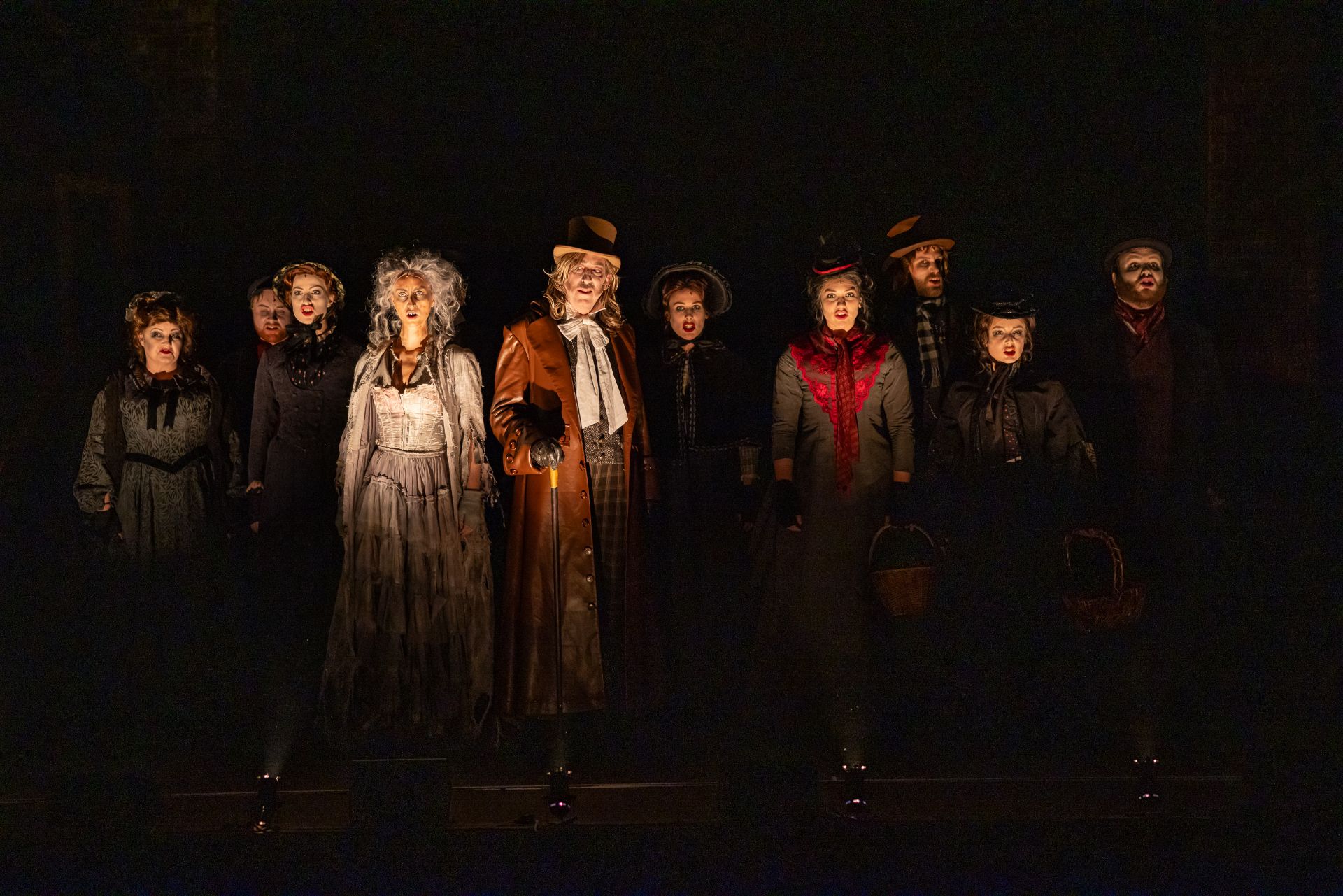

Venue: Sydney Opera House (Sydney NSW), Aug 17 – Oct 13, 2023

Music: Claude-Michel Schönberg

Lyrics: Alain Boublil, Richard Maltby Jr.

Book: Alain Boublil, Claude-Michel Schönberg (based on Madama Butterfly by Puccini)

Director: Laurence Connor

Cast: Abigail Adriano, Nick Afoa, Kerrie Anne Greenland, Kimberley Hodgson, Nigel Huckle, Seann Miley Moore, Laurence Mossman

Images by Daniel Boud

Theatre review

The 1989 musical by Boublil and Schönberg, Miss Saigon has become increasingly contentious, as creative communities grow to be more inclusive of minority cultures, and learn to be sensitive to perspectives of those traditionally marginalised. Based on Madama Butterfly by Giacomo Puccini from 1904, the germination of Miss Saigon was always from a place of pity, and by implication cultural superiority.

It is no wonder that the show is widely regarded by the Vietnamese diaspora to be problematic, not only because of the inherently patronising attitudes, but also of the stunning disregard for any people who wish to be considered more than pathetic, desperate or undignified. One may choose to take the view that the creators’ intentions seem to be about sympathy and solicitude, but there is no denying that the three main Vietnamese characters in the work, are nothing any viewer from any cultural background, would wish to aspire to. In the absence of any persons more respectable or indeed honourable, Miss Saigon represents a Vietnam that is essentially ignoble and debilitated, devoid of spirit and worth.

