Venue: KXT on Broadway (Ultimo NSW), Aug 25 – Sep 9, 2023

Playwright: Eric Jiang

Director: Sammy Jing

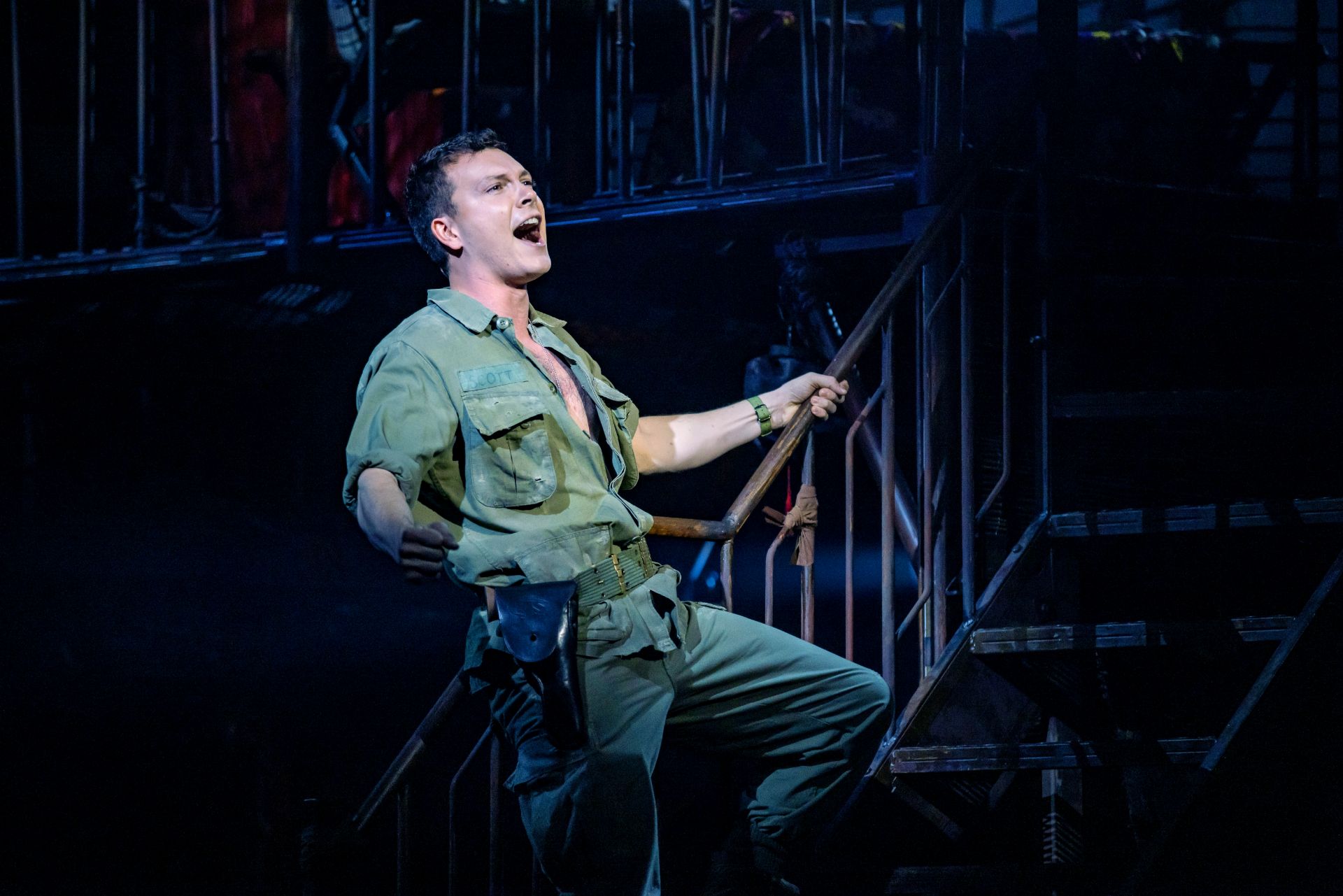

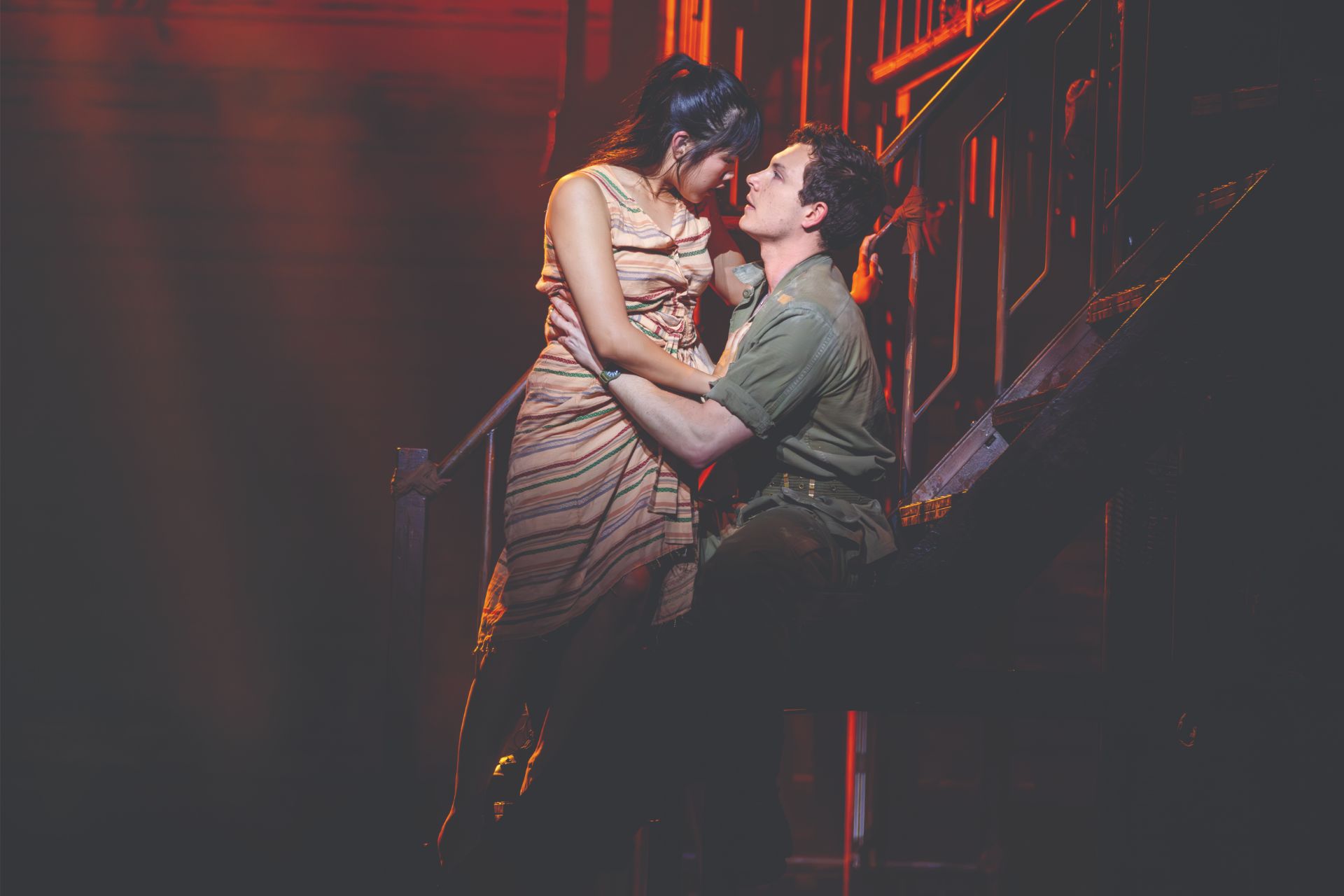

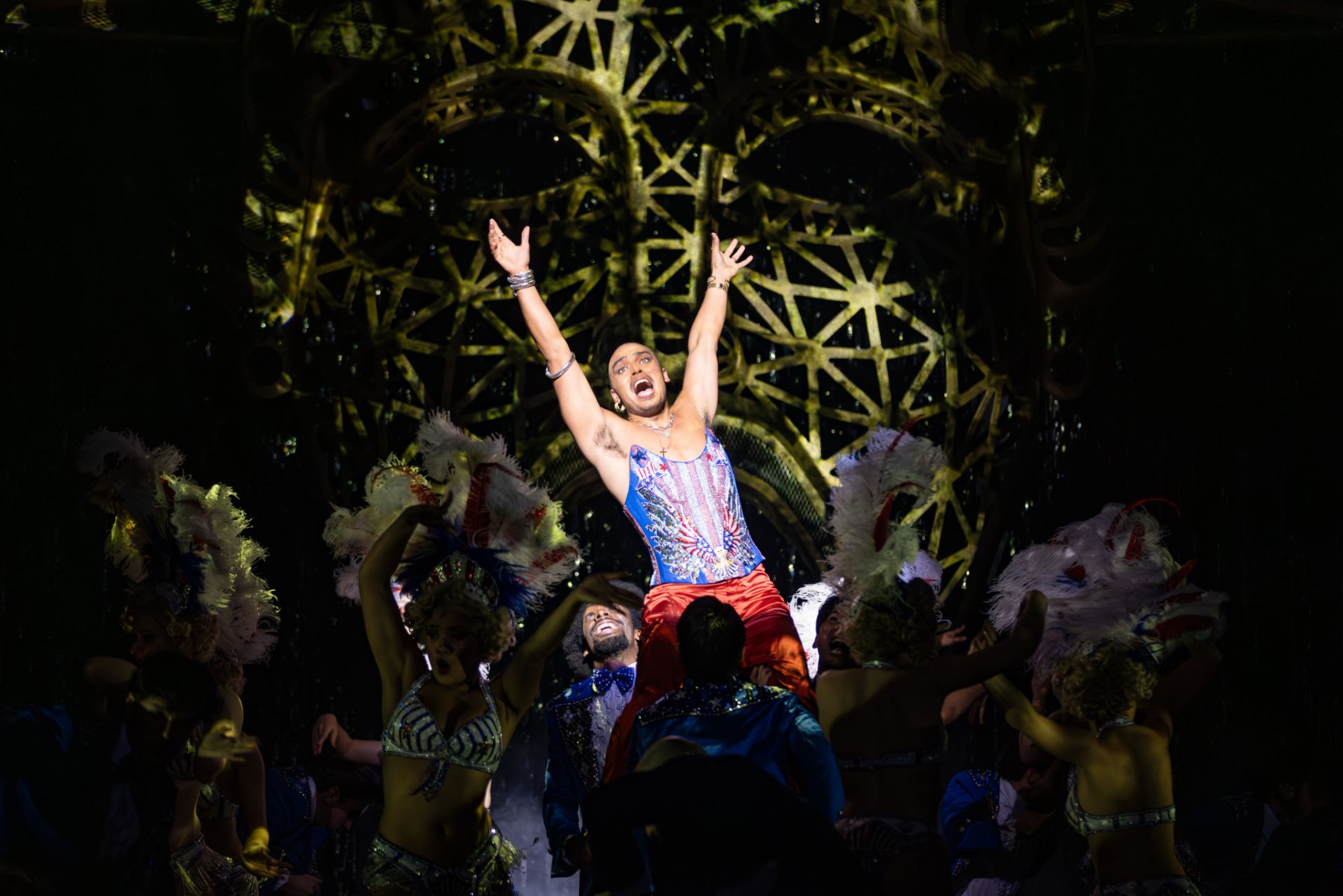

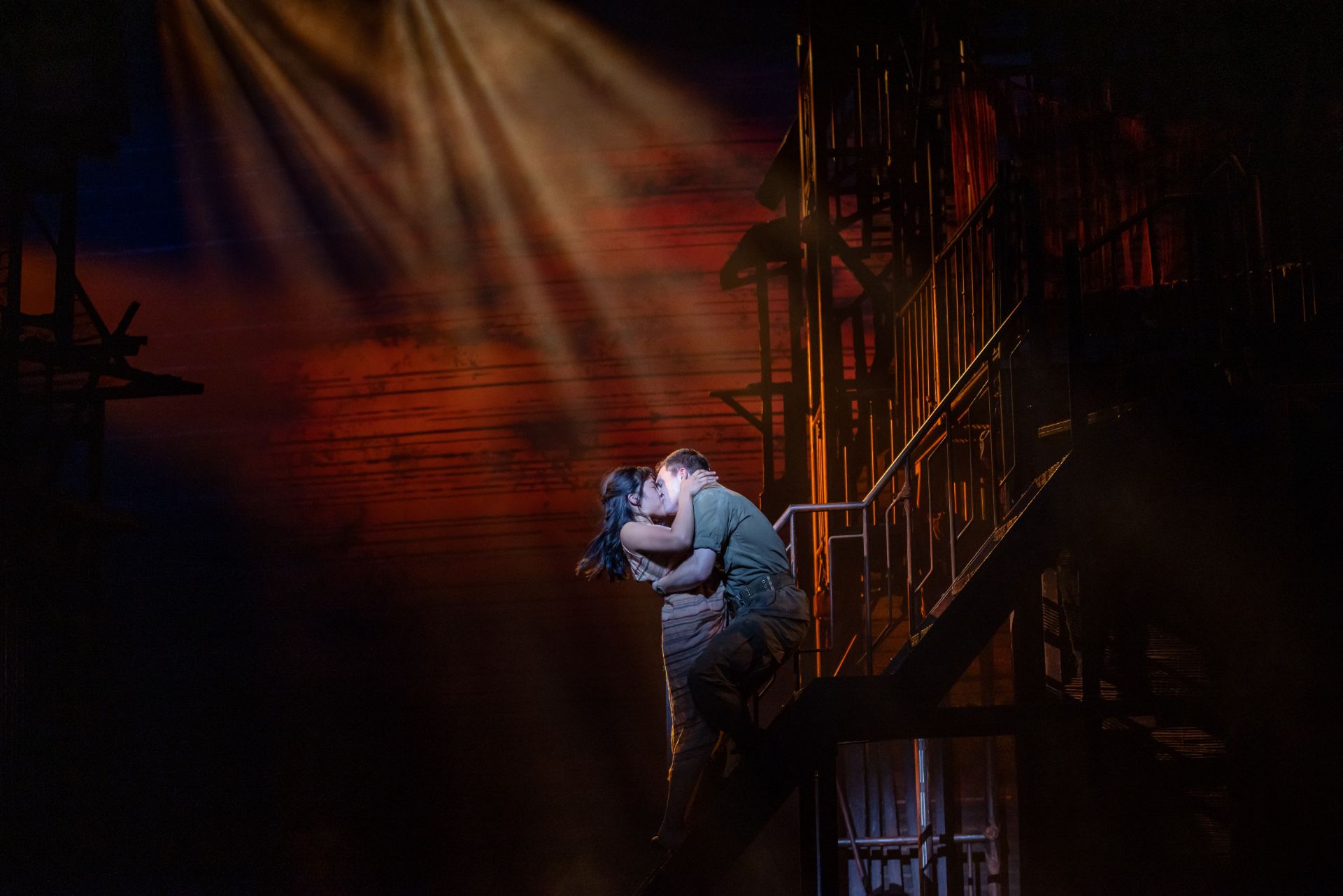

