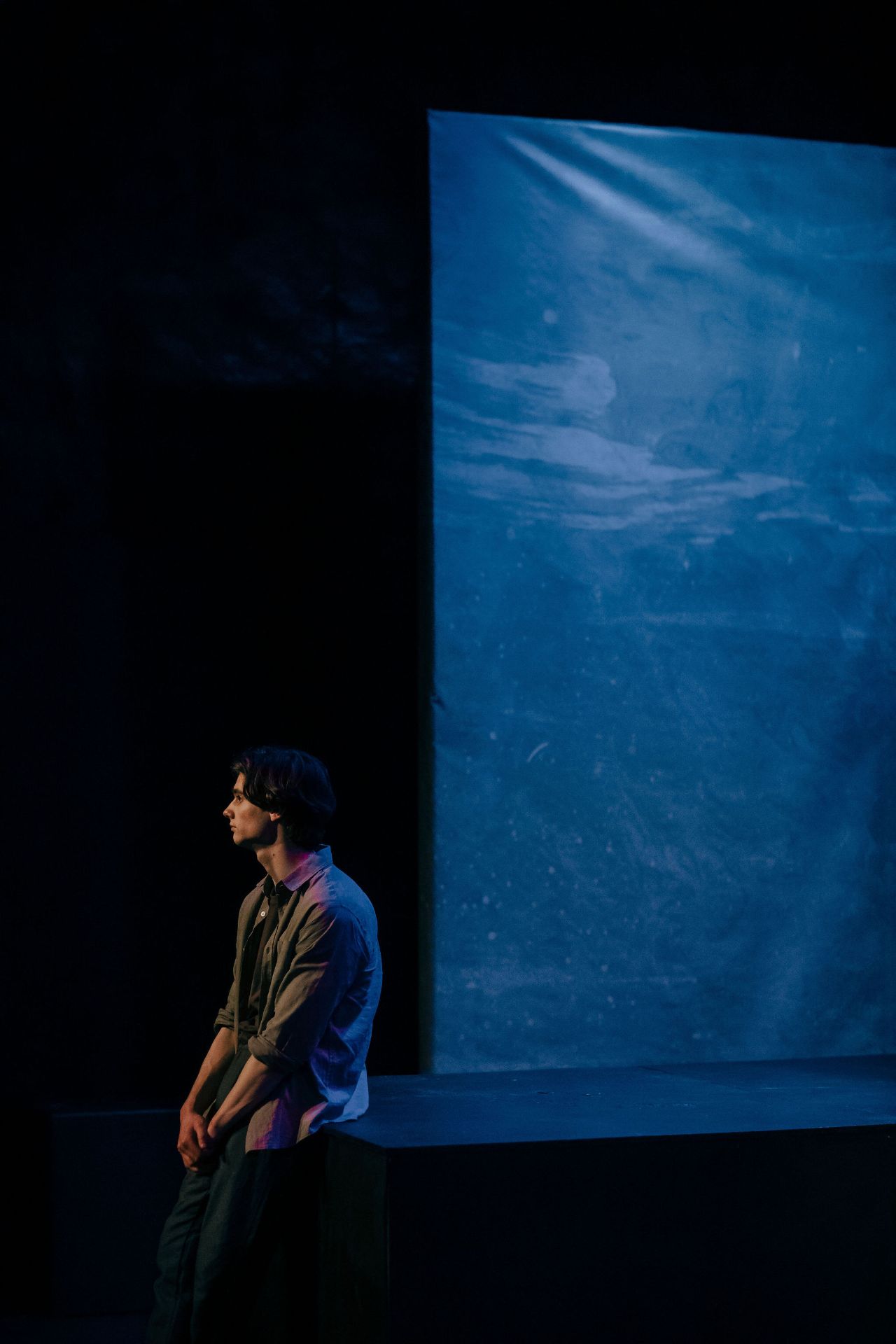

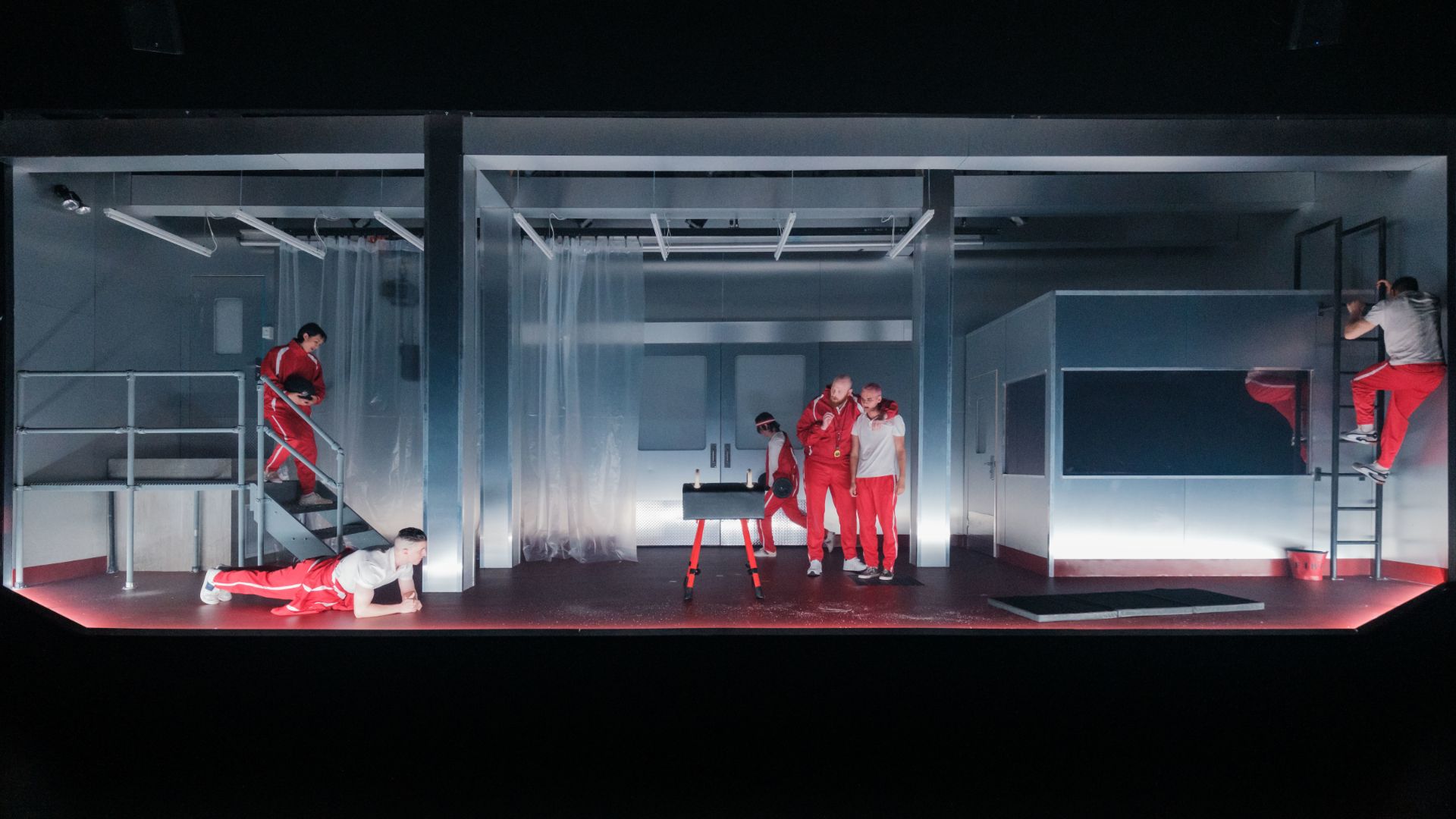

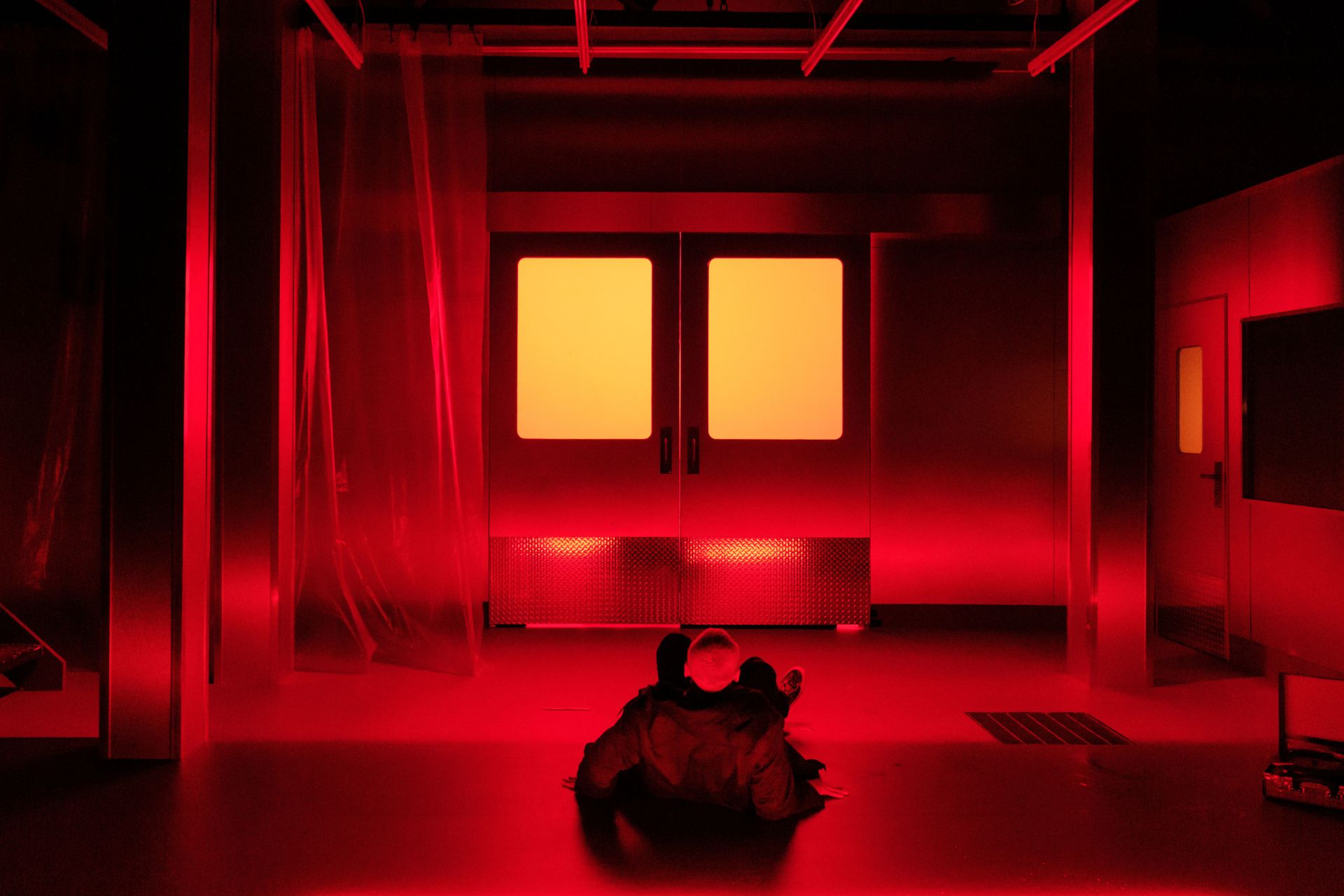

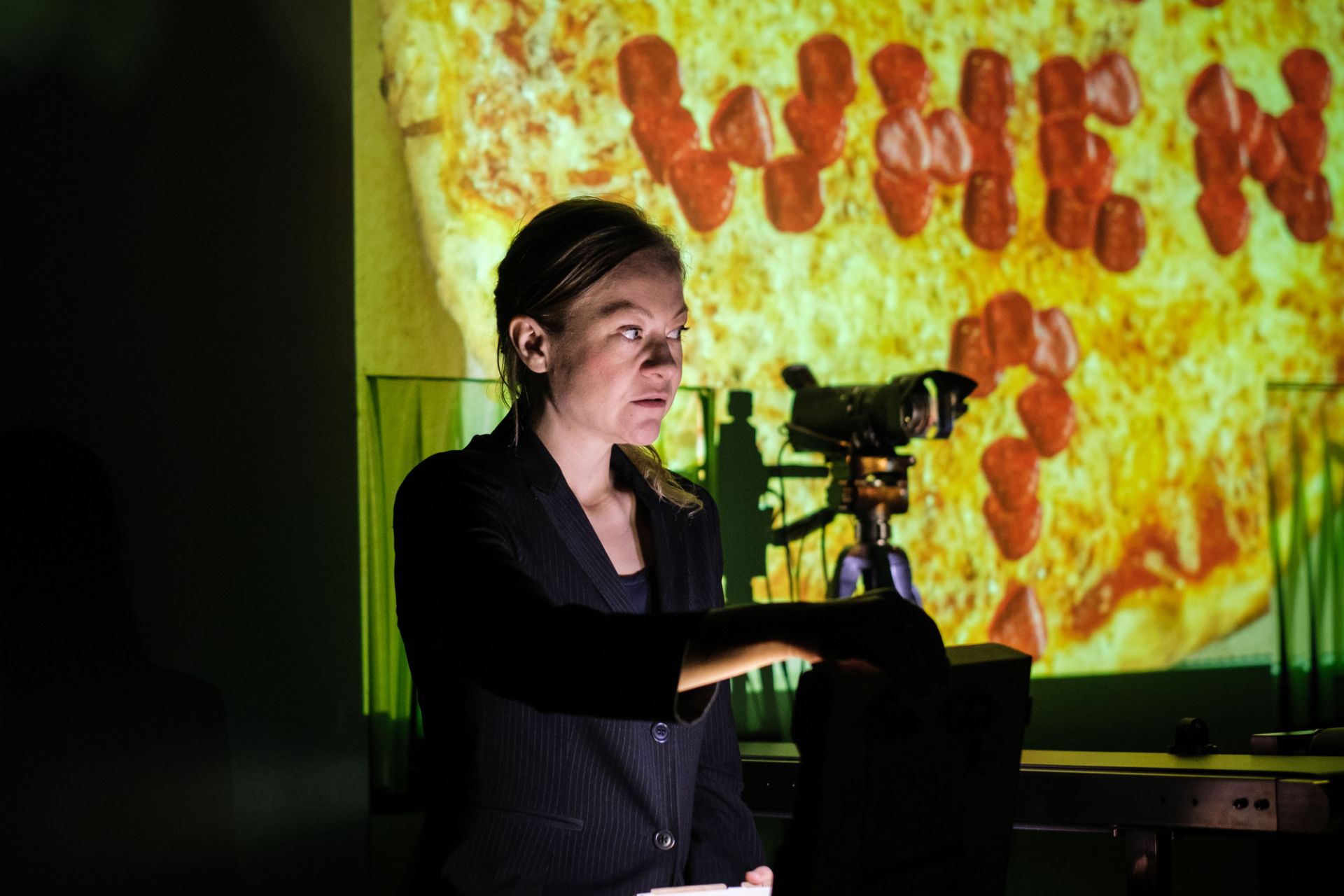

