Venue: KXT on Broadway (Ultimo NSW), Nov 15 – 30, 2024

Playwright: Joanna Erskine

Director: Jules Billington

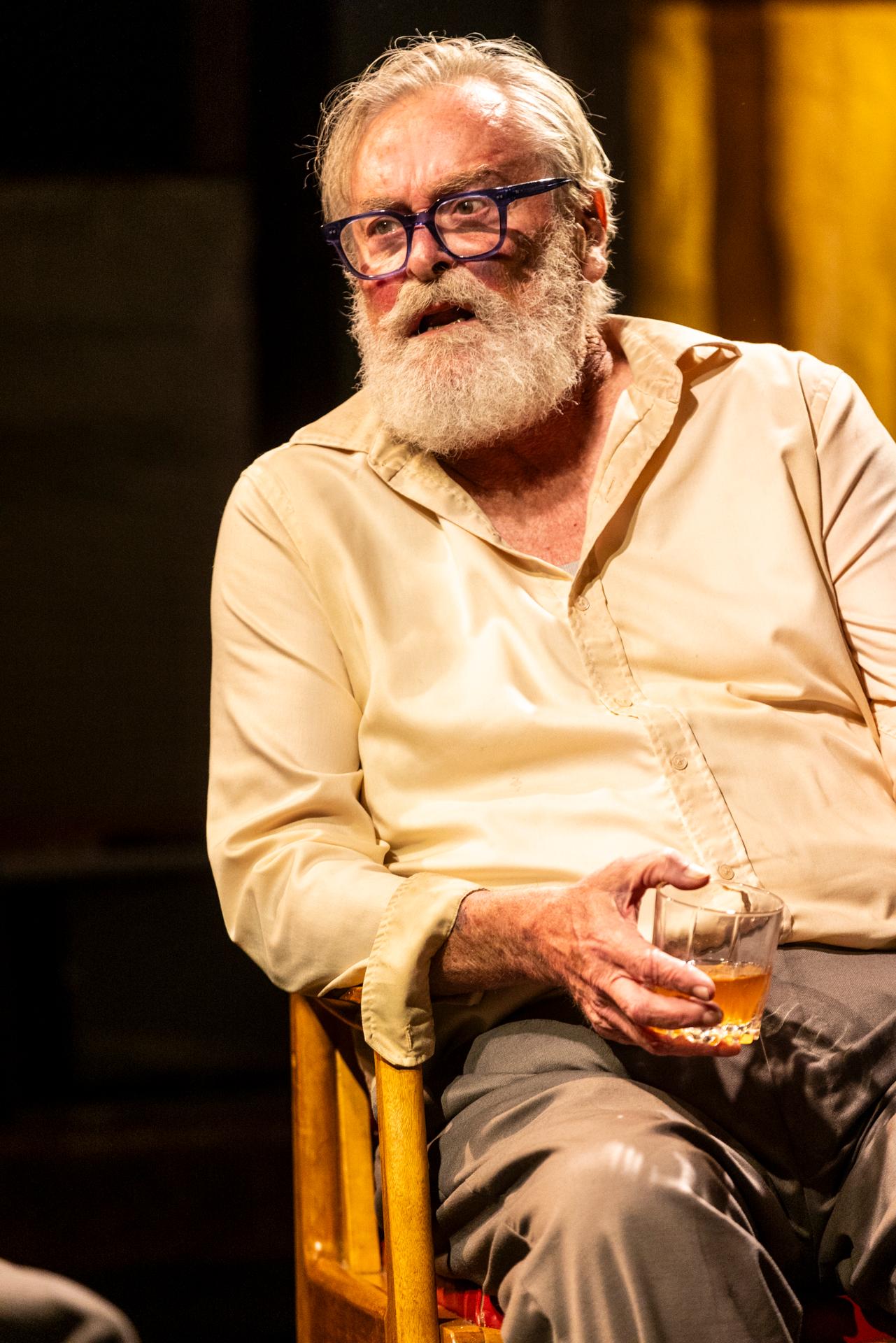

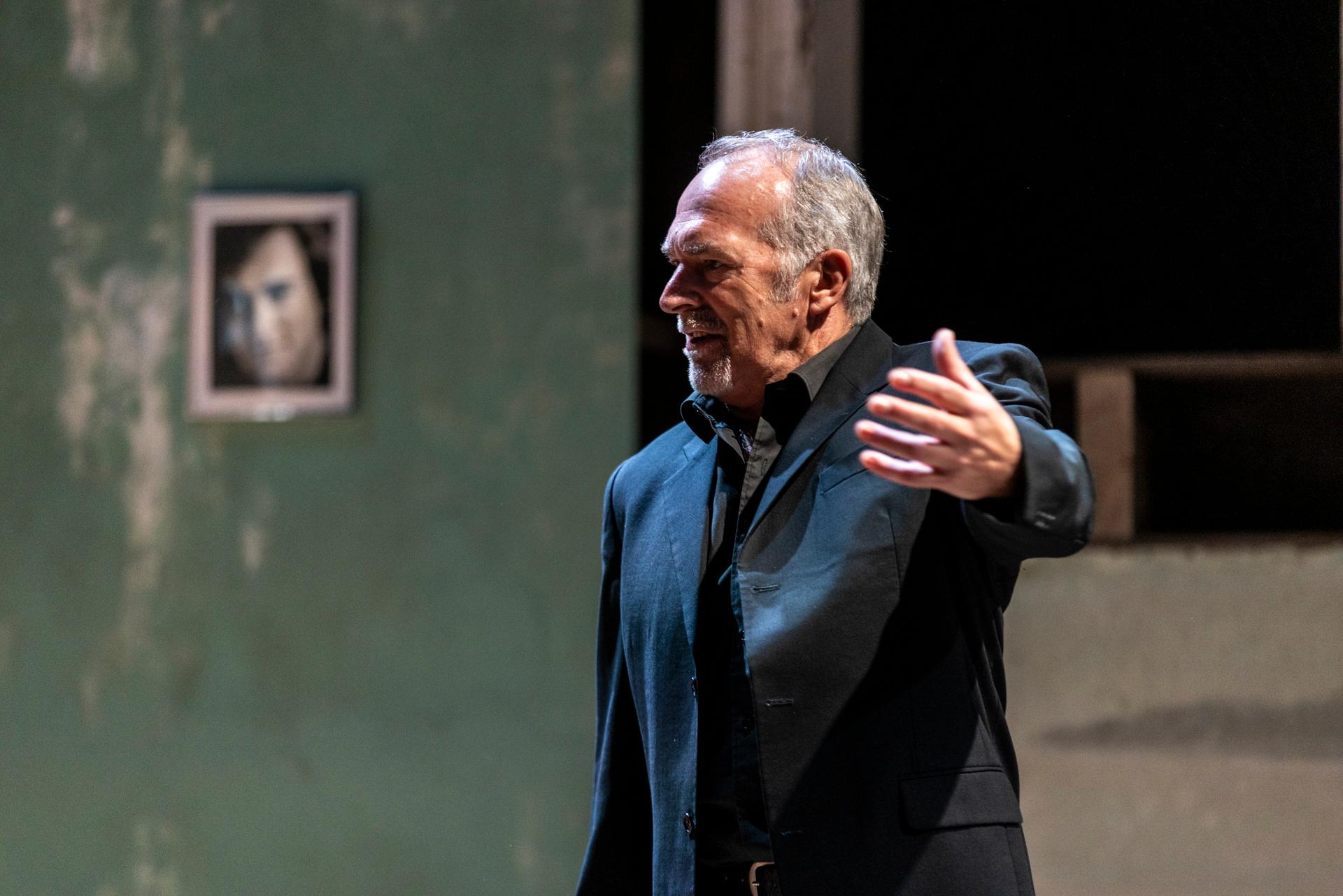

Cast: Ruby Maishman, Tom Matthews, Grace Naoum

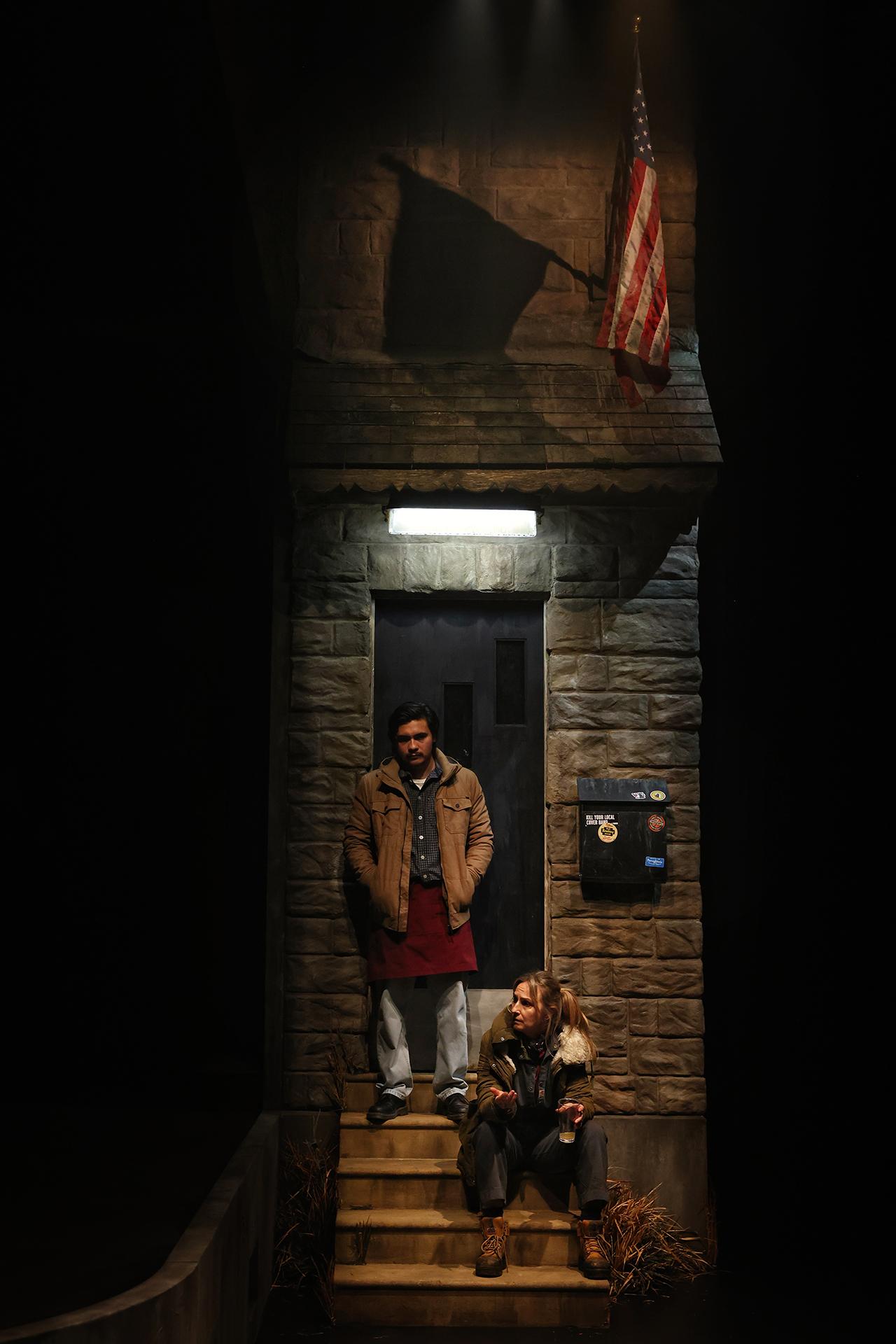

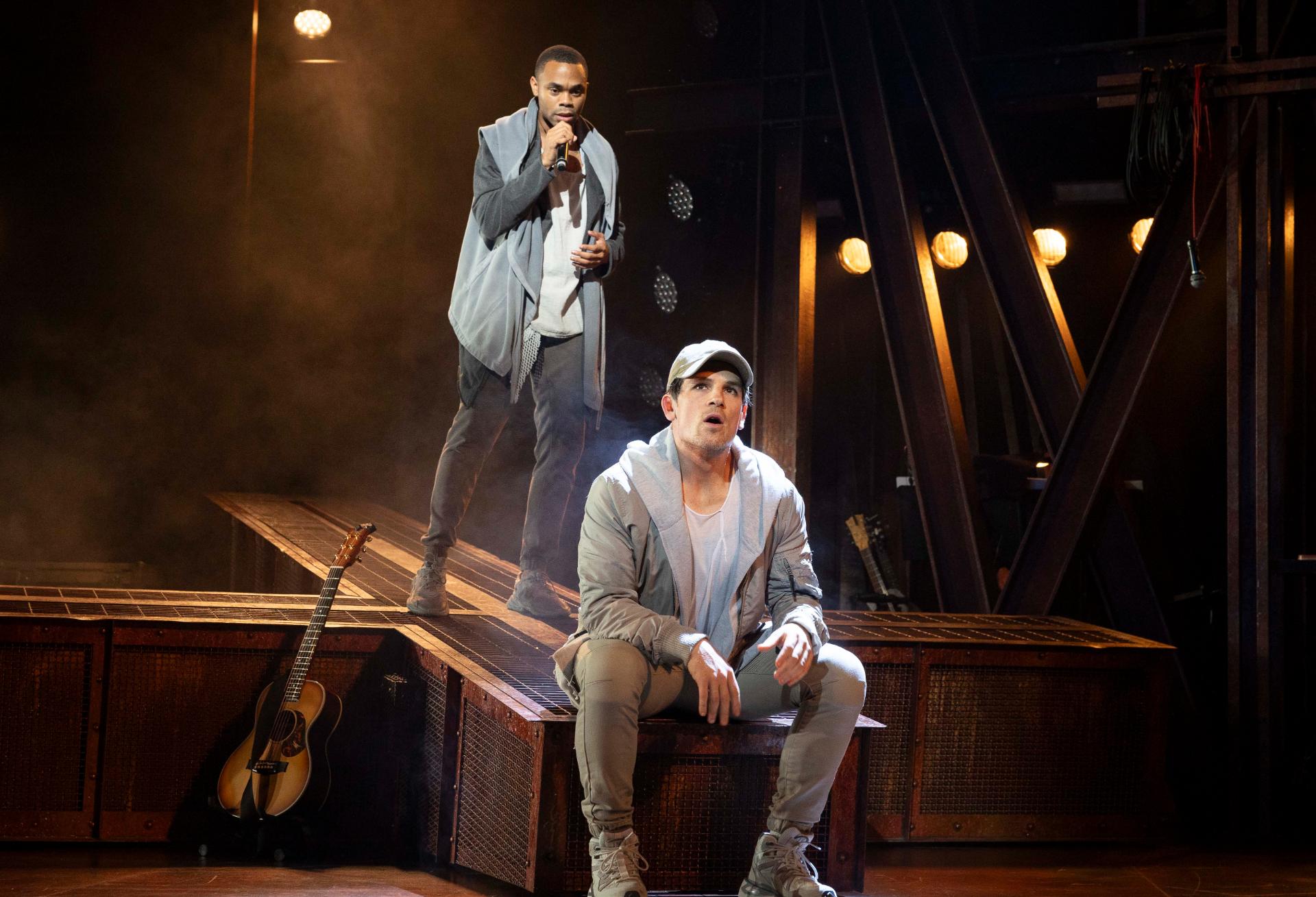

Images by Phil Erbacher

Theatre review

Michael has had a heart transplant, but it seems that he may have inherited more than just Rick’s organ. People Will Think You Don’t Love Me by Joanna Erskine is an intriguing work about consciousness and sentience, particularly how they intersect with human biology. Full of fascinating speculations, Erskine’s play brings into the domestic realm, some of the biggest questions about the mind — where it resides, and how it can transform.

Direction by Jules Billington brings great focus to these intimate explorations, highly compelling with their ability to make believable, these often outlandish conjectures. There is however a diminishment of dramatic intensity, in concluding portions of the show where we are poised in expectation of an escalation. Its cerebral quality though, does fortunately persist to the end, for a satisfying experience that is likely to remain with viewers long after the curtain call.

