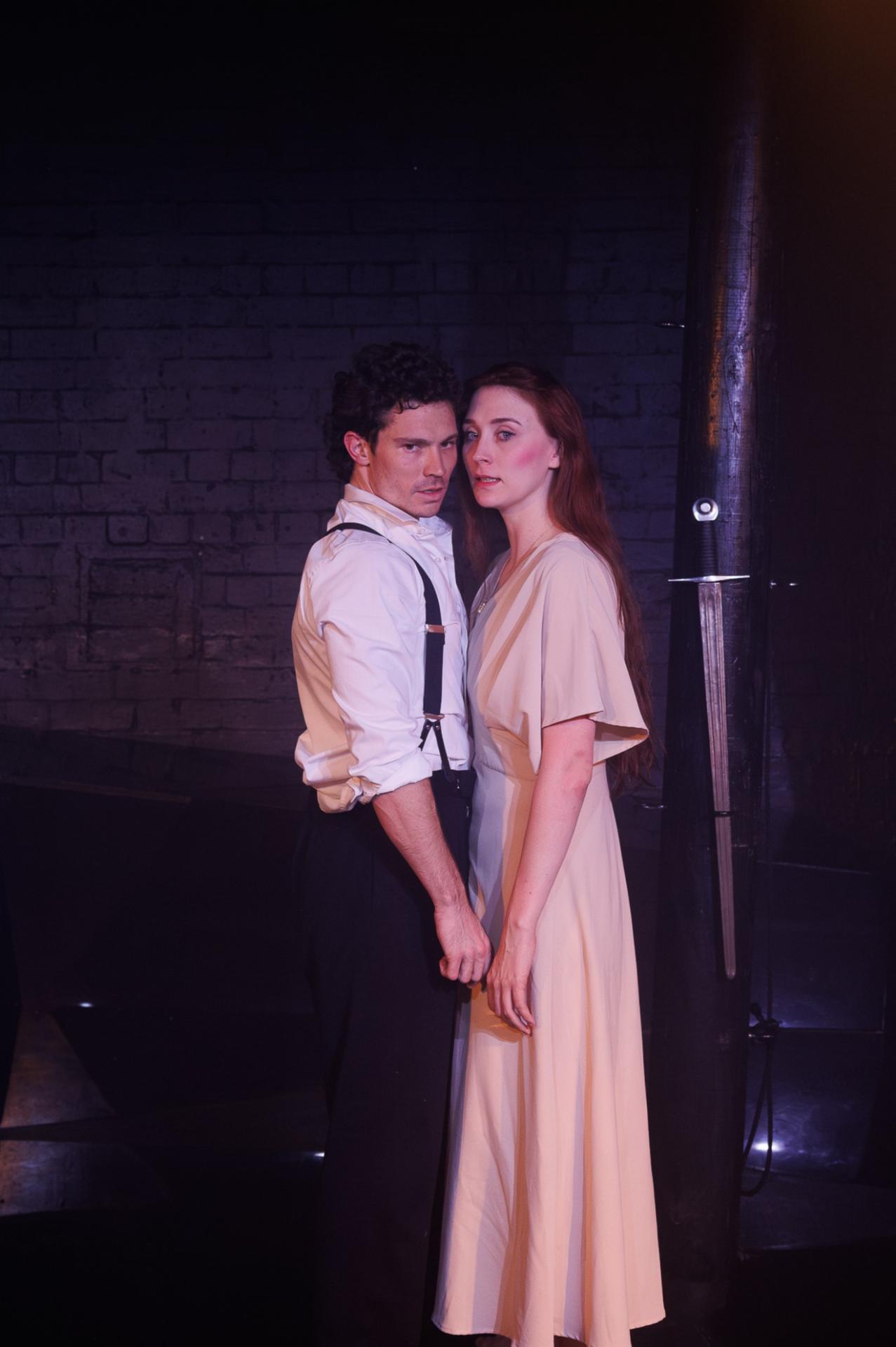

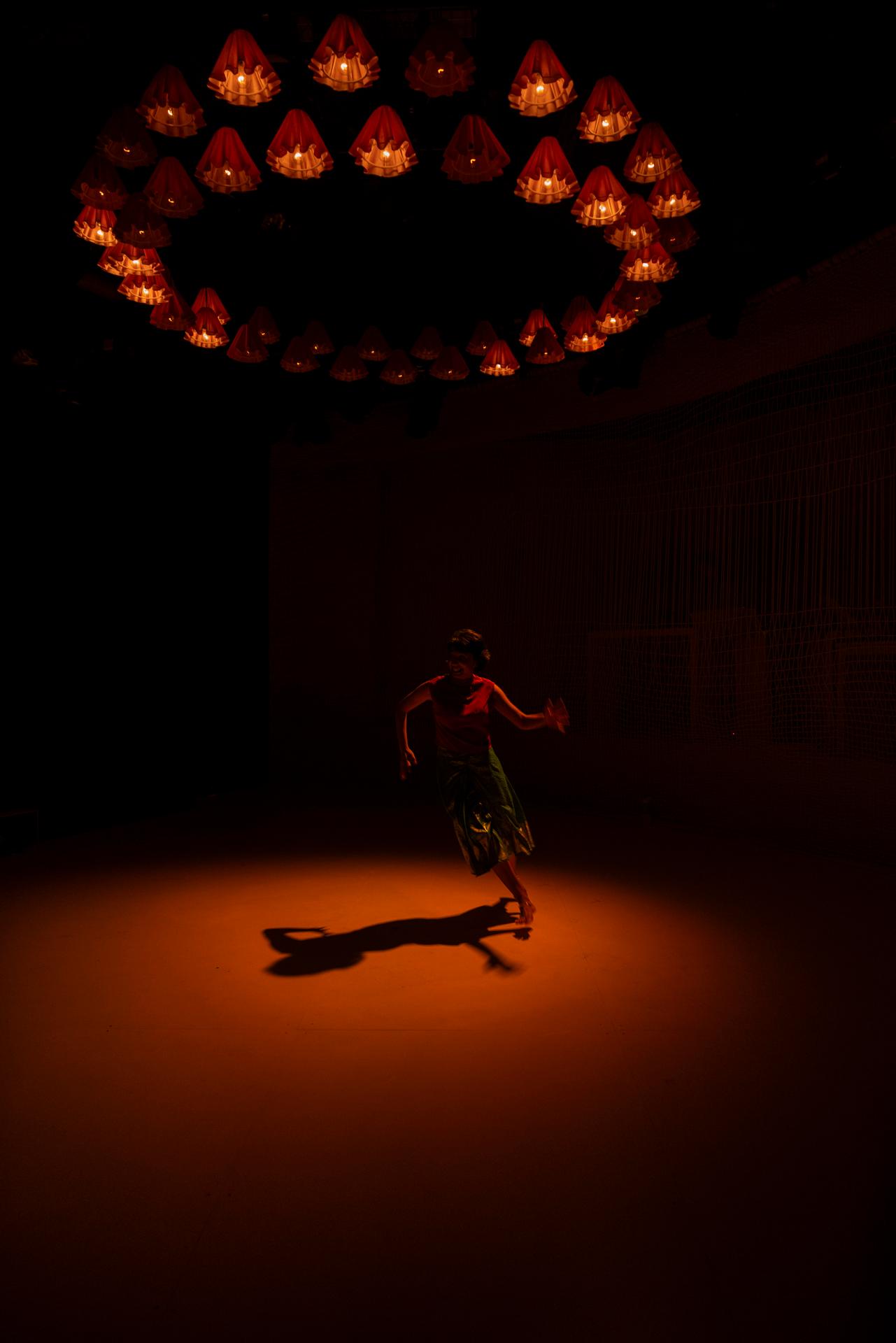

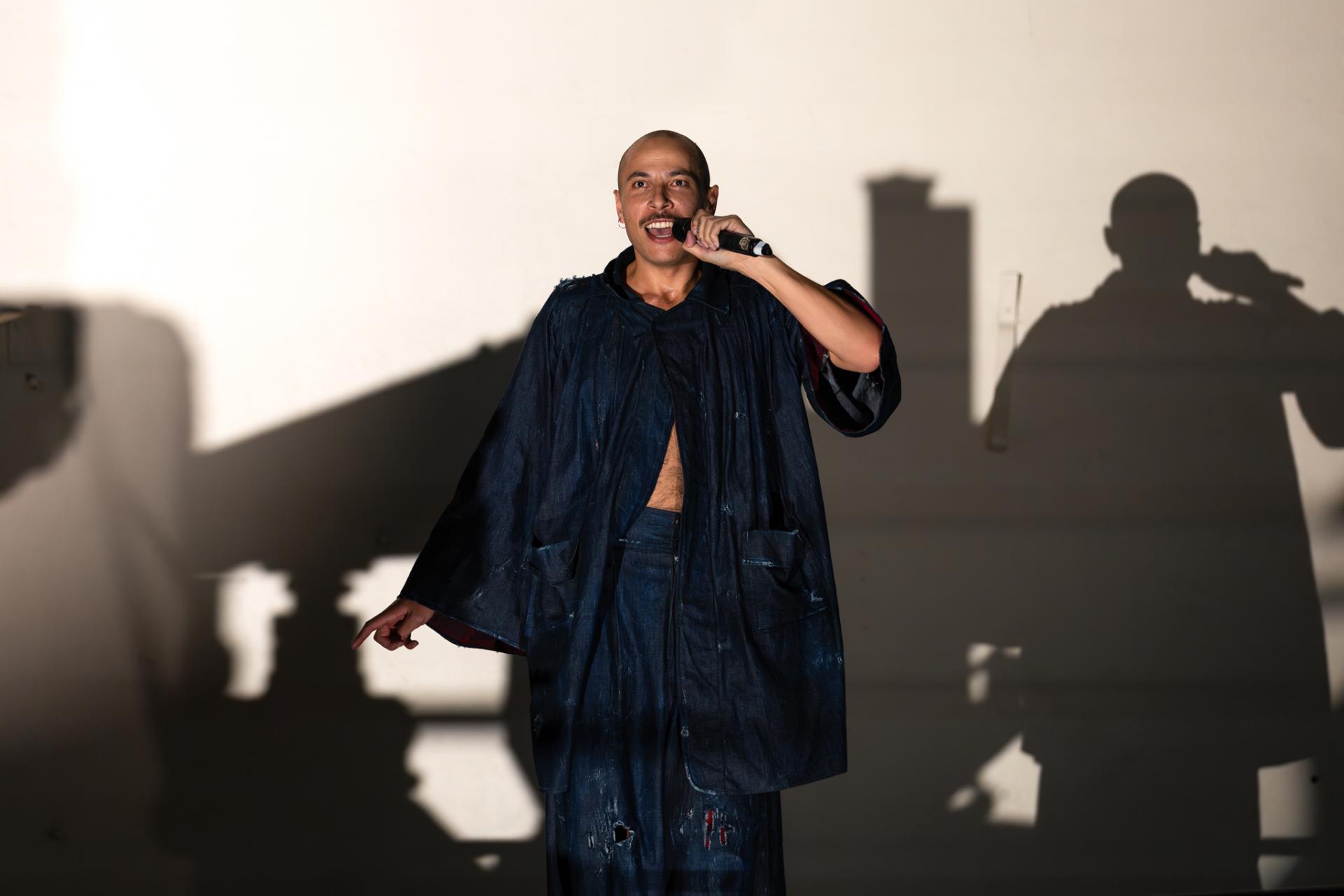

Venue: KXT on Broadway (Ultimo NSW), May 3 – 18, 2024

Playwright: Isabella Reid

Director: Mathew Lee

Cast: Lib Campbell, Clay Crighton, Lincoln Elliott, Paul Grabovac, Teale Howie, Mark Langham, Linda Nicholls-Gidley, Rachel Seeto, Annie Stafford, Michael Yore

Images by Clare Hawley

Theatre review

There has been a death in the Glynne family, and all the kin congregate to hold a vigil for the dearly departed. In Isabella Reid’s Misery Loves Company, we see everything go incredibly wrong, for an uproarious comedy, set in what should be the most sombre of times. With it being 1977 in Northern Ireland, and turbulence a permanent fixture during those years, perhaps chaos does make sense, even in moments of reverence and intimacy.

The jokes are plentiful, and indeed incessant, in Reid’s debut play. Misery Loves Company is full of mischief, with sharp dialogue and short scenes, that keep it a buoyant experience. Director Mathew Lee imbues a bold spontaneity, for a show that feels as fresh as it is amusing, consistently enjoyable with its resolute focus on delivering laughter. The cast of ten is strong in general, with a respectable amount of emphasis on chemistry between performers, that ensure we can all be swept up in the effervescent tomfoolery.

Production design by Ruby Jenkins is commendable for its sense of accuracy in terms of portraying a precise time and place, and also for a visual vibrancy that contributes to the humour of the piece. Lights by Tyler Fitzpatrick are deployed with an impressive eye for detail, notable for their ability to manufacture subtle but meaningful shifts in mood. Clare Hennessy’s music demonstrates an impressive sophistication, as it evokes cultural specificity and a gently melancholic nostalgia, for a presentation that for some, relates to a cherished tradition. We come from all corners, but where we converge on this land, is often in the sheer absurdity of living through together, each and every mercurial day.