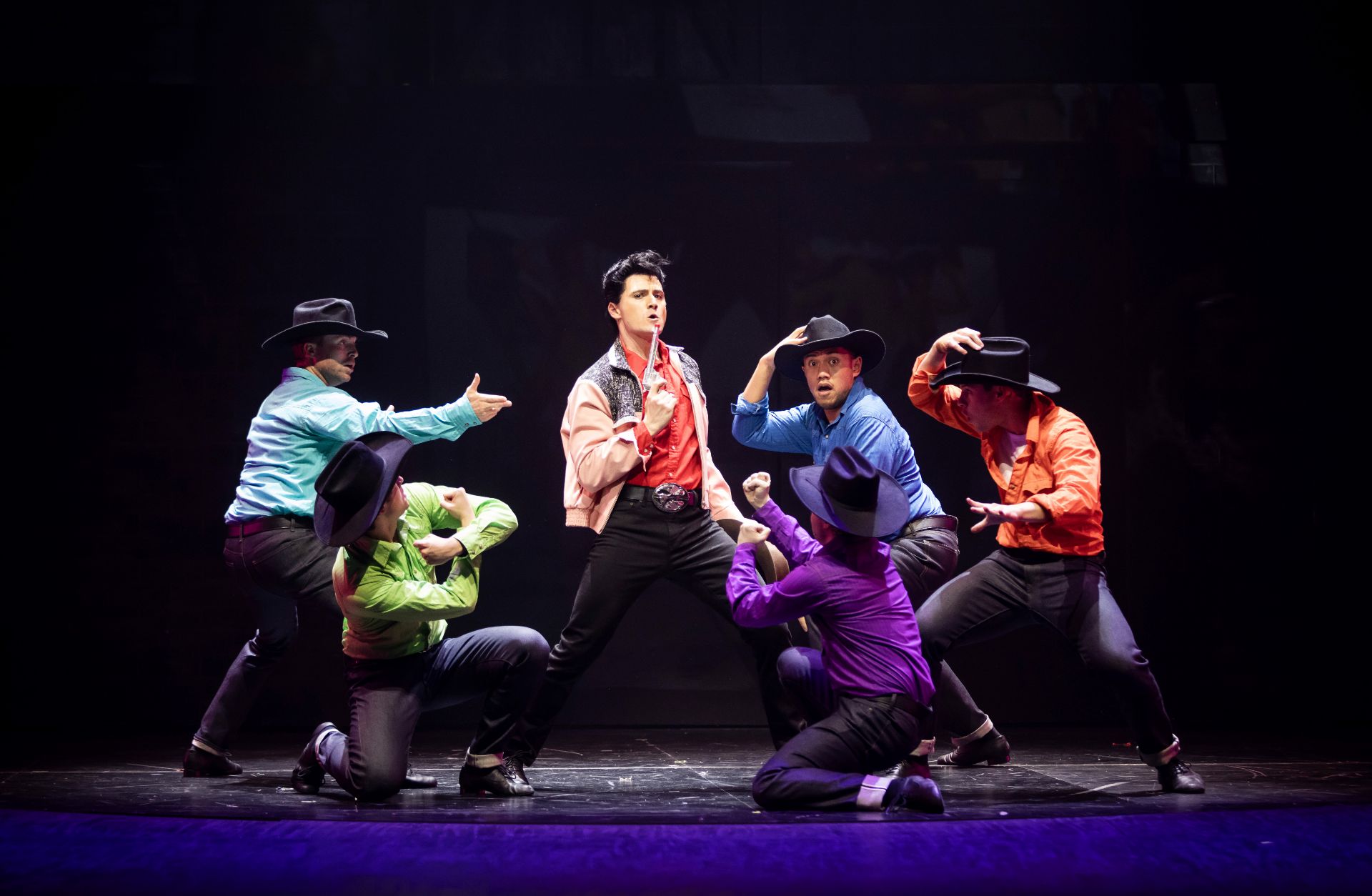

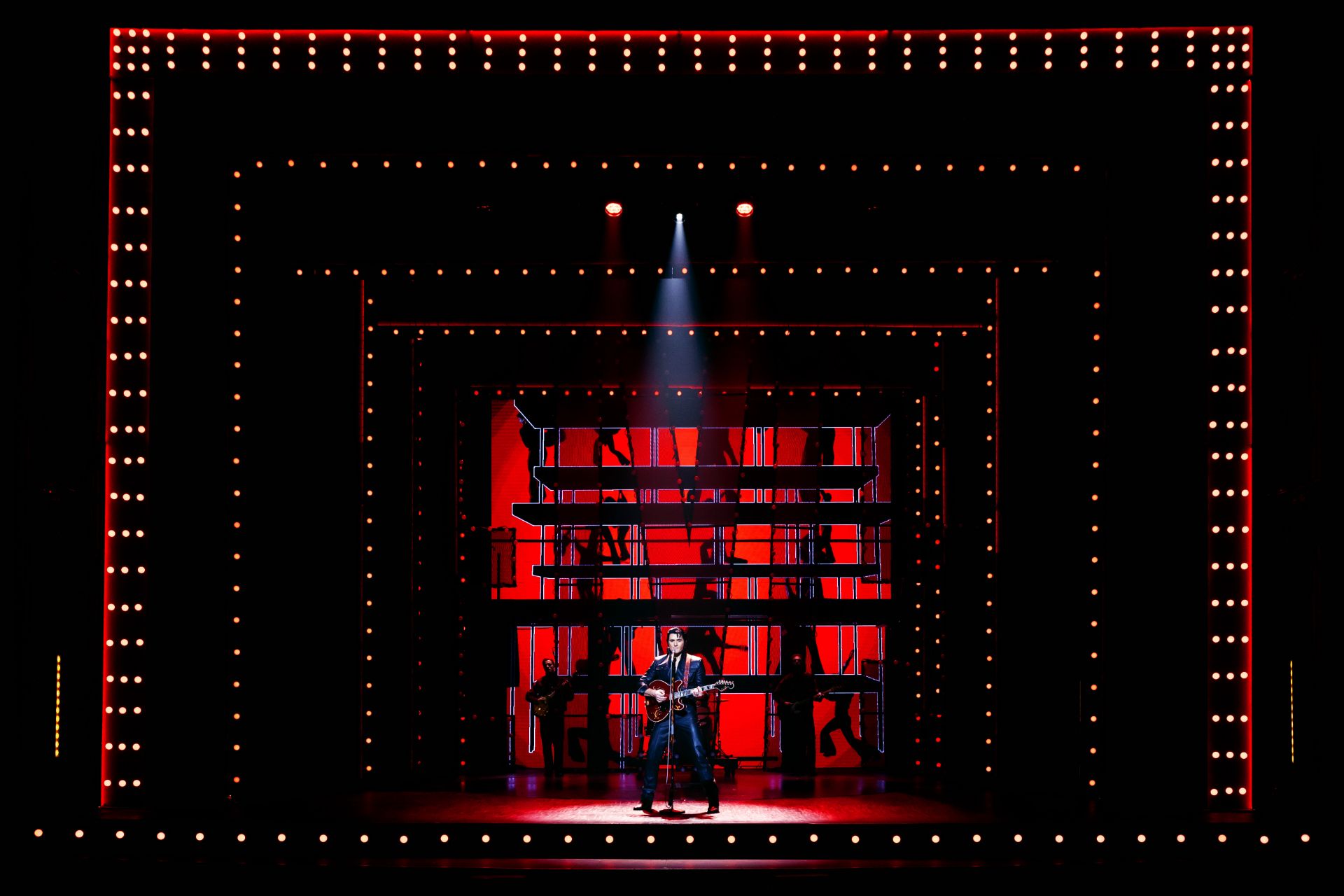

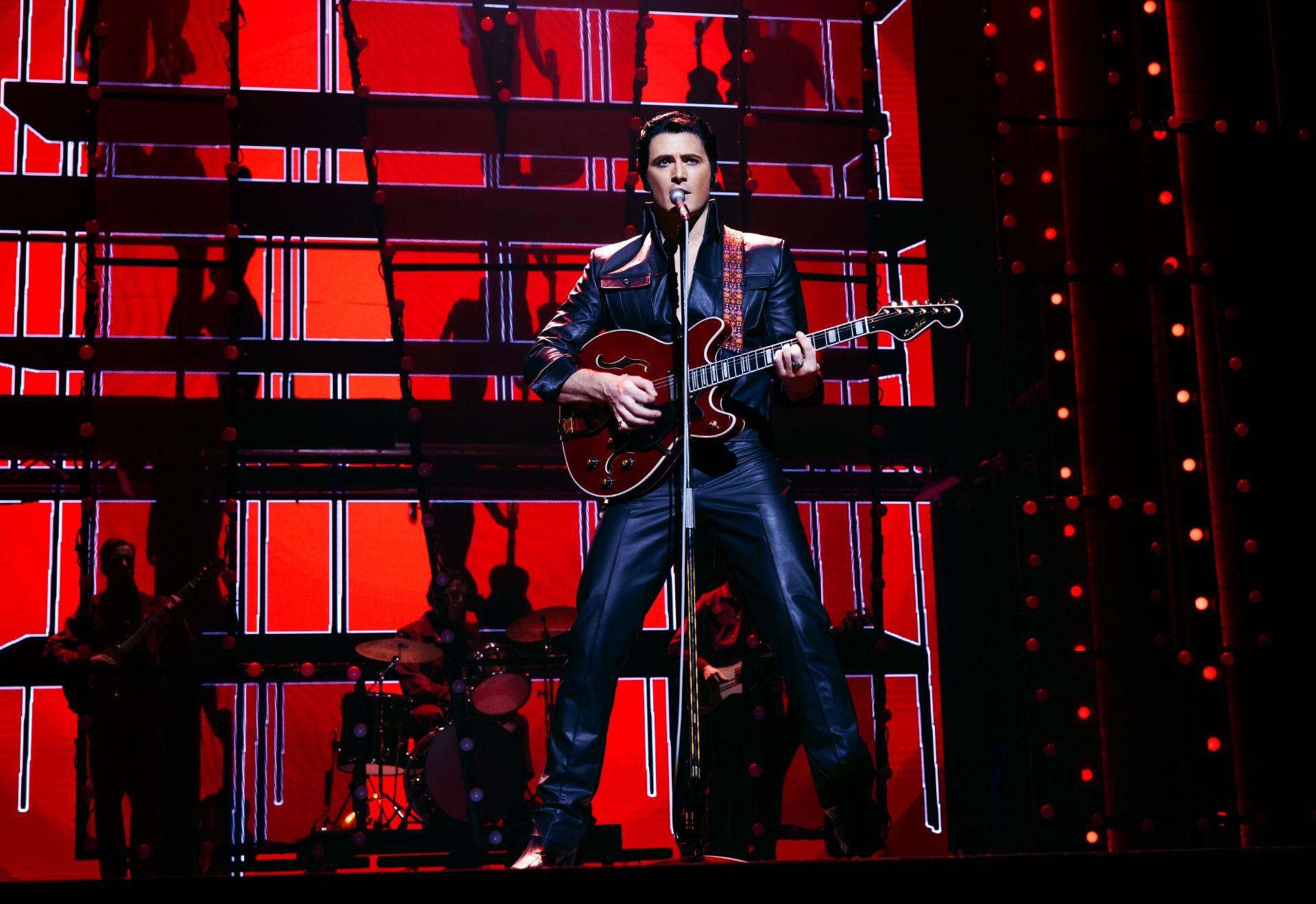

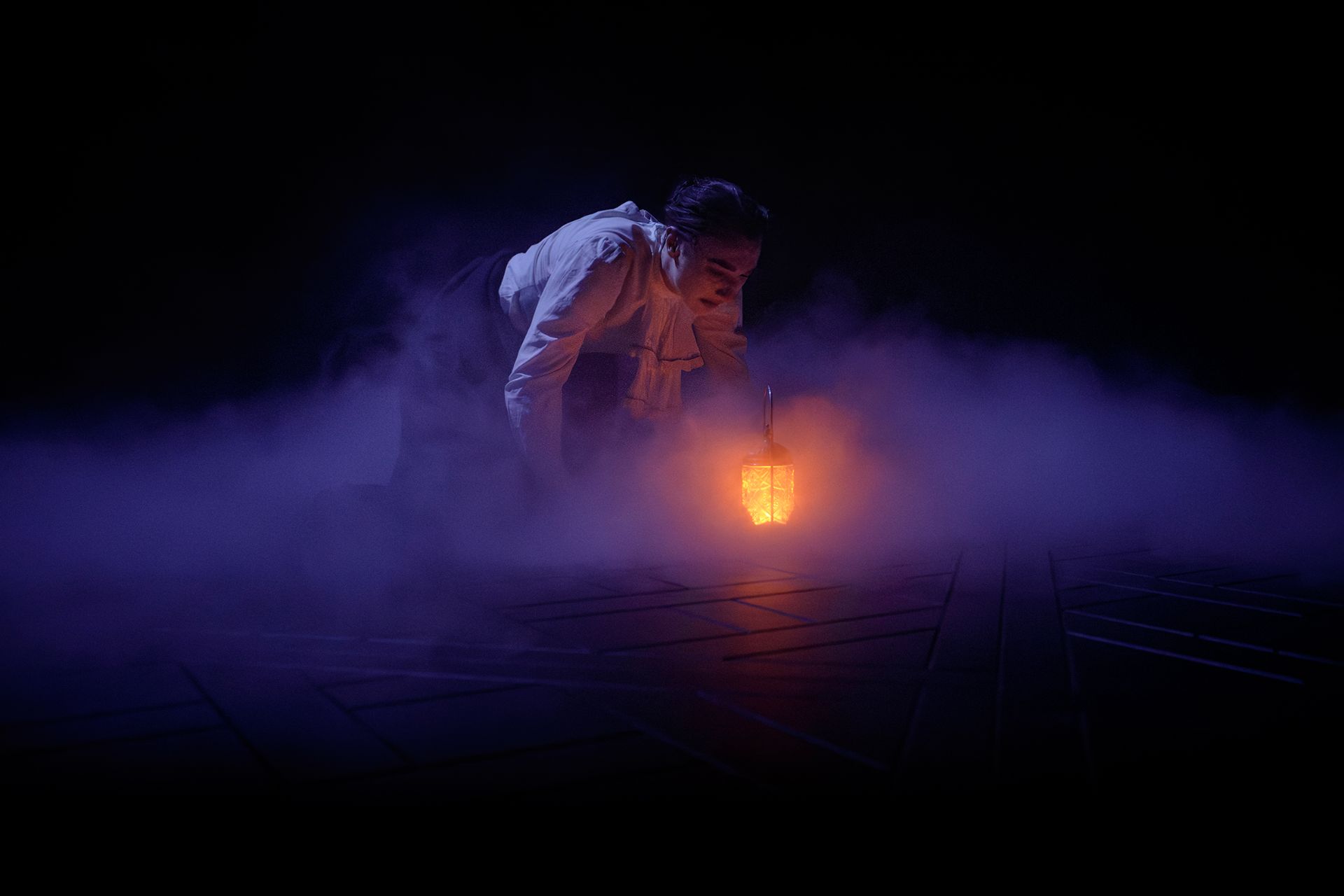

This revival, first presented 2014 in London, does little to address the contemporary concerns surrounding Miss Saigon. It retains the famed gimmick of a helicopter landing on stage, along with truly cringeworthy choreography appropriating military physicality of the “Yellow Peril”. Admittedly, lighting design by Bruno Poet is exquisitely rendered, and for this production, the orchestra is simply sensational, able to have us emotionally stirred throughout, even with all the absurdity of the most unbelievable love story.