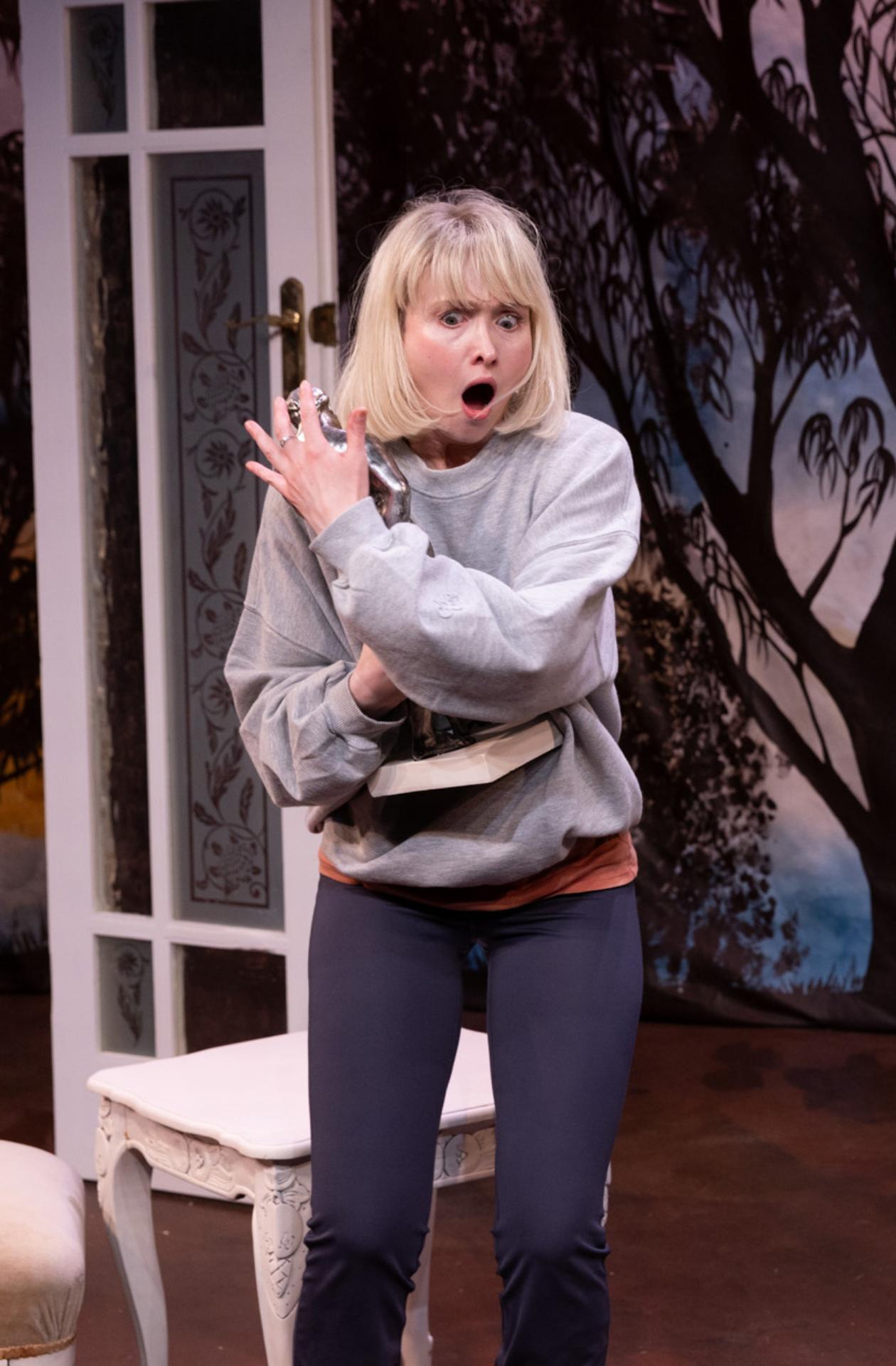

Sam Wylie’s production design is a visually pleasing amalgamation of locations, successful at representing the various settings, and accurate with costuming that illustrates the regular Sydney folk we encounter in the story. Wylie’s lights operate well to encourage our sentimental responses, but can afford to be more ambitious in segments that veer into surreal territory. Sounds and music by Clare Hennessy are extremely delicate, memorable for their efficacy at bringing subtle tension, to these scenes of mounting discord.

