Venue: Capitol Theatre (Sydney NSW), from Jun 14 – Dec 24, 2023

Book: Linda Woolverton

Lyrics: Howard Ashman, Tim Rice

Music: Alan Menken

Director: Matt West

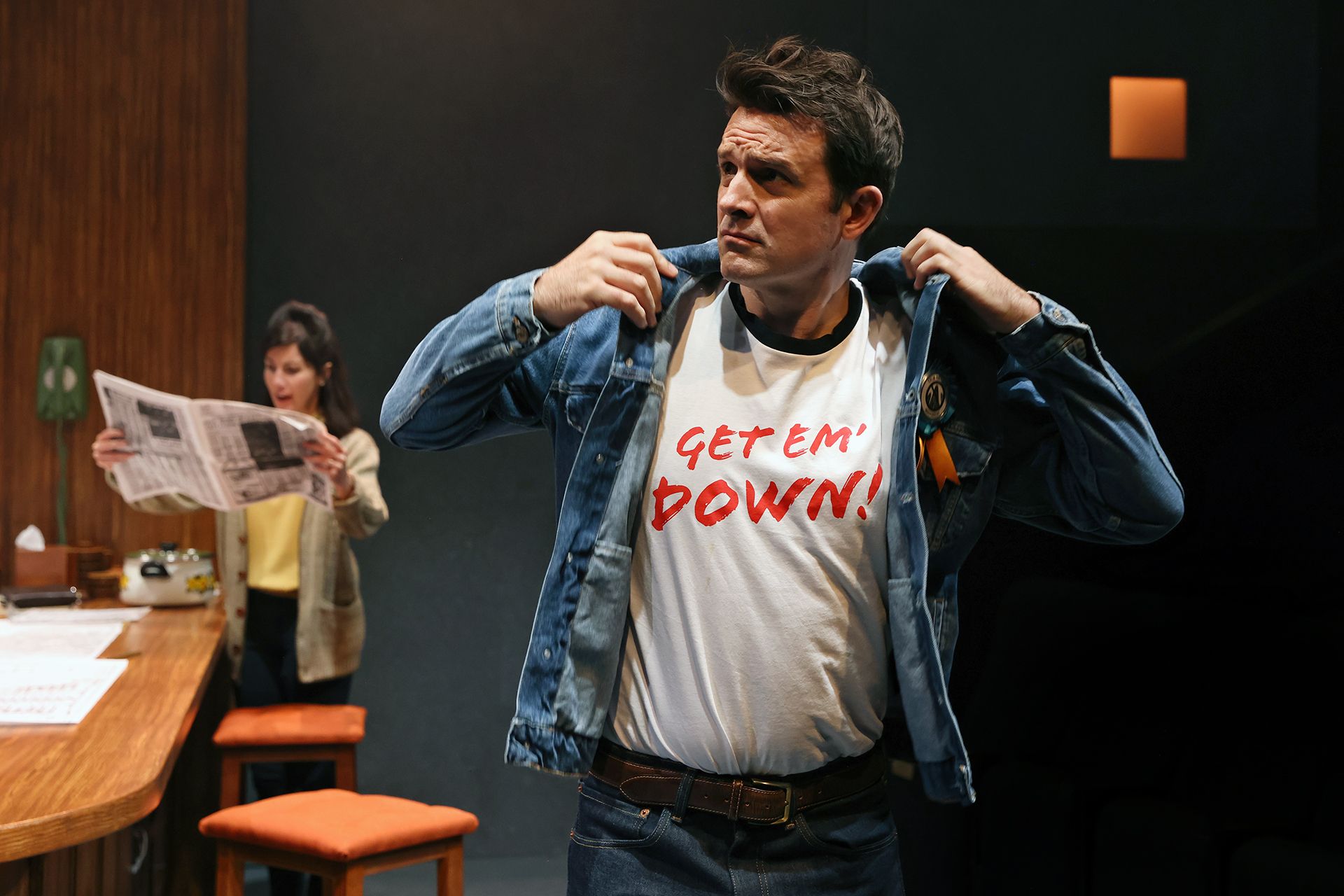

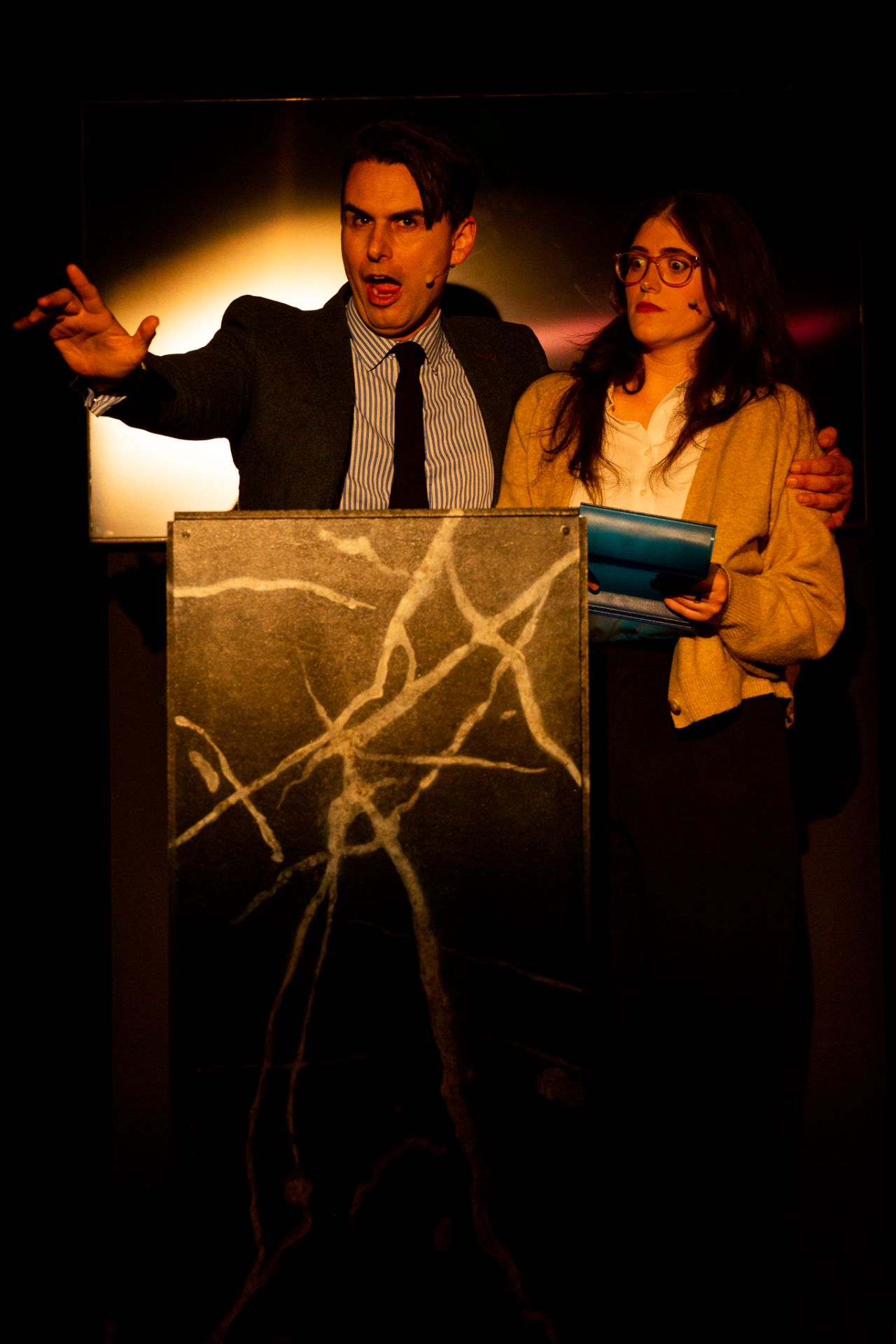

Cast: Rohan Browne, Nick Cox, Rodney Dobson, Jackson Head, Gareth Jacobs, Shubshri Kandiah, Hayley Martin, Orlando Steiner, Alana Tranter, Jayde Westaby, Brendan Xavier

Images by

Theatre review

Belle is an avid reader, who lives an idyllic life with her father in a village somewhere in France. Just as she begins to express the need for something more, adventure descends upon her simple provincial existence, when her father is held captive in the castle of the abominable Beast. This stage musical version of Beauty and the Beast first appeared on Broadway in 1994, when the Disney corporation had begun to deviate from the damsel in distress narrative. Even though Belle finds love in a prince, we are thankful that her sense of identity extends far beyond romance and marriage.

Revisiting the show in 2023, it is Belle’s strength and independence that truly resonates. The production benefits greatly from advancements in technology over these three decades, for some seriously spectacular staging especially notable in the world famous “Be Our Guest” number among others, but the effectiveness of the show is essentially predicated on a narrative about the celebration of humanity. All Beast and his servants want, is to become human again. All Belle wants, is freedom for herself and for her father. It turns out that love is the phenomenon that delivers for everyone at the end, but we know that humanity is the real and fundamental concern in Beauty and the Beast.