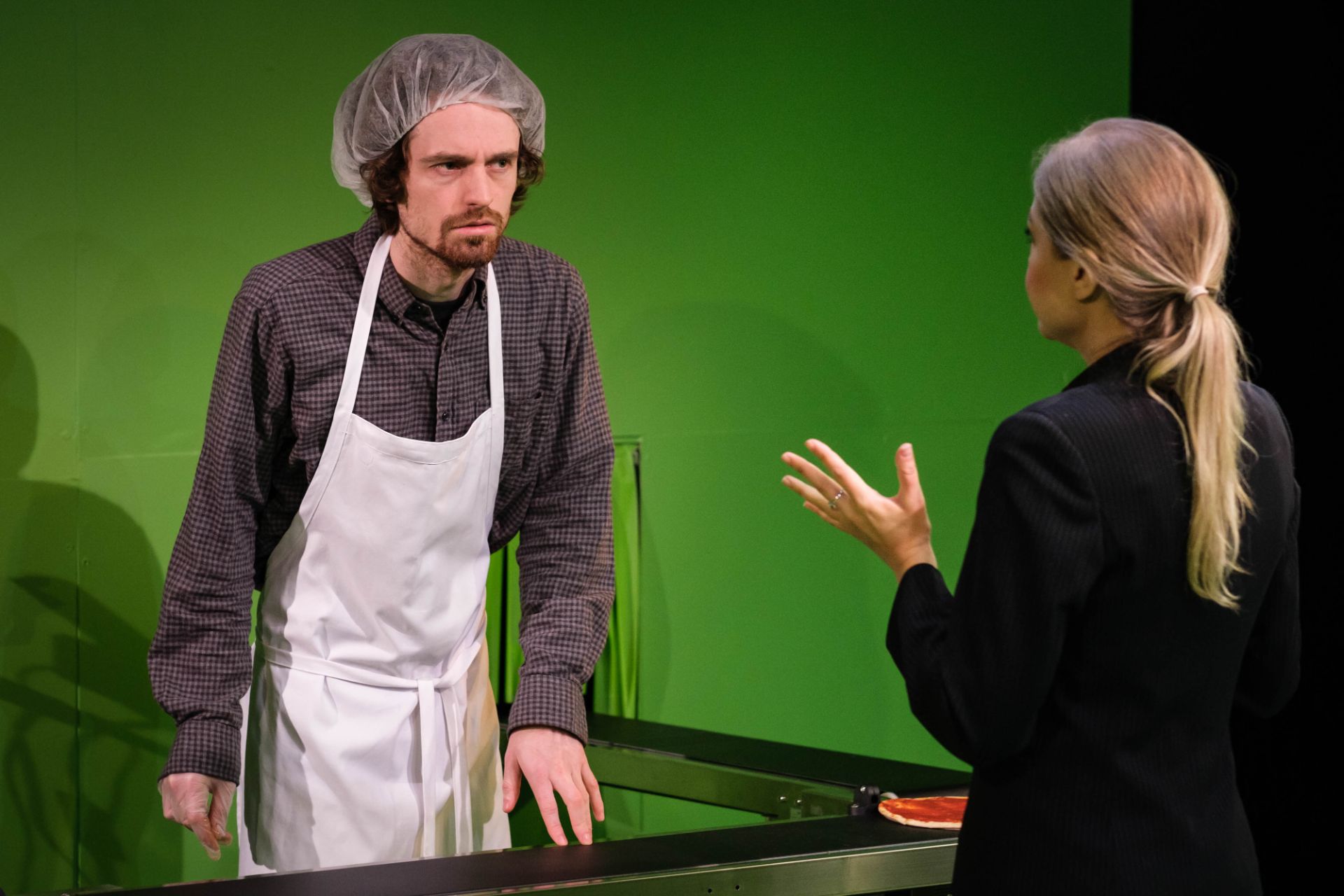

Venue: SBW Stables Theatre (Darlinghurst NSW), Oct 13 – Nov 5, 2022

Playwright: Ash Flanders

Director: Stephen Nicolazzo