Cast: Richard Wu, Luke Visentin, Joseph Raboy

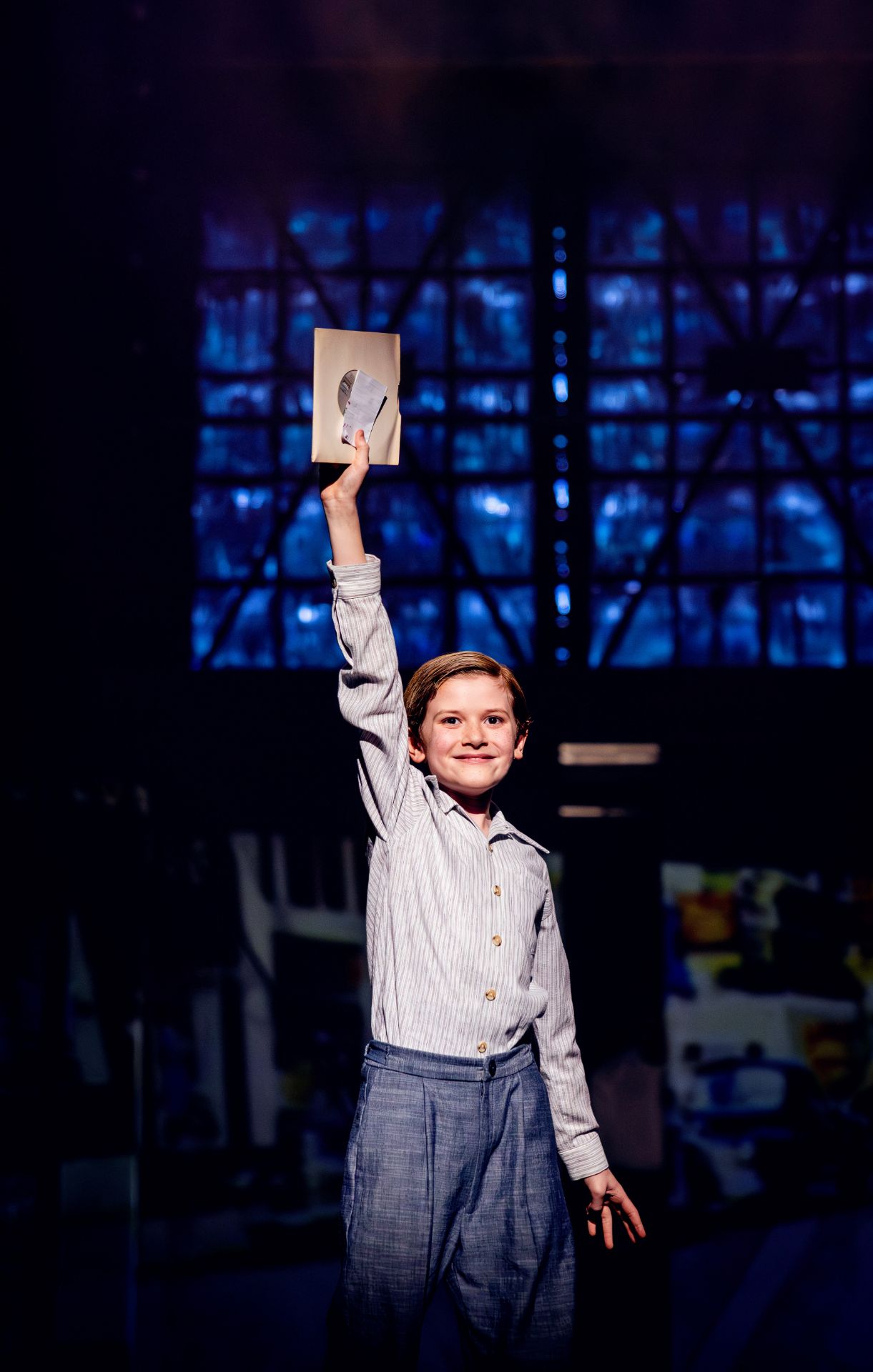

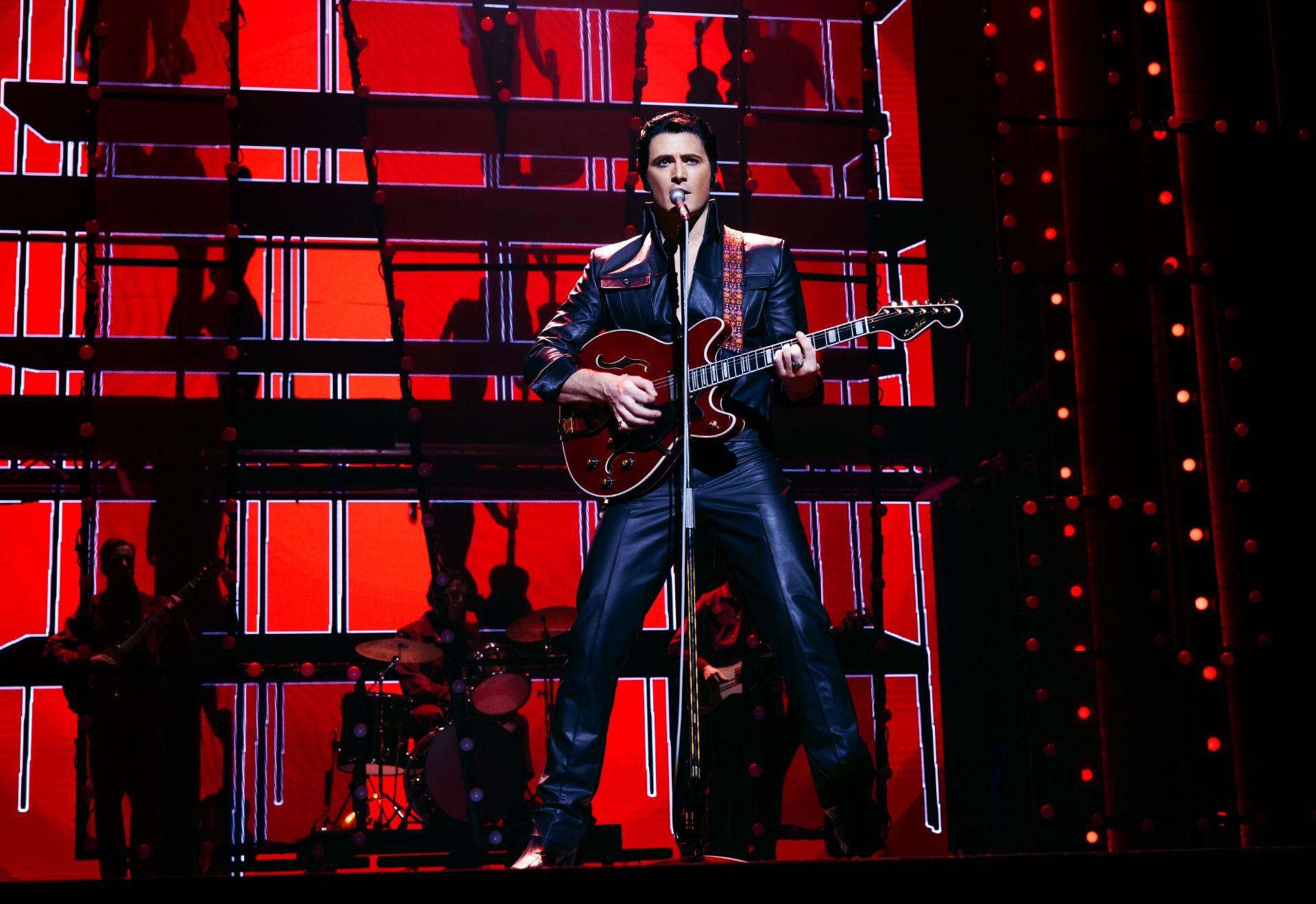

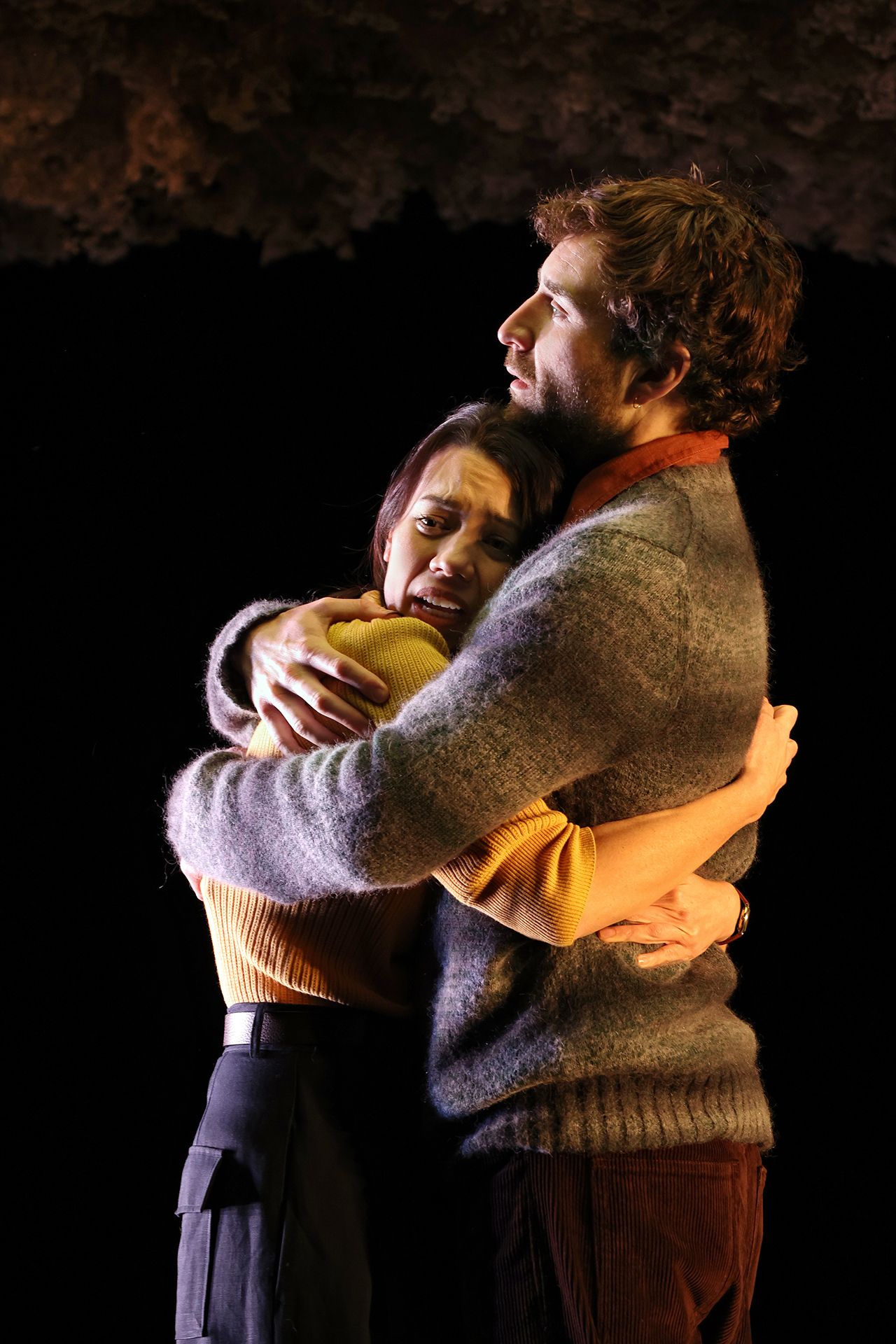

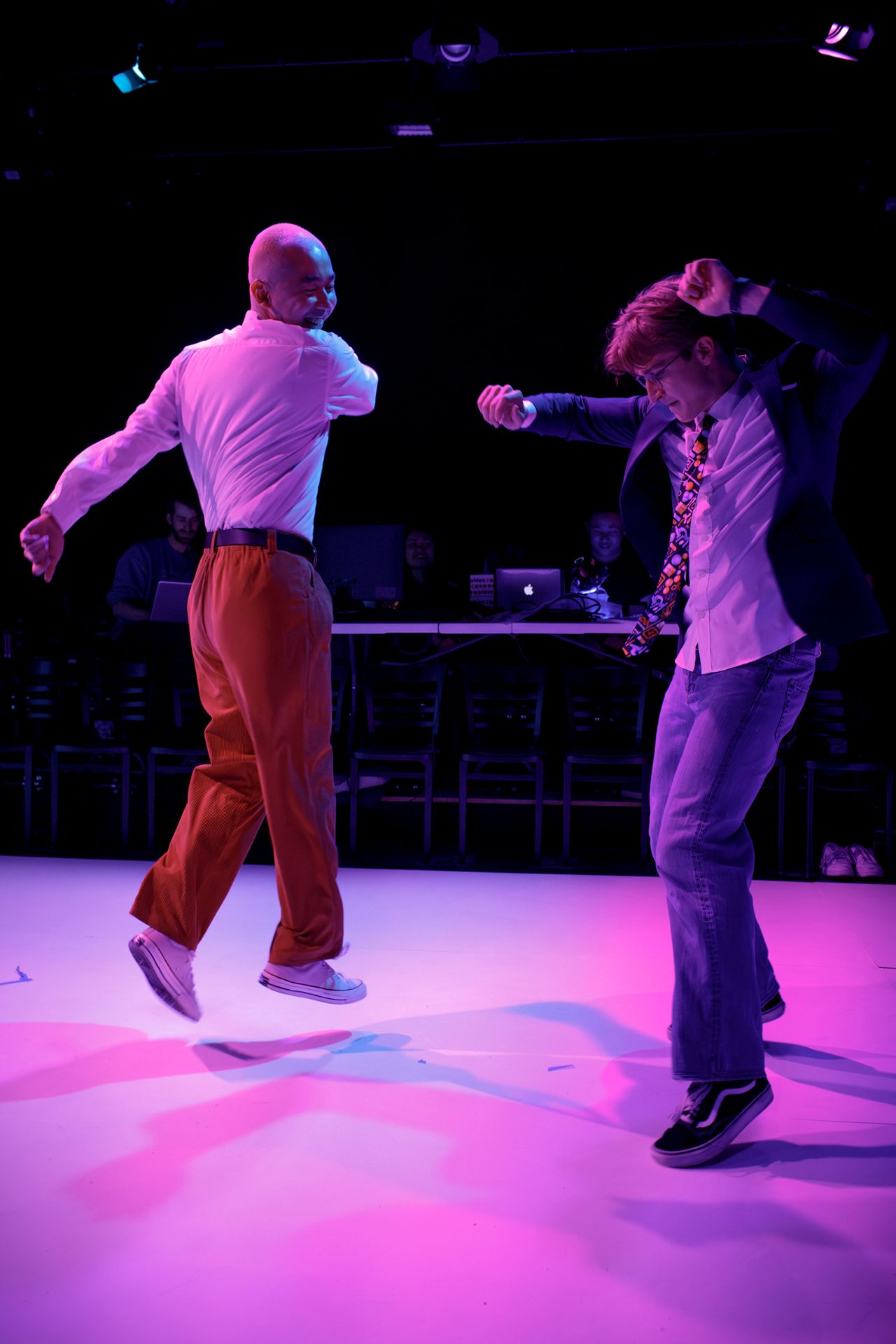

Images by Phil Erbacher

Theatre review

