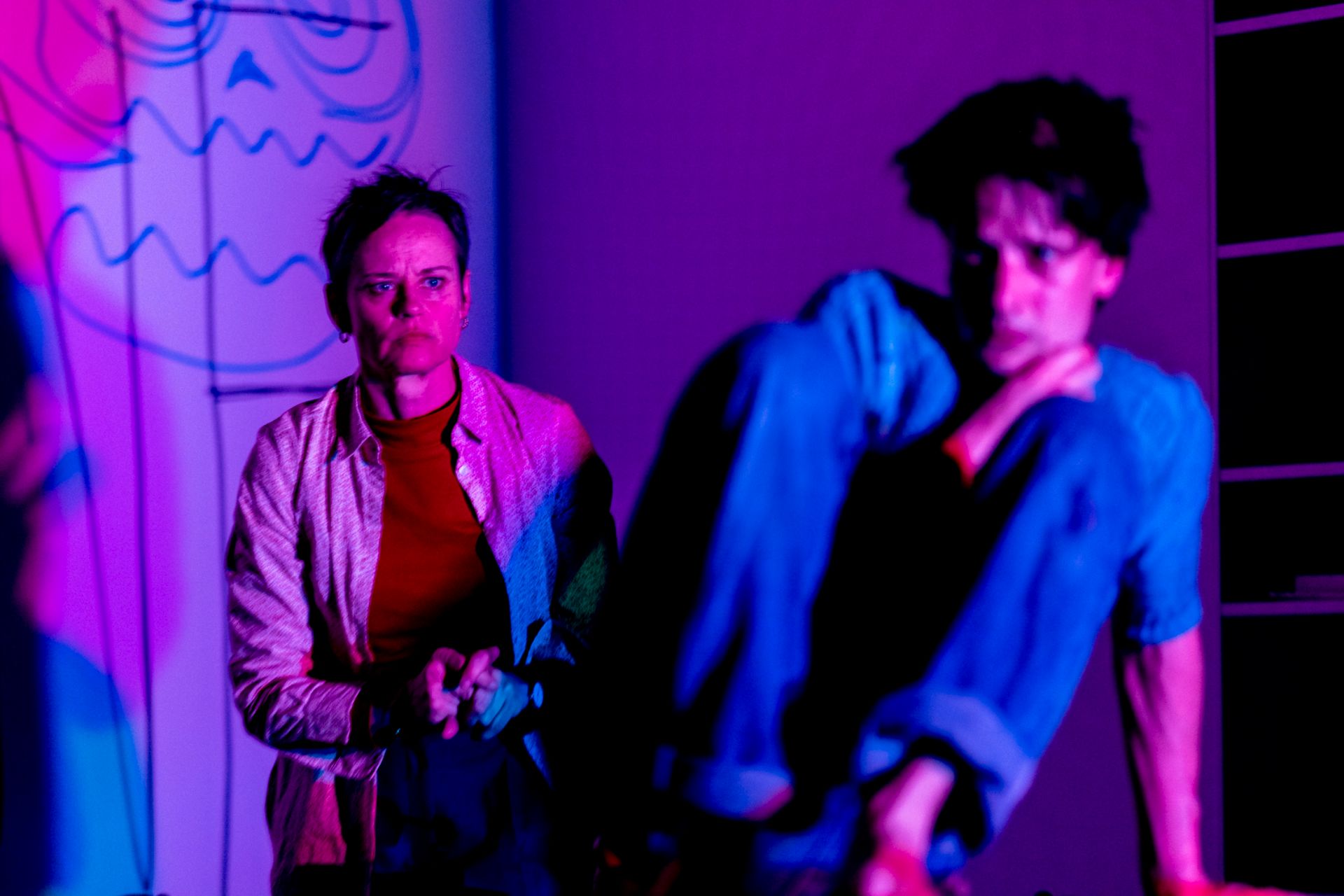

Ezra Juanta and Susan Prior deliver a couple of madcap performances, as Steve and Denise respectively, both with exaggerated eccentricities that enrichen and enliven the storytelling. Similarly outlandish are Michelle Ny and Nathan O’Keefe, who play the slightly villainous members of administrative staff Cheryl and Douglas, bringing unyielding flamboyancy to a relentlessly exuberant presentation.

Ailsa Paterson’s set and costume designs offer appropriately comedic renderings of that scrappy world, with an unmistakable sense of disintegration, for the staff room and for the people who occupy it. Lights by Mark Shelton, and music by Jessica Dunn are utilised most vivaciously between scene changes, taking the opportunity to further uplift our spirits.

It goes without saying, that we should always strive to do better for our children. It is incredible however, to witness the extent to which some are willing to sacrifice, in the belief of doing what is right for future generations. There is nothing at all controversial, in saying that our teachers are the bedrock of society, but to suggest that those who contribute the most within our education system, should receive commensurate remuneration, seems to be eternally contentious.