Cast: Ash Flanders

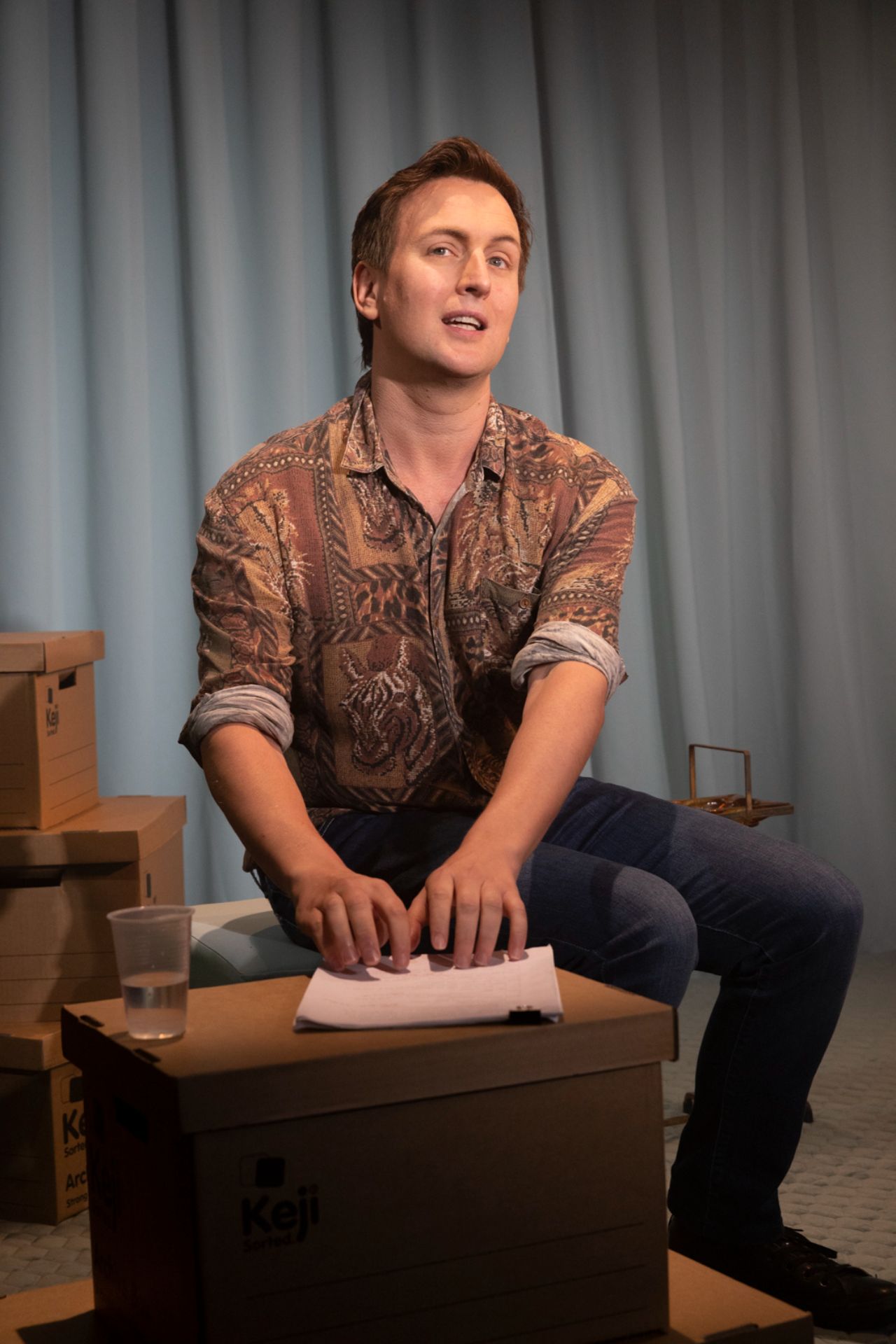

Images by Brett Boardman

Theatre review

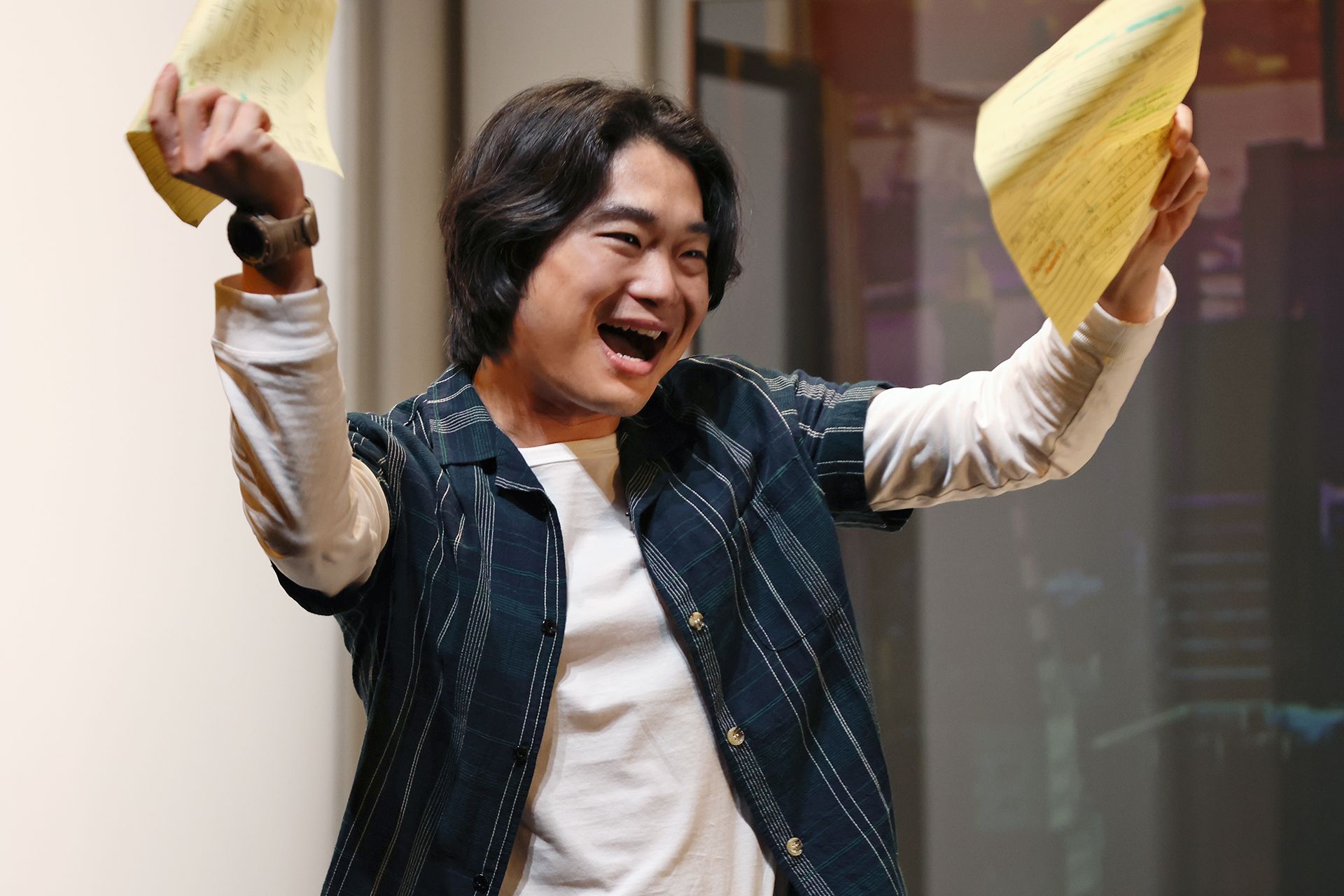

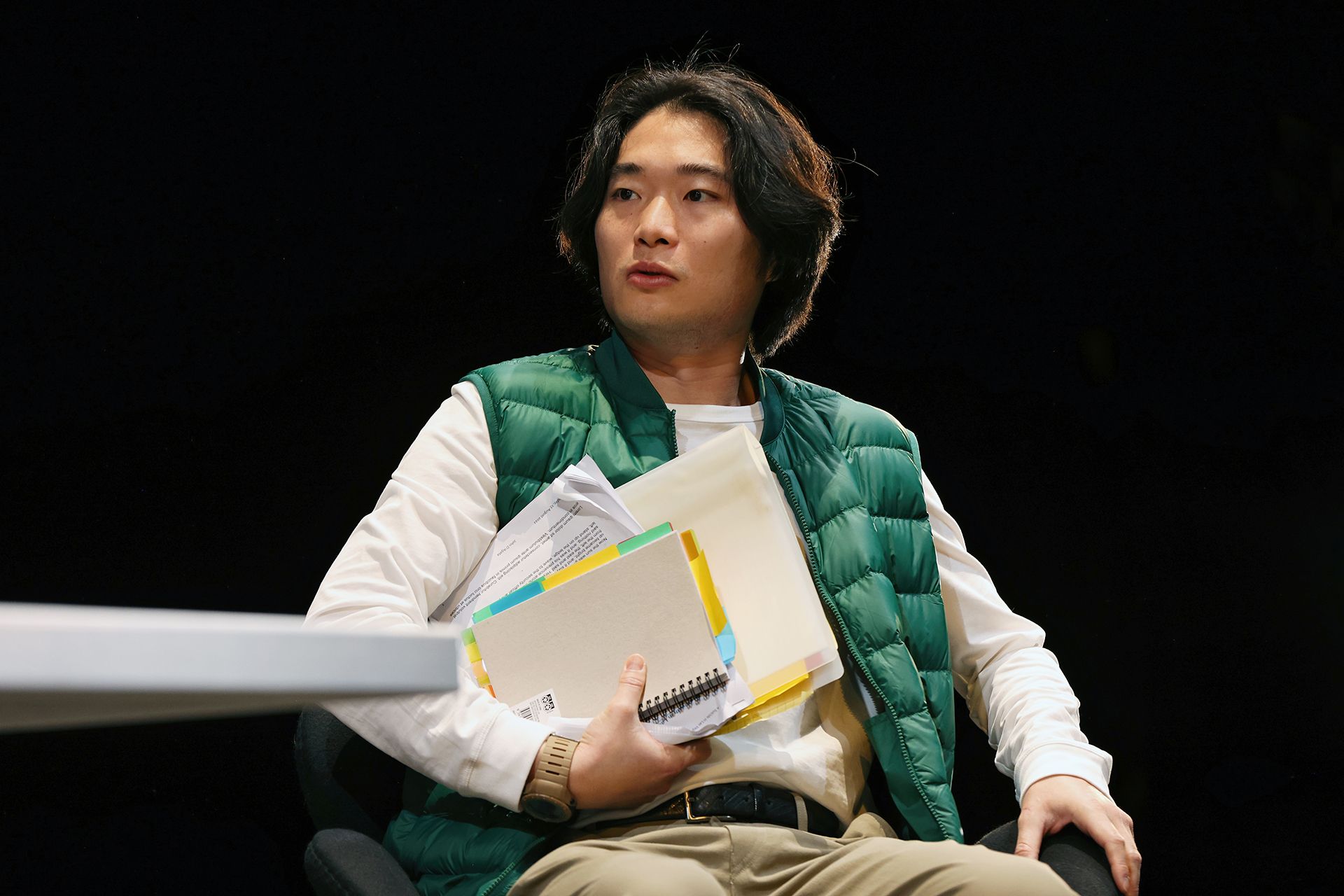

Ash Flanders is so incredibly theatrical, of course he has written a one-man play about his mother dying, even though Heather is somewhere in Melbourne, still quite alive. End Of begins with anecdotes about Flanders’ stint working as a transcriber for the police, then veers off talking about his adventures in procuring horse entrails to use as props for a show, and then his first moments on psychedelics that lead him to becoming sisters with a papier-mâché rooster. The pieces are tangential to say the least, but it is hard to care too much about coherence, when the point of the work is really only about Flanders’ immense comedic talent as a live performer.

