Venue: KXT on Broadway (Ultimo NSW), Feb 11 – 15, 2026

Playwright: Grace Wilson

Director: Jo Bradley

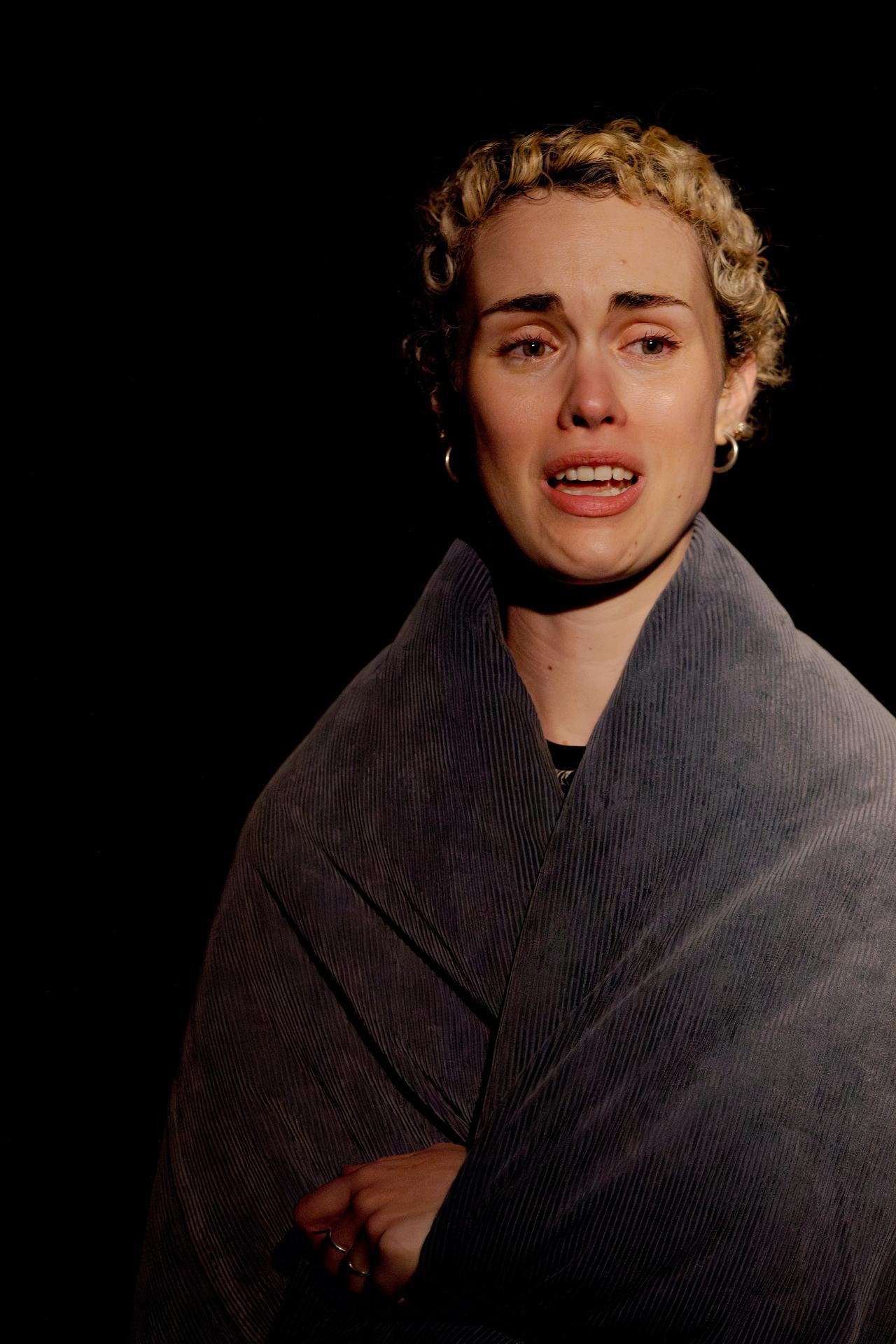

Cast: Annie Stafford

Images by Phil Erbacher

Theatre review

Gia is desperate to play Ophelia in Hamlet at Sydney’s premier Shakespeare company, yet at twenty-nine she confronts the dawning realisation that this ambition will likely remain unfulfilled. At home, her boyfriend Dan pressures her toward motherhood, rendering their relationship increasingly transactional. In Grace Wilson’s Gia Ophelia, we witness an actor gradually overwhelmed, drowning in disappointment and sorrow—much like the role she covets most.

Wilson’s dramaturgy emerges as the earnest offspring of Shakespearean inspiration, whilst simultaneously offering a laceratingly frank excavation of a young woman’s interiority in the contemporary West. Though punctuated by humour, Gia Ophelia proves ultimately disquieting—almost exasperating in its steadfast adherence to a conception of femininity four centuries old, its refusal to grant Gia the autonomy and agency that her modern circumstances ostensibly afford her.

