Venue: KXT on Broadway (Ultimo NSW), Jun 23 – Jul 8, 2023

Playwright: Jacob Parker

Director: Sophia Bryant

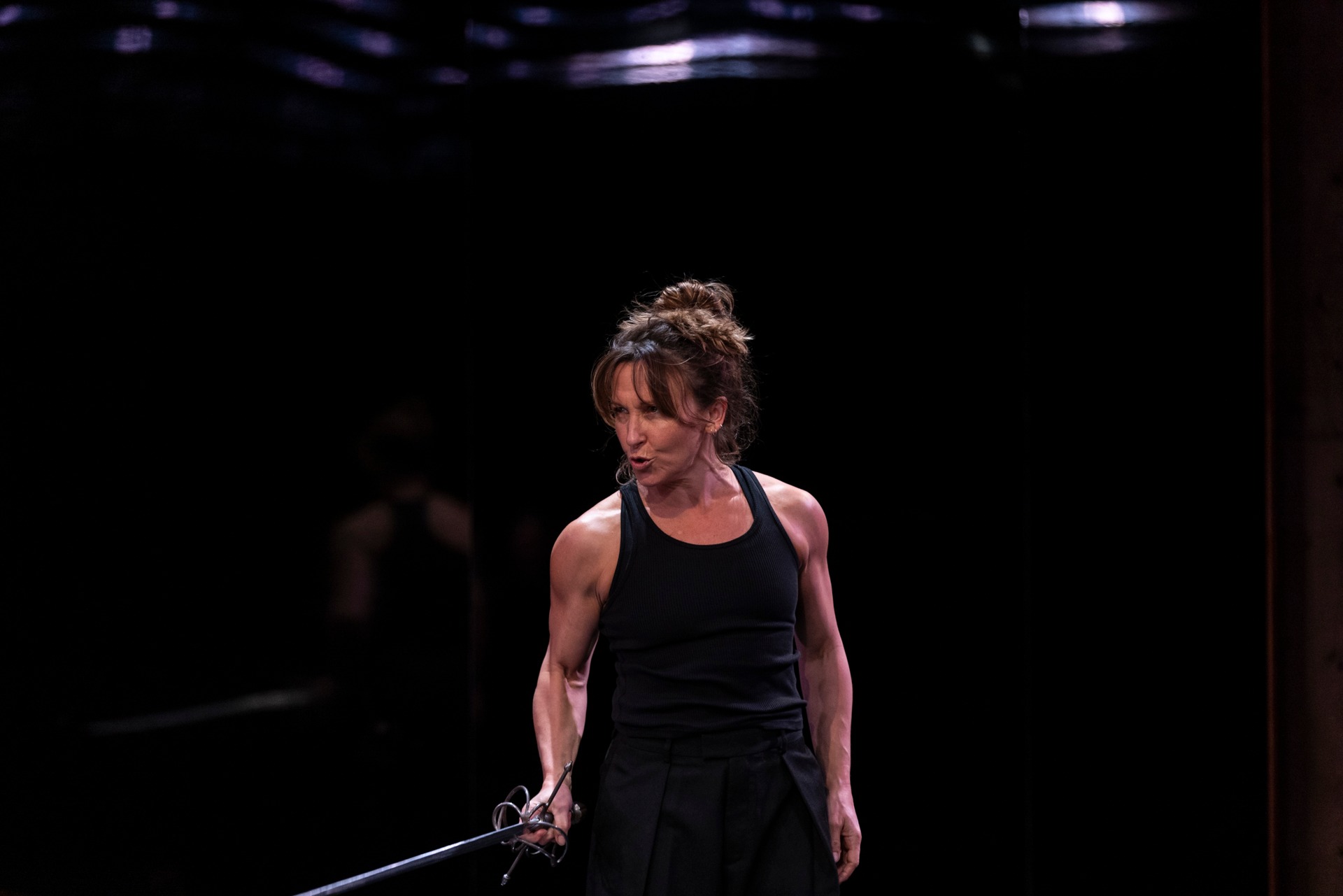

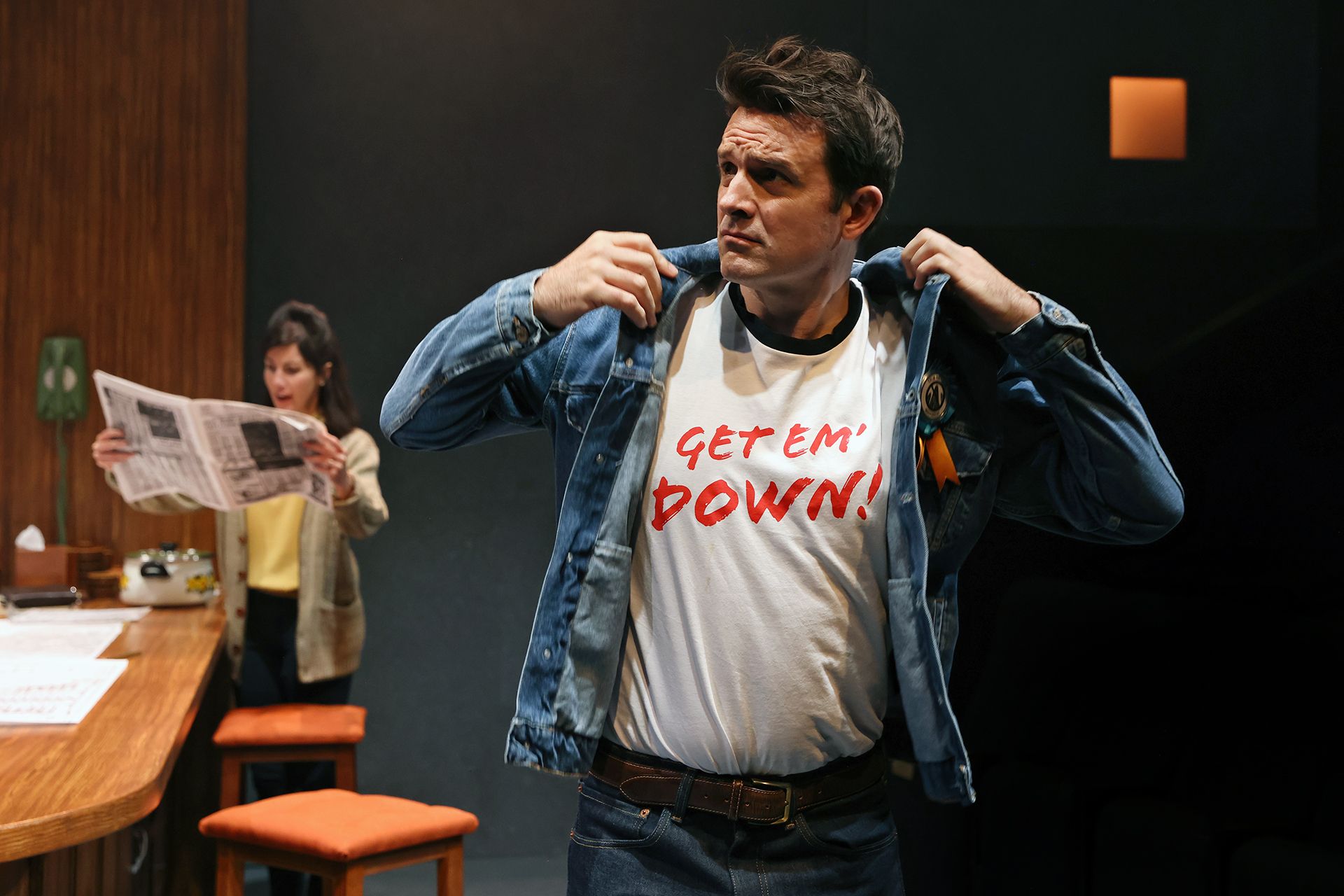

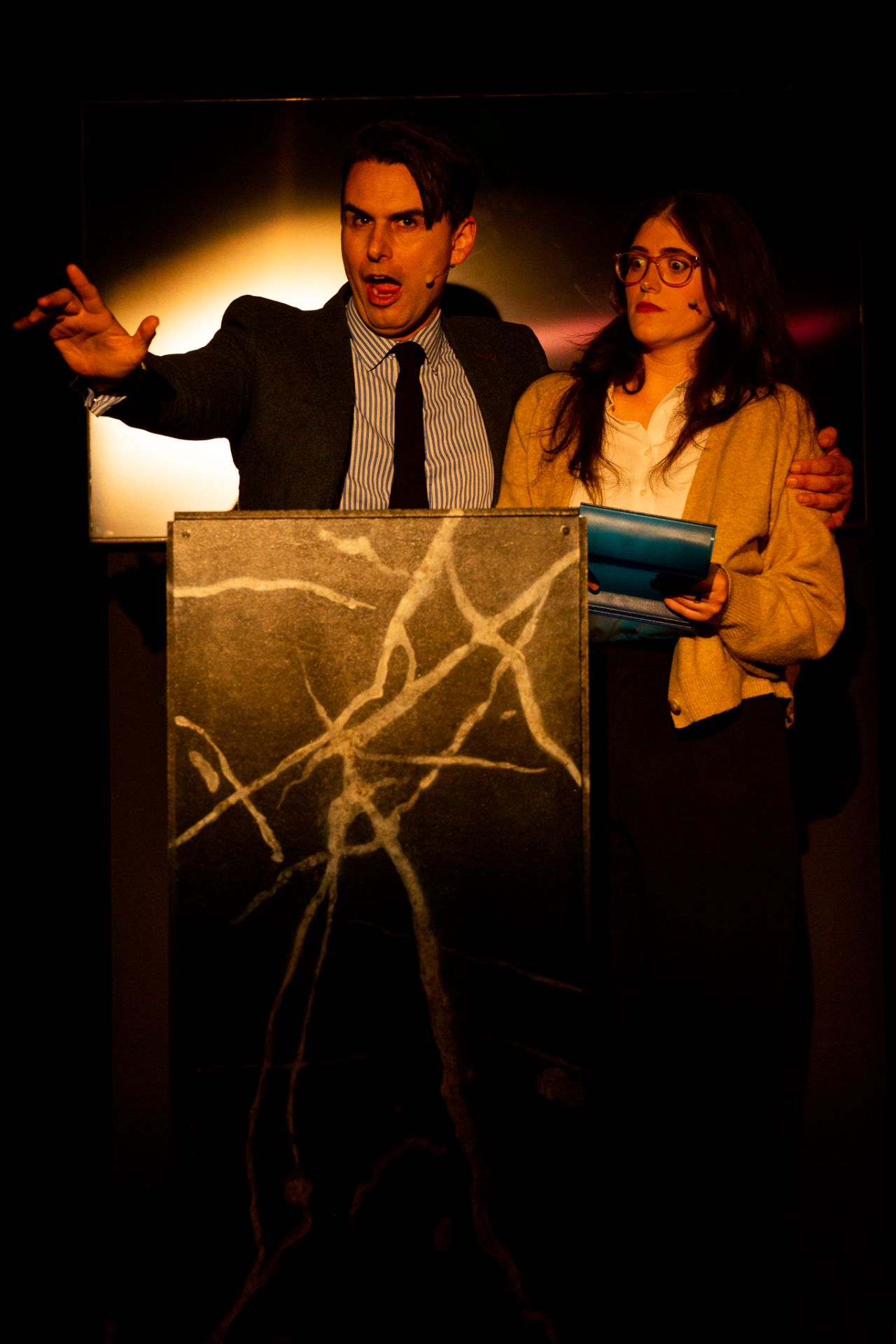

Cast: Fraser Crane, Ryan Hodson, Mym Kwa, Oli McGavock, Lou McInnes, Dominique Purdue, Connor Reilly, Rachel Seeto, Kate Wilkins, Angharad Wise

Images by Phil Erbacher

Theatre review

It is always between classes, when we see the young people of Jacob Parker’s Dumb Kids chatting and socialising. There is occasional talk about their impending Year Eleven Social, but these ten teenagers are mostly occupied with matters of a sexual nature. At their age especially, talking about sex is really an exploration of self identity, and in Dumb Kids we see a fascinating microcosm, representative of the state of youth culture in 2023. Australia in the future, it may seem, is no longer predominantly straight, with lesbians, gay men, bisexuals and pansexuals becoming as commonplace as heterosexuals. Trans and nonbinary people too, are no longer anomalies in how we recognise gender experiences. Queer, it may seem, is everything.