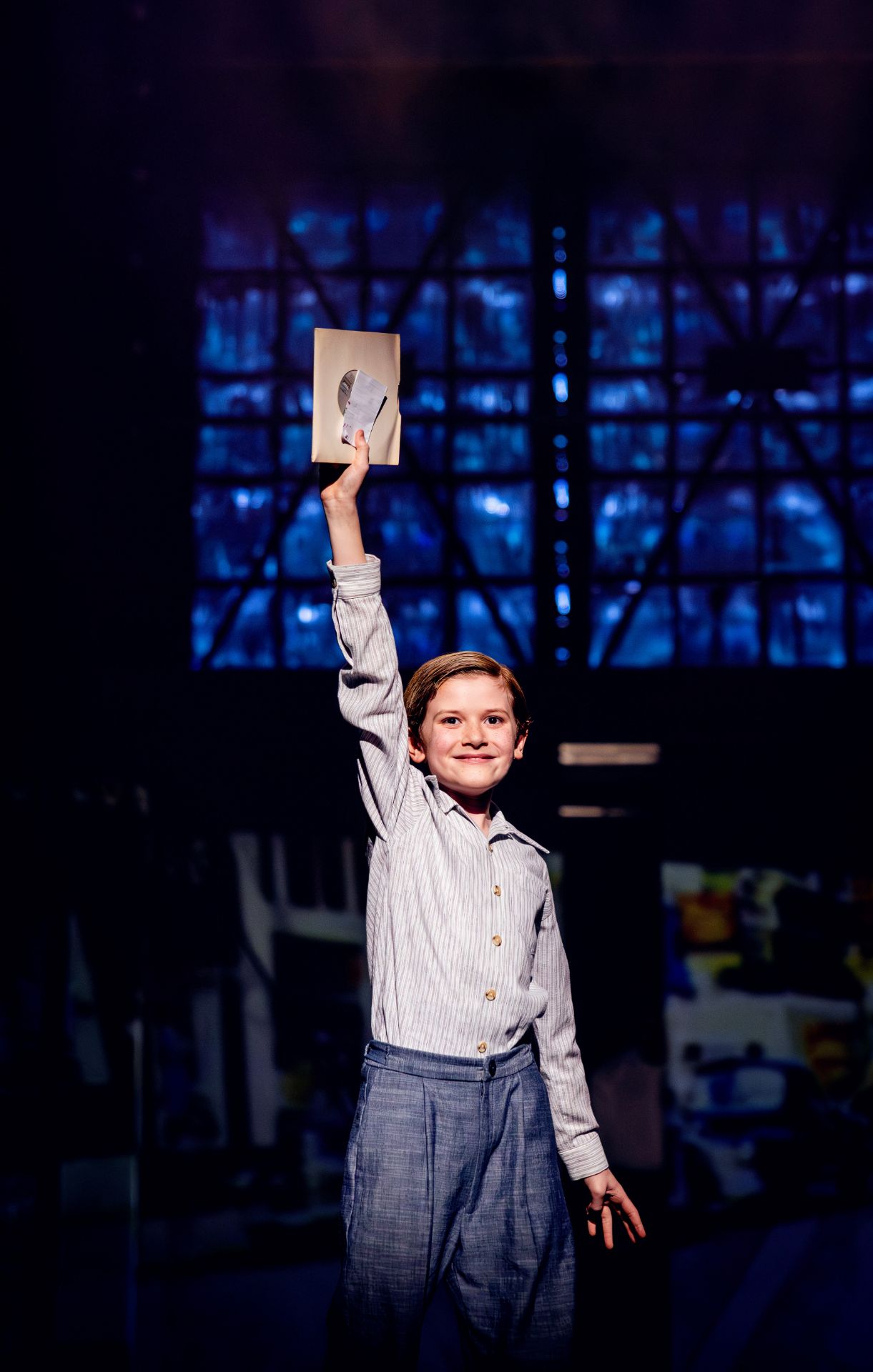

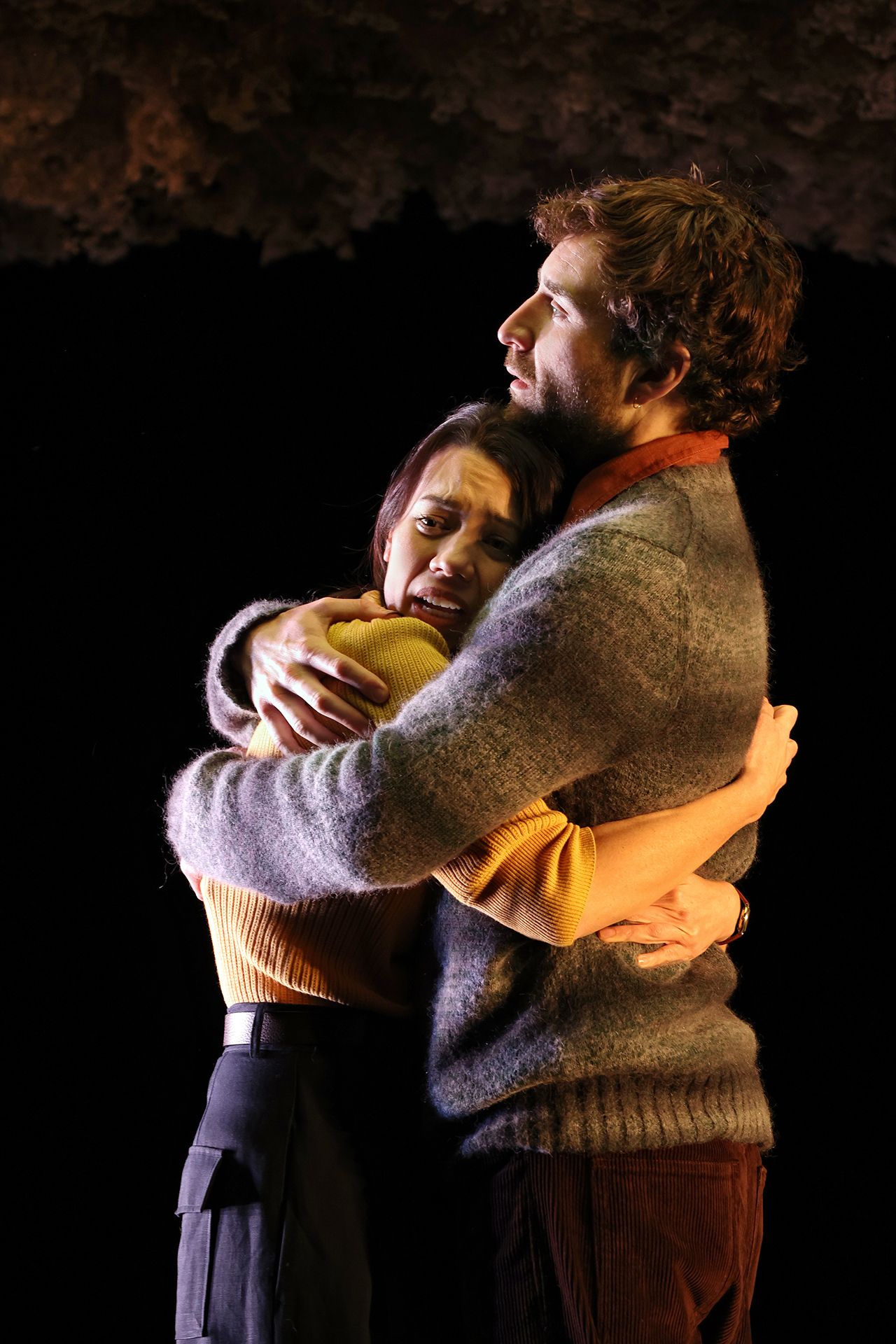

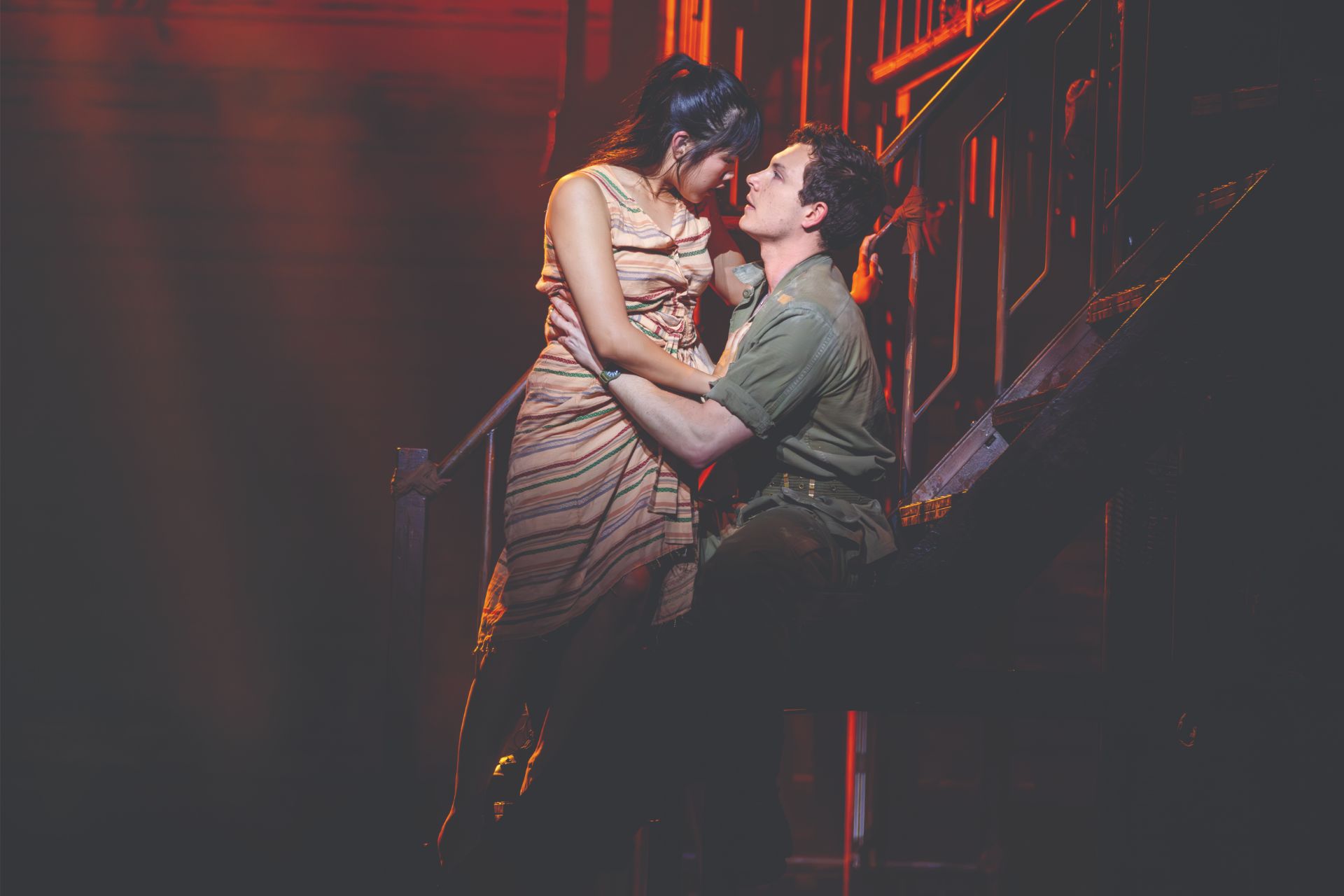

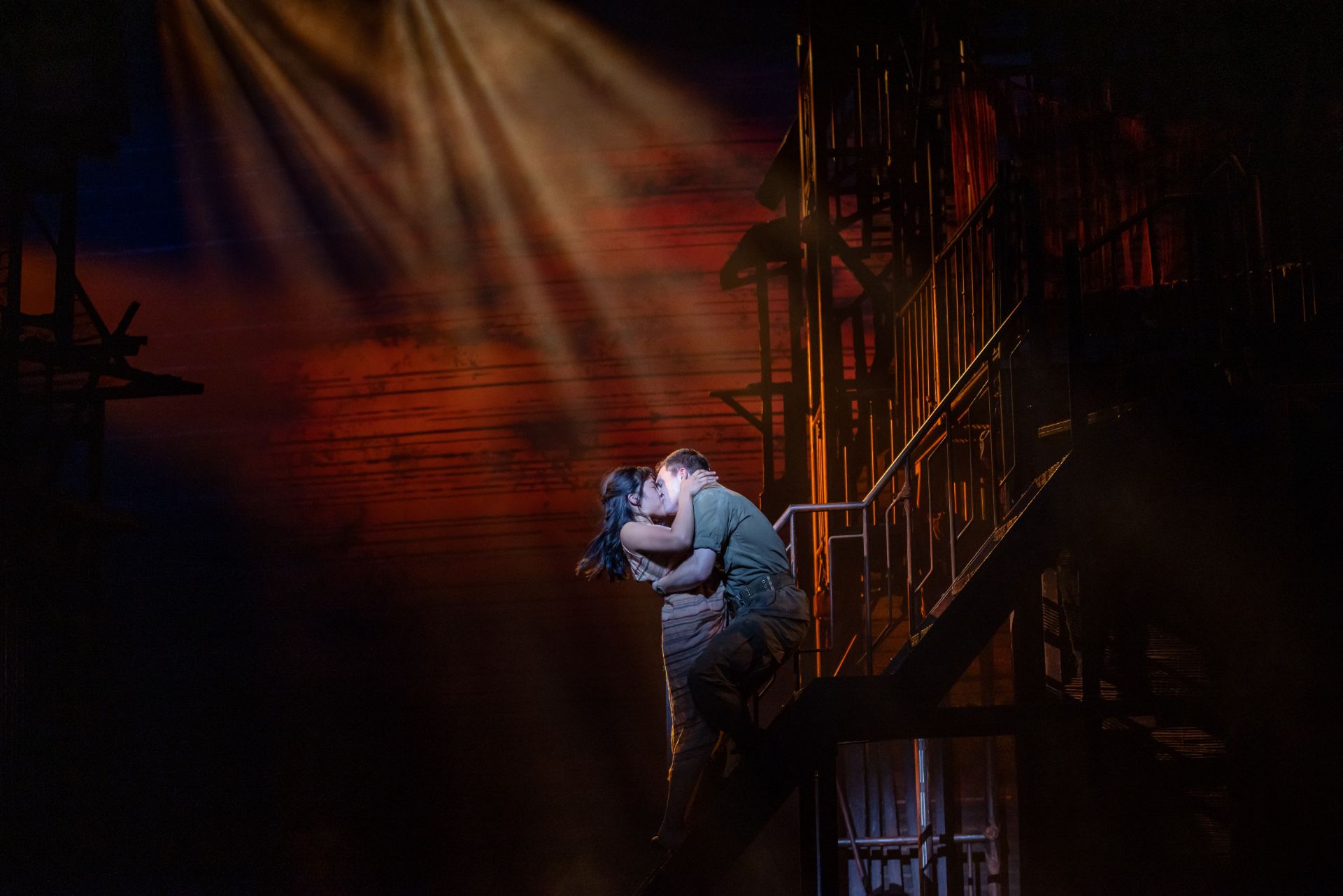

Performer Abigail Adriano too is spectacular as Kim, the embarrassingly hopeless romantic at the centre of this drama. Adriano’s voice is crystal clear and replete with power, singing every note to sheer perfection, and along with her fierce commitment to portraying verve and passion for the role, we are nearly convinced, if not by Kim’s narrative, then definitely by the utter intensity of her emotions.