Exceptional stage craft in this production, offers an unparalleled experience of theatrical magic, capable of delighting even the most jaded of audiences. It delivers the kind of sensation that no other art form can; the thrills from witnessing live performance at this level of accomplishment, is quite transcendent. The artistry of a musical performer though, remains crucial to its success, and its star Shubshri Kandiah is so electrifying as Belle, one could imagine the show being equally satisfying without all the extravagant trimmings, just as long as Kandiah is present to bring her astounding talent, skill and soulfulness to the piece.

Beast is played by Brendan Xavier, whose flawless singing has us completely bewitched, and is surprising with the tenderness he injects, into depictions of a new masculinity much more suited to our contemporary age. Jackson Head as the cocky Gaston is appropriately conceited and comical, with a precision to his work that proves to be highly engaging. The iconically flamboyant Lumiere is brought to glorious life by Rohan Browne, who demonstrates incredible charisma and power, virtually unmatchable in allure whenever he steps onto the stage.

Beast can only turn human again when he is touched by love. In order to survive this existence, we all go through processes of dehumanisation, where over time we become harder, colder, closed off and anesthetised. Romance will not be every person’s salvation, but we can fight determined, against that which wants to turn us brutal and unfeeling. People are capable of loving again, and layers of calluses can be removed, to reveal a weathered but stronger heart, ready for bigger and better.