Xavier is young and queer, so it comes as no surprise, that he should choose to reject traditional definitions of love and relationships, even if he does feel very attracted to Sebastian. In Eric Jiang’s Rhomboid, we see the couple trying to come to terms with the nature of their connection, in ways that defy the strict parameters that usually dictate how we perceive matters of the heart. What the two feel for each other is real, in a world that often places false or arbitrary expectations, on how we regard romantic unions.

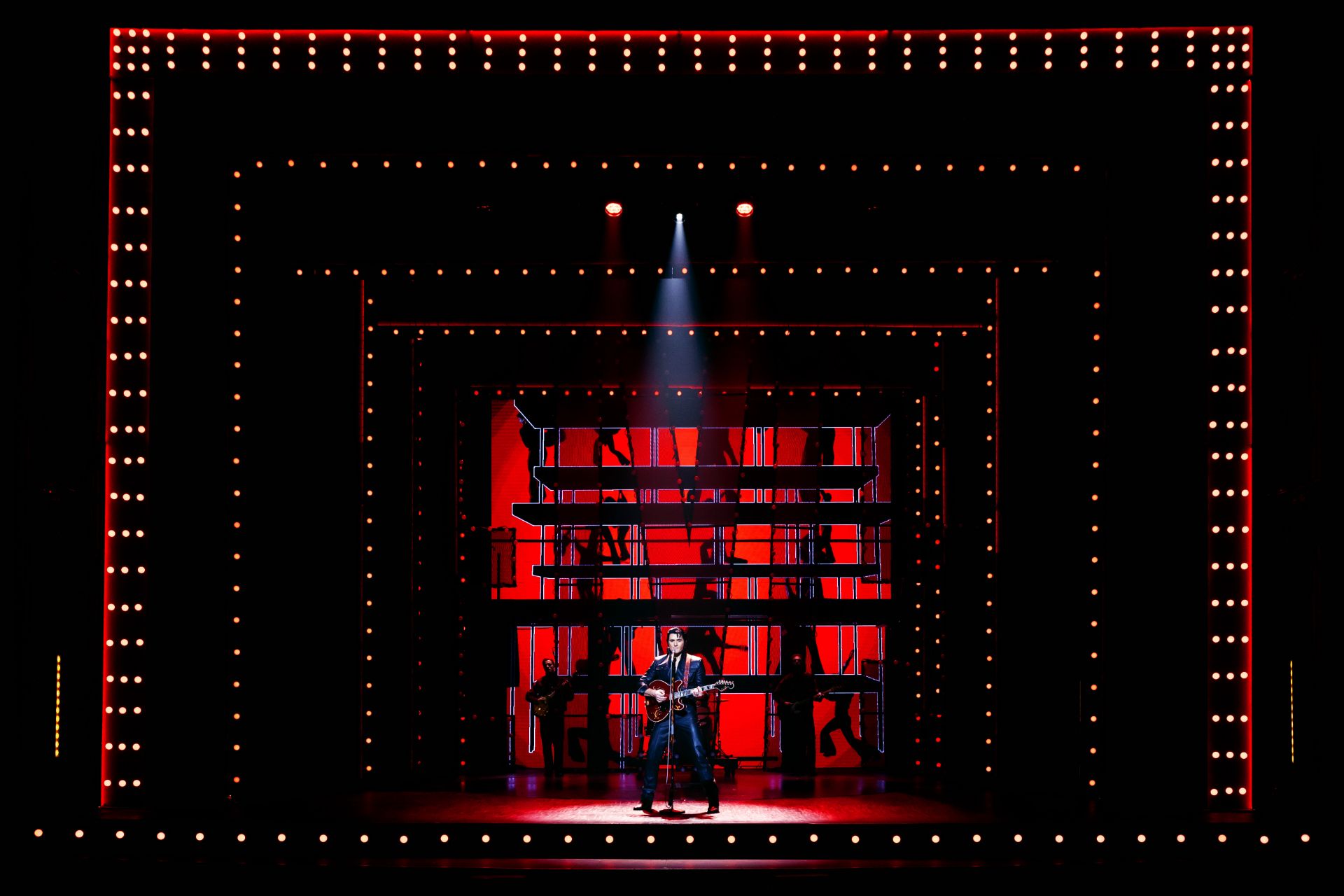

The unique whimsy of Jiang’s writing is thoroughly enchanting, with an inherently arresting theatricality that director Sammy Jing explores with admirable exuberance, for a show intent on saying something valuable, whilst finding ways to present itself in fresh and artistic ways. Rhomboid is wonderfully quirky with its humour, if slightly slow in pacing. There is a pureness in thought and purpose that really shines, for a work memorable for both its style and meaning.