Kim is almost but not quite heroic, in a show that wishes to paint her as admirable. Through a Western feminist lens, Miss Saigon is to be criticised for choosing to depict a woman of immense fortitude and strength, only as forlorn and sorrowful, a long-suffering lover and mother who can only meet with tragedy at the conclusion. Even if we are to believe in her sadistic tale, there are plentiful other parts to her life that should take precedence, ones that are independent of her brush with a Westerner, and ones that demonstrate the inevitable joy and humour that must exist in any person’s astounding capacity for survival in those circumstances. Instead, we only see Kim at her worst, before witnessing her completely gratuitous demise.

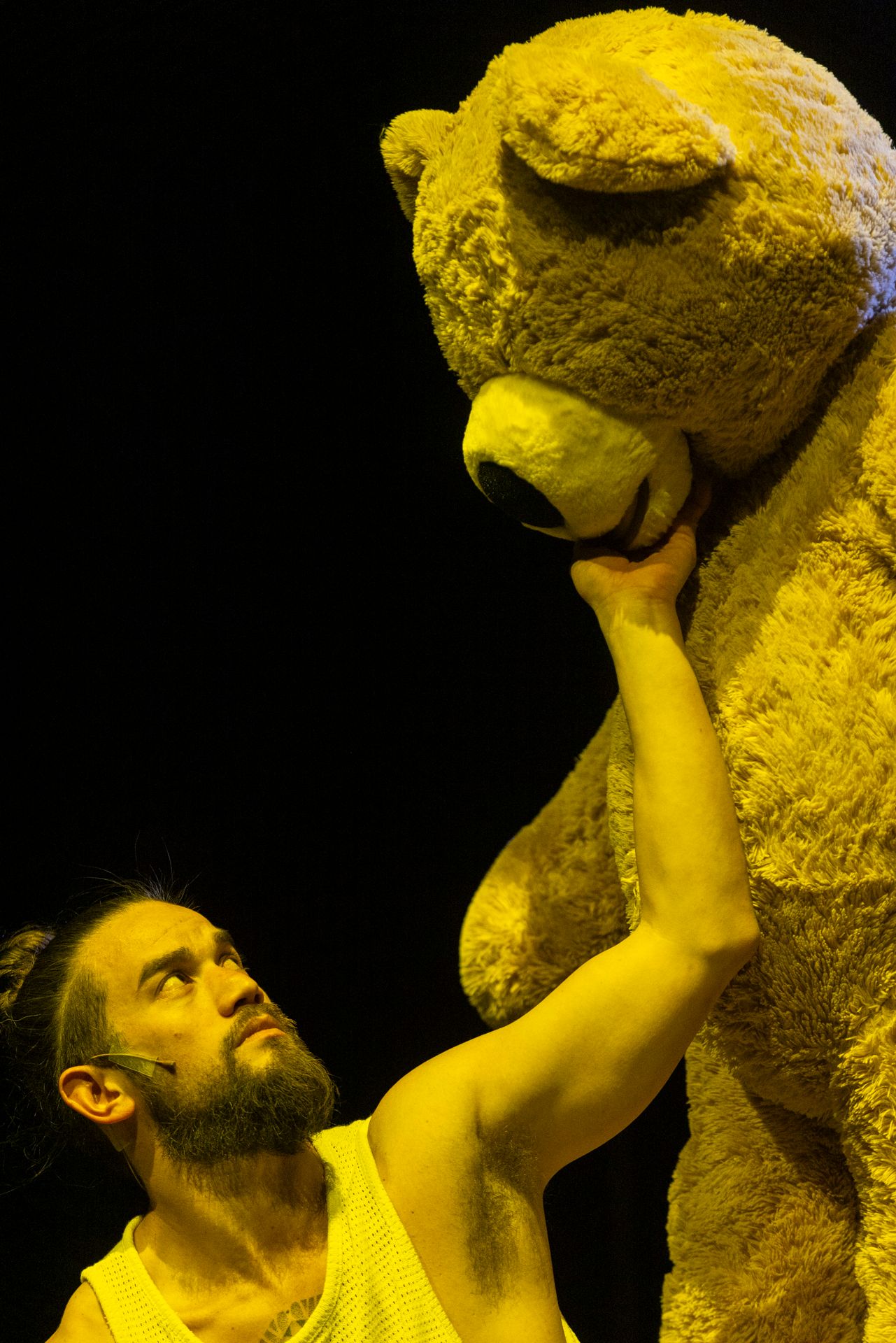

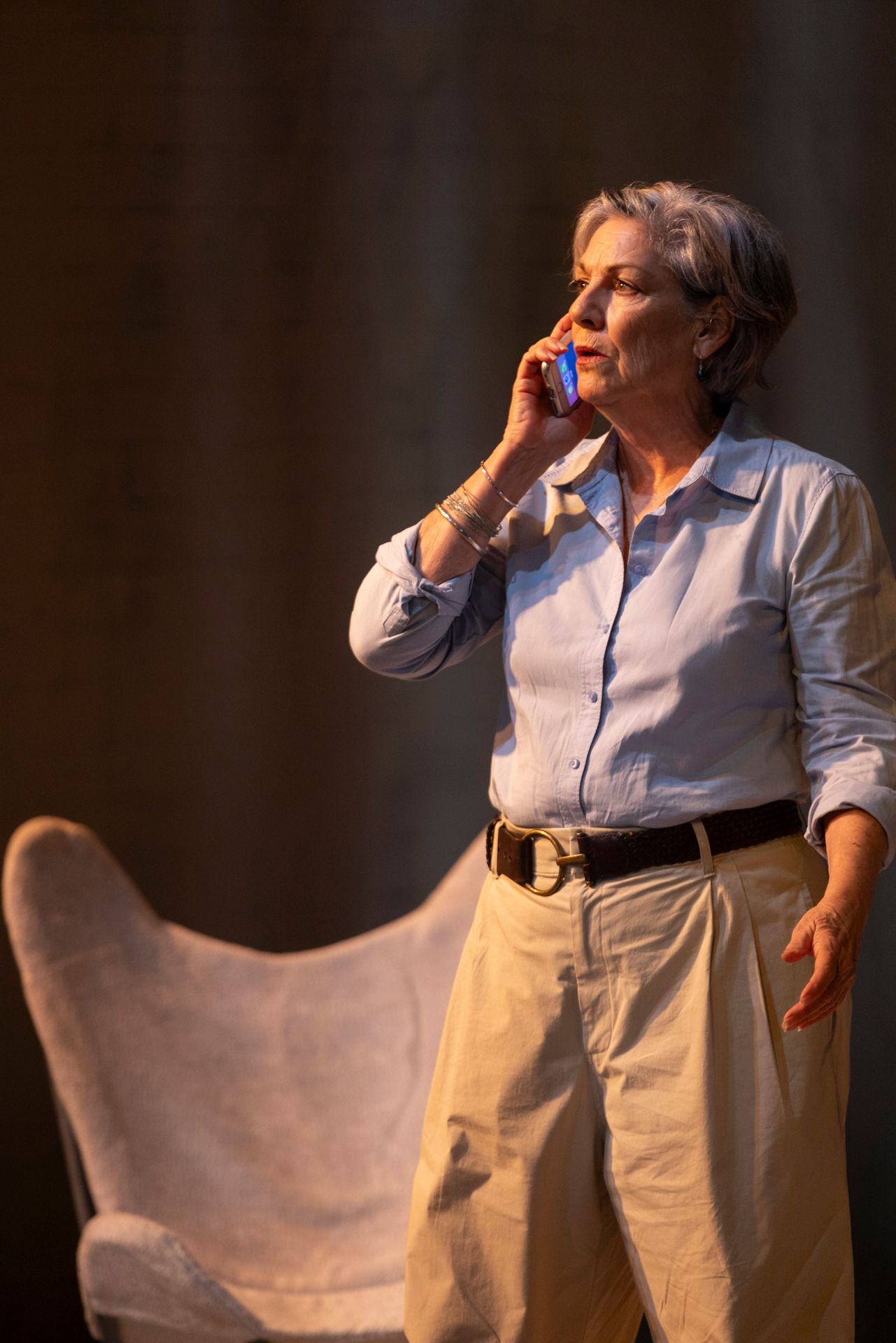