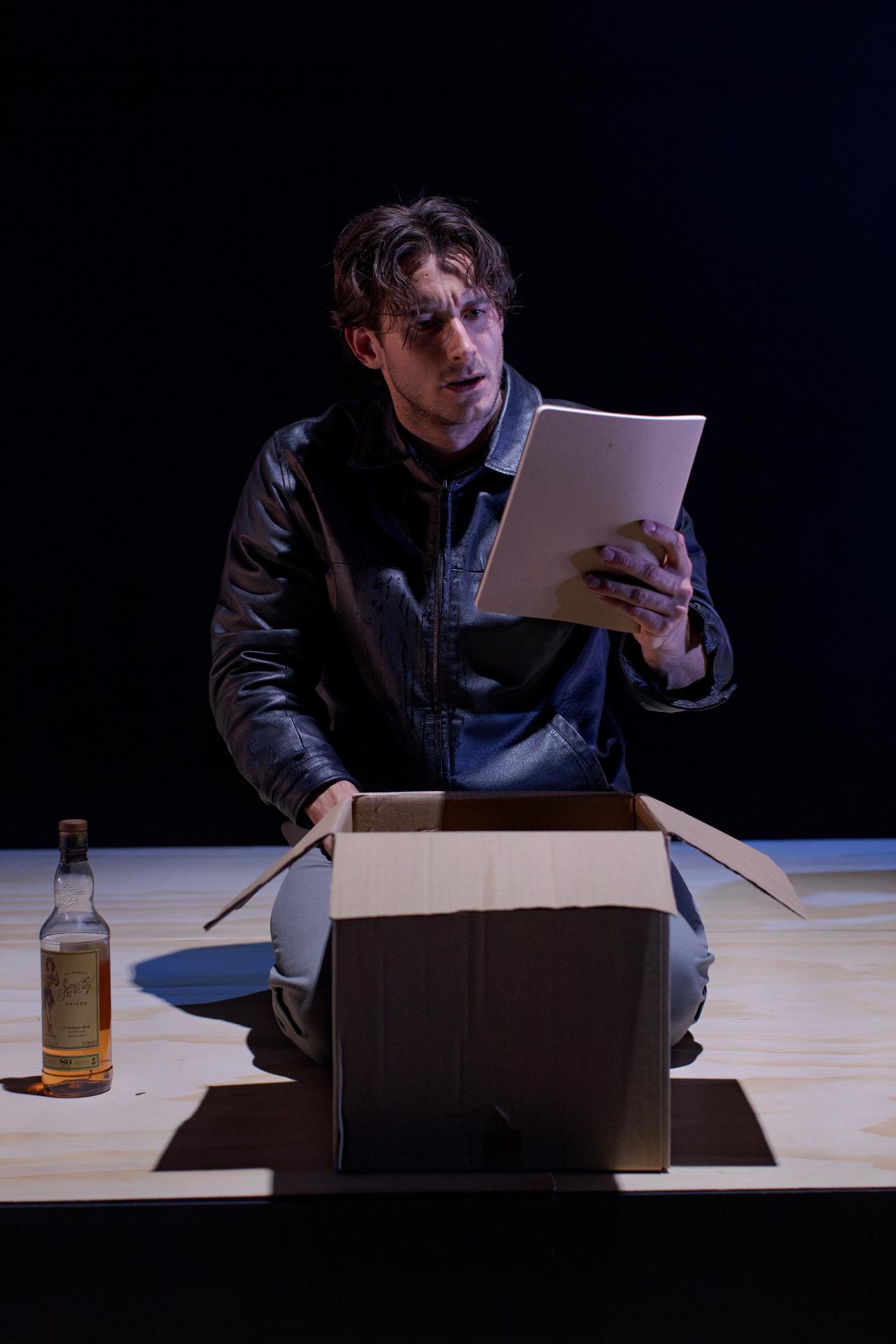

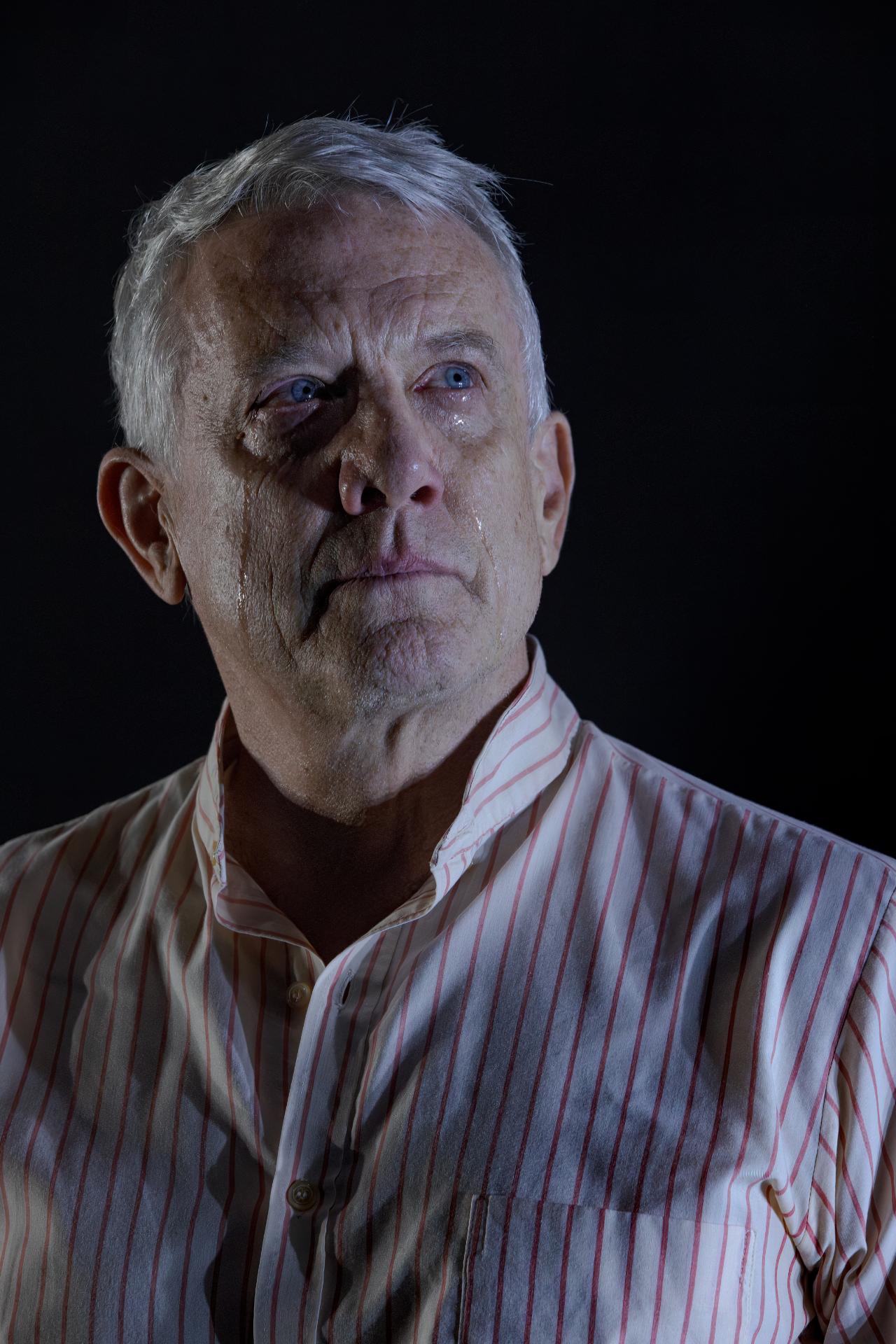

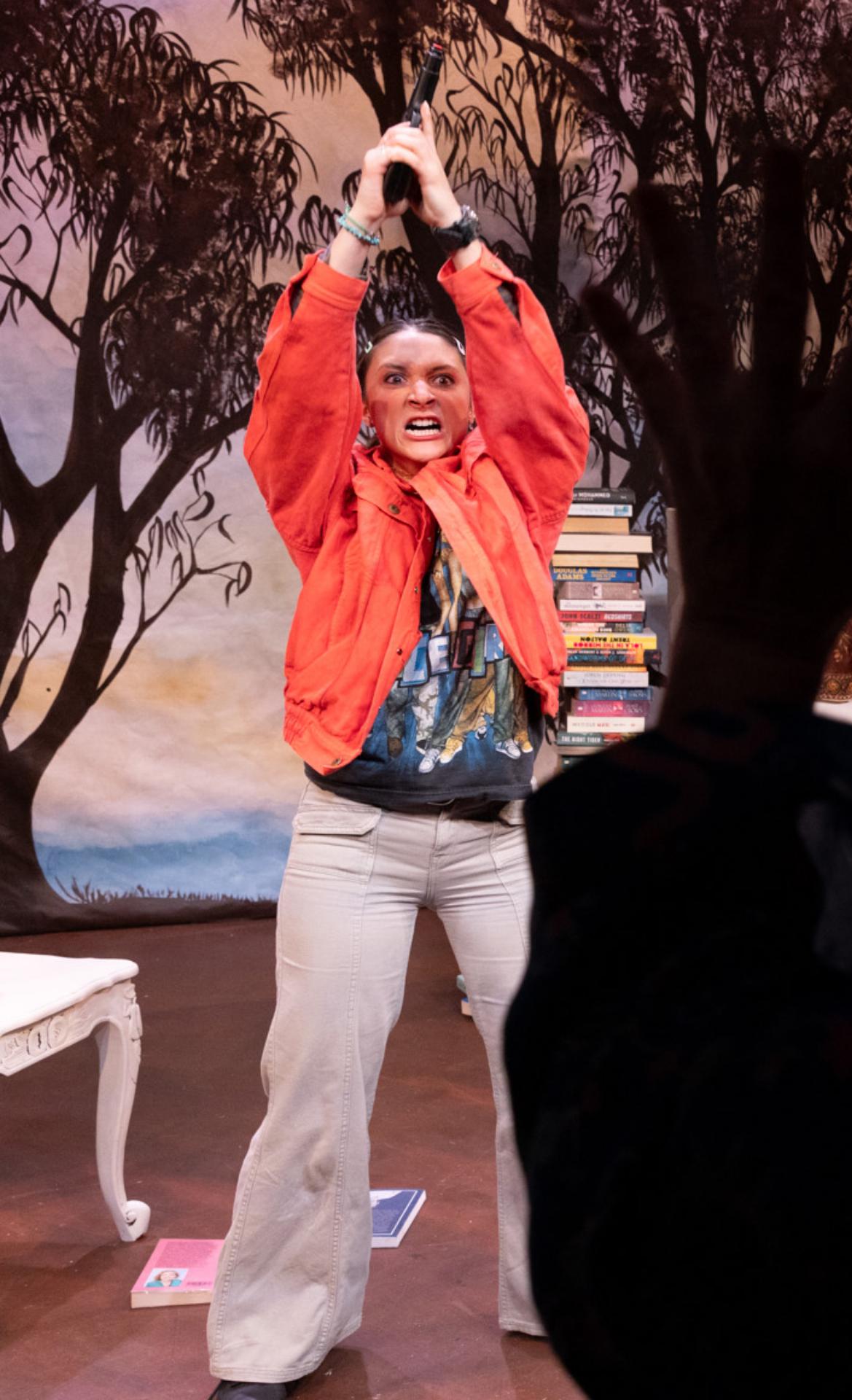

A strong cast of three presents People Will Think You Don’t Love Me with admirable deliberation and detail. Tom Matthews brings a valuable naturalism to the role of Michael, to keep us invested and persuaded of the play’s extravagant musings. Playing Michael’s wife Elizabeth, is Grace Naoum who introduces urgency whenever required, and is always convincing when portraying the anxiety navigated by someone under constant stress. The organ donor’s partner Tomasina is depicted by Ruby Maishman with a wonderful idiosyncrasy that makes her character feel familiar and realistic. The compelling chemistry between actors is a marvellous feature, especially when unexpected humour arises, in this otherwise quite sombre staging.

In the enactment of our capitalistic lives, there is often insufficient care and respect for the bodies we inhabit. The heart, soul and mind are often relegated to something almost abstract, even though we know them to be absolutely central. We often fall into thinking ourselves as somewhat ephemeral, whilst simultaneously mistreating our corporeality, endlessly making bodies serve their capitalistic purposes of productivity, and ignoring their more esoteric capacities. Love and the human spirit are real, and they could very well be living not in the ether, but in all of our blood, skin, flesh and bones.

www.kingsxtheatre.com | www.facebook.com/littletrojantheatre