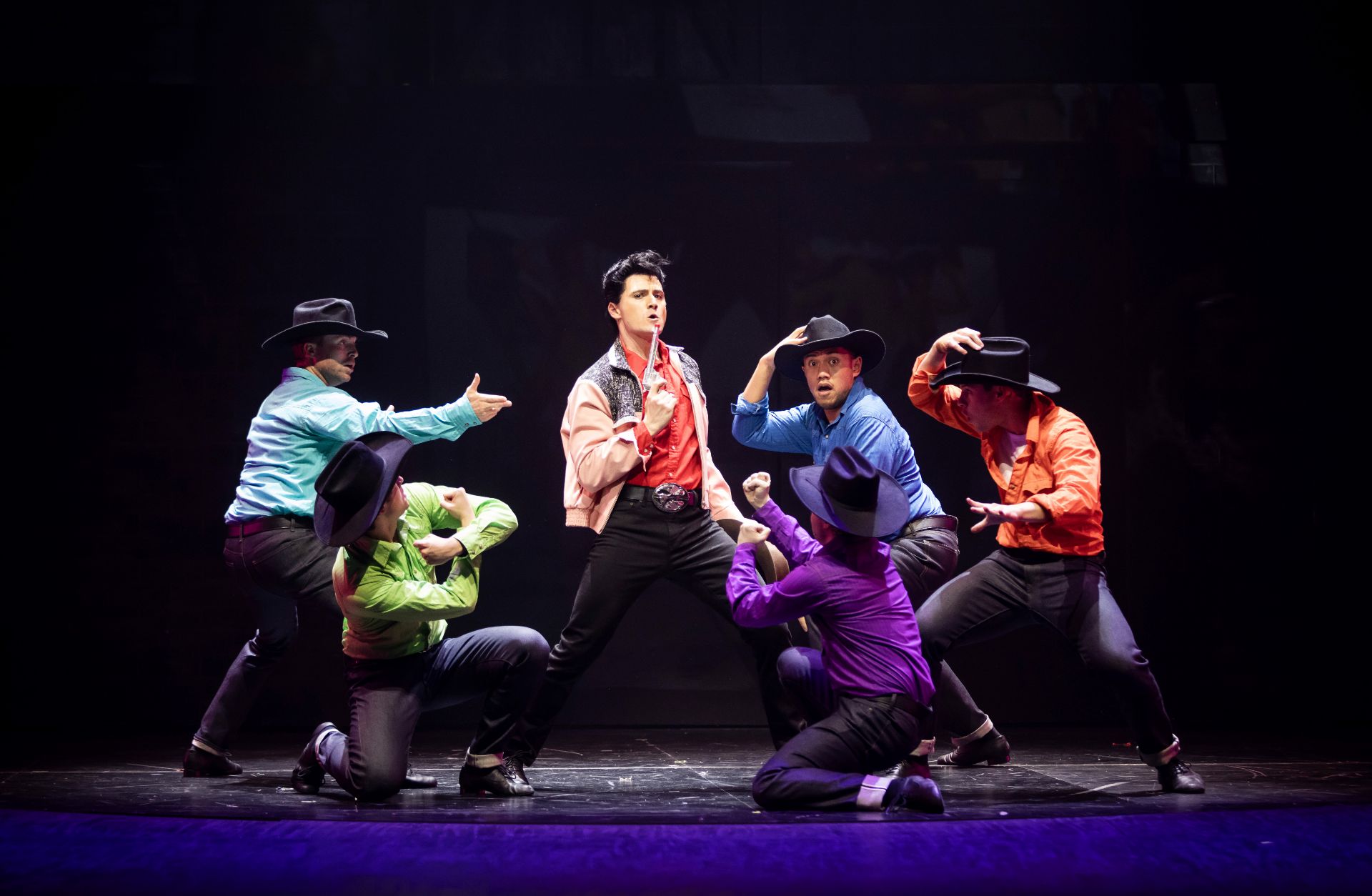

Set design by Paris Bell is simple but attractive, although its construction could benefit from greater finesse. Lily Mateljan’s costumes are very much of the times, pleasingly colourful in their depictions of the contemporary queer man. Lights by Catherine Mai are experimental and considered, beautiful in the ways they gently coax our minds into surprisingly generous spaces. Christine Pan’s sound and music are thoroughly rendered, to ensure that the experience is a rich one.

