Venue: KXT on Broadway (Ultimo NSW), May 24 – Jun 8, 2024

Playwright: Shayne

Director: Kim Hardwick

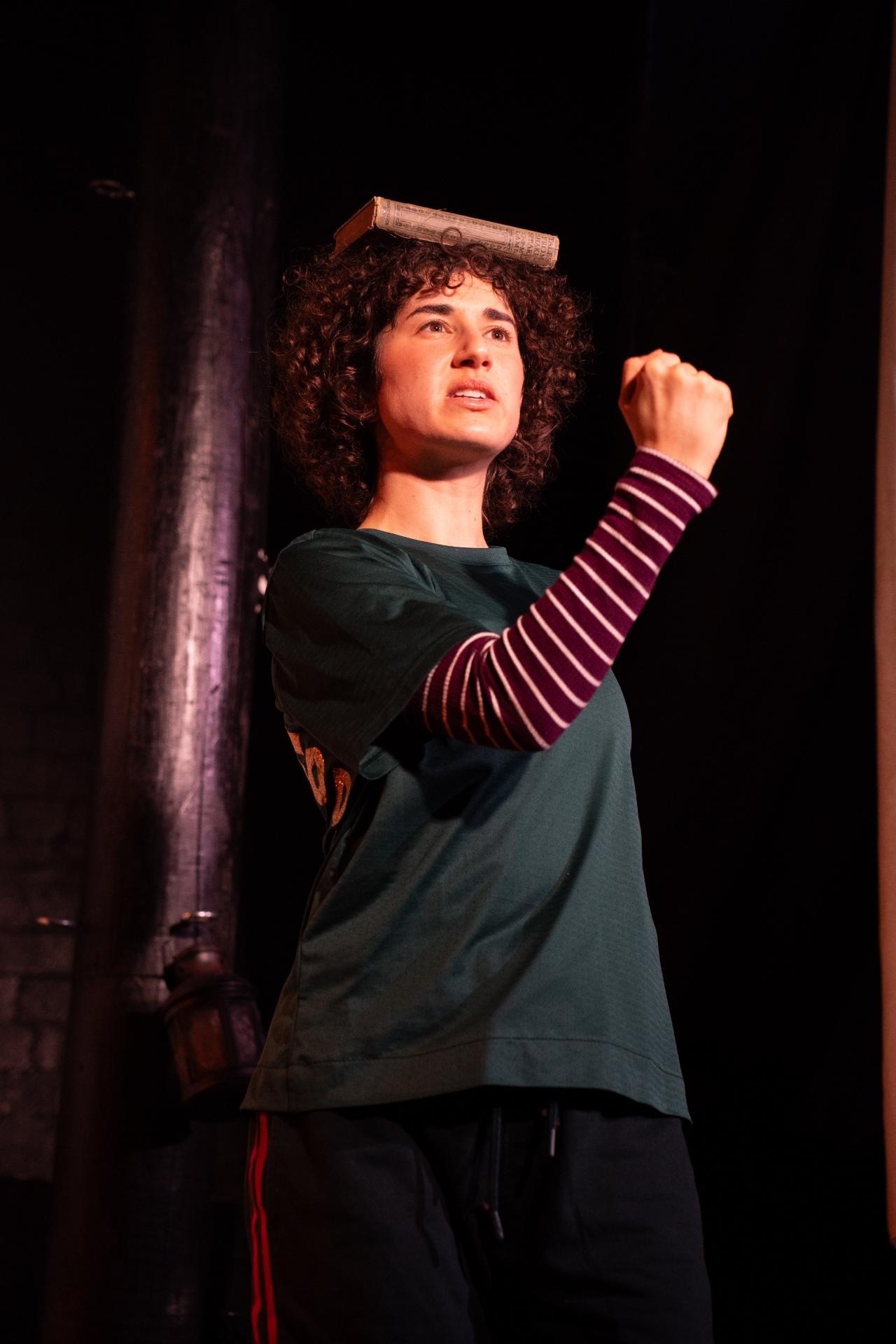

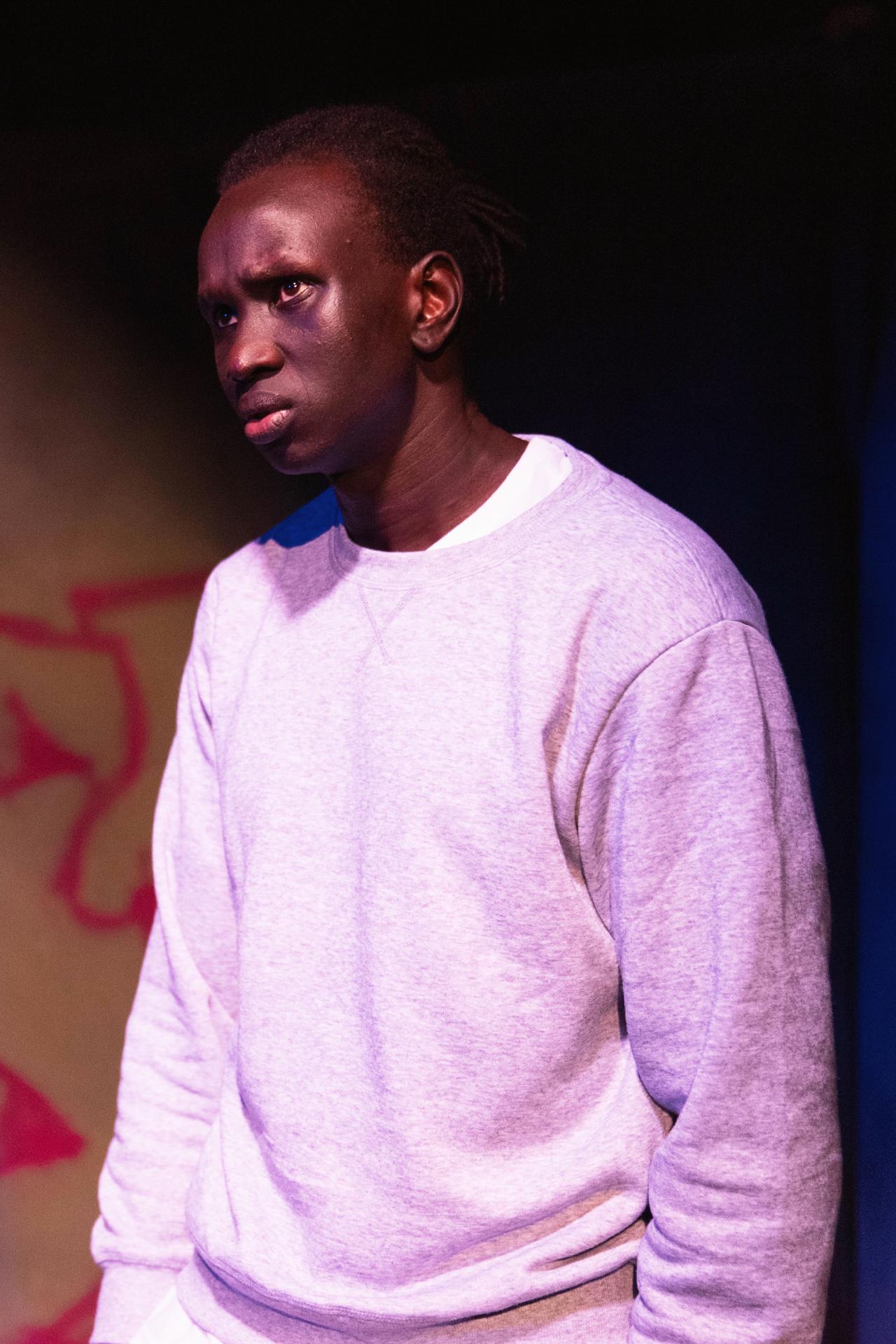

Cast: Laneikka Denne, Jack Patten

Images by Clare Hawley

Theatre review

One sibling has Contamination Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, and the other has alcohol addiction. There is an admirable closeness between the two, but neither is able to ameliorate their individual problems, so maybe bringing a pet dog into the fold, would help things get better. In this extraordinary two-hander by playwright Shayne, with the simple title of Dog, dialogue is sparse and almost futile, as characters skirt around issues that are too hard to name. All that is important in the play, is conveyed between the lines, and as subtexts, in a work of art that relies thoroughly on the faculties of the theatrical form.