Parker’s depictions can of course be considered an exaggeration, not only of queerness, but also of a particular kindness that has hitherto eluded most stories pertaining to this cohort. Masculinity is very present in Dumb Kids but its toxic aspects have largely disappeared. Bullying and intimidation are no longer a significant driving force, in this narrative about adolescent sociality. Conformity too has subsided, with these teenagers completely at ease with notions of diversity. Angst and confusion however remain essential, for it is wholly natural to see humans never figuring everything out, about our very own existence, even after learning that we can all make different choices in self-determination.

The bold and idealistic writing is brought to life by Sophia Bryant, whose direction is memorable for imbuing a valuable authenticity, that makes the audience receptive to these radically new portrayals of our young. Along with movement choreography by Emma Van Veen, the show is visually appealing, commendable for delivering much more than configurations of bodies in naturalistic conversational postures.

Set design by Benedict Janeczko-Taylor offers a theatrical rendition of the school playground, charming with its use of colour, and clever in its creation of spatial potential for performers. Janeczko-Taylor’s delightful work extends to costumes, with intricate details that make this staging feel simultaneously real and elevated. Thomas Doyle’s lights reveal an adventurous spirit, choosing to deliver fantastical imagery rather than something more lifelike, and therefore impressive for its ambitious artistry. Music by Christine Pan keeps us in tune with the frequencies of this generation, giving definition to how the staging wishes to conceive of the here and now.

An ensemble of ten effervescent performers bring wonderful spirit and dedication to Dumb Kids, exceptional with the cohesion they have fostered so successfully. Every character is believable and likeable, in a play that resists taking sides. There is no us and them, no good people or bad people, just humans navigating one day at a time. The generosity embodied by the cast, allows for a certain utopic vision to make sense, so that we can begin to be convinced of a brighter future. When all the world turns queer, is when no group is allowed to dominate, and when no one is left outside.