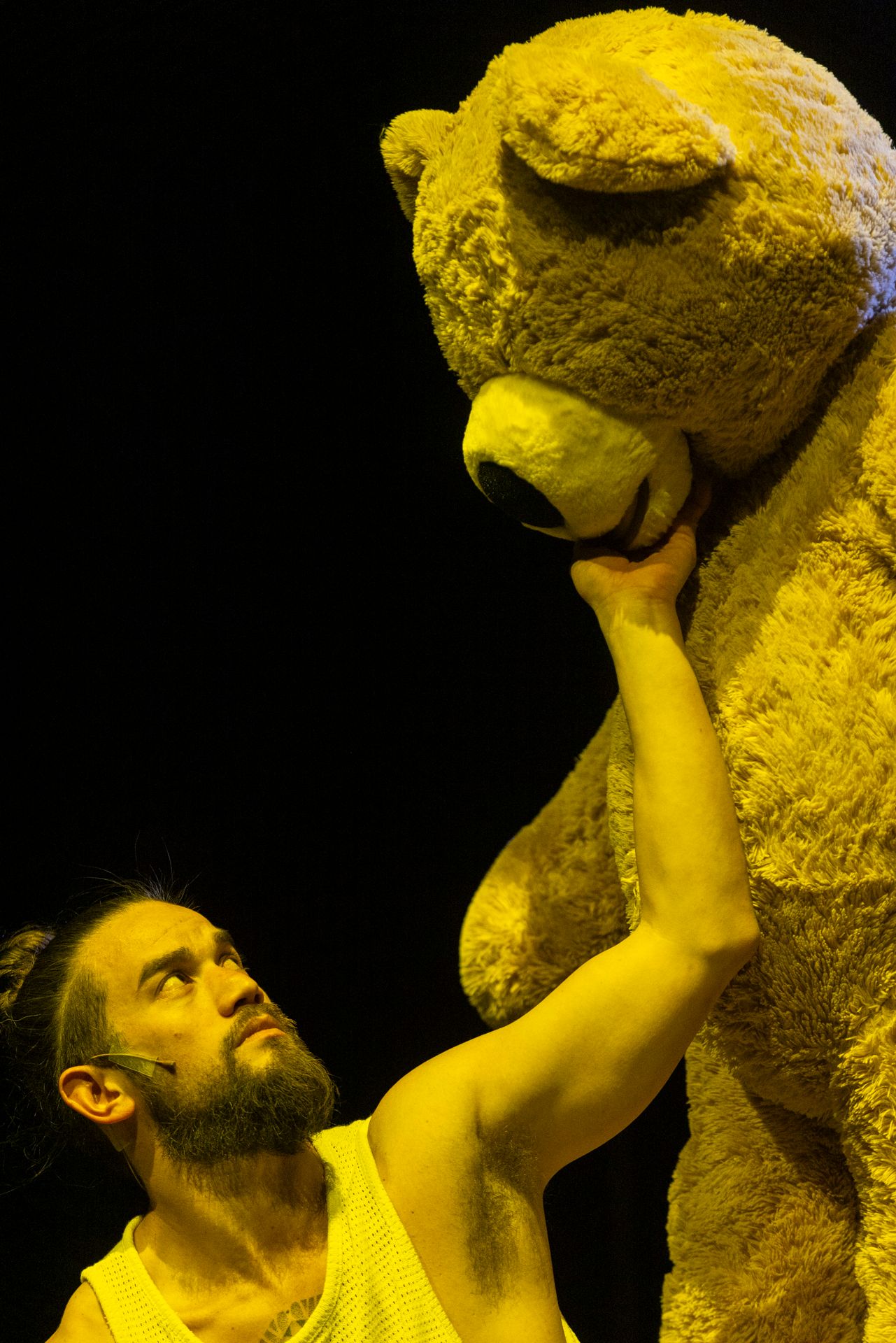

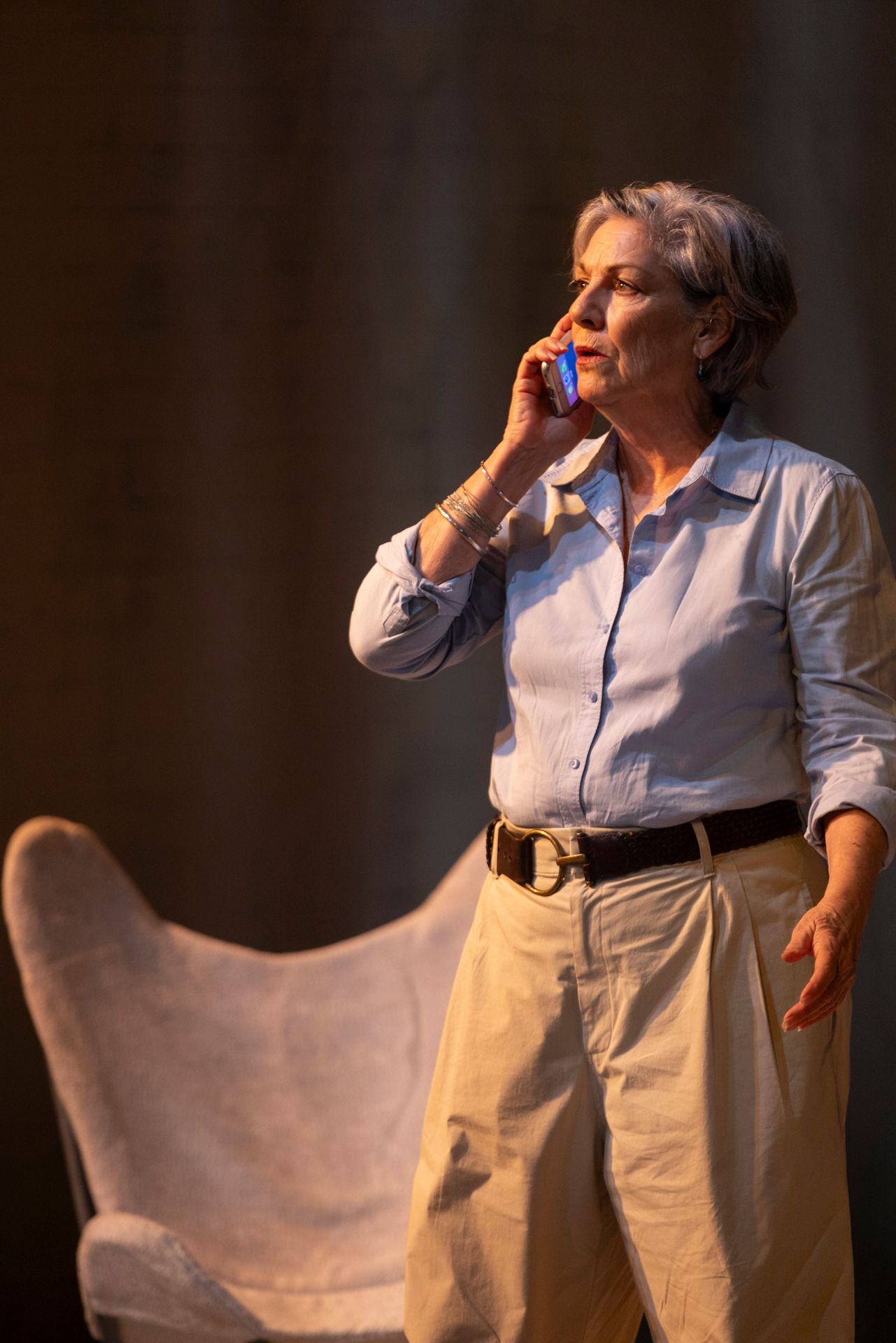

Actor Richard Wu is extremely charming as Xavier, and marvellously compelling as he makes the case for new ways to understand love in the modern age. Luke Visentin is both funny and earnest as Sebastian, with an easy presence that allows the character to always be convincing. Playing the dual roles of Felix and Lachy, is Joseph Raboy who brings an excellent camp sensibility to the show, effervescent but measuredly so.

It is strange when queer people make straight choices, when we contort our beings to fit moulds that were always made to exclude. Rhomboid represents a joyful resistance of definitions and prescriptions, the ones that have failed us time and time again. Queer people understand freedom in a deep way. We understand that the possession and control of others, is the very antithesis of love. Watching Xavier and Sebastian making their own rules, one is reminded of the liberation that will always be worth fighting for.