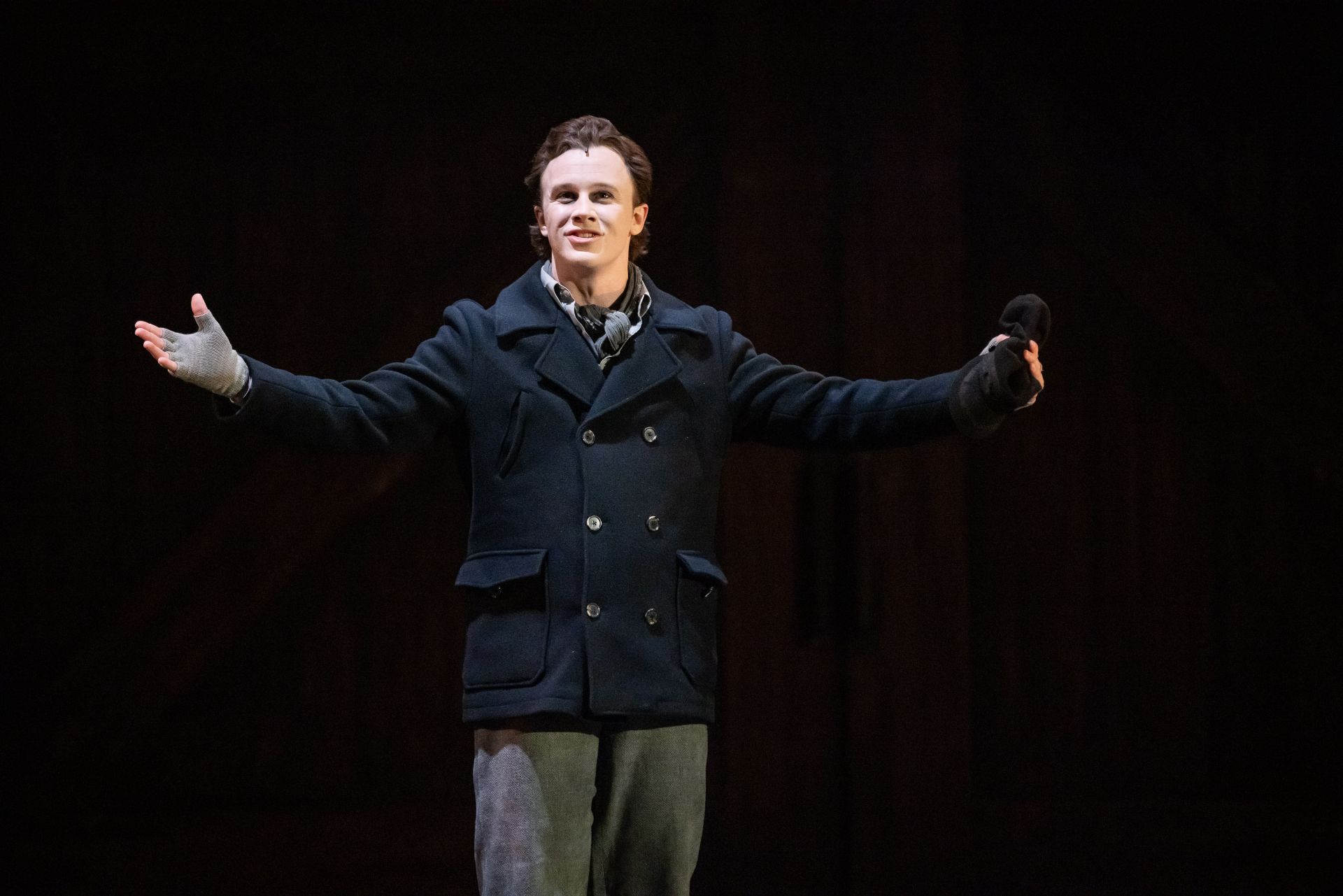

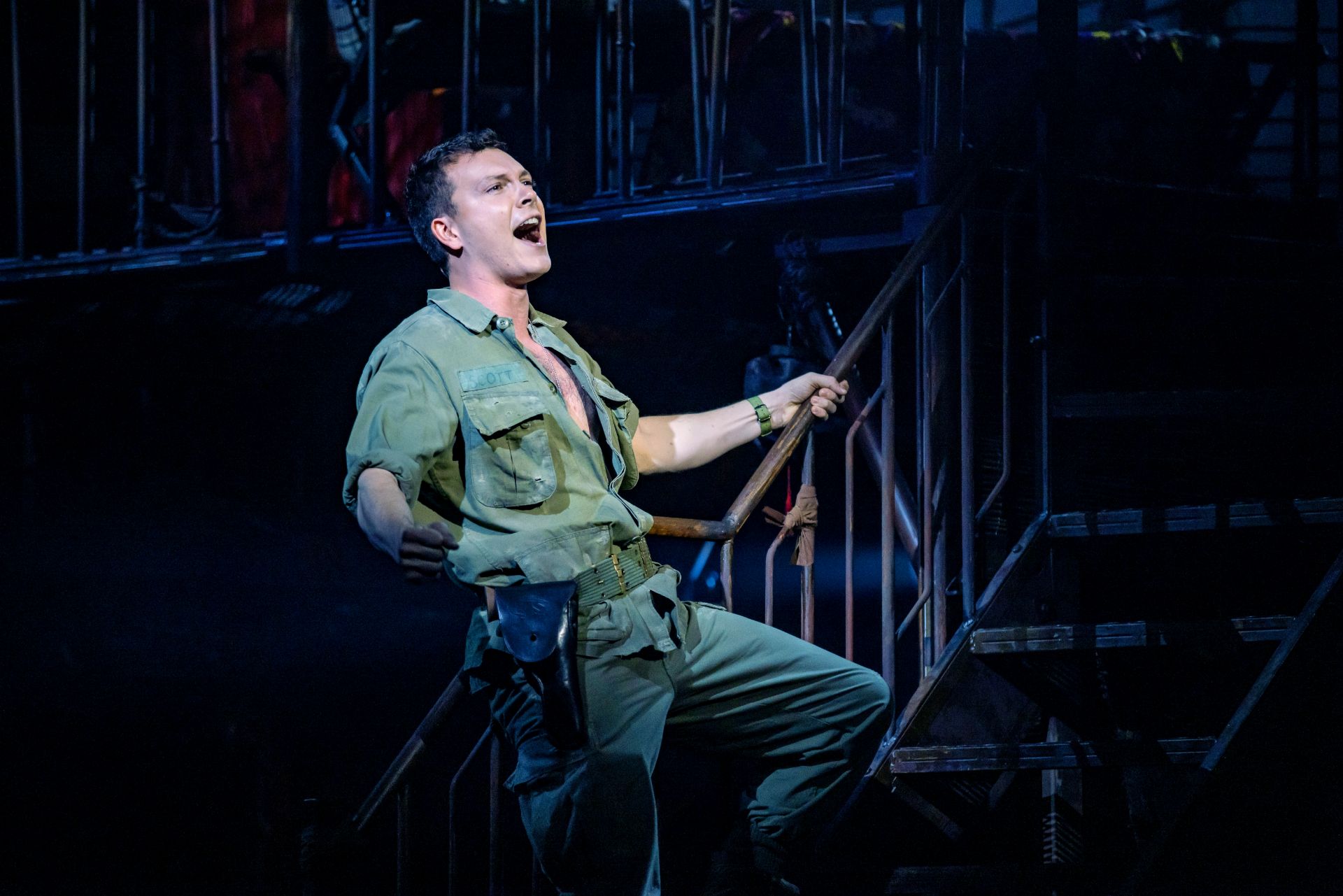

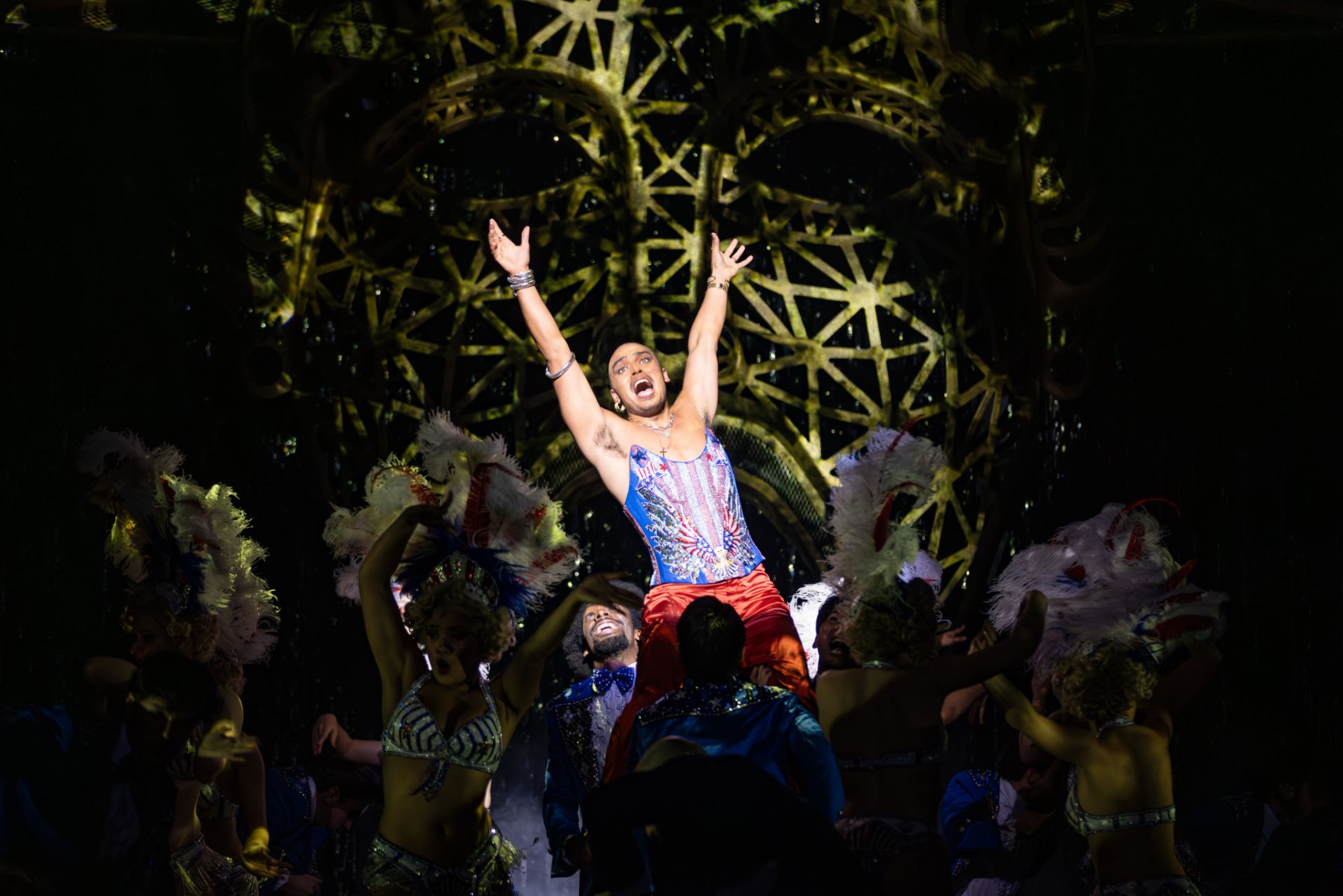

Other notable cast members include Nigel Huckle who plays Chris, the Pinkerton equivalent, with appropriate wholesomeness, in a work determined to have the straight white male offering the only beacon of light, in what is really a no-win situation. Laurence Mossman’s restraint as Thuy proves a valuable element, in something that revels in being overwrought and fantastical. The Engineer is played by Seann Miley Moore, who brings an excellent flamboyance, but who leaves the part feeling somewhat surface, unable to protect him from being mere caricature.

Musicals are big business, at least in the world of art. It makes commercial sense to bring Miss Saigon back, if the main intention is financial, and indeed survival, for the many individuals and organisations involved. This argument is however, too convenient. Those who choose to work in the arts, should not be forgiven for putting money ahead of the socio-cultural impact their work may bring. There are many professions that are unashamedly about the pursuit of material wealth, and making art is simply not one of those. The artist’s life is hard, not only because the very nature of creativity and invention is difficult, the artist has to always prioritise their search for truth and meaning, over any desire for wealth and esteem. Certainly, the artist must participate in activities that are less than idealistic, there are countless opportunities for one to compromise, but when the damage can be deep, as in this case involving ongoing trauma from a widely reverberating calamity, we simply have to say no.