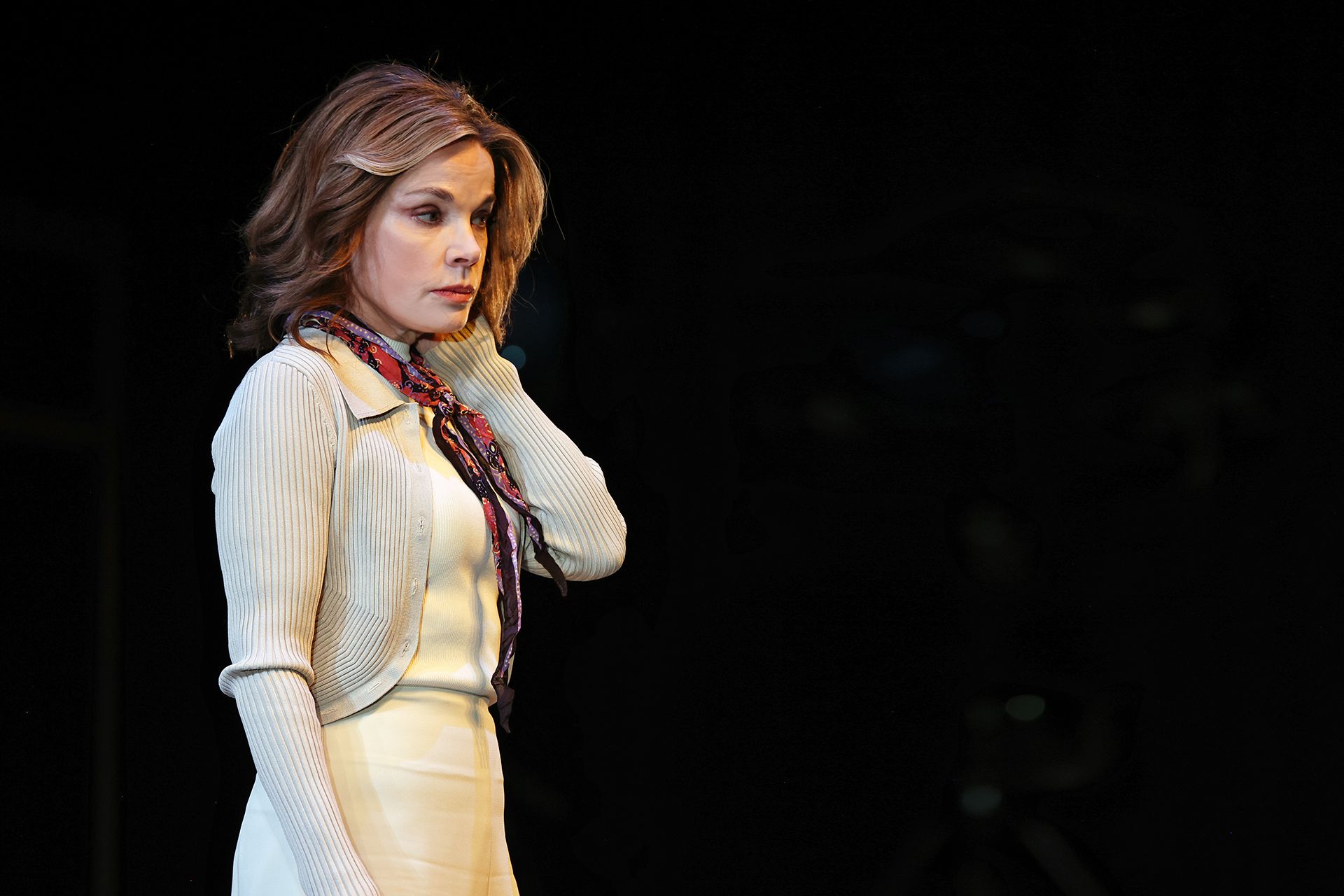

Magnetic and utterly persuasive, Flanders proves himself an actor of audacious talent and skill, in this piece named after his sardonic mother’s favourite punchline, End Of. It attempts to take us somewhere profound in the final minutes, but it is Flanders’ relentless obsession with the frivolous and the flamboyant, that leaves an impression. Director Stephen Nicolazzo knows this, and has made sure to build a production around that invaluable sense of humour, for an experience that provides incessant laughter, and endless amusement. Everything is fair game, from the disappointing Hollywood remake of Total Recall, to deaths in Flanders’ family. Camp becomes a sort of zen outlook, occupying the centre of Flanders’ world; if everything is capable of being diminished, nothing really hurts.

Stage and costume design by Nathan Burmeister is simple, but knowing, able to give a wink-and-nudge, that indicates appropriate time and place as well as attitude, for this very 21st century representation of ironic gay sensibility. Rachel Burke’s lights are a pleasant surprise, as they turn increasingly opulent, after establishing something distressingly humble, when we first meet Flanders at a bureaucratic facility. Sound by Tom Backhaus offers valuable atmospheric embellishment to the reminiscences being shared, even if Flanders’ extraordinary dexterity with his commanding voice, feels to be more than sufficient.

End Of is a reminder that sometimes, the story is not the thing. The sheer pleasure of being in the presence of a performer at the top of their game, doing what they do best, is one of the gifts of theatre that can never be replaced. This bliss cannot be digitised.