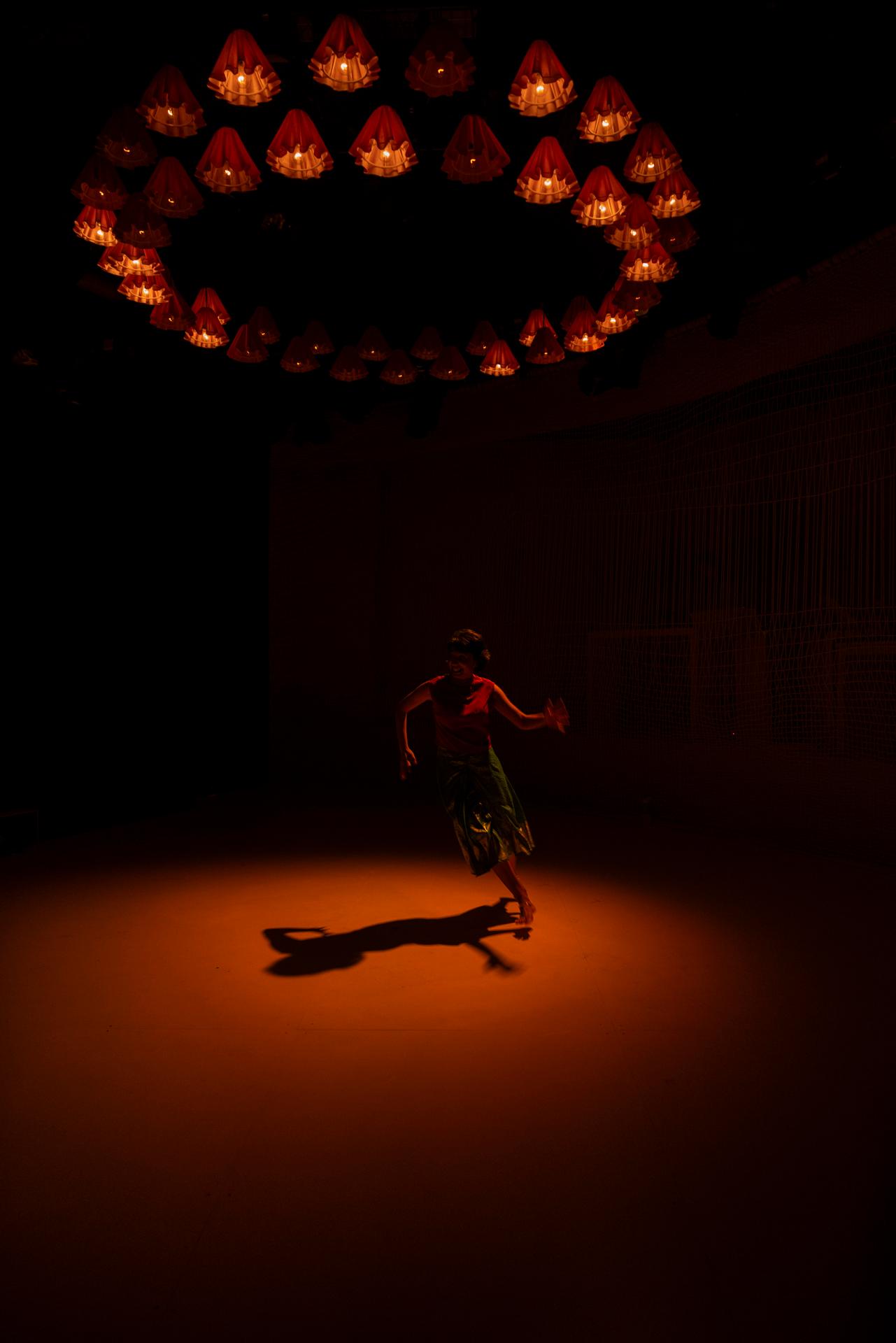

Dog requires our experience to be an intimate one, to feel as though we are immersed in the siblings’ world of unspeakable truths. Director Kim Hardwick’s ability to make us feel as though part of the action, allows us to read into the many nuances and complexities of the characters’ lives, so that we may form understandings of what they cannot articulate. Hardwick’s detailed manipulations of all that we see and hear, makes for a mesmerising ninety minutes, almost Australian Gothic in style and tone, during which we find ourselves hopelessly invested, in the struggles of these young people’s daily realities.

Production design by Ruby Jenkins takes us convincingly away from our inner city bourgeois existence, to somewhere decidedly more grounded and raw. With its unmistakeable coldness, lights by Frankie Clarke depict a certain unrelenting brutality, that the siblings have to face. Aisling Bermingham’s sounds are marvellously intricate, and exceptional in their effectiveness as a mechanism for storytelling, in a show that seeks to communicate in ways other than words.

Actor Laneikka Denne sets the scene with the most vulnerable expressions, of a person in the throes of uncontrollable urges, completely powerless against their mental illness. Denne’s depictions of pain, and of battling with pain, are persuasive and with a generous sense of empathy, that encourages us to examine these difficult situations with a corresponding compassion. Jack Patten’s portrayal of a man grappling with a severe drinking problem, astonishes with its realism. The danger that he poses to others and to himself, is a tension that suffuses the atmosphere, and that provides for the staging, its delicious sense of drama.

All humans are imperfect, but some of our dysfunctions are of an intensity, that they simply cannot be regarded as normal parts of any being. There is no real need for anyone to conform to social codes or normative behaviours, but when something becomes a persistent hindrance to a person’s flourishing, help must be made available and accessible. It is up to the siblings in Dog to decide for themselves, when enough is enough. When they finally open up to support and treatment, it is imperative that all the tools they need, are ready and waiting.