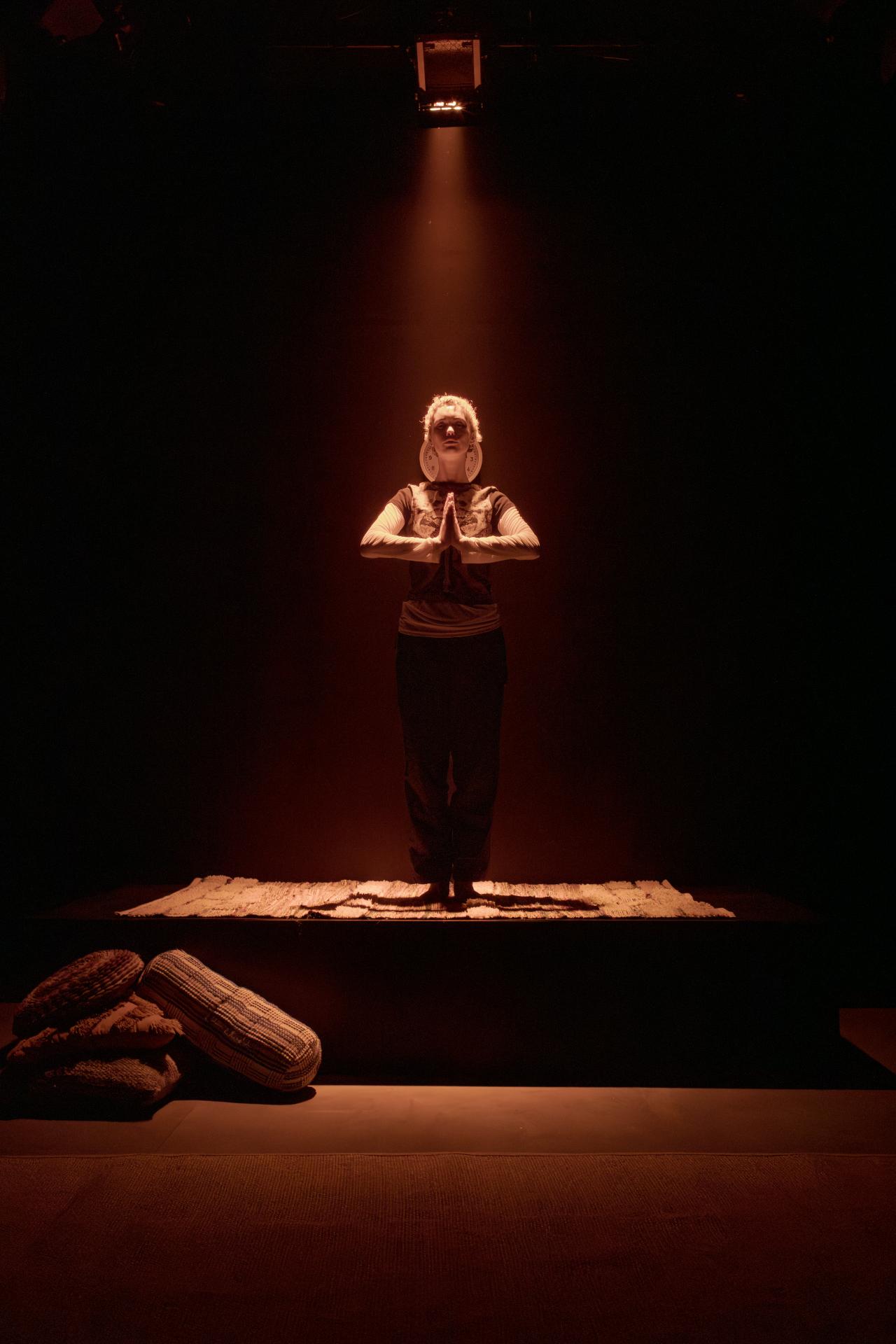

Direction by Jo Bradley proves steadfastly faithful to the spirit of the text, ensuring that the anguish rendered resonates palpably—an unflinching examination of one woman’s conviction of her own failure. Holly Nesbitt’s lighting design confers a superb sense of theatricality, suffusing the stage with wistfulness and melancholy, discovering moments of unexpected beauty in the protagonist’s struggle-worn expressions. Otto Zagala’s sound and music, though occasionally abrupt in their intrusion, are effective additions to the production’s atmospheric intensity.

Annie Stafford delivers a remarkable performance as Gia, navigating with apparent effortlessness from the play’s levities to its despondent core. Whether in moments of lightness or shadow, Stafford proves eminently compelling—quite miraculously preventing the prevailing sadness of Gia Ophelia from estranging its audience.

One might hope that in this modern age, a woman like Gia could locate peace, happiness, and fulfilment beyond the purview of masculine design. Yet the long shadow of hegemonic patriarchy persists, its ancient architecture still shaping the contours of our lives. This is not to suggest, however, that Gia exists merely as its creature. Women have indeed traversed remarkable distance, and the legacy of her forebears has bestowed possibilities of liberation that Shakespeare and his ilk could scarcely have imagined. The past bequeaths its constraints; it also bestows its momentum.